Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

As the Chinese Communist Party convenes next week to embellish and extend Xi Jinping’s role as emperor, the mandate of heaven wobbles.

The imperial mandate has been translated into a Marxist mandate of history. Heaven or history, the mandate confers legitimacy based on performance.

One CCP gauge for the state of the mandate is ‘comprehensive national power’, measuring a country’s economic, military and political weight. The national power calculation draws on the Soviet concept of the correlation of world forces and Karl Marx’s observation: ‘Merely quantitative differences, beyond a certain point, pass into qualitative changes.’

For much of Xi’s decade, the quantities have stacked up favourably and the quality of China’s power surged. The comprehensive power needle leant China’s way, pointing to significant gains against other states.

Suddenly, though, the power needle has stuttered. At the very least, the relative growth of Chinese power has slowed. And whisper it quietly as the emperor steps higher: some slippage is apparent.

The tide turns against China’s helmsman, domestically and internationally.

One bad period doesn’t negate all China has achieved since Xi took office in 2012, yet the power meter blips. This is not the 2022 that Xi ordered—a masterfully staged Beijing Olympics was supposed to be followed by a calm, ordered progress to the 20th National Party Congress.

The CCP gathers to bury the collective leadership model and remove all checks on Xi as China staggers on through Covid-19 lockdowns. Consider the irony, Kerry Brown comments, if a public health issue caused the people to question Xi’s mandate: ‘Zero-Covid is having an impact across the nation. A government that places ideology and political commitment above everything—even the public wellbeing and economic prosperity that lies at the heart of their legitimacy—runs risks like never before.’

Runs risks? That’s far from the calmly confident congress Xi wants.

Beijing set a GDP target of 5.5% for this year, but is on course for its biggest ever GDP miss. The actual percentage figure to be delivered will start with a 4 or even a 3. The days of double-digit growth fade to history. The middle-income trap is snapping. The debt mountain has become what Reuters calls ‘a threat to China’s stability and even the world’s economic health’. The real estate crash is ‘a slow motion financial crisis’, revealing systemic problems. The demographic reckoning looms as China’s population ages faster than that of any other country in modern history.

China exults that it’s the world’s largest exporter and official creditor, but frets at the might of the US dollar, still the most important currency, pre-eminent in trade and cross-border debt.

Unable to knock the greenback from its peak, Beijing seeks to build a digital payments system instead. The digital currency is ‘programable’, allowing China to impose conditions, giving a ‘god’s eye view of the currency’ and how it’s used. See ASPI’s 2020 report on the international implications of the digital version of the yuan.

Putting much of this together, Sebastian Mallaby has penned an op-ed pointing to the emerging cracks in the system, starting with these opposed questions: ‘Is China (a) an economic juggernaut, rapidly overtaking the United States in the technologies of tomorrow? Or is it (b) an ailing giant, doomed by demography, failing real estate developers and counterproductive government diktat?’

The CCP will embrace option (a) because Xi—princeling turned emperor—is both product and expression of the party.

China’s strategic equation has shifted dramatically since 4 February, when Xi and Russia’s Vladimir Putin announced their ‘no limits’ pact, pledging ‘no “forbidden” areas of cooperation’. Ukraine has turned this into a limited liability deal, with much off limits.

China stays on the safe side of the sanctions against Russia, offering supporting words but no weapons. When the two leaders met again last month, Putin acknowledged Xi’s ‘questions and concerns’. Whatever the cracks in the marriage of convenience, Xi is bound to his fellow autocrat in a dangerous world.

Beijing’s judgement of the military balance suddenly involves a huge Russia discount. On the other side of the calculation sits the new 50-nation Ukraine Defense Contact Group, offering what the US describes as momentum and resolve.

China’s military budget has grown for 27 consecutive years and it’s comfortably settled as the world’s second largest, while still well short of half what the US spends. Broaden beyond the bilateral comparison, though, and the power computation becomes problematic.

China’s growing assertiveness is a major driver of military spending by countries such as Australia and Japan (the 7.3% jump in Japan’s defence budget last year was the biggest annual increase in 50 years).

The total defence spending of the Quad (Australia, India, Japan and the US) is triple that of China. No question about the prime driver for the Quad getting back together in 2017: a disruptive Xi is the group’s godfather.

The self-obsession of the CCP means it pays close attention to parties and political players elsewhere. Beijing will have noted the alliance of parliamentarians from almost 30 countries drawing up a blueprint last month to help democracies resist Chinese intimidation. The Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China aims to safeguard the international rules-based order, uphold human rights, promote trade fairness, strengthen security and protect national integrity.

From values to vital defence kit, there’s a lot of pushback happening.

No clear answer is possible in the debate about whether we’re approaching ‘peak China’. Indeed, a slowing or weakening China might be more dangerous than a nation confident that time is on its side.

The spectre haunting the CCP congress is that the international tide has turned, while the domestic waters are choppy.

The clear judgement is that the relative increase in China’s power is slowing.

The needle on the power meter is wavering, and it might just be waning.

Geography influences the strategic choices of all countries, but Vietnam is an interesting case of a ‘swing’ state in comparative grand-strategy terms. The country occupies the eastern part of the Indochinese Peninsula, with an elongated coastline of 3,260 kilometres facing the South China Sea. Vietnam also sits unambiguously in continental Asia, sharing a 1,300-kilometre border with China, as well as abutting Cambodia and Laos. This duality in Vietnam’s situation, straddling Southeast Asia’s geostrategic fault line, gives it unusual flexibility to develop a continental or maritime orientation. Despite a strong landwards pull in Vietnam’s history, Hanoi has latterly and perhaps decisively adopted a maritime course, though the country’s grand strategy remains dynamic and is actively debated among observers.

In the second half of the 20th century, Vietnam’s communist leadership was absorbed by the anti-colonial struggle and national unification. The long wars against France and then the United States, when Hanoi’s ideological and material allies were the Soviet Union and China (to a lesser extent), encouraged a continental disposition. Coastal supply routes were important to sustaining Hanoi’s revolutionary war effort in South Vietnam, but the main axis of supply ran overland through Laos and Cambodia, along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. North Vietnam’s armed forces lacked the means to contest US sea control in the South China Sea. China forcibly expelled South Vietnamese forces from the Paracel Islands in 1974, though Hanoi maintains Saigon’s claim. After reunification in 1975, Vietnam’s border conflict with China in 1979 and prolonged military intervention in Cambodia throughout the 1980s ensured that Hanoi was preoccupied by land-based threats for the remainder of the Cold War, with the exception of a brief clash with China in the Spratly Islands in 1988.

