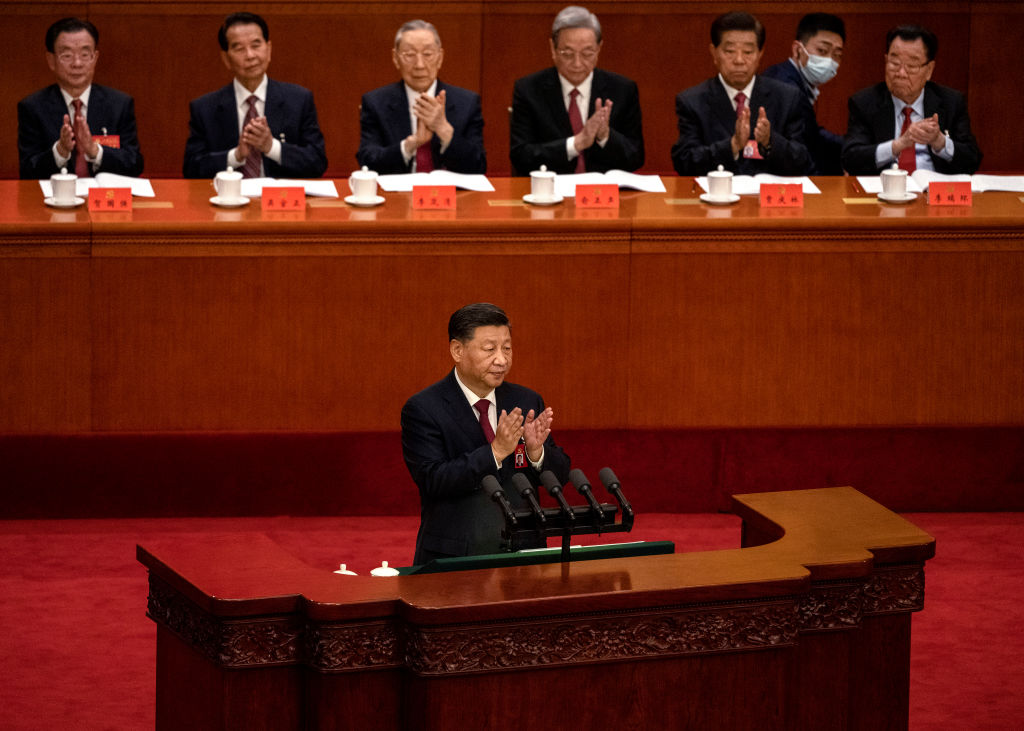

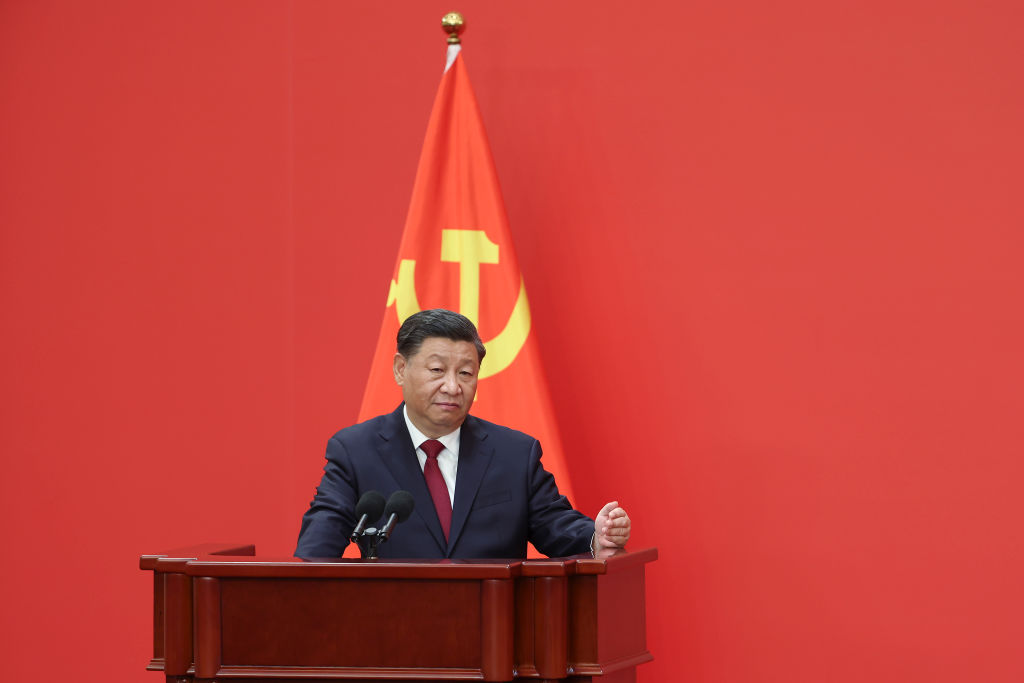

CCP constitutional change strengthens Xi’s power but avoids total personality cult

The Chinese Communist Party adopted a resolution on an amendment to its constitution at the closing session of the 20th national congress. The constitution describes the role of the party and its organisational structure, principles and ideology. It is amended at every national congress, so the fact of the amendment itself is not unusual, but analysing its content provides a clue as to the direction that the current administration is taking in terms of organisation and ideology for the next five years.

