What are Australia’s options in a Taiwan contingency?

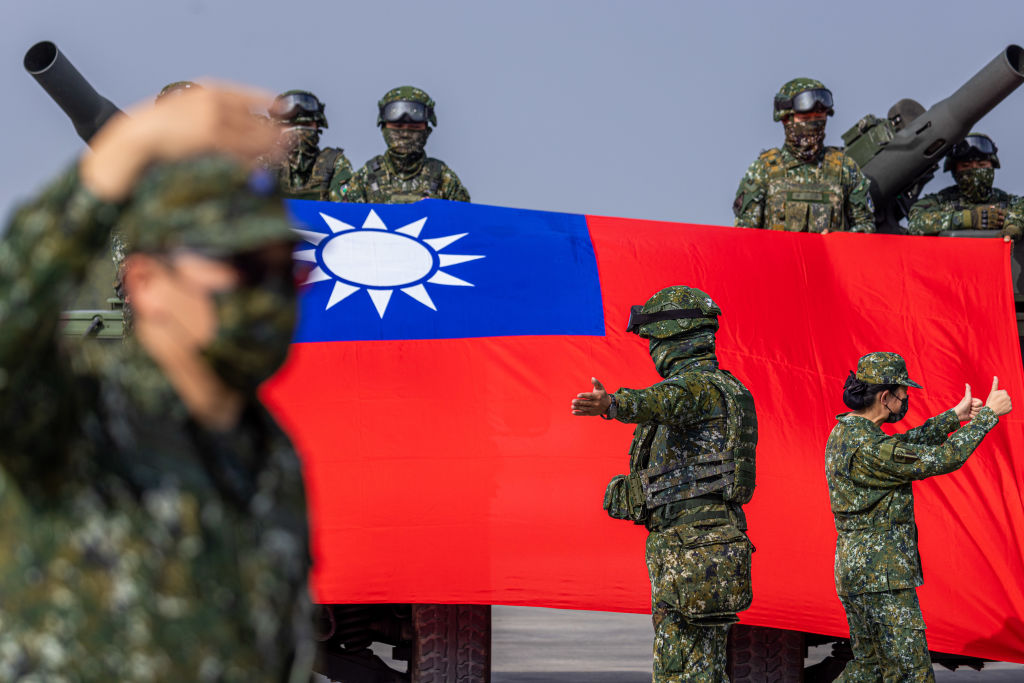

The president of Taiwan, Tsai Ing-wen, after visiting Taiwan’s few remaining diplomatic allies in Latin America, made a ‘stopover’ last week in California, where she met with US House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. Beijing responded with three days of military exercises, encircling Taiwan with hundreds of aircraft and ships.

It is another step forward in Beijing’s long-term tactic of normalising a military presence around Taiwan through opportunistic, systematic escalation. In Australia, this has come not long after the announcement of the details of Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS pact, which Beijing vociferously denounced.

These diplomatic and military activities have again focused the divisive national debate about relations with China on a question that’s been posed for decades: would Australia join the US in a war against China over Taiwan?

But Beijing’s military exercises around Taiwan should also serve as a reminder that Australia’s debate about China, the US and war involves a people we almost never hear from: the Taiwanese.

This is a very longstanding feature of Australia’s foreign and defence policy discourse. Leicester Webb, an august figure in the founding of the Australian National University who wrote the definitive account of the referendum to ban the Australian Communist Party, Communism and democracy in Australia, lamented in 1956 of Australia’s ‘tendency to think of the island simply as a pawn in the global chess game which is the cold war and to envisage solutions of the Taiwan “problem” which take account of everything except the actual situation on the island’. Webb said that ‘it seems necessary to insist that its inhabitants are entitled to be put in the foreground of the picture’.

Webb would recognise Australia’s conversation today and might note that it hasn’t moved forward much since the 1950s. What for him was a pawn in a global chess game has become today an underlying assumption that Taiwan can be treated as a proxy for US power in the region, as a sign of America’s waning primacy against a rising China.

For so-called hawks, this assumption makes for a very short and straight line from Chinese military action against Taiwan to Australia joining the US in a war with China. For those on the other side, it means that opposing the US alliance and opposing support for Taiwan’s defence are the same thing. The result is a very distorted debate that looks for truths not in the current realities of regional security but in perennial questions about Australian identity.

