Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The failure of China’s zero-Covid policy is leading to a reassessment of Chinese power. Until recently, many expected China’s GDP to surpass that of the United States by 2030 or soon thereafter. But now, some analysts argue that even if China achieves that goal, the US will surge ahead again. So, have we already witnessed ‘peak China’?

It is just as dangerous to overestimate Chinese power as it is to underestimate it. Underestimation breeds complacency, whereas overestimation stokes fear; but either can lead to miscalculations. A good strategy requires a careful net assessment.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, China is not the world’s largest economy. Measured in terms of purchasing power parity, it became larger than the US economy in 2014. But PPP is an economist’s device for comparing estimates of welfare; even if China someday surpasses the US in total economic size, GDP is not the only measure of geopolitical power. China remains well behind the US on military and soft-power indices, and its relative economic power is smaller still when one also considers US allies such as Europe, Japan and Australia.

To be sure, China has been expanding its military capabilities in recent years. But as long as the US maintains its alliance and bases in Japan, China won’t be able to exclude it from the Western Pacific—and the US–Japan alliance is stronger today than it was at the end of the Cold War. Yes, analysts sometimes draw more pessimistic conclusions from war games designed to simulate a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. But with China’s energy supply exposed to US naval domination in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, it would be a mistake for Chinese leaders to assume that a naval conflict near Taiwan (or in the South China Sea) would stay confined to that region.

China has also invested heavily in its soft power (the ability to get preferred outcomes through attraction rather than coercion or payment). But while cultural exchanges and aid projects could indeed enhance China’s attractiveness, two major hurdles remain. First, by indulging in ongoing territorial conflicts with neighbours such as Japan, India and Vietnam, China has made itself less attractive to potential partners around the world. Second, the Chinese Communist Party’s domestic iron grip has deprived China of the benefits of the vibrant civil society that one finds in the West.

That said, the scale of China’s economic reach will remain important. The US was once the world’s largest trading power and bilateral lender. But now, nearly 100 countries count China as their largest trading partner, while only 57 have such a relationship with the US. China has lent US$1 trillion for infrastructure projects through its Belt and Road Initiative over the past decade, while the US has cut back aid.

China’s economic success story undoubtedly enhances its soft power, especially vis-à-vis other developing and emerging markets. And its ability to grant or deny access to its domestic market gives it hard-power leverage, which its authoritarian politics and mercantilist practices allow it to wield freely.

Where does that leave us in assessing the overall balance of power? Importantly, the US still has at least five long-term advantages. One is geography. The US is surrounded by two oceans and two friendly neighbours; China, by contrast, shares a border with 14 other countries and is engaged in territorial disputes across the region.

The US also has an energy advantage. Over the past decade, the shale revolution transformed it into a net energy exporter, whereas China has become ever more dependent on energy imports.

Third, the US derives unrivalled financial power from its large transnational financial institutions and the international role of the dollar. Only a small fraction of total foreign-exchange reserves is denominated in renminbi, while 59% are held in dollars. Though China aspires to expand the renminbi’s global role, a credible reserve currency depends on it being freely convertible, as well as on deep capital markets, an honest issuing government and the rule of law. China has none of these, making the renminbi unlikely to displace the dollar in the near term.

Fourth, the US has a relative demographic advantage. It is the only major developed country that is currently projected to hold its place (third) in the global population ranking. Seven of the world’s 15 largest economies will have a shrinking workforce over the next decade, but the US workforce is expected to increase by 5%. China, meanwhile, will suffer a 9% decline in its working-age population—which already peaked in 2014—and India will surpass it in terms of population this year.

Lastly, America has been at the forefront in the development of key technologies (bio, nano and information) that are central to this century’s economic growth. China, of course, is investing heavily in research and development, so that its technological progress no longer depends solely on imitation. It has managed to become competitive in fields such as artificial intelligence, where it hopes to be the global leader by 2030. US efforts to deprive China of the most advanced semiconductors may slow this progress, but they will not end it.

All told, the US holds a strong hand. But if it succumbs to hysteria about China’s rise or complacency about its ‘peak’, it could play its cards poorly. Discarding high-value cards—including strong alliances and influence in international institutions—would be a serious mistake.

One important issue to watch will be immigration. Around a decade ago, I asked former Singaporean prime minister Lee Kuan Yew whether China would surpass the US in total power any time soon. He said it would not, because America can draw upon and recombine the world’s talents in ways that simply are not possible under China’s ethnic Han nationalism.

For now, Americans have ample reason to feel optimistic about their place in the world. But if the US were to abandon its external alliances and domestic openness, the balance could shift.

Originally published 14 October 2022.

Rumours that President Xi Jinping was under house arrest amid a military coup in China—apparently driven by Falun Gong–linked social media accounts known for spreading factually problematic information—spread widely in late September. The available facts told most analysts that a coup probably hadn’t occurred, so it wasn’t surprising when Xi resurfaced on 27 September. That said, analysts shouldn’t be quick to deny that Xi’s position in power is more precarious than it might appear. No one knows for sure the degree to which his position is absolute. And neither, perhaps, does Xi himself. He may have positioned himself as ‘dictator for life’, but the forces of control are dynamic and he has survived in part because he doesn’t make that assumption himself.

Ahead of the 20th National Party Congress, kicking off on Sunday, we have been reminded that from the Chinese Communist Party’s perspective, power isn’t inevitable. We saw ramped-up prosecutions, continued calls for loyalty and warnings of colour revolutions. None of this is necessarily a sign of weakness or strength. The constant cycle of crisis or potential crisis is something the Chinese Communist Party also derives power from. It is a means for mobilising the party and the public, and for justifying intensified security measures and crackdowns. The threats are not imaginary.

A good rule of thumb for assessing political rumours from China is to consider them based on the balance of probabilities. If we’re going to talk about Xi’s power, it’s best to use the structure of power as a framework and shape the questions from there. As suggested to me by my colleague Peter Mattis, there are five main elements to being the foremost leader in the People’s Republic of China: gun, paper, pen, knife and blood.

The ‘gun’ is the People’s Liberation Army. The PLA is the party’s armed wing—not the country’s army—and is the guarantor of the party’s power. As Mao Zedong famously wrote, ‘Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.’

The ‘paper’ is handled by the central paper-pushers in the General Office of the Central Committee and the Organisation Department, which play an important role in the party’s management of itself.

The ‘pen’ is the propaganda apparatus. The gun defeats enemies, but the pen, as Mao noted, unites the people (under the leadership of the party) and attacks and destroys the enemy. It also defines and interprets party orthodoxy.

The ‘knife’ is the internal security apparatus (the Ministry of State Security and Ministry of Public Security) responsible for social and political control.

And finally, the ‘blood’, representing the core families of the party. They hold massive wealth, much of which sits outside of China, and command their own loyalists by extension.

Mao controlled these elements as he rose to power and as he stayed in power after the forming of the PRC. As chronicled in Gao Hua’s meticulous study of Mao’s seizure of power, he began with his base in the Red Army and steadily moved to control how the central party machinery functioned and the propaganda organs. Xi has gone after each of these areas, it would appear with great success.