In the 21st century, however, Vietnam has transformed into an export-oriented economy that depends upon freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, and beyond, to deliver its prosperity. This has influenced its threat perceptions. The majority of Vietnam’s population and infrastructure is concentrated on the coast, making it vulnerable to attack from the sea. Vietnam has to defend and police the oil, gas and fish within its exclusive economic zone, as well as its territorial claims in the Spratly Islands. If, in future, China is able to exert uncontested control within the so-called nine-dash line, and acquires access to a naval base in Cambodia, Vietnam could find itself encircled and vulnerable to blockade. Once access to seaborne trade is denied, Vietnam would suffer immediately and grievously.

The move towards a maritime strategy is evidenced by changes to Vietnam’s defence capability. Despite the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis, Vietnam doubled its defence expenditure between 2006 and 2010. From 2009, it began acquiring six Russian Kilo-class submarines armed with anti-ship and land-attack Klub supersonic cruise missiles capable of hitting China. The modernisation of the Vietnam People’s Navy was officially declared a priority at the 11th National Party Congress, in 2011. The 2019 defence white paper put a seal on Vietnam’s strategic reorientation by officially identifying it as a maritime nation. Vietnam is unlikely to prevail in a serious maritime conflict with China, but it has made significant investments to raise the costs of aggression.

Despite these trends, it has been argued recently that Vietnam should ‘look west for its survival’ and refocus its strategic attention from the maritime domain to its land borders because ‘the balance of power on land works more in Vietnam’s favour’. According to this line of argument, Hanoi has little long-term hope of defending its maritime claims in the South China Sea due to the growing power disparity between China and Vietnam.

But the strategic situation on land is less severe than it may first appear. In reality, a binary continental-versus-maritime dilemma is somewhat artificial; Vietnam will continue to look landwards for its security, and to some extent for its prosperity too. Hanoi cannot overlook the possibility of invasion or incursion across its land borders. It is also the case that Vietnam’s armed forces remain army dominated for historical reasons. However, China and Vietnam signed a border treaty in December 1999, which was ratified in 2000. The two sides completed border demarcation in 2009. Although China has a dominant economic profile and significant political influence in both Cambodia and Laos, Vietnam’s Southeast Asian neighbours remain sovereign states and are unlikely to allow the People’s Liberation Army to launch attacks on Vietnam from their territory. Even if Phnom Penh and Vientiane agreed to host PLA ground and air forces, invading Vietnam would be prohibitively expensive, as demonstrated by Russia’s war in Ukraine and, indeed, China’s costly invasion of northern Vietnam 43 years ago.

By contrast, China’s unilateral and expansionist actions in the South China Sea haven’t faced serious consequences. Since 2009, Beijing has incrementally ramped up its claims across the South China Sea, consolidated its control in contested areas, interfered with the sovereign economic activities of other claimants within their exclusive economic zones, and militarised those features it has converted from rocks and reefs into artificial islands. China can exert pressure on Vietnam from the sea at much less risk to itself than over land, including but not limited to the use of grey-zone tactics.

If Vietnam were to vacate the features that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, China would be certain to fill the resulting vacuum, further strengthening its control. Giving up on the South China Sea would be widely unpopular with the Vietnamese public, potentially threatening the legitimacy of the Vietnamese Communist Party. Most importantly, accommodating Beijing’s maritime expansionism as a fait accompli would undermine Vietnam’s long-term security and that of the surrounding region. Hanoi has progressively aligned its domestic legislation with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and international law because its long-term interests are best served by upholding the rule of law and peaceful dispute resolution.

Vietnam’s maritime strategic orientation has fostered closer economic and security partnerships with Australia, India, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States. As Vietnam attracts more foreign investment, including production relocated from China, it has become important to international supply chains, giving other countries an increased stake in its security. External assistance has significantly improved Vietnam’s maritime law enforcement capacity, enabling it to develop its marine economy despite continuous pressure from China in the South China Sea.

Any reversal of the prevailing maritime strategy is therefore unlikely to hold water with Hanoi’s key decision-makers, who have embraced a maritime orientation as essential to Vietnam’s national security.

Vast and, more often than not, hidden supply and value chains underpin modern Australian life. We’ve become accustomed to, if not overly confident in, the ability of markets to meet our every need and want. Covid-19 and a series of concurrent natural disasters have left us with a nagging feeling that things might not really be so rosy. It’s become painfully apparent that some countries won’t always act in the interest of open global trade.

Addressing this challenge requires some big, new policy thinking. Global magnesium supply chains illustrate how difficult that will be.

The supply and value chains for magnesium are a long way from the minds of average Australians. Many would assume that because Australia is a bulk mineral ore exporter without a significant manufacturing base, there’s no need for magnesium to be a concern. That assumption is wrong.

Magnesium is a critical input for major and emerging economies’ economic and industrial development. It has diverse high-tech applications in a wide range of sectors, from renewable energy to aerospace, defence to transport, and telecommunications to agriculture. The global demand for aluminium alloys, made from magnesium, is increasing. Magnesium is critical to the growing market for electric vehicles since its light weight helps to increase their range.

However, for industry and sometimes governments, magnesium supply chains are vulnerable to sudden disruptions.

By 2019, China had become the dominant producer of magnesium, capturing a 94% share of the global export market. Its companies produce magnesium at prices that no other market can match.

Chinese companies have avoided the temptation of using market share to set high prices. Instead, they have set prices that present competitors with high barriers to market entry. The low prices have been a windfall for both manufacturers and consumers, and have helped further entrench China’s market dominance.

Interestingly, our understanding of the supply-chain vulnerabilities created by this arrangement wasn’t driven by increasing strategic uncertainty but by Chinese domestic policy.

As early as 2006, the Chinese government had become concerned about energy security in light of China’s growing economy. In 2016, it introduced a dual-control policy focused on reducing energy intensity and limiting overall consumption. However, the policy wasn’t afforded any real priority, so it had a limited impact.

About a year ago, the central government began actively monitoring consumption across China. In September 2021, Shaanxi Province fell victim to the country’s ‘double control’ when it failed to meet energy consumption targets. The government swiftly shut down high-energy-intensity industries, including aluminium production. An international supply crisis ensued, and prices have soared.

Of course, higher prices could make entering the market more attractive to new players. But establishing magnesium value chains—from mines to producing unwrought magnesium and aluminium—takes time. Then there’s the added complexity of climate and trade policies. Plus, investors know that the supply chain shortages relate to Chinese domestic policy, which could be reversed just as quickly to prevent market entry.

