Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The Chinese economy may be softening and commodity prices falling, but Australia’s exports to China hit a record $102.5 billion in the first half of this year thanks to massive shipments of lithium concentrate.

Lithium has overtaken liquefied natural gas as Australia’s second biggest export to China behind iron ore, with sales rocketing to $11.7 billion between January and June. Two years ago, first-half sales of lithium to China reached only $470 million.

China is taking almost all of Australia’s lithium output, underlining its dominance of both critical-minerals processing and of the energy transition more generally. Apart from China, just 2% goes to Belgium and 1% each to the United States and Korea, according to the Department of Industry, Science and Resources.

While the development of a major new export commodity is a boon to the economy, especially at a time when prices of other exports are sliding, China’s capture of the lithium market runs counter to the warning in the Australian government’s new critical minerals strategy of the danger of excessive reliance on a single customer.

The strategy declared that the ‘risks of disruption to critical mineral supply chains are heightened when mineral production or processing is concentrated in particular locations, facilities or companies’. Australia’s strategy was to work with ‘likeminded governments’ to diversify supply chains.

Detailed trade data from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade shows that the diversification of export markets during China’s two-year campaign of economic coercion of Australia was short-lived. Sales to most of Australia’s other principal trading partners have been falling sharply as sales to China recover.

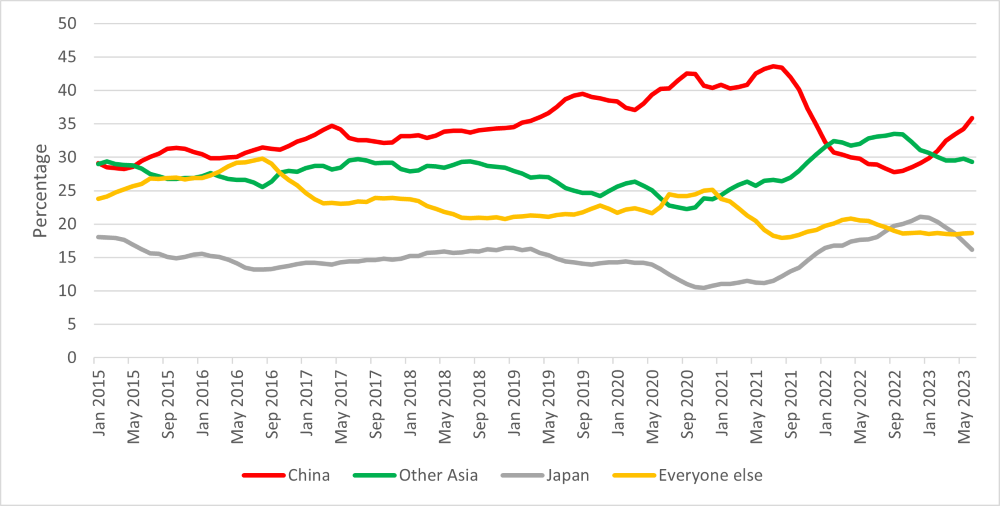

When China embarked on its campaign of economic coercion, Australia was saved by its other Asian trading partners (see chart below). China’s share of Australia’s exports had peaked at 43% in May 2020 but plunged to 28% by the middle of last year.

Shares of Australia’s export markets, January 2015 to June 2023

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (six-month rolling total).

The slack was picked up by Japan, whose share of Australia’s exports went from 11% in mid-2020 to 21% by September last year, and by other Asian nations whose combined share rose from 22% to 34%, comfortably overtaking China.

But with China’s share climbing back to 36% in the first half of this year, Japan’s share has dropped back to 16% and the rest of Asia is now taking just 29%.

Australian coal sales to China stopped entirely during 2021 and 2022, causing huge shifts in the global coal trade. China started buying coal from Indonesia, which then cut its sales to India and elsewhere. India boosted its purchases of Australian coal that had previously gone to China.

These flows have now reversed. India’s purchases of Australian coal, for example, went from around $1.5 billion a month to $2.5 billion a month through much of last year, but are now back to about $1.3 billion. China is now spending about $1 billion a month on Australian coal.

China has also returned to purchasing Australian oil, with sales rising from nothing to $860 million in the first half of the year. Although never put on China’s list of banned Australian purchases, imports of wheat and other cereals (excluding barley) have risen rapidly from $500 million in the first half of 2021 to $3.1 billion so far this year.

The trade figures to the end of June don’t show any Australian exports of barley, for which China has only just agreed to drop its punitive tariffs. Tariffs remain on wine, and at the end of June, China still had trade bans on Australian copper ores, wood chips, timber and crayfish.

Total Australian exports to China rose by 22.4% in the first half of the year, despite a sharp, and continuing, fall in commodity prices.

China’s capture of Australia’s lithium exports highlights the tension between economic forces and strategic policy. The government favours investment from Western nations and its clear preference is to build supply chains with Western partners that bypass China.

The Foreign Investment Review Board has been knocking back efforts by Chinese companies to invest in the Australian critical-minerals industry. For example, it has vetoed moves by a company directed by a Chinese national, Astroid Australia, to purchase 90% of lithium miner Alita Resources and prevented Yuxiao Fund from increasing its 9.9% stake in rare-earths miner Northern Minerals.

However, China has been building its expertise in critical minerals since the 1980s. Its unrivalled lead in processing and manufacturing technology makes it the obvious choice for buyers wanting quality refined critical minerals.

More broadly, the concentration of export markets in China exposes Australia to the impacts of both downturns in the Chinese economy and future geopolitical tensions between the two countries. However, the experience of the past two years, when the Australian economy barely noticed the impact of China’s trade strikes, underlines the flexibility and adaptability of international markets.

Thousands of tonnes of grain stored in the Ukrainian port of Odessa were destined for some of the world’s hungriest people. But on 17 July, Russian President Vladimir Putin nixed Russia’s participation in the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI), a UN- and Turkey-brokered agreement that promised safe passage of the grain through the Black Sea to global markets.

Russia may have a war interest in blocking Ukraine’s grain but its partner, China, is likely to push for a new grain deal. Russia’s actions clash with China’s longstanding practice of courting countries in the global south, and Beijing will hesitate to side with Russia in devastating their food security. How China brokers such a deal will reveal the limits of the Russia–China relationship.

Despite the war, Ukraine remains one of the world’s largest wheat suppliers. As of July, it provided 80% of the World Food Programme’s wheat, and the UN estimates that 64% of the grain Ukraine exported under the BSGI went to low- and middle-income countries. The International Monetary Fund forecasts a 10% to 15% increase in global grain prices from the deal’s cancellation, while wheat and corn futures have risen by 9% and 8%, respectively. Without a deal, the world’s poorest people will go hungry, increasing the risk of conflict, economic privation and disaster-driven migration.

There’s a clear incentive for China to involve itself in repairing the BSGI. Standing by Russia’s actions could destroy its decades-long diplomatic strategy of strengthening bilateral relations with developing countries. It has increased its engagement and leadership of the global south through forums such as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and the African Union, and promised infrastructure, aid and security through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Beijing has presented itself as a benevolent supporter of the global south’s rights to development, prosperity, peace and food security.