Early in his tenure, Xi began an anti-corruption campaign targeting the PLA. Two former vice-chairmen of the Central Military Commission were singled out for particular scrutiny: General Xu Caihou, who died of cancer in 2015 a year after being put under investigation, and General Guo Boxiong, who was sentenced to life in prison. Another PLA officer, General Gu Junshan, former deputy director of the PLA General Logistics Department (since rebranded as the Logistic Support Department), was given a suspended death sentence.

As analyst Kevin McCauley wrote in 2015, much of the early anti-corruption campaign and personnel changes focused on logistics and political officers responsible for money, personnel, materiel and construction projects. The significance of these posts is even more crucial in a political context, because the party’s ability to rely on the PLA to mobilise in a crisis requires political loyalty as well as preparedness for military action.

At the same time, Xi put himself in charge of huge PLA reforms with the establishment of the Leading Small Group on Deepening Reform of National Defence and the Military in 2014. He oversaw the establishment of the PLA Ground Force headquarters, the PLA Rocket Force and the PLA Strategic Support Force in 2015, and directed a major PLA restructure that began in 2016.

Xi was quick to focus on ensuring that the propaganda apparatus was on his side. Propaganda controls party dogma and helps Xi to project an image of strength, domestically and internationally. Huang Kunming, a Xi ally, was appointed head of the Central Propaganda Department, under the CCP’s Central Committee, in 2017. During Xi’s tenure, the department has tightened its control over media, with the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television being moved from the State Council to the Central Propaganda Department’s control in 2018. This strengthened Xi’s ability to define how the party’s theory about achieving national rejuvenation suggested Beijing’s direction in light of real-world events.

Like every party general secretary, Xi has his supporters in key positions, like the person running the CCP General Office. He also has enough control of the party discipline and anti-corruption organisations to use them against political opponents—as he clearly did in July with the sentencing of white-glove financiers for his political opponents and in September with the sentencing of a number of officials linked to the Ministry of Public Security.

To control the knife, Xi launched a rectification campaign against the political–legal apparatus last year. One of the most senior officials taken down in the anti-corruption campaign, Zhou Yongkang, had most recently been head of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, an area of the party-state apparatus that had resisted Xi’s efforts to politicise everything. Xi had either neutralised people or put his own in places of political power. Zhao Kezhi, who held the post of minister of public security, was recently replaced by Xi ally Wang Xiaohong. Zhao had earlier been replaced by Wang in the concurrent role of party secretary in the Ministry of Public Security.

Xi has generated the most resistance from the CCP’s elite families. The question here is whether the old power-broker system continues to function and has enough influence to unseat someone like Xi. It’s possible that the system has changed so fundamentally that the party elders can no longer act as a check on Xi.

The video message of Song Ping, the elderly representative of a significant PLA faction, is one of the most dramatic signs that the party’s bloodlines may be opposed in the current moment. (It is worth noting that signs of such dissatisfaction go back years.) As commentator Dimon Liu pointed out in June, criticisms of Xi by individuals writing from within the PRC have been published. None of those people are known to have been arrested, which is only possible if they are being protected by someone powerful in the PRC.

Yet, despite his consolidation of power, Xi has clearly made some mistakes.

The dynamic zero-Covid policy has created widespread dissatisfaction and left a trail of economic damage. Its disruptions have encouraged companies to think more directly about diversifying supply chains and forced new conversations about quality of life.

Xi’s decision to enter a ‘no limits’ partnership with Russia on the eve of its invasion of Ukraine put the PRC on the other side of an issue that has united the US and Europe. Although European countries are grappling with the energy crisis brought about by their dependence on Russian gas, new conversations are beginning about dependence on PRC supply chains.

Xi’s pressure campaign on Taiwan has closed off pathways for peaceful unification and encouraged the US to more explicitly state its support for Taipei. Last month, President Joe Biden for the fourth time stated that America would defend Taiwan if the PRC launched an unprovoked attack.

Xi also has doubled down on state-owned enterprises leading the economy, refusing to look at rebalancing the economy towards consumer demand. Now the headwinds are rising quickly and economic forecasts look increasingly grim.

So, the control solidified early on could be wearing down, and we are left to ask, by how much? At what point does dissatisfaction become opposition? Have generational change and Xi’s anti-corruption drive disrupted the familial and patronage networks that gave party elders power in the past?

For the CCP, the party congress is not when and where major political and personnel decisions are made. It is the platform the party uses to formalise and announce what already has been decided in backrooms. It isn’t always clear what those decisions might be until they become known to the world. It’s even possible that a palace coup and political manoeuvre forcing Xi out could go unmarked until the party congress provides the opportunity to tell the world.

In uncertain times when the rules have been cast out, regional specialists should be more open to possible discontinuities. As former director of US Central Intelligence Robert Gates noted, ‘Area experts, country experts, are sometimes the very last to see a revolutionary change coming, because the history of most countries is a history of continuity. In discontinuity, they find too many reasons why that won’t happen.’

The history of the CCP is littered with political crises, the most dangerous of which involved questions of leadership succession and economic policy. Even if the coup rumours were a false alarm generated by wishful thinking, the current dynamics should have us systematically assessing potential discontinuities because of the potential for another crisis to emerge that tests the resilience of the CCP. Xi’s behaviour shows that he knows that the struggle for power is never over. We should take note of this in our own thinking.

The world has witnessed the outbreak of economic warfare this year, quite unlike anything seen since the end of World War II.

The machinery of economic sanctions, which has been honed over decades against minor dictatorships, has been turned by the West on Russia with a ferocity never before applied to a major economy.

Russia has been using its role as the world’s largest energy exporter to strike back, curbing supplies to Europe as the northern winter approaches in the hope that freezing its citizens will persuade their governments to cut support for the Ukraine.

At the same time, Washington has choked the flow of US technology to China and is trying to enlist allies to do the same, with the objective of maximising the West’s technological lead and, implicitly, retarding China’s economic development.

China has not yet found ways to retaliate against the US but is continuing its campaign of economic intimidation against smaller nations, including Australia and Latvia, by closing its markets to selected exports.

After decades during which the rapid growth in international commerce was seen as a desirable goal in itself, the outbreak of economic hostility among major powers marks a structural break.

One lesson from the economic warfare of 2022 is that it doesn’t bring quick results. Another is that stopping a country from importing can be more disruptive than stopping it from exporting. That’s because imports find their way into so many nooks and crannies across a nation, whereas export industries tend to be fairly concentrated. And perhaps a third is that commodities are less effective as economic weapons than high-end technology.

While most economists, including those at the International Monetary Fund, expected that the loss of around 40% of Europe’s pre-Ukraine-war gas supply would result in a recession, the latest figures show that manufacturing production across the European Union is at record levels, with nearly all EU countries producing more in September 2022 than they did a year earlier.

A Financial Times newsletter reports that an astonishing 75% of German industrial companies using gas for their primary energy source have been able to reduce their gas use without having to cut production. Nearly 40% say they could cut their usage further without sacrificing production. Similarly, in Italy, industrial gas consumption has dropped 24% below the 2019–2021 average, but industrial output has increased.