Canada, the EU, Japan, the UK and the US are all reeling from the sudden disruption of the magnesium and aluminium supply chain. All are trying to find a way to address the issue and reduce prices to avoid further disruption in manufacturing. While markets are part of the solution, they alone won’t resolve this problem. Like Australia, most of these countries have limited experience in intervening in markets of this type. A resilient global supply chain will require work from each nation, both individually and in cooperation with one another. Resilience will have a price premium attached to it. Still, this latest episode shows that inaction has a price too.

Australia is an established magnesium producer. Companies like Magneto Metals, with its Batchelor magnesite project in the Northern Territory, are poised to provide supply-chain resilience. Like other companies, Magneto Metals knows that ‘to succeed, projects will need to have an integrated low-cost, low-carbon energy strategy and carbon footprint, meet increasingly stringent ESG [environmental, social and governance] policies and a competitive operating cost’.

But unlike similar projects in China, Australian companies face additional costs for infrastructure development, such as roads and affordable power supplies. In the Northern Territory, the future of magnesium rides on investments in facilities like Darwin Harbour’s Middle Arm Sustainable Development Precinct. China’s market domination still allows it to manipulate pricing, however, and Chinese state-controlled companies have arguably used their market dominance to affect commodity prices in the past in order to inhibit the growth of competitors in the market for rare-earth elements.

A small grouping of like-minded countries could ensure carbon pricing along these supply chains. Such an approach would reward companies that adopt less emissions-intensive processes, resulting in greater competition among suppliers.

Globalisation in one form or another is no doubt here to stay, but the age of predictable, reliable supply chains is over.

The Chinese Communist Party is attempting to influence public discourse in Solomon Islands through coordinated information operations that spread false narratives and suppress information contradictory to the party’s message.

Since November 2021 when anti-Beijing riots broke out in the Solomons capital of Honiara, the CCP has used its media and disinformation capabilities to shape public perception in Solomon Islands of security issues and foreign partners. These messages—in alignment with the CCP’s regional objectives—have a strong focus on undermining the Solomons’ existing partnerships, namely with Australia and the US.

In the immediate aftermath of the Honiara riots, the CCP sought to blame Australia, the US and Taiwan for instigating the unrest. In the weeks that followed, CCP officials were also active in pushing a narrative that ‘foreign forces with ulterior motives’ were aiming to smear the relationship between Solomon Islands and China.

After the China – Solomon Islands security agreement was leaked in late March, the CCP pushed a narrative that Australia and the US were interfering in the Solomons’ affairs; were ‘colonialist’, ‘threatening’ and ‘bullying’; and had no genuine interest in supporting the country’s development. Although this narrative wasn’t exclusively used after the security agreement was leaked, the frequency of these accusations in Chinese party-state media and official statements increased dramatically.

Some of the CCP’s messaging occurs through routine diplomatic engagement, but there’s also a coordinated effort to influence the population by amplifying the messages of particular individuals and pro-CCP content across a broad spectrum of information channels. That spectrum includes party-state media, CCP official–led publications and statements in local and social media, and official party-state Facebook groups.

There’s now growing evidence to suggest that CCP officials are actively attempting to suppress information that doesn’t align with the party-state’s narratives across the Pacific islands through the coercion of local journalists and media institutions as part of the CCP’s larger information operations.

A new ASPI report, released today, examines the level of activity and effectiveness of each of these channels of influence in the Solomon Islands information environment. This includes quantitatively measuring the degree of online penetration in social media, the level of engagement generated through online commentary, and the effectiveness in swaying public attitudes through sentiment analysis of Facebook commentary.

In doing so, we have established a baseline understanding of the CCP’s activities and influence in Solomon Islands. This aids in identifying the channels of influence that are of most concern and also enables us to detect and warn against shifts in activity levels or effectiveness across channels of influence over time.

The results varied greatly across the channels of influence. Party-state media, although useful for identifying narratives pushed by the CCP, had little impact on and penetration into the Solomon Islands online information environment. These articles, produced at a rate of one every two days, were rarely shared online and received mostly negative responses about China. Likewise, Chinese embassy Facebook posts were also limited in their penetration and engagement.

The influence channel of most concern, identified as being the most effective in propagating CCP narratives online, was the publication of CCP official–led articles in local media. This included opinion pieces, press releases and locally produced articles that were almost entirely dependent on direct quotes from CCP officials. These publications came wrapped in the packaging of a trusted local media source and allowed the CCP to spread its message to a wider audience, resulting in greater penetration and engagement. The CCP was highly active in this area. In this case of the Honiara riots, CCP officials had almost as many statements published in local media discussing the cause of the riots as the Solomon Islands own government officials.

Our sentiment analysis of Facebook comments on these shared articles showed that the Solomon Islands online population was mostly negative towards Chinese influence and engagement. But, in the case studies examined, there was a trend of declining anti-China sentiment followed by an increase in either pro-China or anti-Western commentary. These changes in sentiment, although highly variable week-to-week, correlated with real-world attempts to influence the population—such as a message from China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, or a media statement criticising the United States’ announced visit to Solomon Islands. The language used by the CCP is also repeated in the commentary by Solomon Islanders.

This report is only the beginning of our attempt to understand the size and effectiveness of CCP information operations and influence in the Pacific. The CCP’s information operations in Solomon Islands are part of a broader effort to control the narrative and sway public opinion across the region, and further investigation into malign actors and activities impacting the Pacific islands’ information environment is needed. Support from the Australian government and international partners will be vital to improving understanding of the information environment in order to better combat misinformation, disinformation and propaganda.

The Australian government also needs to do more to coordinate with other foreign partners of Solomon Islands, including the US, New Zealand, Japan and the EU, to further assist local Pacific media outlets in hiring, training and retaining high-quality, professional journalists. A strong, more resilient media industry in Solomon Islands will be less vulnerable to disinformation and the pressures that may be exerted on it by local CCP officials.

Russian President Vladimir Putin sought this month to contrast the vibrant economies of Asia with the decadence of the West, signalling that Russia’s future lay with the East.

The economic and political dominance of the United States was waning, he told an economic forum in Vladivostok, and the Western elites were blind to the ‘irreversible, or should I say tectonic shifts’ in international relations as emerging nations, led by the Asia–Pacific, played a much bigger role.

‘Asia–Pacific countries emerged as new centres of economic and technological growth, attracting human resources, capital and manufacturing.’

He cited International Monetary Fund estimates showing that Asia’s share of the world economy would rise from the 37% it held in 2015 to 47% by 2027.