These efforts have been embedded in Chinese messaging for years. Every BRICS declaration for the last five years has referenced them as China has touted the grouping as an alternative to the Western-led multilateral system. Food security was further enshrined as a pillar of BRICS through the 2022 BRICS strategy on food security cooperation and the BRICS Forum on Agriculture and Rural Development.

China will also look for any opportunity to increase its influence and voice within the UN, a broker of the BSGI. Chinese state media has focused on China’s work in ‘establishing peace’ in Ukraine through the UN, through bilateral diplomacy and by reporting neutrally on the UN statement condemning the breakup of the deal. Qu Dongyu, a Chinese national, is director-general of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization and on 22 July, Geng Shuang, China’s deputy permanent representative to the UN, told a Security Council briefing that China wanted a resolution to the halting of the BSGI, noting that it was of great significance to ensuring global food supply. This suggests that China sees promoting food security as important to its international interests.

In China, Russia has a begrudging partner that seesaws between tacit support of the invasion and diplomatic messaging pitching itself as a peacemaker while noting how horrified it is at ‘NATO’s eastward expansion’. Its suspected direct support for Russia’s war is further enflaming tensions with the US but, more importantly for China, harming its reputation and economy. Several European countries that were previously strong BRI supporters have said they won’t attend China’s BRI forum later this year because Russian President Vladimir Putin will be there. China wants and needs friends, and Russia is making that tougher than it needs to be.

In addition, China knows that both the Western coalition and Russia’s proposed solutions to the impasse won’t adequately secure food supplies to the global south.

At its poorly attended Russia–Africa summit in late July , Moscow pledged free grain to a group of six African nations. This misses the point that the ability of poor countries to buy grain at reasonable prices is determined by supply, not the identity of the buyers and sellers. It also ignores that short-term deals with no promises of renewal are unlikely to calm markets. With only six nations offered the deal, Putin politicised a food security decision in a way that was unlikely to win him friends among economies that missed out.

NATO and Ukraine, on the other hand, favour a diplomatic solution to the problem and have proposed logistical workarounds to export Ukrainian grain west over land or south via the Danube delta. Although this would address grain supply, insurance premiums and the costs of transporting goods overland from zones under Russian shelling would limit its impact on prices—especially since the European Commission said in late July it has no budget to subsidise shipments.

Given all this, analysts should watch for increased Chinese messaging efforts bilaterally, multilaterally and through state media burnishing China’s credentials as a benevolent leader of the global south. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, announced at a BRICS ministerial meeting on national security on 25 July ‘four propositions’ for strengthening cooperation among the nations of the global south that could be a basis for this. There will likely be an uptick in bilateral meetings with affected countries in Africa and the Middle East as well as with Turkey to gain intelligence on, and perhaps shape, that country’s position on the BGSI. Crucially, analysts should watch for possible Chinese diplomatic efforts to convince Russia to sign back onto the deal or negotiate alternatives.

Ukraine’s grain harvest occurs in August and September, and a deal is needed urgently for this year’s grain to be exported. The BRICS summit in South Africa that begins on Tuesday would be an ideal opportunity for China to pressure Russia, and perhaps even to announce a deal. Its details will reveal the extent of China’s strength in its relationship with Russia and the health of its foreign affairs apparatus. Whatever happens, we should hope for the sake of the world’s poor that a deal is struck to let the grain flow.

Last month, Canada suddenly announced that it was freezing all ties with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a multilateral lender created by China as an alternative to the World Bank. According to Canada’s finance minister, Chrystia Freeland, the decision was in response to allegations that China’s government had stacked the institution with Chinese Communist Party officials who ‘operate like an internal secret police’.

Then, just days later, Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto announced that the Chinese company Huayou Cobalt would site its first European factory in Hungary, in the small village of Acs, where it will produce cathode materials for electric-vehicle batteries.

Against the backdrop of the US–China rivalry, it’s easy to dismiss these two events as trivial. But Canada’s and Hungary’s leanings are highly relevant to this bigger geopolitical story. While decision-making in Washington and Beijing obviously matters, these strategic bets by smaller countries offer equally important insights into the future of globalisation.

Canada and Hungary are among NATO’s less populous member states. And with each undergoing a fundamental change to its strategic outlook, the two countries are somewhat unexpectedly beginning to trade places. Five years ago, Hungary was the poster child of nationalism, and Canada a paragon of free-trading globalisation. But now, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and his political director, Balazs Orban (no relation), are betting on a strategy of economic connectivity, whereas Canada is heading in the opposite direction.

Faced with all the talk of protectionism, decoupling and China’s notion of economically self-sufficient ‘dual circulation’, Balazs contends that, ‘if the fragmented, bloc-based international order of the cold war era is restored, it will threaten Hungary’s international relations and trade status’. For a country whose economic model relies on trade with both Germany and China, and on oil and gas from Russia, decoupling is bad news. Thus, the ‘Orban doctrine’ is about finding a sweet spot between China and the United States, rather than choosing one over the other.

Canada, on the other hand, used to be a standard-bearer for multilateralism and the liberal international order. But it now seems to have abandoned the idea of a universalist order in favour of one that excludes states motivated by values that depart from its own. The most articulate exponent of this strategy is Freeland, the veteran journalist who is now Canada’s deputy prime minister and finance minister. While US Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen coined the term ‘friend-shoring’ to describe the privileging of trade relations with countries that hold similar values, Freeland has taken the concept much further, advocating not just deeper economic relations with like-minded countries, but closer social and political ties as well.

According to the ‘Freeland doctrine’, the West should no longer be devoting time and energy to slowing the unravelling of the geopolitical era that began after the Cold War. Instead, it should start severing ties with autocracies and concentrating more on forming smaller like-minded groupings such as the G7.

This is not just empty talk. Both Hungary and Canada have already started implementing their new agendas. In addition to approving the Huayou factory, Hungary has also greenlit the Chinese company CATL’s plan to build what will be the biggest battery plant in Europe. In doing so, it is making a big bet on the future of China’s economic relations with the European Union.

Of course, Canada and Hungary have very little influence on the shape of the global order. But when it comes to reacting to the structural changes that are underway, they have given other small and mid-sized countries two radically different models to consider. The extent to which one proves more attractive than the other will have far-reaching implications.

One of the biggest question marks hangs over the rest of the EU, with its population of nearly 500 million and combined GDP of US$16 trillion. Germany, especially, will have to make strategic choices that will inevitably pull the rest of the bloc along with it.

There were high hopes that Germany’s eagerly anticipated China strategy, published earlier this month, would provide some clues as to whether it’s heading down the Canadian or the Hungarian path. Yet the months-long drafting process culminated in a document that tries to have it both ways, embracing Freeland’s grammar and Orban’s logic.

The German strategy begins with the clear-eyed observations that ‘China has changed’ and that ‘de-risking is urgently needed’. Yet it stops far short of advocating decoupling, and it leaves it to German companies—with their deep economic interests in China—to decide how much de-risking is appropriate. This is quite a departure from an earlier draft of the strategy, which had envisioned ‘stress tests’ on German companies present in China and would have required German businesses to ‘specify and summarise [their] China-related developments’. That’s no small matter, considering that just four German companies—Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen and BASF—accounted for 34% of all European investment in China between 2018 and 2021.