There’s a widespread view in Europe that the gas shortages are encouraging a faster shift away from fossil fuels and towards renewables. There’s also confidence that Europe has accumulated sufficient gas reserves to see it through the winter, although the International Energy Agency warns that it may be harder for Europe to replenish those reserves ahead of the 2023–2024 winter if the supply cuts continue.

Europe and the West have been targeting Russia’s energy exports. Russian coal, which used to supply around 18% of the global thermal coal trade, has come under sanctions, meaning ships carrying it can’t get insurance or trade finance from European or US institutions. The West is also imposing a cap on the price of Russian oil and is planning to do the same on Russian gas. The oil price cap of US$60 a barrel, intended to stop Russia from profiteering from the war, has so far had no effect because the price for Russian oil has fallen below that. A softening world economy means that the loss of Russian supplies is no longer squeezing the oil price. Gas and coal prices have also eased, although they remain elevated.

From Moscow’s perspective, the West’s economic sanctions haven’t brought the Russian economy ‘to its knees’ as some expected. The IMF’s latest forecast is a 3.4% contraction this year and another 2.3% in 2023. Both Russian businesses and consumers are making do without supplies from the West. As an excellent Financial Times report shows, smuggling is occurring on a large scale through former Soviet states like Kazakhstan and Armenia, and manufacturers are being innovative in replacing Western supplies. A forklift manufacturer now uses motors made in Belarus rather than Japan. The microchips that used to control tractors have been replaced by simpler chips from Asia. It’s harder to improvise with servers and other high-end electronics, and smuggled goods don’t carry warranties or after-sales service.

In the longer term, consumers and businesses will adjust to the more limited choice of goods and poor product quality, as was the case in the Soviet Union. The FT report cites a Russian oligarch saying, ‘There will be more paper in the sausage.’ Russia’s imports are down by about a quarter. It is estimated that most Russian industry relies on imports for at least half its inputs. Russia will also probably never regain access to European markets for its piped gas and it will take many years to divert it to Asia.

The impact of US efforts to sever China’s access to Western technology will also take time to emerge. There has been a profound shift in Washington’s attitude towards global business. Open trade served US strategic interests during the great expansion of US multinationals from the 1950s to the 1980s, helping cement the US’s place as a global power. The US is now less convinced that, for example, the operations of Apple or Tesla in China are fundamental to its interests. Businesses will always have an influential voice in Washington, but the US is more concerned with the advantages, both economic and strategic, from technological leadership than with the benefits that flow from offshore investment by US multinationals, which was the logic underpinning Pax Americana in the decades after World War II.

As US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan explained in September, the US had always sought to stay a step ahead of rivals on technology, but that was no longer enough. ‘Given the foundational nature of certain technologies, such as advanced logic and memory chips, we must maintain as large of a lead as possible.’ The US national security statement released the following month set an objective for the US of ‘outcompeting [China] in the technological, economic, political, military, intelligence, and global governance domains’.

The export controls imposed in October prevent US companies from selling advanced microchips or chipmaking equipment to China, while a growing number of Chinese technology companies have been placed on the US ‘entity list’, which prohibits any US sales at all. The new US CHIPS and Science Act prevents any tax credits from going to companies that build or expand fabrication operations in China.

The effectiveness of this strategy will turn on how successful China is at developing its own indigenous capacity and on the success of the US in gathering the support of key allies like South Korea, Japan, the Netherlands and Taiwan. The Netherlands is home to ASML Holding, the most important manufacturer of high-end chip-making equipment, and is under pressure to strengthen its controls on exports to China. At the G20 meeting in Bali last month, Chinese President Xi Jinping sought out Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

Xi’s G20 meeting with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is yet to be followed by any relaxation of Chinese import barriers, although the end-of-year visit to China by Foreign Minister Penny Wong has raised hopes. China would in particular like to resume access to Australian coal. Although the barriers have caused some pain in the wine and lobster industries, other exporters have largely diversified away from China.

Much like the Ukraine war, it’s hard to see what would bring a return to the days of economic peace.

On 9 December 2022, Indian and Chinese troops clashed in the Yangtse area along the India–China border. The confrontation in the Tawang region was the most serious skirmish between the two sides since their deadly clash in the Galwan Valley in 2020.

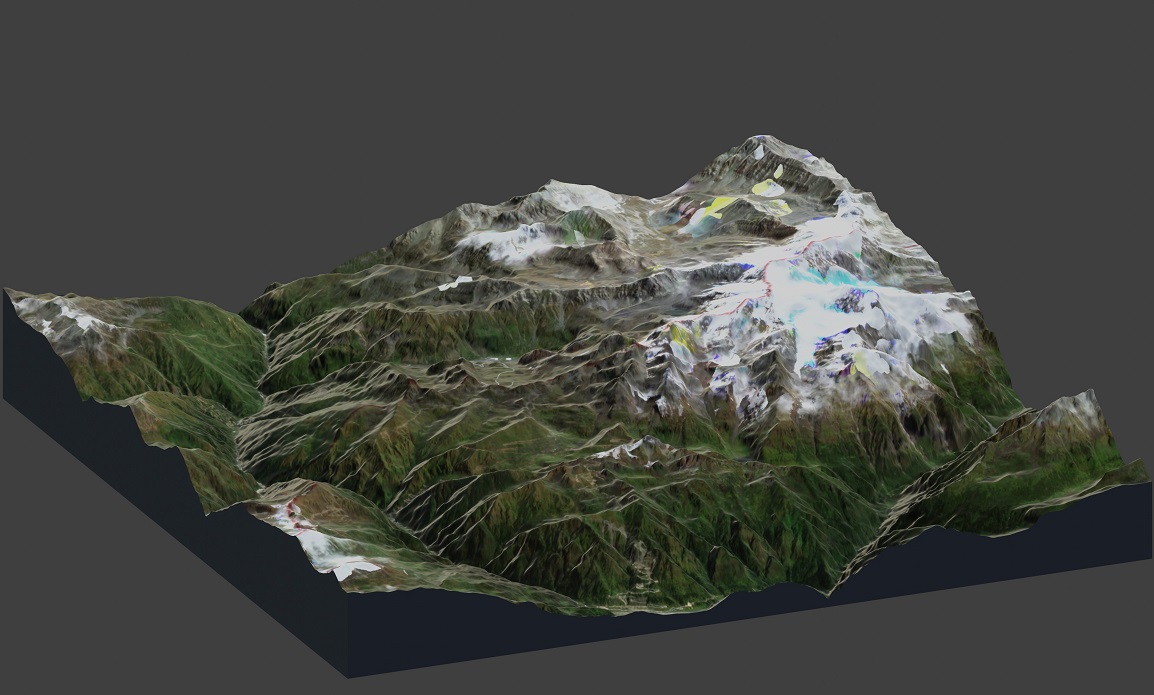

ASPI has released a new visual project that analyses satellite imagery of the key areas and geolocates military, infrastructure and transport positions to show new developments over the past 12 months.