He contrasted the Asia–Pacific’s average growth over the past decade of 5% with the United States’ growth of 2% and the European Union’s 1.2%.

He didn’t mention Russia’s average growth of 0.9% over that period, or the IMF’s forecast that the country’s share of the global economy will shrink from a high of 3.5% in 2013 to 2.3% by 2027.

While Russia straddles both the east and the west of the Eurasian landmass, 80% of its population and nearly all its manufacturing lie west of the Urals in the European zone.

Figures from 2020 show that Europe accounted for 50% of Russia’s imports and 50% of its exports, while the Asian share was 42% for trade in both directions. Collectively, those sanctioning Russia, including the EU, the US, Japan and South Korea, account for 60% of Russia’s pre-war trade.

Russia’s ‘forever friend’ in China, by contrast, accounted for about 15% of Russia’s exports and 23% of its imports.

Putin is right to point to the dynamism of Asian economies, particularly China and the ASEAN group; however, much of the growth in prosperity in the region has been generated by its integration into Western-controlled supply chains and is aimed at satisfying Western markets. Foreign affiliates accounted for more than a third of China’s exports in 2021, and the share is likely higher across the ASEAN nations. The West, particularly the US, remains the principal driver of transformative technological innovation.

It will take time to see how Russia’s trade evolves, but it has permanently damaged its most important markets. Europe and especially Germany will not again allow themselves to become dependent on Russia for energy and vulnerable to Russian economic sabotage.

Although Russia has reaped profits from soaring oil, gas and coal prices, the volume of its fossil fuel sales is down about 20%, with further falls in prospect as the EU imposes new sanctions.

OPEC provides an object lesson on the perils of using the supply of a commodity for geopolitical advantage.

On the eve of the 1973 embargo, the OPEC nations were producing 1,500 million tonnes of oil a year while the rest of the world’s output was 1,400 million tonnes. Within a decade, OPEC annual production had dropped to 850 million tonnes while the rest of the world’s output had soared to 2,000 million tonnes.

Russia’s oil and gas industry will not recover. Many of Russia’s most important fields have declining production and were looking at partnerships with major Western oil companies and service providers to introduce new technologies for lateral drilling to extend their lives. Those partnerships have now dissolved. Western technology would also be crucial for the construction of LNG plants capable of turning a meaningful share of the gas Russia used to pipe to Europe into liquids that could be shipped to global markets.

Although Russia already pipes gas to China and has another pipeline under construction, its capacity is only a small share of the gas it used to send to Europe.

Sanction regimes are never watertight, particularly for commodities that account for about two-thirds of Russia’s exports. Russia will continue to earn export revenue. However, the loss of access to Western technology will hobble the development of Russia’s more advanced industries over the medium term.

Putin declared that Russia was ‘coping well with the economic, financial and technological aggression of the West’, although he conceded that ‘sectors, regions and enterprises’ that depended on Europe either for supplies or as a market were facing some problems.

He described Western sanctions as an ‘aggressive attempt to impose models of behaviour on other countries, to deprive them of their sovereignty and subordinate them to their will’.

There have been claims that Western sanctions have met with little success as life goes on as usual in Moscow apart from a few Western shops having shut.

But Russia’s own public statistics show that the sanctions are cutting deep in some sectors. Motor vehicle production in the first half of the year was down 62%, while production of fridges was down 40% and washing machines 35%. Production of electric motors was down 36%, while fibre cables were down by 33%.

Most of the sectors with big falls are technology intensive, although there have been drops of at least 15% in the manufacture of an array of goods including cigarettes, knitted fabrics and plywood, which presumably reflect the difficulty of importing basic materials because of financial sanctions.

Russian airlines have been affected because of difficulties in maintenance. Domestic air travel was down 83% and air freight was down 70%.

Putin railed against the financial sanctions, saying that Russia was taking steps to reduce its reliance on ‘unreliable and compromised foreign currencies’. China has now agreed to settle its gas purchases from Russia half in yuan and half in roubles.

‘In an attempt to resist the course of history, Western countries are undermining the key pillars of the world economic system built over centuries. It is in front of our eyes that the dollar, euro and pound sterling have lost trust as currencies suitable for performing transactions, storing reserves and denominating assets,’ he said.

In reality, the value of the US dollar is soaring, and it remains on one side of around 90% of all international transactions. Its dominant role reflects the depth of its liquidity (transactions of any size can be completed without affecting the exchange rate) and the size of US capital markets. While Russia and China can settle their trade in whatever currency they wish, global businesses want to use US dollars to intermediate trade.

The combined force of sanctions, capital flight and export controls have not consigned Russia to ‘economic oblivion’, as claimed in a recent and overstated paper from academics at Yale University, but they will have a significant and long-lasting impact on Russian standards of living that no pivot to Asia can overcome.

There was a time when well-meaning, if not wishful-thinking, Westerners thought that ‘China’s Gorbachev’ was the highest compliment they could pay a Chinese leader who looked like a reformer. But when Zhu Rongji, the straight-talking mayor of Shanghai, visited the US in July 1990, and some Americans called him that, the future premier was not amused. ‘I am not China’s Gorbachev’, Zhu reportedly snapped. ‘I am China’s Zhu Rongji.’

We will never know what Zhu, widely admired for implementing key reforms in the 1990s and spearheading China’s successful efforts to join the World Trade Organization, really thought about Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, who died on 30 August. What we do know for certain is that, in the eyes of most leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, Gorbachev committed the unforgivable crime of causing the collapse of the Soviet Union.

At the most practical level, the CCP’s vilification of Gorbachev makes little sense. Sino-Soviet relations improved dramatically during his six-year reign. The collapse of the Soviet Union was also a geopolitical boon to China. The lethal threat from the north nearly disappeared overnight, while Central Asia, formerly part of the Soviet space, suddenly opened up, enabling China to project its power there. Most importantly, the end of the Cold War, for which Gorbachev deserves much credit, ushered in three decades of globalisation that made China’s economic rise possible.

The only plausible explanation for the CCP’s antipathy towards the former Soviet leader is its fear that what Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika accomplished in the former Soviet Union—the dissolution of a once-mighty one-party regime—might also happen in China. Chinese rulers do not share Russian President Vladimir Putin’s view that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a ‘major geopolitical catastrophe’ of the 20th century. To them, the fall of the USSR was a major ideological catastrophe that cast a shadow over their own future.

Evidence of the CCP’s lasting vicarious trauma is readily visible even today—more than three decades after Gorbachev sealed the fate of the Soviet empire. In late February, the party’s propagandists began to screen Historical Nihilism and the Dissolution of the Soviet Union, a 101-minute documentary that blamed the Soviet Communist Party for failing to enforce strict censorship, particularly regarding history and Western liberal ideas.