Notwithstanding the new strategy document, German politics remains divided between the two different persuasions. Events in both China and the US will undoubtedly bear on the debate and help to determine which faction wins out. The stakes are high, because where Germany goes, the rest of Europe often follows. While its ambivalent rhetoric tells us very little, its policy decisions will tell us everything. We will soon know which path it has chosen.

Recent strident assertions by former Australian prime minister Paul Keating that NATO has no place in Asia and should limit itself to Europe and the Atlantic and not try to expand into the Asia–Pacific are misjudged and should not be allowed to pass unchallenged.

With global commerce and security interests more interconnected than ever, NATO, the world’s premier political-military alliance, and one of the most successful collective security enterprises in history, understands that developments in the Indo-Pacific region are highly relevant to global cooperative security.

Regional and collective defence commitments will always be paramount for NATO but cannot be its defining perspective in an increasingly globalised, interconnected and uncertain world. NATO’s interests do not stop at the Tropic of Cancer in the Atlantic. Contrary to the views of Keating, NATO has a vital interest in a stable Indo-Pacific region, including unhindered lines of communication on, under and above the region’s oceans and seas. This was reaffirmed at the recent NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, where the alliance’s 31 member states agreed that what happens in the Indo-Pacific matters for Europe and therefore for NATO. And, conversely, what happens in Europe matters for Indo-Pacific nations.

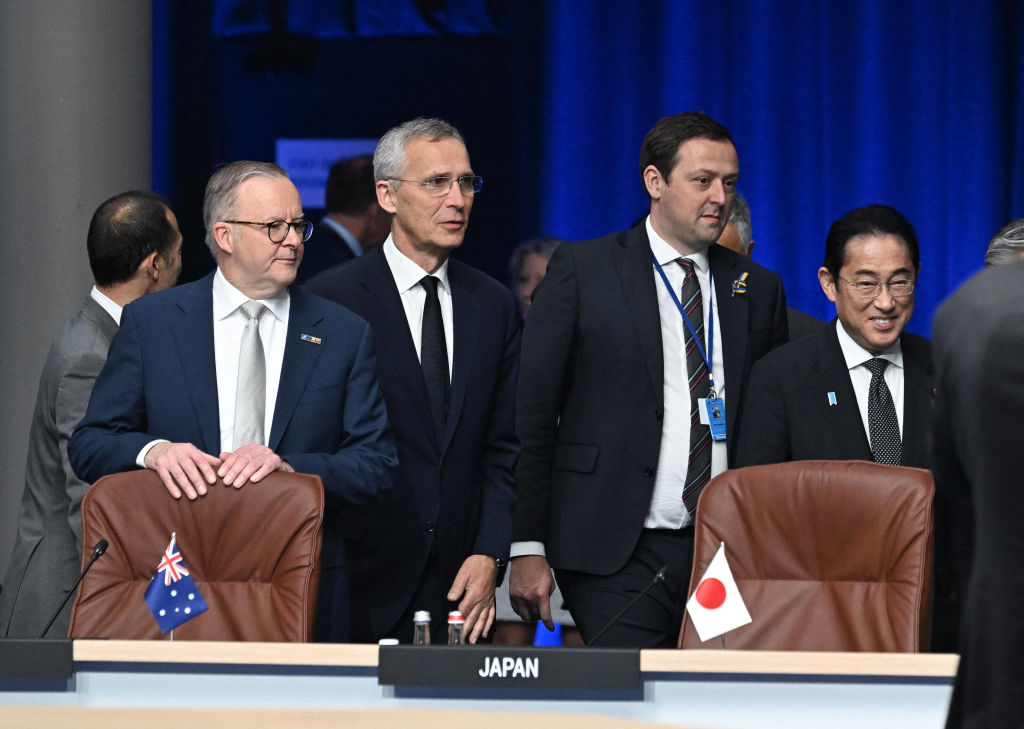

Over the past decade, the centre of world power has been shifting from Europe to the Indo-Pacific region. Taking this into account, NATO, which includes three Pacific Rim members—the US, Canada and France—is considering the substance and direction of its regional interests and bilateral cooperative security relationships with its four Asia–Pacific partners. Similarly, these partners—Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea—are considering the best way in which they might each interact and cooperate with NATO, cognisant of their unique geographic and strategic environments. This doesn’t translate into expanding NATO membership and collective defence into the Indo-Pacific. It does, however, need to manifest itself in clear and precise bilateral partnership objectives, opportunities and engagement.

The global maritime trading system, in particular, is one that no one owns but all benefit from. The impact of trade, containerisation and just-in-time supply chains means that good order at sea in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, including the South China Sea, is just as important to NATO members as the security of trade and shipping in the Atlantic and Mediterranean is to Indo-Pacific nations, including China. It is a system that can only work effectively if there is a strong and determined cooperative and collaborative rules-based international effort to keep the global commons functioning. It is an area where the geostrategic interests of NATO and its Indo-Pacific partners increasingly intersect.

Importantly, the rise in wealth and defence expenditure in the Indo-Pacific is occurring in midst of numerous simmering and unresolved maritime territorial claims, disputes and nuclear crises in the region, including China’s threats over Taiwan and its territorial claims and belligerence in the South China Sea. NATO is not immune from such developments and will not have the luxury to choose the future strategic challenges it will face.

The NATO summit in Vilnius highlighted the growing consensus among NATO members and Asian democracies that China’s increasing power and territorial ambitions pose a significant challenge to global security. The summit’s communiqué criticised China’s ‘coercive policies’ and attempts to ‘subvert the rules-based international order’. While NATO’s focus has traditionally been on Russia, the communiqué’s emphasis on China indicates a significant sharpening of focus. The statement also highlighted China’s attempts to control key sectors, infrastructure and supply chains, and to create strategic dependencies. It did, however, emphasise the importance of constructive engagement with China.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese stated—rightly, in my view—that democracy, not geography, should define a nation’s interests. At the NATO summit, he argued that the struggle between democracy and autocracy is being fought in the Indo-Pacific, with China as a key antagonist. He claimed that China is modernising its military without transparency or assurance about its strategic intent. Speaking to NATO leaders, Albanese said Australia was under pressure from China, but the government’s response was principled and level-headed. He added that Australia would cooperate with China where possible, but would also disagree where necessary and always act in its national interest.

UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace, meanwhile, has warned that the West must develop a more coherent political strategy towards China’s expansionist activities in the South China Sea or face a conflict within a decade. In a recent interview with the Sunday Times, Wallace said that China’s aim of constructing new islands and stationing military equipment in the region could lead to a ‘total breakdown of politics in the Pacific’.

While we live in a multipolar world, it is clear that the Indo-Pacific is becoming the stage of intensifying strategic competition—not only military or economic competition, but competing visions for the global order. Above all, the relationship between the United States, the leading member of NATO and a significant Pacific power in its own right, and a rising, prosperous and increasingly confident, assertive and coercive China will, more than any other, determine the outlook for international security and prosperity. Strategic competition between the US and China is a reality, but both should actively seek stability, not conflict, and that should be encouraged by NATO and its partners in the region.