This project contextualises India–China border tensions by examining the terrain in which the clash took place and provides analysis of developments that threaten the status quo along the border—a major flashpoint in the region. We find that the recent provocative moves by Chinese troops to test the readiness of border outposts and erode the status quo have set a dangerous precedent.

Tawang is strategically significant Indian territory wedged between China and Bhutan. The region’s border with China is a part of the de facto but unsettled India–China border, known as the Line of Actual Control, or LAC.

Within Tawang, the Yangtse plateau is important for both the Indian and Chinese militaries. With its peak at over 5,700 metres above sea level, the plateau enables visibility of much of the region. Crucially, India’s control of the ridgeline that makes up the LAC allows it to prevent Chinese overwatch of roads leading to the Sela Pass—a critical mountain pass that provides the only access in and out of Tawang. India is constructing an all-weather tunnel through the pass, due to be completed in 2023. However, all traffic in and out of the region along the road will still be visible from the Yangtse plateau.

Our analysis reveals that rapid infrastructure development by China along the border in this region means that it can now access key locations on the Yangtse plateau more easily than it could just one year ago.

India’s defences on the plateau consist of a network of six frontline outposts along the LAC. They are supplied by a forward base about 1.5 kilometres from the LAC that appears to be approximately battalion sized. In addition to this forward base, there are more significant basings of Indian forces in valleys below the plateau.

Although Indian forces occupy a commanding position along the ridgeline, it is not impregnable.

The access roads leading from the larger Indian bases are extremely steep dirt tracks. Satellite imagery shows that these roads are already suffering from erosion and landslides due to their steep grade, environmental conditions and relatively poor construction.

While China’s positions are lower on the plateau, it has invested more heavily than the Indian military in building new roads and other infrastructure over the past year.

Several key access roads have been upgraded and a sealed road has been constructed that leads from Tangwu New Village to within 150 metres of the LAC ridgeline, enhancing China’s ability to send People’s Liberation Army troops directly to the LAC. There is also a small PLA camp at the end of this road.

It was the construction of this new road that enabled Chinese troops to surge upwards to Indian positions during the 9 December skirmish.

The skirmish that took place between Chinese and Indian troops on the Yangtse plateau stems from this new infrastructure development.

Strategically, China has compensated for its tactical disadvantage with the ability to deploy land forces rapidly into the area. In small skirmishes, the PLA remains at a disadvantage because more Indian troops are situated on the commanding ridgeline that makes up the LAC. But in a more significant conflict, the durable transport infrastructure and associated surge capability that the PLA has developed could prove decisive, especially in contrast to the less reliable access roads that Indian troops would be required to use.

This intrusion, and subsequent clashes—which the Indian government claims the Chinese troops provoked—likely served to further normalise the presence of Chinese troops immediately adjacent to the LAC. This is a goal that the PLA appears to be working towards across the border and is part of China’s long-term strategy. By engaging in such an intrusion, the PLA is able to strategically position any ‘retreat’ to a higher location on the plateau.

Recent developments around Galwan and Pangong-Tso have shown that, where there is the political will, tense situations along the LAC can be disengaged with the involvement of both sides. In these areas, successful redeployment to positions back from the LAC has greatly reduced the risk of conflict.

Unfortunately, on the Yangtse plateau, the opposite is occurring. The recent provocative moves by Chinese troops to test the readiness of border outposts and erode the status quo have set a dangerous precedent.

China’s rapid infrastructure development along the border has created an escalation trap for India. It is difficult for India to respond to this new reality without being seen as escalating the situation. It is also difficult for it to unilaterally de-escalate without strategic concessions that would endanger its positions. India’s response has been to increase its vigilance and readiness along the border, including surveillance.

However, it is important to pursue non-military and multilateral measures in parallel to reduce the risk of accidental escalation and to position these incidents as a significant threat to peace and order in the Indo-Pacific. As part of this, India should seek and receive support from the international community to call out China’s provocative behaviour on the border.

Regional governments, including Australia’s, must pay greater attention to clashes on the India–China border. Continued escalation, including the potential of more serious clashes along the LAC, could become a major driver for broader tensions.

This new work by ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre builds on satellite analysis that it carried out in September 2021, focused on the Doklam region.

When news of China’s new vulnerability reporting regulations broke last year, fears circulated that Beijing would use the law to stockpile undisclosed cybersecurity vulnerabilities, known as ‘zero days’.

A report released last month by Microsoft indicates that these fears have likely been realised.

The Regulations on the Management of Network Product Security Vulnerabilities require that any vulnerability discovered within China be reported to the relevant authorities within two days. For software and products developed outside mainland China, this is particularly problematic because the Chinese government now has access to vulnerabilities before vendors can patch them. This lead time enables Beijing to assess vulnerabilities for its own operational advantage—in other words, to see whether they can be exploited for use in a cyberattack against foreign entities.

By developing a better understanding of the structure of China’s system of cybersecurity governance, we might improve our grasp of the wave of new legislation and reforms occurring in China’s cybersecurity sector. This in turn will enable us to better understand how laws such as the vulnerability reporting regulations contribute to President Xi Jinping’s vision to make China a ‘cyber powerhouse’ (网络强国), and will give policymakers greater insights into the threats posed by Beijing’s cyber capabilities.

China’s cybersecurity landscape comprises a complex system, or xitong (系统), of command structures and organisational bodies that operate with an interwoven network of laws, supporting regulations and guidelines to enforce China’s overarching cybersecurity strategy. Given the opacity of the Chinese system of governance and recent reforms that have dramatically changed the nation’s cybersecurity sector, attributing responsibility and decoding the hierarchical structure of this xitong is difficult. Through careful analysis of primary and secondary sources, ASPI has developed new insights into the major players and the system under which they are organised.

Driven by a desire to better understand how China’s system of cybersecurity governance operates and to discover how entities have access to cybersecurity vulnerabilities, I have mapped the organisational structure and, in doing so, created a resource for others working in this area.

As part of this work, I delved into how the system facilitates China’s exploitation of vulnerabilities for its offensive cyber activities.

Article 7.2 of the regulations states that all vulnerabilities must be reported to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s ‘network security threat information-sharing platform’ within two days of being discovered. However, according to a government-issued infographic, sharing of vulnerabilities with additional entities is also encouraged. These include the National Vulnerability Database of Information Security, which sits under the China Information Technology Security Evaluation Centre. Given that both of these entities are overseen by the Ministry of State Security, it’s reasonable to assume that the ministry has access to all vulnerabilities reported to them.

The Ministry of State Security is China’s foremost intelligence and security agency. It has been found to have routinely conducted cyber-enabled espionage and is linked to at least two advanced persistent threats—APT3 (also known as ‘Gothic Panda’) and APT10 (‘Stone Panda’). In 2017, researchers at Recorded Future concluded that the ministry’s access to vulnerabilities might ‘allow it to identify vulnerabilities in foreign technologies that China could then exploit’. The same group later published a finding that the National Vulnerability Database of Information Security had manipulated the publication dates of vulnerabilities in an effort to cover up China’s process of evaluating high-threat vulnerabilities to see whether they had ‘operational utility in intelligence operations’.