Still, the CCP’s obsession with the Soviet collapse seems odd, given the party’s three decades of undeniable success at avoiding a similar fate. The CCP’s most obvious achievement was to gain legitimacy by delivering ever-rising standards of living. It was no coincidence that less than two months after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 87-year-old Deng Xiaoping rallied a demoralised party to restart stalled reforms and prioritise economic development over everything else.

Another less well-known, but no less important, success was the CCP’s effort to prevent a Gorbachev-like reformer from rising to the top and dismantling its rule from within. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the party took extreme care in vetting its future leaders. Only officials whose political loyalty was unimpeachable would be entrusted with power.

The party also scored an unexpected propaganda coup when much of the former Soviet Union descended into chaos and economic crisis in the 1990s. By playing up the suffering of ordinary Russians, the party crafted a persuasive message to the Chinese people: putting the economy ahead of democracy is the right path.

Yet, despite the CCP’s impressive achievements in the decades since the fall of the Soviet Union, it is still haunted by the legacy of Gorbachev. Some may argue that, as in all dictatorships, the party’s insecurity and paranoia have no cure. But China’s rulers have been determined to prove otherwise.

In the 1990s, the CCP’s top leadership commissioned a series of academic studies exploring the causes of the Soviet collapse. Participants in this intellectual effort included both well-respected scholars and party hacks. While they could agree on many less controversial factors, such as poor economic management, an unwinnable arms race with the United States, imperial overreach and ethno-nationalism in non-Russian republics, they argued fiercely over the role of Gorbachev.

The party hacks insisted that Gorbachev was primarily responsible for the Soviet collapse, because his ill-conceived reforms weakened the communist party’s grip on power. But scholars with genuine expertise regarding the Soviet Union countered that the fault rested with Gorbachev’s predecessors, particularly Leonid Brezhnev, who ruled the empire from 1964 to 1982. The political stagnation and economic malaise of the Brezhnev era left behind a regime too rotten to be reformed.

Today, judging by China’s official narrative of the Soviet collapse and enduring hostility towards Gorbachev, it’s obvious that the party hacks won the debate. But it is doubtful that China’s leaders have learned the right lesson from history.

The Chinese government’s aggression towards Taiwan has highlighted the range of powers and tools it wields. Alongside its show of military force, China has restricted trade with Taiwan, sought to promote its narrative on China–Taiwan–US relations, arrested at least one Taiwanese citizen, carried out cyberattacks against Taiwanese entities and cancelled engagements with the governments of the United States and Japan.

Many commentators have talked about these tools using familiar ideas like hybrid threats, grey-zone operations and information operations. But those concepts can be counterproductive unless policy and analysis are grounded in the ideas and structures that actually guide and organise them in Beijing. Understanding Beijing’s frameworks shows how much remains to be learned about how its external influence is interwoven with China’s international engagement. A failure to get on top of this will position policymakers to misinterpret and overlook key parts of China’s power and influence.

The recent history of awareness and research on the Chinese Communist Party’s external influence work shows why getting our concepts right is important. For years, China scholars such as Anne-Marie Brady, Feng Chongyi, John Fitzgerald, John Garnaut and Peter Mattis raised the alarm on the party’s efforts to influence, control and interfere in Chinese communities around the world. Much of this activity falls under the scope of the party’s ‘united front work’, the work of agencies seeking to co-opt and influence ‘representative figures’ and groups inside and outside China, with a particular focus on religious, ethnic minority and diaspora communities.

The tendency to try to fit this phenomenon under the umbrella of Western concepts of public diplomacy and soft power is part of what held governments back from understanding and responding to challenges posed by China’s united front work. Until recently, problems in diaspora communities seemed either trivial or unimportant to many governments, which only recently recognised how united front work harms social cohesion, undermines civil liberties and facilitates covert and clandestine operations.

United front work was misunderstood because it was often viewed as a form of public diplomacy, which is acceptable and practised by all governments. While united front work has superficial similarities to public diplomacy—it includes holding cultural events and open outreach to Chinese communities—its objectives, scope and covert aspects make it fundamentally different. For example, MI5 warned in January this year of an individual ‘seeking to covertly interfere in UK politics’ on behalf of the United Front Work Department.

‘United front work’ is now a household name, at least inside the world’s foreign-policy bubbles. An understanding of united front work was a key foundation for the initial Australian government response to foreign political interference. You can also find the term in records of parliamentary debates and even legislation. In February 2020, then US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo revealed that his time as CIA director taught him that the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries was ‘the public face of the Chinese Communist Party’s official foreign influence agency, the United Front Work Department’.

While united front work is no longer ignored, the convenience of simplifying diverse kinds of external influence work to accord with our familiar concepts has continued. This has distorted how united front work is understood. As the prominence of united front work as a concept has grown, some scholars, commentators and policymakers have gone too far in treating it as a synonym for foreign interference or influence. Pompeo’s speech was one example of this—the friendship association he named has little to do with the United Front Work Department— but his formulation was only symptomatic of the way such issues have been framed by experts.

Part of this confusion comes from the many meanings of united front work. In one sense, the term refers to a tradition of influence work from the Chinese Civil War, focused on co-opting influential figures who can work in alignment with the CCP’s interests. This tradition is relevant to much of the CCP’s influence work.

But if we’re interested in understanding the different structures, goals and methods of CCP external influence today, then a narrower definition might be more useful. When party officials and state media refer to ‘united front work’ now, they are generally talking about activities guided by top-level coordinating bodies for, and recently codified party regulations on, united front work. In contrast, while the CCP’s International Liaison Department was once part of the United Front Work Department, the 70 years since its founding have seen it develop such that its methods deserve study in their own right, as distinct from united front work.

Though united front work frequently involves foreign interference, equating the two can obscure the uniquely troubling features of united front work, as well as the importance of all the party’s other forms of external influence. Activities we might label as grey-zone tactics, malign influence or information operations cover several distinct kinds of work and bureaucratic systems that permeate China’s engagement with the outside world.

At the highest levels of the party-state bureaucracy, work is assigned to overlapping interagency ‘systems’ organised along functional lines. The united front work system is particularly important, but the work of China’s foreign affairs, propaganda, military and civilian security systems can also intersect with Western definitions of foreign interference.