The Chinese Communist Party has a long history of engagement with criminal organisations and proxies to achieve its strategic objectives. This article provides new evidence of the development of a CCP-linked influence-for-hire industry operating in Southeast Asia. This activity involves the Chinese government’s spreading of influence and disinformation campaigns using fake personas and inauthentic accounts on social media that are linked to transnational criminal organisations.

To investigate how the CCP is creating or acquiring inauthentic accounts for use in its influence operations, including those currently targeting Australia, ASPI traced some of them to a network of Twitter accounts advertising links to Warner International Casino (华纳国际赌场), an illegal online gambling platform operating out of Southeast Asia and linked to Chinese transnational criminal organisations.

ASPI’s first report on coordinated information operations linked to the Chinese government, published in 2019, found that the campaign against the Hong Kong protests used repurposed spam or marketing accounts, which were used by CCP operators to replenish their covert networks. Those personas are typically unconvincing but are cheap, created en masse and quickly adapt to avoid automated spam-detection systems. They are partly why Chinese government entities are thwarting social media platforms’ latest efforts to counter influence operations and other coordinated inauthentic behaviour.

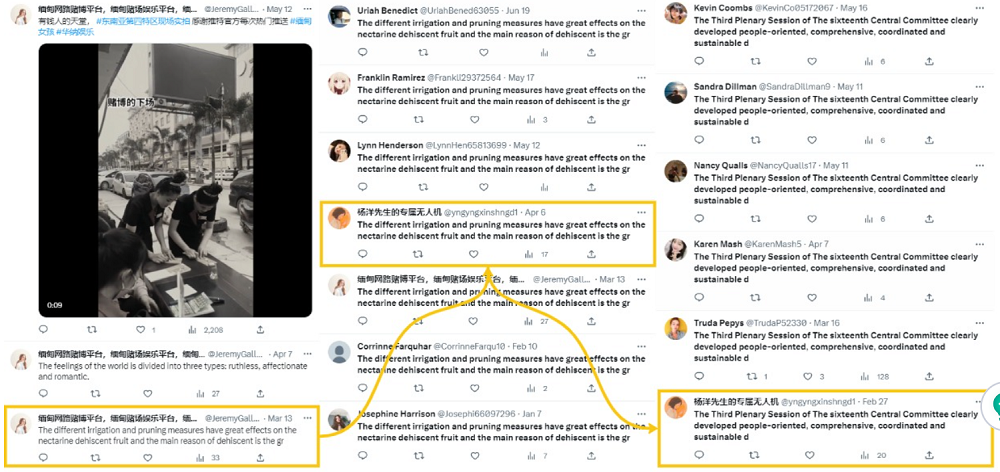

In the recent campaigns targeting Australian political discourse discussed in the first part of this report, many of the accounts impersonating and targeting ASPI use Bored Ape Yacht Club images as profiles. Those profiles are popular across many spam networks related to NFTs (non-fungible tokens), but they’re also used by multiple accounts posting links to Warner International (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A CCP-linked account targeting ASPI with a Bored Ape profile (left) and a Twitter account mostly promoting Warner International with a Bored Ape profile (right)

Likewise, accounts promoting Warner International are using similar AI-generated profile images on inauthentic accounts involved in CCP influence operations. A Twitter account named ‘Cassandra Anderson’ has a profile image that appears to have been generated by ‘This Artwork Does not Exist’ and matches other similar AI-generated artworks used as profile images by accounts previously linked to the CCP (Figure 2).

Figure 2: CCP-linked accounts with AI-generated profiles claiming that the US is an irresponsible cyber actor (left) and a Twitter account promoting Warner International (right)

At times, the same images are used by both CCP-linked accounts and accounts promoting Warner International. The Twitter account of ‘Neda’ is involved in a CCP-linked online campaign that seeks to interfere in the Australian political discourse (including through ongoing heavy use of the #QandA and #auspol hashtags), such as by amplifying claims about sexual abuse in Australia’s parliament. This account shares the same profile image and cover photo as another Twitter account advertising Warner International, which has since been suspended (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A CCP-linked account interfering in Australian political discourse (left) and a Twitter account promoting Warner International (right)

In addition to having similar profile images, these accounts behave in the same way and likely belonged to the same pool of accounts when they were created. The Twitter account with the handle ‘JeremyGallache6’ is a representative example of this group. It was created in March 2023 and the bio links to Warner International. The account’s first tweet is cut off mid-word and appears to have been automatically translated from Mandarin. The text of that tweet is replicated by dozens of other accounts with similar profile images as their first tweets, which have also posted CCP propaganda (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Twitter timeline of ‘JeremyGallache6’ promoting Warner International (left) next to a list of accounts replicating JeremyGallache6’s first tweet (middle), including ‘yngyngxinshngd1’, which has posted CCP propaganda replicated by other similar accounts (right)

Another example is ‘Belinda Anderson’, who says that Falun Gong, a persecuted religious organisation in China, ‘should not appear’ and is a ‘cult’. ‘Belinda’ belongs to a group of accounts promoting Warner International that all have the same first few tweets. In the past year, accounts likely linked to Chinese police officers have displayed similar posting patterns. ‘Avery Alfred’, a CCP-linked account, joined Twitter in March 2023. Its first tweet is replicated by dozens of other accounts with similar profile images (Figure 5), like the accounts promoting Warner International.

Figure 5: Profile images of four accounts posting links to Warner International (left) and profile images of four accounts linked to CCP covert influence operations targeting Australia (right)

Warner International Casino appears to be associated with a casino owned by the Warner Company and based in the city of Laukkaing in northern Myanmar near the border with Yunnan Province, China. Twitter accounts posting links to its online gambling platform share the same logo as the Warner Company (Figure 6), and videos of the gaming room shared online match the images on Warner International Hotel’s website.

Figure 6: A Twitter account posting videos filmed inside Warner International (left), an image of the casino on the gambling website that was shared by Warner International Twitter accounts (middle) and an image of the casino on Warner International Hotel’s official website (right)

Warner International is a typical illegal online gambling platform that lures Chinese-language speakers inside and outside of China. Online users of the website place bets through a live broadcast of the casino and share the same gaming table as in-person gamblers.

On Reddit, accounts promoting links to Warner International post misleading explanations when the website stops its online users from withdrawing money from the platform. The number of such posts suggests that the users are often locked out of their accounts and lose access to their winnings and initial deposits. The accounts also offer counter ‘hacking technical teams’ when users’ online gambling accounts are supposedly ‘hacked’. These types of services have been reported to be secondary scams.

Chinese police officers are aware of Warner International’s operations. A 2021 Beijing Daily article revealed that officers from the Mudanjiang City Public Security Bureau in China’s northernmost province were investigating and arresting affiliates involved with Warner International’s gambling website (Figure 7). The article suggested that Warner International was operated by overseas gang members who were smuggling Chinese citizens into Myanmar to participate in illegal gambling or to work at the casino and entice other Chinese citizens to gamble online.