Last month’s Microsoft report indicates that Chinese state has probably taken advantage of the new vulnerability reporting regulations, stating: ‘The increased use of zero days over the last year from China-based actors likely reflects the first full year of China’s vulnerability disclosure requirements for the Chinese security community and a major step in the use of zero-day exploits as a state priority.’ CrowdStrike’s 2022 global threat report also identified China as a ‘leader in vulnerability exploitation’ and reported a six-fold increase in the number of vulnerabilities exploited by ‘China-nexus’ actors, representing a major shift in the kind of cyberoperations China is conducting.

The picture we are able to build of the cybersecurity governance structure fits with China’s overarching strategy of military–civil fusion (军民融合) in that Beijing has sought to engage civilian enterprises, research and talent in the cybersecurity sector to bolster military objectives. The strategy’s goal is to deepen China’s defence mobilisation so that civil society can be used in both war and strategic competition. Military–civil fusion is not a new strategy for China, but it has been increasingly prominent under the leadership of Xi and is a component of nearly every major strategic initiative since his ascension to the presidency.

The Chinese intelligence apparatus’s exploitation of these vulnerability reporting regulations is one further example of how Beijing has leveraged the civilian cybersecurity sector to advance the state’s offensive cyber capabilities.

In October, the US introduced a ban on exports to China of cutting-edge semiconductor chips, the advanced equipment needed to manufacture them and semiconductor expertise. The export controls are Washington’s most serious attempt to undermine China’s military modernisation and the most damaging measures US President Joe Biden has taken against China.

Advanced semiconductors underpin everything from autonomous vehicles to hypersonic weapon systems. Chips are imperative to the defence industry and technologies of the future. By targeting this critical input, the Biden administration aims to freeze China’s semiconductor suite at 2022 levels and impede its military development.

China will probably struggle to maintain its rapid advances in artificial intelligence, quantum and cloud computing without access to US technology and expertise. Chipmakers like the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation—China’s largest logic chip producer—will lose access to machine maintenance and equipment replacement under the new controls.

US chip equipment suppliers like Lam Research, Applied Materials and KLA Corporation have suspended sales and services to Chinese chipmakers, while ASML Holding, a Netherlands-based supplier, told its US staff to stop servicing Chinese customers until further notice.

The new controls exploit China’s weaknesses in developing talent and research. They require all US citizens, residents and green-card holders—including hundreds of ethnic Chinese educated and trained in the US—to seek permission from the US Department of Commerce to work in Chinese fabrication plants. Since such permission is unlikely to be granted, US citizens working at Chinese semiconductor companies will be forced to sacrifice their citizenship or their jobs. Most will have to give up their current jobs. Indeed, Yangtze Memory Technologies Corp has already asked core US staff to leave the company.

Despite the bleak short-term outlook, it is wrong to assume that US controls will hobble China for years. In the case of nuclear weapons, significant resources were poured into acquiring bomb technology once political leaders decided that they were essential for national defence. That effort inevitably starved other sectors, but more often than not successfully delivered nuclear weapons programs.

Now that advanced semiconductors are seen as essential to national defence, Beijing is adopting a ‘whole of the nation’ approach and investing national resources into the industry. Many engineers and computer scientists are likely to be assigned to semiconductor design and manufacture, assisted by espionage against US, South Korean, Taiwanese, Japanese and European chip firms.

The export controls won’t cripple the Chinese military. According to a recent RAND Corporation report, China’s military systems rely on older, less sophisticated chips made in China on which US export controls will have no effect. If China needs more advanced chips for AI-driven weapons systems, it can likely produce them, albeit at a very high cost. Many semiconductor industry experts agree that China has the technical capability to produce cutting-edge chips yet lacks the commercial capability to scale up production. This means that the US ban will have less effect on weapons systems, instead delaying the rollout of civilian applications such as autonomous vehicles.

Nor will US semiconductor firms emerge from the sanctions unscathed, given that many have China as their largest market. China accounts for 27% of sales at Intel, 31% at Lam Research and 33% at Applied Materials. Both Applied Materials and Nvidia expect the new export controls to cut US$400 million (6% and 7%, respectively) from next quarter’s sales. Lam Research—one of Yangtze Memory Technologies Corp’s largest suppliers—expects the controls to cut a whopping US$2.5 billion (15%) from 2023 sales.

These dramatic cuts come at a particularly difficult time for the US semiconductor industry, which is experiencing falling revenue and increased input costs. By one estimate, the damage US sanctions inflict on research and development and capital investment in the Western semiconductor industry ‘will exceed Washington’s modest subsidies for the chip industry by a factor of five or more’.

Tit-for-tat retaliation against the US is not an option for China, given its heavy reliance on foreign technology. Any reciprocal measure would inflict more damage on China itself. Punishing US companies with big exposure in China—like Nike or Apple—would harm the Chinese labour market since those firms employ many Chinese citizens. Other foreign supply chains and Chinese businesses supplying Nike and Apple would also suffer.

Imposing export controls on products China dominates, like rare earths or pharmaceutical ingredients, would accelerate the US movement to ‘reshore’, onshore and ‘friend-shore’ manufacturing of those products, as was the case with Japan in 2012.

Instead of overt retaliation, China will probably seek alternatives to US chip technology. But since alternatives are decades away, intellectual property theft and the nationalisation of foreign semiconductor firms could spike.

Whether US chip controls represent a stand-alone policy or foreshadow sanctions across a wider range of high-technology sectors is unclear. In the run-up to the 2024 US presidential election, many Republicans will call for harsher controls. At his recent meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the G20 summit, Biden sought to tamp down US–China hostilities. But unless he resists calls from the US ‘China hawks’, Biden could find himself dragged into a second cold war.

China has lately experienced its largest and most politically charged protests since the pro-democracy movement in 1989 ended in a massacre by government forces on Tiananmen Square. The recent social eruption should not be surprising; frustrations over the Chinese government’s rigid zero-Covid policy have been brewing for a long time. Yet the ruling Chinese Communist Party apparently did not see the protests coming, despite operating an all-pervasive and deeply intrusive surveillance apparatus. Now, the central government has announced that it will accelerate the shift away from zero-Covid with a broad easing of restrictions. After publishing a set of 20 guidelines for officials to follow last month, it has now cut the list down to 10.

Faced with the protests, President Xi Jinping’s government eschewed brutal Tiananmen-style suppression of the demonstrations. While large numbers of police have been deployed to protest sites, they have avoided bloody ‘crowd-control’ tactics and mass arrests, preferring instead to identify and intimidate protesters using cell-phone tracking technology. But CCP leaders also warned that a ‘resolute crackdown’ was coming. According to Chen Wenqing, the CCP’s newly installed domestic security chief, the authorities will target ‘infiltration and sabotage activities by hostile forces’ and ‘illegal and criminal acts that disrupt social order’.