External influence is a core part of their work, and understanding this helped Australia formulate its strategy to counter foreign interference. For example, Czech counterintelligence service BIS assessed in 2015 that China’s International Liaison Department, primarily part of the foreign affairs system, was involved in ‘intelligence activities’. Australian police have accused a Chinese community figure of working with the Ministry of State Security, a civilian security agency, as part of a plan to carry out foreign political interference. The liaison bureau of the People’s Liberation Army’s Political Work Department has sought to cultivate and befriend retired foreign generals, American China scholars and Australian elites.

Understanding the structure of CCP agencies and work systems is anything but an academic issue—it has profound policy implications. Each system and agency has its own traditions, platforms, methods and goals. Responding to and assessing their activities requires an understanding of the purpose, structure and networks of each of them. Lumping various phenomena together as ‘information operations’ or ‘hybrid threats’ is a poor foundation for governments and researchers, especially since governments can use these concepts to guide internal resourcing and funding decisions. It risks drawing attention away from the role of professional intelligence agencies such as the Ministry of State Security. It can gloss over the important ways these influence systems interact with each other, and the weaknesses in the different methods they employ.

It’s certainly not a lack of available material that keeps policymakers from being informed by the party’s own thinking. Many scholars have written about these kinds of external influence activities and how they are organised, although much more research remains to be done.

An extensive library of official Chinese documents and doctrines is available to us, and analysis can help piece together even covert activities. As two scholars from the US Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute wrote earlier this year, what many call China’s ‘grey-zone operations’ has little basis in Chinese military writings. Working through authoritative sources allowed those analysts to explain how China’s concept of ‘peacetime employment of military force’ differs from ‘grey-zone operations’ in substantive ways. They point out that failing to appreciate China’s concept has led to a gap in our attention on a key part of the use-of-force spectrum: events short of a major war such as a Taiwan invasion but more forceful than the deadly June 2020 India–China border confrontation.

While we have PLA publications to help us understand these ideas, my forthcoming book on the Ministry of State Security’s influence operations seeks to demonstrate that careful scholarship also makes it possible to analyse the work and thinking of Chinese intelligence agencies. It also points to the fragmentary and incomplete state of our knowledge of CCP external influence. Arguably, research on China’s intelligence agencies has not advanced substantially in a decade.

Our own frameworks can be valuable for policymakers working on China—to the extent that they’re based on an understanding of the party’s own thinking. They’re important for communicating with the public and governments, especially when they have a legal basis or define the scope of government work. But confusing them for the party’s own guiding ideas introduces a barrier between policymakers and the actual activities they need to understand, a task only more pressing as China seeks to assert its influence on Taiwan and across the Pacific.

Political dynamics in South Asia have been garnering fresh attention this year. In Sri Lanka, a severe economic crisis led to widespread protests in April, followed by the departure of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in early July and a declaration of a state of emergency. Pakistan and Bangladesh have reached out to the International Monetary Fund for loans to help stabilise their depleting foreign exchange reserves.

Indian public discourse on events in Sri Lanka has prompted renewed attention on problematic Chinese loans as a cause of the region’s economic woes, emphasising New Delhi’s potential as the more reliable partner. The broader geopolitical focus on Indo-Pacific cooperative frameworks also pitches India as the dominant power in South Asia.

So, does the current crisis offer a window of opportunity for India to reassert its presence in South Asia? Both the question and the probable answers are complex.

Home to nearly two billion people and some of the world’s most dynamic economies, South Asia is critical to geopolitical considerations in the Indo-Pacific. South Asia’s maritime potential is of increasing importance to larger strategic constructs and has become an area of contestation between small and big powers alike. With the Belt and Road Initiative, China has gradually broadened its relationships in South Asia. But this, along with continuing acrimony on the India–China border, places Beijing in direct contest with New Delhi’s regional aspirations, expressed in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘neighbourhood first’ policy.

Launched with much fanfare in 2014, the policy has faltered, owing to the slow pace of economic projects, among other issues. Driven by the desire to reduce their dependence on India and to pursue independent foreign and economic policies, most of India’s South Asian neighbours (except Bhutan) joined the BRI. Pakistan was the first to sign on. A debilitating economic blockade by India in 2015 prompted Nepal to join in 2016, followed closely by Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, each seeking diversified economic prospects. Chinese projects are also attractive for South Asian states that see engagement with China as a hedge against traditional Indian dominance in the region.

India and China compete in South Asia to offer technical assistance and investments in infrastructure. The focus is on building connectivity via rail, road and sea to augment trade and security capabilities of small South Asian states.

Indian economic initiatives in Nepal, for instance, centre on connectivity and hydroelectric power projects. Managing the open India–Nepal border with the development of integrated border checkposts to aid the movement of goods and services is also critical. In Bangladesh, too, India’s lines of credit worth US$8 billion have contributed to several connectivity initiatives. Hybrid power projects, including wind farms, have been of interest to Sri Lanka, aided by Indian investments. Maritime cooperation and the development of coastal security infrastructure has been a focus for India’s cooperation with Maldives and Sri Lanka, which occupy a significant place in Modi’s Indian Ocean maritime strategy known as SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region).

Chinese initiatives in South Asia have been along similar lines. While Pakistan has benefited significantly from its involvement in the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, since 2015, China has stepped up its efforts in Nepal and Bangladesh. In 2018, China and Nepal agreed on the Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Transport Network to boost cross-border connectivity of railway, road and transmission lines. China granted Nepal access to several of its land and sea ports, particularly important given Nepal’s landlocked status. China is currently Bangladesh’s biggest trading partner and is reported to have invested an estimated US$9.75 billion in transportation projects in Bangladesh between 2009 and 2019. China has also emerged as Sri Lanka’s biggest trading partner and one of its largest creditors, accounting for about 10% of the country’s total foreign debt. Chinese funding was used to build roads, ports and airports. Sri Lanka and Bangladesh are also vital nodes in China’s Maritime Silk Road project.

To establish itself as the more reliable partner, India often asserts its cultural and historical links to South Asian states, with an emphasis on ‘common heritage and shared values’, or a ‘shared history’ in the case of Bangladesh. Covid-19 provided a further platform for India to outdo China’s efforts in the region. As China’s global reputation suffered at the height of the pandemic, India supplied crucial vaccines to South Asian states, except Pakistan, generating significant goodwill in the region.

There are, however, challenges to India’s neighbourhood policy. The cost of trading between India and South Asia remains high due to a lack of appropriate trade facilitation and logistical difficulties. Indian policy is often reactive to China’s rising influence, and policy mechanisms are insufficient to maintain a consistent level of engagement. For example, the inter-ministerial coordination group organised to promote relations between India and its neighbours met for the first time only this year. New Delhi has also ignored the recommendations of a bilateral report aimed at resolving tensions between India and Nepal.