Figure 7: Screenshot provided in an article posted by Ningbo Police

There are a number of possible explanations for this development. It’s conceivable, for example, that elements of China’s security services are opportunistically acquiring inauthentic accounts from criminal networks, such as Warner International, to reinforce their covert influence operations online. The CCP has a history of engaging with criminal organisations, including triads in Hong Kong and Macau, to attain its political goals. For example, the head of China’s Ministry of Public Security, Tao Siju, said in 1993 that, as long as triads in Hong Kong were ‘patriotic’, the ministry should ‘unite with them’ to uphold Hong Kong’s prosperity following its handover from the UK government. That statement was coincidentally made a few days after a new nightclub called Top Ten had opened in Beijing. The club was co-owned by Tao and Charles Hueng, the head of the Sun Yee On triad, illustrating the links between senior security officials and prominent criminal figures.

More recently, Chinese high rollers linked to reported underworld figures have been entwined in alleged foreign interference operations in Australia operating out of casinos. Likewise, Warner International is one of many that have been reported to be bases for illegal online gambling and scam operations, including the Jinshui compound—a complex implicated in reports detailing online scams and gambling operations (which has also been linked to Cambodian officials, CCP United Front–affiliated figures and Suncity Group).

But it’s also possible, for example, that what we’re seeing here is an overlap in the outsourcing (of private contractors) being done between China’s security services, which need to maintain their global information operations, and those groups using inauthentic accounts to promote criminal networks, such as Warner International. While not exactly the same, there are similarities in what US-based news media outlet ProPublica unearthed in 2020 regarding a Beijing-based internet marketing company, OneSight Beijing Technology, which it found had ties to the Chinese government and was involved in covert influence operations on social media. ProPublica’s examination of an interlocking group of accounts linked to OneSight Beijing Technology found that some were impersonating the US government–funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia. We observed the same tactic in the recent campaign targeting ASPI, Safeguard Defenders, Badiucao, Vicky Xu and others.

The Chinese government is expanding its digital infrastructure to conduct online covert influence operations outside of mainland China, so such developments would also be consistent with behaviours that some social media platforms are seeing. For example, Twitter’s notes to its Moderation Research Consortium in 2022 said that technical indicators of a pro-CCP network suggested that it was being operated from Singapore and Hong Kong.

We know that the Ministry of Public Security is one of the primary agencies in China responsible for covertly manipulating global public opinion on social media. In scaling up its influence operations by purchasing inauthentic social media accounts from criminal networks, using such accounts, or both, it is enabling other criminal activities, such as illegal gambling, human trafficking and telecommunication crimes.

There are many things the Australian government should be doing to counter this malicious activity. Just as cybersecurity, particularly to combat intellectual property theft for commercial gain, was made a bilateral issue by Australia, so should this issue of cyber-enabled foreign interference.

The Australian Federal Police, for example, needs to raise the issue of foreign interference targeting Australian citizens and organisations, including bounties placed on Australian residents for exercising freedom of speech, with its counterparts in China during their law-enforcement working groups. The AFP should also consider these developments in the light of its necessary but increasingly complicated intelligence-sharing relationship with the Ministry of Public Security.

Government agencies, investigative journalists and civil-society organisations around the world have an important role to play in investigating this criminal–state nexus further and raising public awareness about such malicious regional activity. This is an opportunity for global law enforcement agencies, including Interpol, to increase their collaboration with local authorities to tackle cyber-enabled financial crime, human trafficking and corruption in the region.

In addition, governments and regional bodies need to apply greater international pressure on Cambodia and Myanmar to crack down on these types of activities. Governments should coordinate joint Magnitsky-style sanctions to target key figures in Chinese transnational criminal organisations and the political elites in those countries affiliated with, for example, cyber-slave compounds, which are becoming more common in the region. By disrupting those criminal operations, governments would also be combating an industry that’s spawning inauthentic accounts for states to peddle propaganda and disinformation.

The growth of a regional, criminal and state-linked influence-for-hire industry is yet another challenge for the Indo-Pacific, which needs strategies and new mechanisms to counter and deter the increase in hybrid activity in the region. Establishing an Indo-Pacific hybrid threats centre, similar to Europe’s equivalent (the Hybrid Threats Centre of Excellence in Finland), would help to build regional capacity, coordinate responses and enhance regional stability.

The threats we face as a society are no longer limited to violence, espionage and interference conducted in person—whether by individuals, state entities or criminal groups—but are increasingly enabled by digital personas, inauthentic accounts and coordinated networks that can reach anyone globally and instantly. AI experts have been warning governments to prepare for the impact that AI will have in supercharging disinformation and cyber-enabled interference. The question for policymakers will increasingly be about how they counter malign actors that are difficult to attribute or distinguish from legitimate actors online—especially when those actors operate across a booming ecosystem of digital platforms headquartered in different countries. This question will become harder and harder to answer without the right rules and legislation in place.

Once again, the solution is not passivity or silence. The Australian government’s current approach will not hold as we enter an era in which we need to protect our democratic institutions and our public discourse from cyber-enabled foreign interference in what will soon be an AI-saturated world.

Like many small and middle powers, Bangladesh is hedging its approach to great-power competition in the Indo-Pacific. Despite the release of its first Indo-Pacific outlook in April, Bangladesh continues to shy away from the traditional security issues that are fundamental to furthering the US-led rules-based order.

However, the document provides a promising starting point for the US and partners such as Australia. Supporting Bangladesh to achieve its economic and non-traditional security objectives will further the pursuit of a free and open Indo-Pacific and help to consolidate trust between Dhaka and Washington.

The release of the outlook comes in the context of repeated efforts by the US and others to persuade Bangladesh to join them in promoting a ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific. Bangladesh’s geostrategic location between China and the Indian Ocean region has prompted a steady series of visits from US officials, such as Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs Donald Lu in January. Bilateral visits with US partners have similarly increased in pace. In March, the UK’s Indo-Pacific minister, Anne-Marie Trevelyan, travelled to Bangladesh for the first time, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida noted in a speech that tapping into the economic potential of Bangladesh aligns with the principle of ‘excluding no one’ in the region.

In this context, the outlook has been perceived by some as a crystallisation of Dhaka’s regional positioning with respect to US–China competition. The document’s release right before Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s 15-day trination tour of Japan, the US and the UK has lent support to this climate of optimism. Although Hasina’s trip included a diverse range of engagements beyond security issues, it could indicate Bangladesh’s desire to engage further with advocates for a free and open Indo-Pacific.

But a closer look at the document’s substance tells a less rosy story. Aside from non-traditional security concerns, the outlook focuses on bolstering Bangladesh’s economic security. One of the objectives set out in the policy is ‘unimpeded and free flow of commerce in the Indo-Pacific’. The focus on prosperity is unsurprising considering Bangladesh’s recent economic growth. The country is on track to graduate from the UN’s list of least developed countries in 2026—and according to the outlook’s first paragraph, Bangladesh wants to become a ‘modern, knowledge-based developed country by 2041’.

But for the US and its partners, Bangladesh’s pursuit of prosperity is complicated by its adherence to a foreign policy of non-alignment. The outlook’s first guiding principle is ‘friendship towards all, malice toward none’. The Bangladeshi Foreign Minister A.K. Abdul Momen reiterated that sentiment following the launch of the document: ‘We are not following anyone. Our IPO is independent’.