While China’s government has sent a relatively clear message about the fate of the protests, its stance on zero-Covid has been hazy and inconsistent, with restrictions being relaxed only in some cities, such as Guangzhou, Hangzhou and Shanghai. In recent days, the phrase ‘dynamic zero-Covid’ (dongtai qingling) seemed to disappear from state-run media.

Still, uncertainty reigned, because no senior Chinese official had publicly stated that the zero-tolerance approach is being fully abandoned. Instead, Vice Premier Sun Chunlan, who is overseeing the pandemic response, has acknowledged the ‘weakening severity of the Omicron variant’ and said that the fight against Covid-19 was entering a ‘new phase’.

With little direction from above, local governments have been adopting widely different policies. For example, though Shanghai’s municipal government announced an easing of some rules—as of 5 December, a negative Covid test was no longer be required to take public transportation or visit parks—it has again shut down the recently reopened Disneyland.

Chinese leaders’ refusal to take a clear stance on zero-Covid is pure politics. The central government has been reluctant to take responsibility for the decision, because policymakers do not want to be blamed for whatever surge in infections, hospitalisations and deaths follows a reopening. The new guidelines may be looser than what came before, but they do not necessarily represent an end to zero-Covid.

Local officials have been playing politics too. If they have been relaxing pandemic restrictions, it’s because they believe that doing so will serve their interests well enough to merit the risk to public health. If they have stuck with harsher restrictions, it reflects their calculation that the immediate hit to their popularity would be dwarfed by the impact of becoming a scapegoat for any wave of cases.

But perhaps the clearest and most worrying evidence of the politicisation of public-health decisions is the Chinese authorities’ refusal to approve the more effective mRNA vaccines produced by Western companies. Though these vaccines would help to make the departure from zero-Covid safer, especially for under-vaccinated elderly Chinese, China’s leaders apparently view the use of Western vaccines as a blow to national pride and an admission of past mistakes.

Looking ahead, China’s leaders can probably count on the security forces to snuff out new protests, thereby allowing the CCP to reassert control and downplay people’s frustrations. But the reluctance to devise a comprehensive and systematic exit strategy from Covid—and to take responsibility for its outcomes—could result in China experiencing the worst of both worlds.

If there’s still confusion over Xi’s commitment to zero-Covid and the central government’s reopening plans, that will produce a chaotic response at the local level and the continued enforcement of ever-changing pandemic restrictions will strain state attention and resources, while stoking popular frustration. At the same time, a loosening of restrictions that is not accompanied by effective public-health measures—such as a rapid mass immunisation campaign using Western vaccines—will send infection rates soaring, overwhelming China’s healthcare system.

Xi needs to act fast to avert this outcome, not least by ordering the immediate approval and import of mRNA vaccines. Such a move would demonstrate not only political courage but also political savvy, because it would go a long way towards repairing the damage done to Xi’s image by the anti-lockdown protests that rocked his government at the end of last month.

As Australia’s foreign and defence ministers and the US secretaries of state and defence prepare to meet for the annual AUSMIN consultations, ASPI is releasing a volume of essays exploring the policy context and recommending Australian priorities for the talks. This is an abridged version of a chapter from the collection, which will be published this week.

It is probably inevitable that the defence dimensions of AUSMIN receive the most attention, especially given the ongoing war in Ukraine, the announcements on a pathway to nuclear-powered submarines and the defence strategic review due in March.

The emphasis on defence reflects the strategic context and the need to demonstrably affirm and strengthen the military alliance. However, the integration of foreign and defence policies and messaging is essential for the Australia–US alliance to perform effectively in this region, including in its most important contemporary task of managing China.

The foreign policy priorities of countries in the Indo-Pacific—from development to respect for sovereignty and the centrality of regional institutions—need to have due prominence not only in the AUSMIN joint statement, but also at the media conference and side events. To succeed bilaterally and regionally, AUSMIN will need to project the robust nature of the Australia–US alliance as well as the benefits it brings to the Indo-Pacific.

Setting the tone

AUSMINs are generally led by the respective foreign ministries. Notwithstanding the war in Ukraine and the AUKUS arrangement, this should still be the case.

Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken will want to ensure that the Australia–US partnership signals both strength and resolve, as well as a holistic and positive vision for the Indo-Pacific that reflects regional priorities, including sovereignty and economic development. They’ll aim to present a realistic view of the challenges facing the region, while emphasising stability and allaying concerns about a US–China conflict.

This all rests on clear signalling that the US is irreversibly committed to the Indo-Pacific, despite economic challenges at home, long-term support for Ukraine and concerns over Iran. US credentials need some repair after President Donald Trump’s piecemeal attendance at regional forums and the underwhelming delivery of President Barack Obama’s ‘pivot’ to Asia.

Any positive vision for this region must also weather an inevitable tide of propaganda and disinformation from Beijing, which will claim the US views the region solely through the lens of great-power confrontation and will dismiss Canberra as a US stooge. We need to work together to address Beijing’s false narratives, as we’ve had to do when explaining AUKUS to the region. Silence on our part only allows Chinese narratives to take deeper root.

The recent bilateral meetings in Bali with Chinese President Xi Jinping don’t alter the need to publicly address Chinese malign activity, including activity relating to the South China Sea, Taiwan and Xinjiang.

Leveraging Australia’s perspective

The Australian delegation comes to AUSMIN with certain geopolitical advantages. Australia is situated in and oriented fully towards the Indo-Pacific region in a way that the US, with its global reach and Euro-Atlantic alliances, is not. Australia’s undistracted focus on the Indo-Pacific lends knowledge, nuance and credibility to the viewpoints that Australian ministers present across the AUSMIN discussion table.

Played carefully, Canberra’s insider’s view of the Indo-Pacific could have synergistic effects on the soft-power advantages Washington still enjoys in the region, as shown by the US and Australia respectively ranking first and fifth for cultural influence in the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index 2021.

The change of government in Canberra also brings opportunity. Wong and Defence Minister Richard Marles approach their first AUSMIN able to show broad continuity with the robust China settings of the former government, but with room to try new things, such as on climate cooperation.

The case for strategic equilibrium

Wong has proposed ‘strategic equilibrium’ as the basis for Indo-Pacific order, blending realist elements such as alliances along with faith in the value of institutions and rules-based order, as these excerpts from her speeches in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore reveal:

[We seek] an order framed by a strategic equilibrium where countries are not forced to choose but can make their own sovereign choices, including about their alignments and partnerships.

[We seek a region] where disputes are guided by international law and norms, not by power and size … Achieving this requires a strategic equilibrium in the region.

If strategic equilibrium sounds vague, that’s probably somewhat deliberate—only a flexible concept with wide appeal can catalyse the diversity of countries we must engage across Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Those countries are sceptical of joining either formal alliances or values-based coalitions. They’ll be most receptive to a positive vision, backed by practical initiatives about which they have the sovereign choice whether and how to engage.

In addition, strategic equilibrium provides some helpful rhetorical distance from ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP)—the strategy masterminded by late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and adopted by the US and others. This distance is important, as some countries in the region, encouraged by Chinese propaganda, misinterpret FOIP as a shibboleth for containment or democracy promotion.