The focus of attention was on whether Chinese President Xi Jinping would revive the role of ‘chairman’ (党主席制), removed in a 1982 amendment, to further strengthen his authority as he starts his third term in office. The 20th congress highlighted Xi’s dominance over personnel matters, but the collective leadership system was maintained in the party’s institutional structure. The prohibitions against ‘personalist dictatorship’ (个人专断) and ‘cult of the individual’ (个人崇拜) from the 1982 amendment are retained in the current constitution.

Why was the party chairmanship not restored? One possibility is that there was opposition inside the party. The process of amending the party constitution involves discussions in the standing committee of the Central Political Bureau, the politburo and the plenary session of the CCP Central Committee. Xi himself reportedly hosted five roundtable meetings during this process. The move may have met with opposition from the congress presidential delegation, which includes retired leaders. Former president Jiang Zemin reportedly approved of Xi’s continuation as leader but expressed his opposition to a personalist dictatorship in the party.

Another possibility is that Xi himself decided not to pursue the change. He made major amendments to the constitution at the 19th party congress and therefore may have thought there was no need to make a major one this time around. Indeed, the previous amendments clearly stated the various terms relating to ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’ (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想) and strengthened the authority of the Commission for Discipline Inspection, furthering Xi’s consolidation of power. These amendments opened the door for his third term.

In light of the previous amendments, the main aim this time was to entrench the default line set by Xi’s previous administrations. One theme of the amendments was about strengthening Xi’s authority over the CCP. The revised constitution includes ‘virtue first, meritocracy’ (以德为先,先人为贤) as a criterion for the training and selection of cadres. As the appointments to the central committee and the politburo at the 20th congress confirm, virtue can be interpreted as loyalty to Xi and his ideology. By extending these criteria to the base level of the CCP, Xi may be attempting to spread his own power across all party organisational structures.

This year’s amendments also indicate an effort to strengthen Xi’s ideological power. The addition of party history education is likely related to Xi’s adoption of a new party history resolution (历史决议) in 2021. Such resolutions are significant documents for party history and this one will likely be used to legitimise the current regime. The 2021 history resolution made no mention of opposition to personalist dictatorship and the collective leadership system (集体领导); those words are explicitly stated in the resolution adopted in 1981 soon after the Cultural Revolution under Mao Zedong’s dictatorship. The new one, instead, focuses on praising Xi’s administration and thought. Now that Xi has taken over the authority to interpret party history, he has called on CCP members to study it.

In light of the major protests in Hong Kong in 2019, the change of wording to the unwavering adherence to the ‘one country, two systems’ (全面准确、坚定不移贯彻’一个国家、两种制度’) emphasises that only the CCP holds the right to interpret it. It was also newly stated that the CCP would oppose and curb the ‘Taiwan independence’ (台独). Until now, the CCP’s constitution had never mentioned a movement for Taiwan independence. This doesn’t necessarily mean that a Taiwan crisis is in the immediate future, but it at least reflects Xi’s impatience with the fact that his Taiwan policy is not working well.

Xi has increasingly made it clear that he is putting the party’s security and hold on power ahead of the economy. It’s symbolic that the phrase ‘sustainable development’ has been changed to ‘sustainable and safe development’, although the CCP continues to recognise that economic construction should be strongly promoted in the ‘socialist elementary stage’ (社会主义初期阶段). The previous amendment significantly strengthened the authority of the Discipline Inspection Commission, and the new one stipulates that discipline inspection groups will be set up in state-owned enterprises and social organisations.

The military–civil fusion development strategy, which was added in the 19th party congress amendments, was left in place, indicating that the CCP hasn’t dropped the strategy to siphon off resources from the private sector. However, the party’s strengthening of unilateral monitoring and mobilisation of society has led to a deterioration of economic activity in the private sector and an exodus of skilled workers. This is reflected in the prevalence of the online slang term ‘run philosophy’ (润学), which means emigration from China to a country whose people have freedom and human rights.

These modest amendments to the party constitution are important in that they avoid institutionalisation of a personalist dictatorship under Xi. On the other hand, Xi’s authority has been strengthened in terms of party organisation and ideology. From now on, China will be led by a highly homogeneous CCP made up of cadres who have pledged their loyalty to Xi personally. The growing homogeneity of the leadership will lead to greater exclusivity and a lack of other perspectives, which will weaken the party’s policy-correction function. As a result, the CCP is set to be more insensitive to international political changes and more assertive towards the outside world.