One consequence of Bangladesh’s approach of neutrality is close economic engagement with both China and the US. The China–Bangladesh economic relationship has grown significantly, facilitated by its elevation to a strategic partnership of cooperation in 2016 and Bangladesh’s participation in projects under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), such as the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Economic Corridor. As the US seeks to embed Bangladesh more deeply in its sphere of Indo-Pacific influence, Bangladesh’s close relationship with China will be a significant barrier.

Another inhibiting factor for cooperation is Bangladesh’s lack of an underlying plan to achieve each of the 15 objectives under the outlook. As its name indicates, it is an ‘outlook’ rather than a ‘strategy’ or ‘policy’, and while it articulates the importance of the ‘exercise of freedom of navigation and overflight’ in the region, it establishes no meaningful pathway to achieving that.

With the outlook as a starting point, the US and its partners must work with Bangladesh towards its goals for the collective benefit of the Indo-Pacific. Bangladesh’s desire to engage with both China and the US makes work in areas of traditional security difficult, but Washington and its partners can still assist Bangladesh with the non-traditional security concerns the outlook identifies—including transnational crime, food insecurity and climate change.

Between 1976 and 2019, Bangladesh experienced an average temperature rise of 0.5°C, leading to well-documented impacts including cyclones and floods. Although climate-induced migration is typically internal, interstate migration will increase as the effects of climate change escalate. Deeper engagement with Bangladesh on issues like climate change could help prevent Bangladesh’s entrenchment in China’s sphere of influence.

Despite Bangladesh’s participation in the BRI, Hasina and her government have shown hesitation about the initiative’s future utility. Dhaka is concerned about its mounting debts to Beijing and issues with Sri Lanka’s and Pakistan’s BRI projects. In this precarious moment for Chinese credibility, the US and its partners can step in to provide Bangladesh with alternatives to Chinese investment.

Bangladesh will naturally continue to hedge, but the US and its partners can still deepen cooperation in line with the outlook where possible. This opportunity makes it a welcome regional mechanism for advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific, despite its limitations.

Australia is facing the largest challenge to its position of strategic primacy in the South Pacific since World War II as China continues to build relationships with Pacific island countries and enter into security agreements that are undermining Australian influence and security in the region.

The seriousness of the threat was underscored by Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s visit the Pacific soon after being sworn into office in an effort to reassure the region of Australia’s commitments to its neighbours. Her visit coincided with a 10-day, eight-country tour by China’s foreign minister and followed the signing of a security agreement between China and Solomon Islands.

While Pacific island countries declined to sign up to an extensive regional economic and security deal proposed by China, it’s unlikely that Beijing will see that as the end of the matter. We should therefore look for ways to bolster the security of the region, and—by extension—our own.

Our interests in maintaining a position as the security partner of choice in the South Pacific are clear. Pacific island countries sit strategically between us and our major ally the United States. A Chinese military presence in Pacific island countries gives it proximity to our major population centres that would reshape our peacetime military posture and restrict us to home duties in a regional conflict. While the Solomon Islands governments has ruled out a Chinese military presence under the agreement, it is sobering to note that Honiara is less than 2,000 kilometres from Cairns and its naval base.

The Pacific island countries themselves are also relatively undefended. Only Papua New Guinea, Tonga and Fiji maintain militaries of their own, and in each of those cases their military forces have a low level of capability that is directed mostly towards internal security, peacekeeping and a ceremonial expression of sovereignty.

For the rest, defence and security are handled by a mixture of diplomacy and police forces. Only the so-called Compact of Free Association States—Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and Marshall Islands—have formal security arrangements in place with the United States.

This model makes the US military the de facto armed forces for those states at the exclusion of all others. As part of this arrangement, the citizens of Palau, Micronesia and Marshall Islands can join the US armed forces. Even if deployed beyond the Pacific, citizens of these countries are in effect serving in the defence of their own nations, since they are part of the defence force that defends their country.

This is a style of arrangement Australia should consider with those Pacific island countries that don’t have defence forces of their own.

Under such an arrangement, Australia would provide a treaty-level security guarantee to defend a nation’s territory from external aggression. In return, the Australian Defence Force would become the de facto defence force of those countries, and their citizens would be able to join the ADF.

This would create not only exclusivity for security cooperation with Australia, but also employment opportunities for well-remunerated, skill-generating jobs in the ADF. These jobs would bring in remittance income and community interest in maintaining Australian security cooperation. The arrangement would also help build valuable people-to-people links between the ADF and Pacific island countries and improve cultural knowledge and understanding.

Such an arrangement would need to be enabled by more ADF exercises and interaction in those Pacific island countries. It would also require a modest increase in personnel deployed to the Pacific, which could be underpinned by a resident ADF officer serving as defence adviser to the relevant governments and the addition of ADF recruitment advisers to facilitate local recruitment.

If strategically it’s agreed that the security, stability of Pacific islands countries is important to Australia’s security, then we need to take steps to provide that security. Security guarantees and an ADF that is part of the local community in these countries would binds us to the so-called Pacific family in a way that is practically beneficial to both parties and negates the ambitions of our competitors.

This region—which is vital to our security and our interests—is being contested by an adversary with resources, time and an absence of democratic scruples. We need to take security partnerships out of that contest, and this could be the way to do it.

Managing relationships in the Pacific amid China’s push is a difficult task, and Australia still has some work to do in repairing its image, since all too often it is seen as ignoring the concerns of Pacific island countries. Fiji, for example, is worried more about the existential threat of climate change than the great-power competition playing out across the Pacific. Meanwhile, a paternalistic view that a chequebook can solve all problems hasn’t endeared many countries to Australia’s cause.

In that context, the direct and indirect benefits of deeper ADF links could well offer the sort of serious, long-term commitment that Pacific island countries have been seeking from Australia. Rather than simply offering dollars and positive sentiment, we would be working together to safeguard our futures and the security of the region.

NATO’s 2022 Madrid summit marked a shift to taking a truly global approach to strategic competition by including Indo-Pacific regional partners as participants for the first time. The presence of Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea—the so-called AP4—highlighted the increasingly global nature of security issues and perceived challenges to the rules-based international order. The summit declaration concluded:

We are confronted by cyber, space, and hybrid and other asymmetric threats, and by the malicious use of emerging and disruptive technologies. We face systemic competition from those, including the People’s Republic of China, who challenge our interests, security, and values and seek to undermine the rules-based international order.

In this context, NATO is preparing to convene its 2023 summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, next week. Among the issues to be considered will be developments in the war in Ukraine and the Russia–China ‘no limits’ partnership and their implications for NATO’s Indo-Pacific partners. The AP4 will be there again.

NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoana, in an address to the NATO and the Indo-Pacific Conference in Vilnius in April, clarified that while China is ‘not our adversary’, its ‘assertive behaviour and coercive policies challenge our values, our interests and our security’. He expressed concern about ‘the growing alignment of Russia and China’, noting that ‘China refuses to condemn Russia for its unjust and unprovoked war against Ukraine’. Instead, he said, China ‘seeks to maintain the appearance of carefully balanced neutrality, while also amplifying Russia’s false narratives and disinformation’.

NATO is thus seeking to strengthen relations with the AP4 and actively foster cooperation with like-minded countries around the globe.