While Australia has effectively had an Indo-Pacific strategy since the foreign policy white paper in 2017, we’ve tended to avoid the FOIP moniker by fiddling with adjectives. For instance, the last AUSMIN joint statement advocated an ‘open, inclusive, and resilient Indo-Pacific’. By adopting strategic equilibrium, Australia has a more elegant alternative lexicon.

Therefore, Wong should reference strategic equilibrium at AUSMIN. The aim isn’t to persuade the US to adopt or amplify the term. It could be included in the joint statement and raised at the media conference, which would juxtapose Australia’s positive vision for the region alongside the necessary and robust language calling out Chinese conduct. This communicates Australian agency and leadership to an Indo-Pacific audience.

A prominent role for strategic equilibrium also reinforces the principle that foreign and defence policies are two sides of the same coin. The post–Cold War turn towards soft power and non-traditional concepts of security loosened our grip on the fact that foreign policy and diplomacy are at heart about war and peace. While the term is Wong’s, strategic equilibrium rests comfortably alongside Marles’s call for ‘an effective balance of military power’ at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June. To be effective, Australian foreign and defence policies must also be in equilibrium. Achieving that balance will make Australia’s voice more credible and respected in the region.

An opportunity to engage on indigenous diplomacy

Wong could use AUSMIN to highlight Australia’s indigenous diplomacy agenda and propose avenues for practical cooperation with the US in the region.

Wong emphasised First Nations perspectives in Australian foreign policy in her statement to the UN General Assembly in September. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s indigenous diplomacy agenda pre-dates the current Labor government, but Wong is elevating it by creating a new office of First Nations engagement, headed by an ambassador for First Nations peoples. To be effective, it will require adequate resourcing and a sense of mission that acknowledges both areas of common experience and the differences between indigenous peoples here and around the world.

There’s a place for the US in indigenous diplomacy. New Zealand, Canada and Taiwan are among the other countries elevating indigenous priorities in their foreign policies, including through the Indigenous Peoples Economic and Trade Cooperation Arrangement launched in Ottawa. The US State Department has held some consultations with indigenous groups already, but seemingly only in a domestic context. Over time, this is another area on which the US, Australia and others could cooperate with Taiwan, reinforcing Taipei’s space in international forums without contradicting one-China policies.

While indigenous diplomacy has domestic dimensions, it also promises to become a channel for delivering Australian foreign policy objectives, especially in the Pacific. The US has diverse indigenous communities, which include the Pacific islanders on Hawaii and the other US territories in the Pacific. The US also has a special relationship through the Compact of Free Association with the Marshall Islands, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia.

Wong could use AUSMIN to propose incorporating indigenous diplomacy into like-minded aid donor coordination meetings for the Pacific. In addition, Australia and the US could potentially both participate in an indigenous diplomacy side event at a Pacific forum.

Handling China and other thorny issues

Inevitably, China will be the organising principle behind the AUSMIN discussions because it’s the primary challenge facing both Australia and the US. Both countries’ approaches to China converge around what Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Wong have called ‘cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, and act in the national interest’, which aligns broadly with the US’s three ‘Cs’ of competition, cooperation, confrontation.

The thorniest issues in the AUSMIN joint statement relate to China, including calling out regional assertiveness in places like the South China Sea and the violation of human rights in Xinjiang, Tibet and elsewhere in China. Taiwan will require the most careful handling, and any change in language on Taiwan, even the number of words in the relevant paragraph, will be unpicked at length by commentators. Last year’s communiqué contained strong supportive language on maintaining the status quo relating to Taiwan, and cross-strait tensions have only increased since. Robust language on all these topics is essential—any backsliding would be noted by China and the region.

However, as both governments will already be aware, a focus on China shouldn’t drown out the positive message to the Indo-Pacific that’s the hallmark of a successful AUSMIN. Similar logic applies to other concerns, such as Myanmar and North Korea. There’ll be questions about China at the media conference of course, where it would be sensible to ensure coordinated but not identical responses on foreign and defence policy. Wong could affirm Australia’s agency over its China policy by referring to acting consistently in the national interest, while citing the homegrown concept of strategic equilibrium as the basis of regional engagement.

Behind closed doors, there’ll be much agreement on the scale and urgency of the China challenge. Commentators may speculate that the US side will seek reassurances that the recent revival of top-level Australia–China meetings, and what seem to have been mistaken remarks by Albanese on Taiwan and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, don’t equate to potential softening of Australia’s China policy. A strong communiqué will help assuage any lingering concerns. But channels of communication between Canberra and Washington are so attuned these days that such reassurance would also have been communicated well ahead of AUSMIN, reserving the precious time in meetings to mull more sensitive topics, such as Chinese intentions and regional contingencies.

In private meetings with US counterparts, Wong and Marles should seek assurances that the US is committed to strategic competition with China over the long term. Countries across the Indo-Pacific dislike great-power competition on their doorstep, but many fear the US’s absence and inconsistency even more.

To compete, the US must be persuaded to work with Australia and other allies and partners to expound a positive vision for the region, including a persuasive pathway to prosperity. In this regard, the Australian delegation should reiterate that the US’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership has ongoing and negative strategic implications. That might seem like wasted breath, as the US returning to the pact lies outside the Overton window for the foreseeable future. But political winds change and political muscle memory fades—it pays to keep this at the forefront of minds. For now, Australia and the US should put more flesh on the bones of the available alternatives, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework agreement.

The Chinese government’s online censorship regime isn’t new. It succeeded in ‘nail[ing] jello to the wall’, to use the words of former US president Bill Clinton, when the world thought the Chinese Communist Party wouldn’t be able to control the internet. The erection of the ‘great firewall’, the success in keeping out external sites and news, the intense surveillance of public and private online activities, and censorship and restriction of information are just a few different flavours of jello. But a recent protest in Beijing has shown that tech solutions are often not enough. Self-censorship is the ultimate form of information control the Chinese government is striving for, and Hong Kong is quickly falling victim to it.

Last month, just days before the CCP’s 20th national congress, a lone protester launched a rare display of political dissent in the capital armed with two simple handwritten banners he hung off a bridge. The first called for reforms, freedoms, elections, dignity and an end to the government’s strict ‘zero Covid’ policy. The second banner read: ‘Boycott schools, go on strikes, remove the dictator and national traitor Xi Jinping.’

Photos and videos of the protest quickly started spreading online but were immediately censored on Chinese social media. The words ‘Beijing’, ‘bridge’ and ‘Haidian’ (the district where the incident happened) were also censored. Related terms like ‘courage’, ‘Beijing banner’ and ‘warrior’ were blocked from searches on social media platforms. By the next day, netizens relied on phrases and hashtags like ‘I saw it’ (#我看到了#) to refer to the incident. They too were quickly deleted, and the posters’ accounts were suspended for violating the platform’s rules and regulations.