India’s trust deficit in the region is another major impediment. Anti-India sentiment is common in South Asia, particularly in Nepal, Bangladesh and Maldives. Memories of India’s border blockades in Nepal and its interference in domestic political affairs in Nepal, Sri Lanka and Maldives are detrimental to the Indian case. The recent increase in religious polarisation and the revivalist nationalist ideas expressed in flippant statements by Indian political leaders have also fuelled worries in South Asian states.

So, I ask the question again, is this the right time for India to reassert its influence in South Asia? Yes, but not unless some of the structural problems are addressed. While South Asian neighbours are concerned about incurring large debts to Beijing, as in the cases of Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the historical baggage of being India’s ‘backyard’ makes them equally apprehensive of India’s dominance. The countries of the region play, to different degrees, the so-called China card against India—a trend that’s likely to continue, despite Indian efforts.

It’s easy to attribute all the problems and changes in Turkey to the whims of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s strongman largesse. His foreign-policy adventurism has led to increasing regional and international isolation and a transactional relationship with foreign partners, including NATO and the EU. In addition, loyalists and patronage networks have embedded themselves in think tanks, businesses and the foreign-policy bureaucracy. Turkey’s foreign policy these days is mainly about maintaining power at a growing economic and political cost to Turkish citizens.

Turkish foreign policy mandarins, however, have watched the changes in the past few years and are aware that the international order is shifting. The isolationist rhetoric of ‘America first’, combined with US domestic political apprehension towards further military engagement in the Middle East, has put constraints on fixing the ongoing problems in the US–Turkey alliance. The relationship has been deteriorating for quite some time and Turkey has sought support for its interests outside of its traditional Western-oriented relationships.

With a spiralling economy and low poll numbers for the ruling coalition, Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been searching for new partners to help it stave off economic disaster and the possible end of its 20-year tenure following elections scheduled for 2023.

As the global community focuses on the war in Ukraine, there’s another growing partnership of particular concern that should be viewed with caution: the increasing closeness between Beijing and Ankara.

China has entered into strategic partnerships with Saudi Arabia, Iran and other Gulf states. While most of Beijing’s engagement in the Middle East has centred on hydrocarbon resources, Turkey’s relationship with China is unique. China and Turkey find themselves among a growing bloc of authoritarian countries in the global order, and Beijing sees Ankara as an important player in changing the rules-based order given its influence and strategic position between the Mediterranean, Middle East and Eurasia.

China has played an integral part in Turkey’s foreign-policy vision for a while. Since the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, its new executive presidential system and the Eurasianist tilt in Turkish foreign policy have allowed Ankara to deepen its economic, security and military relationship with Beijing. Chinese power presents a viable alternative for economic and political support for Turkey’s ambitions in the world, without the baggage that relations with Russia bring.

Turkey’s pursuit of ties with other regional power groupings that China plays a definitive part in, such as the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, is one example of this tilt. These recalibrations signify the paradigm shifts within the Turkish political and foreign policy establishment over the two decades of AKP rule.

Closer relations with Turkey present China with an opportunity to effectively engage with and influence politics in the Middle East and to expand its influence and economic integration in the Mediterranean. Ties between Turkey and China can potentially affect Turkey’s relationships with the EU, NATO and the US more broadly, mainly because Turkey can use its relations with China as a balancer in what has become an increasingly transactional foreign policy with its traditional alliances.

NATO recently declared China a strategic priority given the systemic challenges China brings to the rules-based order, its confrontational stance towards Taiwan and its close ties with Russia. China responded by calling the NATO alliance a source of instability in the world and prone to Cold War thinking. Gaining leverage over Turkey gives China favourable circumstances to undermine the solidarity within NATO that has arisen with the Ukraine war. Turkey’s relations with Russia are a current example of this.

China doesn’t have the conditions attached to economic aid and human rights that are found in Turkey’s partnerships with the EU and US and so is very attractive to Erdogan for maintaining his authoritarian ‘new Turkey’. If Turkey were to embrace China, that could unhinge whatever leverage the EU, NATO and the US have on Turkey in human rights engagement, minority rights and stopping the rise of authoritarian politics in Turkey and the broader Middle East region.

Turkey has been a prominent voice of support for Uyghur rights throughout the world and was once a sanctuary for Uyghur dissidents from Xinjiang. As Turkey seeks economic benefits from China and gains an advantageous foothold with Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, activists are being deported and Turkey is no longer a haven.

The AKP could use Turkey’s position in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to champion Uyghur rights. Yet it has been reluctant to do so given the growing closeness between Ankara and Beijing. The AKP’s timidity means that the West loses one of the most prominent supporters of Uyghur rights in the Muslim world. Notwithstanding Albania’s contribution, this leaves countries like the US and Australia to continue to be vocal against China’s policies in Xinjiang.

Turkish opposition parties such as the Republican People’s Party and the Good Party have championed the Uyghur cause and could become a prominent voice against further Chinese integration if they were to win next year’s elections against Erdogan and the AKP.

Militarily, Turkey’s domestic arms industry is slowly replacing its need for NATO military hardware. Turkey’s endogenous Bayraktar TB2 drones have been critical in destroying Russian military hardware and have shifted the dynamics in the Ukraine conflict. Turkey may seek cheaper and more cost-effective military hardware or technology from China for its defence industry if relations with the US and NATO continue to deteriorate. Growing military and security ties between Ankara and Beijing have met challenges, and Chinese military equipment is still no match for US and NATO hardware.

Continued economic woes, unorthodox economic policy and terrible poll numbers could create the conditions for a change in government in 2023 in Turkey. Erdogan, however, will likely try to maintain power at all costs. Support from other authoritarian countries like Russia and China could ease the blowback from any election manipulation or chicanery. It’s unlikely that a change in government would undo the years of mistrust between Turkish policymakers and its traditional allies in NATO and the US. It will be difficult to bring Turkey entirely back into the Western fold. This makes it very likely that there will be further development and entrenchment of ties between Ankara and Beijing.

With NATO’s attention on the Russia–Ukraine conflict, and the EU and US dealing with their own authoritarian movements, the relationship between China and Turkey will likely fly under the radar. However, stronger ties between China and Turkey present a genuine and existential problem to Western cohesiveness in NATO, the EU’s stability, US power in the region and the balance of power in the Mediterranean. As China’s footprint grows in the Middle East and beyond, this developing relationship may become an issue sooner rather than later.