A Chinese defence spokesperson later slammed the West for ‘judging China and China–Russia relations with a Cold War mentality’ and said that ‘under the strategic guidance of the Chinese and Russian heads of state, China and Russia have set up a paradigm of a new type of international relations and have forged their ties based on non-alliance, non-confrontation, and not targeting any third party’. Events in Ukraine and the militarisation of the South and East China Seas, however, don’t support these assertions.

The focus of the Vilnius summit will depend partly on whether Ukraine can drive Russian forces from enough of its territory to allow Kyiv to negotiate a stable peace with Moscow. Unifying NATO allies behind the goal of enabling a Ukrainian victory is a strategic priority. Last year, NATO’s entire force posture and planning were transformed after the Russian invasion and those measures were formally approved at Madrid. Vilnius could be similarly important.

Finland will also be welcomed as a full member, and Sweden’s accession, while delayed by Turkish concerns, should still be fast-tracked so it can fully participate in operational and defence planning, thus increasing Nordic–Baltic security.

The Atlantic Council identified a number of other security concerns for the summit. These include the extent to which Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative is strengthening China’s control over elements of critical European infrastructure, increasing Chinese influence operations aimed at undermining the political cohesion of NATO and Europe, China’s expanding security cooperation with Russia including support for its territorial ambitions in Ukraine, and President Xi Jinping’s commitment to growing China’s military capabilities and how that challenges the rules-based international order.

A Vilnius discussion session on China that includes the AP4 is planned to examine implications for both Europe and the Indo-Pacific if a US–China conflict were to erupt over Taiwan. With shared values of freedom, democracy and the rule of law under increasing pressure, Euro-Atlantic security is now viewed as interconnected with Indo-Pacific security. Indeed, the Lithuanian government this week approved its own Indo-Pacific strategy, paving the way for stronger bilateral connections with Australia.

For Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, this session will be of profound significance, bringing into sharp focus both the benefits and risks for Australia of ever-closer NATO links. While the war in Ukraine will dominate the summit, it’s also an opportunity to more critically examine the systemic challenge to the status quo posed by the rise of China and promote transatlantic–transpacific cooperation.

NATO’s leaders view their Indo-Pacific partners’ presence at the summit as more than symbolic. Potentially larger roles for the AP4—and other prospective regional allies—will be crucial to responding to China and Russia’s increasing alignment. With the military, economic and industrial implications of a war over Taiwan currently being calibrated with the aim of developing both deterrence and collective resilience, involving the AP4 in NATO’s planning has never been more important.

NATO allies at Vilnius will also be asked to address Chinese investment in their civilian infrastructure and its associated risks, and share their experiences of economic coercion, hostage diplomacy and intellectual property theft. They will also collaborate on supply-chain risks, political disinformation and strategies for countering foreign influence. Australia will benefit from being involved in these discussions.

The balancing act is most delicate—China is a crucial trading partner for so many—but Albanese’s attendance in Vilnius should show Australia’s support for democracy, peace and security, upholding the international rule of law, and solidarity with Ukraine, while still promoting Australia’s prosperity.

Hong Kong’s national security police celebrated the third anniversary of the draconian national security law by issuing arrest warrants for eight exiled activists, two of whom are in Australia. A HK$1 million bounty is on offer for each of them.

This isn’t a modern-day reward to capture violent criminals but a Dark Ages hunt for those who dare question and challenge Beijing’s authorities.

The Chinese government has always gone after those who express dissenting views, even if they are overseas. Although threats don’t always silence pro-democracy fighters, many choose to disappear from public view or disengage from politics in fear of retribution. Democratic countries should provide an environment for persecuted communities to express their peaceful political views that is safe from the terrorisation of a foreign government.

The arrest warrants are an act of intimidation of democracy activists whom the Chinese state is monitoring even after they have escaped its authoritarian rule. The efforts to silence them will follow the activists wherever they are.

The bounties are also a warning to democratic states that the Chinese government will not hesitate to reach into their sovereign legal territory—disproving the flimsy argument that China’s concern is with internal issues. The party-state will go to extreme lengths, including engaging international cooperation as a member of Interpol, to bring these fugitives back. It is a reminder that we are operating under very different systems of government and values. And while Australia’s objective is not to change China’s political system, nor should our ambition be limited to engagement through complicit silence.

Of the eight self-exiled activists named, two reside in Australia. Ted Hui is a former Hong Kong legislative councillor who was sentenced in absentia to three and a half years in jail for taking part in the 2019 protests. Kevin Yam is a lawyer and activist who has been increasingly vocal in lobbying the Australian government on Hong Kong immigration and human rights issues. He is also an Australian citizen.

Australia must ensure that democracy activists are protected and can continue to express their political views freely. Some have already suffered reprisals in Australia—for example, when Hui was reportedly assaulted at a restaurant in Sydney. Vicky Xu, a long-time ASPI analyst and fellow, has been harassed, targeted and intimidated in person in Australia and online for being critical of the Chinese government’s Xinjiang policies.

The Chinese government’s rampant efforts to silence overseas political dissent cannot be allowed to continue. For a country such as Australia not to vigorously oppose this intimidation amounts to aiding the erosion of human rights and democratic values.

Many people who have fled the Chinese state know that the government can still reach them regardless of where they are. The Hong Kong national security law applies to people outside of the city, including those ‘who are not permanent residents of Hong Kong’. Yam, who described himself last year as an ‘insignificant person’ who may not be impacted by the law, said: ‘You never know how the law will be enforced and where the red line is drawn.’

Beijing’s worldwide network of ‘police stations’ uncovered earlier this year is one part of the transnational repression campaign that is silencing dissidents or pressuring them to return to China. Surveillance cameras with exploitable programs operated by Chinese companies linked to the government are installed in countless public spaces, including in sensitive locations of departments and agencies in democratic countries. As well as posing national security risks to the country in question, they can also be used to track dissidents.

The intimidation sometimes becomes public and physical, as when a Chinese diplomat attacked a Hong Kong protester on British soil.

More broadly, persecuted communities consisting of everyday citizens must be in no doubt that they are supported and protected. Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s timely response specifically on Yam and Hui is a welcome first step in articulating the government’s longstanding concerns about the Hong Kong national security law. She said: ‘Australia has a view about freedom of expression. We have a view about people’s right to express their political views peacefully. And people in Australia who do so in accordance with our laws will be supported. We will support those in Australia who exercise these rights.’

But Australia’s official reaction needs to go beyond being ‘deeply disappointed’ in the issuing of warrants. The government should continue to express in the strongest terms its support for Yam and Hui and call the Chinese government’s behaviour out for what it is: an egregious attempt to impose its censorship abroad, in contravention of Australia’s democratic values, on Australian soil.

This is necessary to maintain a trusting relationship between these communities and the government. Any sense that Australia is prepared to blunt its response to avoid creating bumps in the road of the diplomatic relationship would taint our reputation and create distrust among persecuted communities. A strong Australian response to Chinese government intimidation boosts the faith of emigrants who have placed their freedom in the hands of the Australian government and who reasonably expect the steadfast defence of universal human rights, including the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

Ultimately, a response by the Australian government to the issuing of arrest warrants for pro-democracy activists is a public display of its commitment to Australian values. Despite the resets, re-engagements, stabilisation and thaws in the relationship with China, this incident is a stark reminder that Beijing is operating with values that are fundamentally different to those of democracies. Speaking out and condemning these arrest warrants is a stand against human rights abuses and the erosion of democracy in Hong Kong. It’s about upholding our own values.