The repercussions were more serious for others. Some unlucky individuals who shared an image of the bridge protest had their Weibo or WeChat accounts banned permanently. This significantly affects Chinese residents, who rely on the apps for many digital services beyond communication, such as the health QR code and online subscriptions. The frustration has led hundreds of desperate users to write ‘confession letters’ on WeChat containing phrases like ‘I have profoundly realised my mistake’ and ‘I won’t let down the party and the country.’ Users begged Tencent, the company that owns WeChat, to give them a second chance by reinstating their accounts.

By wiping their digital identity, Beijing wants citizens to know the repercussions of speaking out. Placing censors in Chinese social media companies isn’t enough; users must be proactive in censoring the information they receive. Without self-censorship, the system would soon be overwhelmed and news would spread to the point of no return. For the system to work, people need to be aware of what content is shareable and be frightened of the consequences of sharing or receiving ‘prohibited’ content.

The current information environment in Hong Kong encapsulates this need. Once home to a rich communications flow and public expressions of dissent, Hong Kong has changed dramatically since the national security law came into effect in June 2020. Numerous local news outlets have been forced to close. Others still in operation either seek high-level approval before publishing or opt for self-censoring. Families and friends are now afraid to share or discuss sensitive content. Even receiving such content is considered dangerous, because having political information on one’s phone could cause trouble should the police gain access. Concerned for the safety of relatives and friends, many people overseas have stopped sharing sensitive content with close ones in Hong Kong. As a result, many people I spoke to in Hong Kong hadn’t heard anything about Beijing’s lone protester, a scenario that would have been unthinkable two years ago.

With limited independent news reporting, a restricted online environment and selective content being shared, free access to information is a thing of the past for Hong Kong residents. The only report of the bridge protest in the Chinese language, by the online news site HK01, was taken down after a few hours following an internal company meeting. Initium Media, which was founded in Hong Kong but is now based in Singapore, posted a widely circulated photo of the incident on Twitter. Hong Kong Free Press, an English-language news website, reported on the censorship around the protest a day later. No other Hong Kong media covered the incident.

If you’re a frequent user of Western social media sites and follow the right people, you may still have access to the news. But if all the people you’re surrounded by online aren’t receiving this information or are too afraid to pass it on, it doesn’t take much to find yourself living in an information-free bubble without even realising it.

Self-censorship is the consequence of anxiety and trauma inflicted by the Chinese government. The recent investigation into Chinese overseas police stations has shown extraterritoriality at work in dozens of countries and a worrying increase in transnational repression. Then there was the attack last month on Hong Kong protesters at the Chinese consulate in Manchester where an individual was dragged into the consulate grounds and beaten. Through actions like these, the PRC has created an environment of perpetual fear for dissidents and the diaspora community.

Online and in-person surveillance and punishment encourage self-censorship. Why put in the effort and resources to tackle the problem when the problem can be eliminated at its source?

Internationally, the Chinese government is pushing for self-censorship on foreign policy and human rights abuses in China. Through pressure, threats, inducement and coercion, many countries silence themselves out of fear of harming their interests or upsetting Beijing. There is no easy solution to self-censorship. We can call on dissenters to be more vocal, but then we are also asking them to overcome their fear of a repressive government and risk the dramatic consequences that might ensue.

As worldwide protests continue, Chinese people have shown that they also hold a diverse range of views, and, if given a chance, they won’t shy away from expressing them. Kathy, a Chinese student based in London, said she has found through protesting that ‘Courage needs practice, too. I won’t be able to learn these things unless I practise them constantly.’ A generation is waking to the potential of displaying dissatisfaction, and the courage and costs that come with it. As Louisa Lim described encouragingly in her book Indelible city, even when protesters lose everything in this dangerous game, the one thing that can’t be taken away is their ‘freedom of thought’.

The new leadership team selected by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the 20th national congress of the Chinese Communist Party failed to impress financial markets at home and abroad. In the week following the announcement of Xi’s new team, Hong Kong’s stock market declined by 8.3% and the Shanghai Composite Index, China’s largest stock exchange, dropped 4%, despite the Chinese government’s intervention to prop up prices. US-listed Chinese stocks plunged by 15%.

Investors have good reason to worry. Though financial markets had already priced in Xi’s third term, investors had hoped that he would appoint a team of more moderate, experienced officials capable of putting pragmatism above politics. Instead, Xi packed the Politburo and its standing committee with loyal allies and protégés.

China’s next premier will be Li Qiang, who was Xi’s chief of staff (2004–07), before later serving as governor of Zhejiang province (2013–16) and CCP secretary of Shanghai (2017–22). Li is widely credited with convincing Tesla to build its largest overseas factory in Shanghai—an achievement that has bolstered his business-friendly reputation. But, unlike every other premier since 1988, Li has no national-level administrative experience.

Ding Xuexiang, the next executive vice premier of the State Council, has even less leadership experience under his belt, having spent the last 10 years as Xi’s principal aide. In investors’ view, these officials lack the knowhow and independence to mount an effective response to the profound economic challenges China faces.

Xi stands to benefit from these low expectations, with any minor success appearing significant and burnishing his government’s credibility. Here, perhaps the lowest-hanging fruit is his zero-Covid policy, which has devastated the economy and contributed to an urban youth unemployment rate of nearly 20%.

At the party congress, Xi had little choice but to tout the policy as a major success, despite the devastation it has wrought. But with the meeting out of the way, and Xi starting his third term, the incentive to end the zero-Covid policy is strong. The boost to growth and employment—and to Li and Ding’s reputations—would be immediate.

Xi’s new economic team would also benefit from easing regulatory pressure on China’s technology sector. Since the Chinese government began tightening the regulatory screws, private tech companies such as Alibaba and Tencent have suffered, and foreign investors have fled China in droves. Goldman Sachs estimated last year that the crackdown had wiped out roughly US$3 trillion of the Chinese tech sector’s value.

Given that the tech crackdown is widely viewed as excessive and counterproductive, any letup by the government would send positive signals to investors about the future of China’s tech sector, the new leadership team’s pragmatism and the prospects for a return to robust economic growth.

But China’s new leaders can make the greatest impression on investors if they can prove that they can handle the country’s toughest economic challenge: an imploding real-estate sector. Property sales are likely to drop by as much as 30% this year. Several large developers, such as Evergrande and Shimao, have defaulted on their debt. With funding cut off, many building projects remain unfinished, leading some angry home-buyers to stop making mortgage payments.

This crisis will be the true test of the new economic team’s capabilities. Can they find a solution to widespread developer insolvency? Can they prevent the mass bankruptcy of local government financing vehicles, which took out massive bank loans using land as collateral? Can they find ways to ensure that new projects are not left unfinished? And can they stave off a housing-price collapse, as real-estate investment stops generating returns for the wealthy?

Even partial success here would bring a massive payoff. The real-estate sector powered China’s economy for two decades, contributing 17–29% of China’s GDP growth. Its revival could thus put the country back onto a positive growth path.

It’s far from clear that Xi’s new team is capable of devising effective solutions to the real-estate crisis; after all, their predecessors were not, despite being far more experienced. But even if they are, there is good reason to doubt that Xi will allow a change in policy. Simply put, whether the doomsayers are proved right or wrong depends—like virtually everything else in China nowadays—on the man at the top.