Little noticed publicly in either Australia or South Korea, Seoul has taken steps in recent months that suggest intent to forge closer strategic links with Canberra. The trend has accelerated under Korea’s new administration and should be factored in to Australia’s defence strategic review as an opportunity to strengthen our regional security and economic relationships.

During the June NATO summit attended by President Yoon Seok-yeol (who met with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese), Korean Prime Minister Han Duck-soo reportedly said: ‘Our priorities in values and national interests are changing’ and ‘I am not convinced that we are going to be affected much by China’s complaints.’

China’s demands irk Korea. Recognising Chinese power, proximity and major trade and investment interests, Korea will think hard before offending it, evidenced by Yoon—clumsily—not meeting US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in person in Seoul following her visit to Taiwan. And Korea will also not formally join the Quad, although Seoul is positive towards both it and possible cooperation with AUKUS.

But China’s recent aggressive military exercising and demands to limit operations of a US THAAD anti-missile battery in Korea (which, on its deployment in 2016, provoked tough Chinese economic sanctions) will strengthen already high levels of anti-China sentiment in Korea. It may lead to toughening of Seoul’s Indo-Pacific policy and greater willingness to engage substantively with Western powers and others concerned by the risks in China’s actions.

Like Australia, Korea faces a darkening geoeconomic and strategic outlook. Policymakers in the new Yoon administration will be weighing:

In short, Korea, like Japan, feels increasingly vulnerable and faces multiple challenges to its interests. But Korea is not sitting idle. It is building its already significant defence manufacturing industry—now a major export earner—to encompass not only ground force equipment but space, cyber, longer-range ballistic missiles, ballistic missile submarines, drones, fighter aircraft and a light aircraft carrier.

These capabilities help address the growing North Korean nuclear and conventional threat, and in particular respond to the North’s apparent effort to develop a battlefield nuclear weapon, an indication that the North hasn’t given up ambitions to blackmail the South, if not force a reunification on the North’s terms.

And the defence build-up goes well beyond that, enabling Seoul to play a much larger regional security role. The posture involves development of means to project power well beyond the Korean peninsula and to enhance deterrence against a more assertive China, even if the US alliance weakens. Korea has a long historical memory.

So where does Australia fit in? Australia has been a key member of the United Nations Command for Korea since the Korean War, and although this commitment has been small, it has been consistent. After the central US role, Australia’s probably the most significant. It has provided the basis for annual exercising with both countries in South Korea and a window into contingency warfighting and evacuation planning.

Until now, though highly valued by the US, the Australian commitment hasn’t been similarly valued by the myopic Korean military. But, driven by Yoon’s initial foreign policy advisers who have strong links with Australia, and a deteriorating regional and global security outlook, this view may be changing.

Aside from the common interests of the two countries, Korea eyes a potential significant defence market. Korea’s Hanwha Defence is building K9 self-propelled howitzers for the Australian Army in Geelong, and is bidding for the major contract to replace the army’s infantry fighting vehicles with a vehicle designed to meet Australian conditions. If it wins the contract, defence links could become much stronger.

But Korea, short of key resources, is also looking to Australia for secure supplies of hydrogen as it transitions from a fossil-fuel-dependent economy and away from Australian-supplied coal and liquefied natural gas. Australian rare earths and critical minerals will help reduce Korea’s vulnerability if China reimposes economic sanctions on Korea.

Hence outgoing President Moon Jae-in’s unexpected visit to Australia at the end of his term last November to engage potential suppliers and investors, particularly for critical minerals. A big resources trade delegation quickly followed in March, and an Australia–Korea Business Council delegation, focused specifically on these priorities, was welcomed in Korea in June.

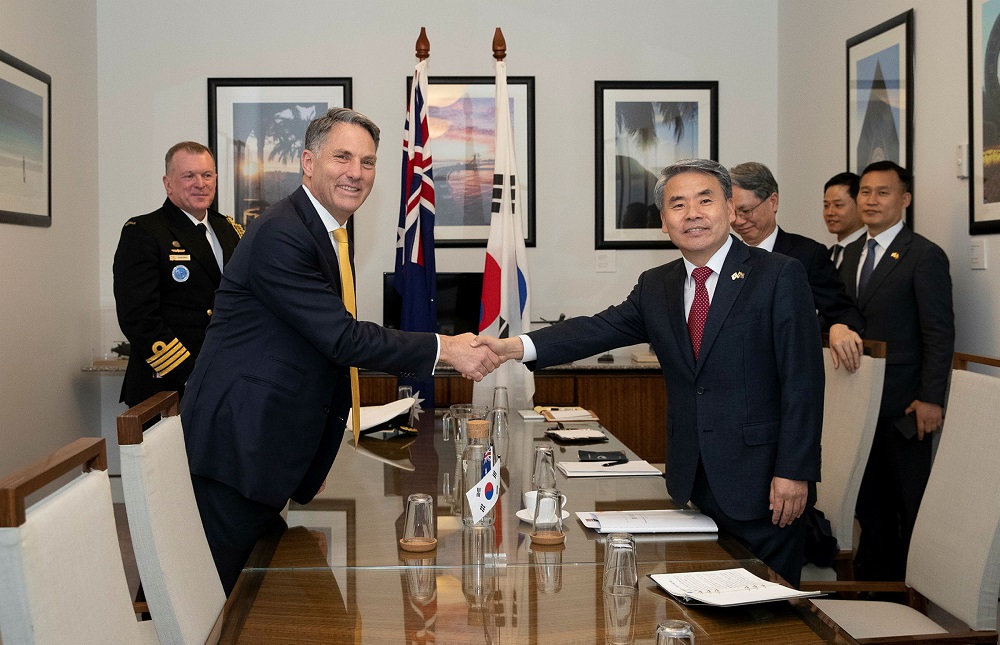

In turn, this was followed in July by a visit from Korea’s minister for defence acquisition, Eom Dongwhan, accompanied by a delegation from key defence manufacturers. Only three weeks later, in early August, Korea’s defence minister, Lee Jong-sup, visited both Canberra and Hanwha’s new Geelong plant, meeting with Australia’s defence minister, Richard Marles. These visits came early in the life of both new governments, indicating priority on both sides. The visits were not part of the routine structure of consultations between defence and foreign ministers, suggesting a wish to quickly build stronger defence links—and for Korea to promote its defence exports.

Australia’s defence strategic review should look closely at this pattern. Korea has a sophisticated defence industry, while its strategic priorities align increasingly closely with Australia’s. Until now, the opportunities in this new alignment have largely been overlooked—by both countries—but growing regional tensions suggest a rethink is timely.