In response to his sentencing in 2022, Hui said, ‘Since I am in a free country … it [the sentence] won’t harm my personal freedom or reputation, nor my international lobbying work.’ Australia must not destroy the trust that those who are willing to fight for democracy and who have been displaced had when they sought freedom and protection in Australia. That would be a destruction not just of individual trust but of our national integrity. Taking a stand and calling out unacceptable behaviour by the Chinese government is one step in building this trust, and a necessary step for Australian democracy.

The Australian government’s campaign to ‘stabilise’ the relationship with China appears to be bearing some fruit. A few channels of communication are being revived and access to the Chinese market is being restored for some Australian exports. Chinese diplomats have halted their ‘wolf warrior’ tactics and are signalling that more progress may be possible if both sides exercise ‘mutual respect’. But more smiles and the partial return to a normal trading relationship shouldn’t disguise the reality that Beijing hasn’t given ground on any substantive political or security issues and regional tensions remain high.

Indeed, in recent months Beijing has reinforced its aggressive operations in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea and announced a steep 7.2% rise in official military spending. Party secretary Xi Jinping has repeated his promise to the Chinese people that Taiwan ‘must’ and ‘definitely will’ be reunified with the ‘motherland’.

On the other side of the Pacific, President Joe Biden has said four times since his election that if Taiwan is attacked, American forces will be deployed immediately to defend the island. And the State Department has declared that the US commitment to the security of Taiwan is ‘rock solid’.

In consequence, the risk of major war in the Indo-Pacific is now very high; probably higher than at any time since World War II. Australians need to look beyond the ‘smile diplomacy’ and focus on preparing for the serious crisis that may lie ahead. We need to prepare now for the ‘dangerous storms’ and the ‘worst-case and extreme scenarios’ that Xi recently said were driving China’s planning and preparations.

Allied concerns about the risk of major war in the Indo-Pacific are not new. Senior American military commanders have repeatedly warned that the risk of a Chinese assault on Taiwan is high. According to CIA Director William Burns, Xi has ordered his military to be ready to assault Taiwan by 2027. In a recent Atlantic Council poll, 70% of the foreign policy experts consulted stated their belief that China would launch a military assault to seize Taiwan within 10 years. So, while war is not inevitable, it is a very serious risk. And it’s a risk that we can’t ignore.

Key questions we need to address include: What would a China–US war be like? How much notice would we have? How would Australia be affected? How long would such a war last? And what do we need to do now to prepare?

A Chinese attack on Taiwan could be launched with little or no notice. A surprise air, sea and cyber assault would likely aim to seize priority targets before US forces could intervene. But as soon as American forces are committed, China would probably launch intense missile, cyber and sabotage attacks on US, Japanese, Australian and South Korean military bases and other strategic targets across the Indo-Pacific.

Australia would then be fighting a major war alongside its allies that is unlikely to end quickly. The two sides have strong interests at stake and extensive capacities to sustain operations for several years. Neither is likely to collapse quickly. China is making extensive political, military, economic, infrastructure and other preparations to fight a long war and we must be similarly prepared.

The stakes would be very high. Taiwan is located in a strategically vital part of the Western Pacific. A successful Chinese invasion would punch a huge hole in the allies’ island chain defences, seriously undermining the defence of Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, the rest of maritime Southeast Asia and America’s own territories in the region.

An allied failure to effectively defend Taiwan would do huge damage to US and allied credibility and could precipitate an effective American withdrawal from much of the Western Pacific. That type of outcome would gravely damage Australia’s security.

What do we need to do to prevent such a catastrophe from occurring? How can we exert powerful deterrence and dissuasion power? And if we are forced to fight, what should we do to ensure that we and our allies win?

There are many things that need early attention but, in this article, I’ll focus on just four of the highest priorities.

First, on the military front, Australia needs to ensure that it possesses strong capabilities that can reach out a long way and give even the most powerful opponent good reasons to desist. Our military forces need to be dispersed and their supporting bases and infrastructure protected to ensure they can’t be destroyed in pre-emptive strikes.

The recent defence strategic review contains encouraging words on these issues, but it is distressing to see that the May budget adds little to already planned defence expenditure. Indeed, the government plans to cut spending on defence equipment and facilities (capital) during the coming three years. Ministers are clearly not seized by a sense of urgency.

But the military challenges are only part of the story. Another need is to find better ways of protecting our media, key agencies, businesses and the broader Australian community from Chinese influence, coercion, cyber and broader political warfare operations. We are currently very vulnerable to the types of disruption and dis-integration operations Chinese agencies are refining. Some technical fixes can help, but a whole-of-nation effort is required that includes major public education programs.

A third priority is to reconfigure the country’s international supply chains of critical goods and services. There’s an urgent need to shift production of everything from fuels to pharmaceuticals, processed metals and key manufactured goods to Australia, our allies and other trusted partners. We cannot rely on supplies coming from potentially hostile states in an emergency.

Fourth, we and our allies must face up to the fact that during the past two decades China’s manufacturing output has surged past that of the United States. America no longer possesses the overwhelming industrial capacities that contributed so much to the allied victories in both world wars. For the allies to retain their strong deterrence and defensive power, their longstanding dominance of global manufacturing must be restored and Australia has a key role to play.

Giving the Australian economy the flexibility to rapidly adapt to the demands of a major conflict will require a marked reordering of our priorities. We will need to rebuild many of the manufacturing capacities we have exported during the past 50 years, primarily to China. In 1960 manufacturing generated 28% of Australia’s GDP, but it now contributes only 6%. This has made us very vulnerable to external pressures. We need to urgently rebuild domestic and trusted international production of priority supplies.

That can be done, but it will require serious industrial reforms, a dramatic rise in productivity in all parts of the economy and new levels of business cooperation between the allies and other trusted partners.

Higher levels of economic competitiveness and societal resilience and endurance cannot be achieved by the government heavily subsidizing a few boutique manufacturing operations. The heavy lifting will need to be done by industry and Australia’s broader community. For that to happen, incentive structures will need to change. Businesses must be able to see viable economic opportunities that justify their investments. Government overheads at all three levels of government need to be reduced and unnecessary regulatory burdens abolished.

The country needs to be gripped by the pressing security challenges and a new mindset championed that embraces substantial productivity reform. We must pursue every avenue to make Australia an attractive destination for manufacturing and advanced technology investment once again.

Proper exploitation of our rich resource base with world-leading processing of highly competitive minerals should play a key role. We need once more to offer the world’s cheapest and most reliable energy supplies, highly efficient infrastructure and a very skilled and flexible workforce.

If we don’t embrace reform, we will become a backwater mining and tourist economy with low prosperity and little international influence. Worse still, Australia will be highly dependent on others for security and extremely vulnerable in future crises and wars.

The US, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea appreciate the risk of major war and are already taking big steps to bring strategic manufacturing home or transfer it to fully trusted security partners. If Australians want to maintain their security and independence, we need to move quickly to do the same.