Needless to say, Taiwan is not just a proxy for US power. It is a real place. The war, if it comes, will be China’s war against the Taiwanese. In the absence of any viable roadmap to achieve the Chinese Communist Party’s goal of ‘unification’, war is the means through which Beijing would seek to annex the island and remake Taiwanese society in Beijing’s image.

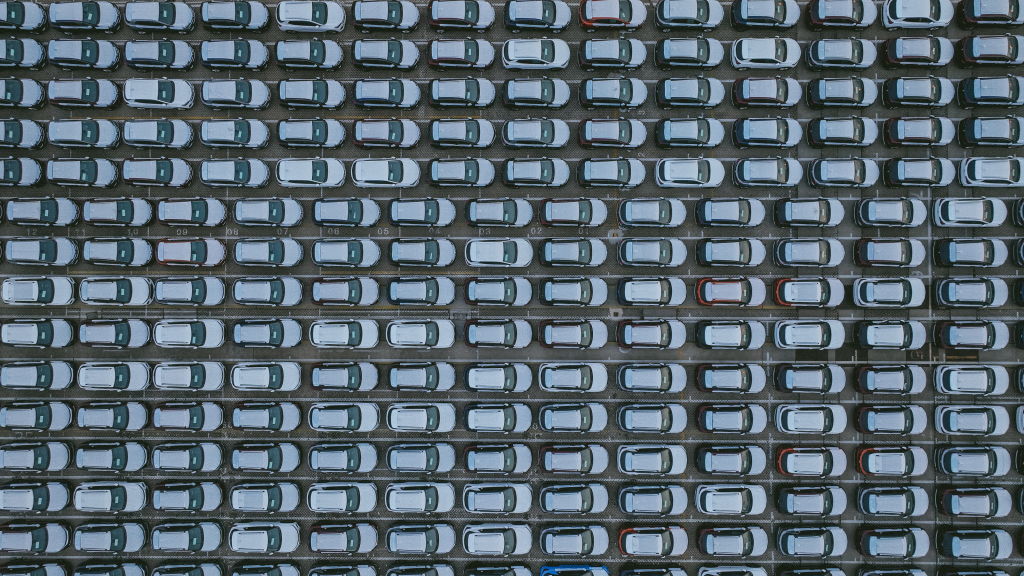

Rather than presenting a single choice about Australia’s commitment to the US alliance, Beijing’s Taiwan war would require a number of difficult, equivocal decisions. The direct economic consequences for Australia would be severe: Taiwan was our fourth largest export market in 2022 and is at the centre of global technology supply chains. But Australia would also have to decide whether to impose trade sanctions on China. We would face pressure from the US, Europe and Japan to do so, but our joining in would come at great economic cost to us as well as China.

Hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of Taiwanese would flee the conflict and Australia would need to decide how many to accept as political refugees. We would face pressure from the international community to accept many and from Beijing to accept none.

Beijing’s war would affect Australia through our relations with Japan, which has its own historical ties to Taiwan through its imperial history. It also prompts questions for Australia about our position on Taiwan’s own defence preparedness and diplomatic isolation.

And yes, in Beijing’s war, Australia would also have to decide whether to join the US in any military support for the Taiwanese in their defence of their island. Without international support, the Taiwanese would lose. As Tsai’s stopovers have shown, the US has a substantial policy and legal architecture with which it manages a close relationship with Taiwan, and its military involvement is probably inevitable. But far from being a short, straight line for Australia, a strategic goal of Beijing’s would be to keep Australia out of its war using military, political and economic means, all of which we would have to overcome to be involved.

If Beijing goes to war with the Taiwanese, it will cost Australia directly and dearly. The choice, then, is not about following along or not following along with the US. It is about whether we passively wait for Beijing to take that fateful action and try to bear its economic and humanitarian costs on us or whether we strengthen our means to act with power in the region in our interests. The government has presented a very expensive and not unproblematic plan to establish those means with the submarines to be delivered through AUKUS. There may be other, wiser, ones. But trying to isolate ourselves from Beijing’s actions is not a choice available to us.