Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The five-year icy age between Australia and China has wound down. The leaders have met, and enough fitful warmth has returned to melt a few icicles.

The icy age can be mapped and dated as running from 2017 to 2022.

The emerging era, though, still has plenty of iciness. A renewed chill hit with the news of China’s suspended death sentence on the Australian citizen, Dr Yang Jun.

Penny Wong’s press conference on China’s decision was a notable display of the foreign minister in steely-anger mode. Take the temperature from the first six paragraphs of her media statement: Australia is ‘appalled’ at the ‘harrowing news’ which causes ‘acute distress’. The ‘many years of uncertainty’ since Yang’s detention in January 2019 were ‘extraordinarily difficult’ and the Australian government ‘will be communicating our response in the strongest terms’.

What’s changed compared to the five-year icy age is that Australia will be able to speak to Beijing at the highest level; the calls should be taken even if the message is rejected. The punishing previous age of no-talk-no-contact is ebbing, but these new times of ‘stabilisation’ can still see-saw.

The stabilisation imperative meant Wong swatted away questions about Australia withdrawing its ambassador from Beijing in protest (Canberra has no interest in returning to that no-talk-no-contact iciness). And the stabilisation ambition saw Wong swiftly step over a question about whether Australia still wants to host a visit this year by China’s president or premier.

The fact that such a visit is even on the cards is part of the stabilisation success—the see-saw has its ups.

To see what Australia and China face, map the features of the icy era, a fraught history that will shape and limit future expectations.

The chill that ran from 2017 to 2022 is the fifth China-Australia icy age in 70 years. Here are the four previous icy ages:

Since diplomatic recognition in 1972, the five-year icy age is the longest and broadest, touching every area of the relationship.

The early frostiness in 2017 was marked by Australian pushback. Describing China as a ‘frenemy’, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull offered a ‘dark view’ of a ‘coercive China’ seeking regional domination. A Labor senator fell for doing China’s bidding because of political donations from Chinese business.

Turnbull introduced legislation on foreign interference in December 2017, stating the Chinese Communist Party worked covertly to interfere with the Australian parliament, media and universities. The law banned foreign political donations and broadened the definition of espionage. Turnbull responded to Beijing’s anger by using a defiant line from Mao Zedong’s 1949 victory statement: ‘The Australian people stand up.’

Chinese pressure sunk Quad 1.0 in the first decade of the century. In 2017, Chinese pressure got the band back together, as the United States, Japan, India and Australia formed Quad 2.0.

By 2018, Canberra was sounding loud alarms—in public as well as privately–at China’s challenge to Australian interests in the South Pacific. An old Canberra line is that some regional governments can’t be bought but they can be rented. Today’s version is that China wants to do more than rent; it wants a lease.

Beijing got heartburn at Canberra’s refusal to join the Belt and Road Initiative. In the week the Liberal Party toppled Turnbull as PM in August 2018, Australia became the first nation to ban ‘high risk’ vendors (read: China’s Huawei and ZTE) from building its 5G network. Barring China from the 5G build, Turnbull later wrote, was ‘a hedge against a future threat: not the identification of a smoking gun, but a loaded one.’

Australia’s call for an international inquiry on the origins and development of the Covid-19 pandemic in April 2020 took the chill to its iciest place. For China’s Xi Jinping, facing the greatest crisis of his leadership, this was getting personal.

By November 2020, China’s embassy in Canberra was talking of Australia ‘poisoning bilateral relations’ and treating China like an ‘enemy’. The embassy gave journalists a list of 14 grievances/disputes where Australia had offended.

The rap sheet was classic China: it’s all Australia’s fault. Beyond the bombast, the 14 points offered a useful list of many positions Australia wouldn’t recant on: Huawei and 5G tech; foreign interference legislation; Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

In 2020, Beijing hit the economic coercion button, slashing purchases of a dozen Australia products from beef and barley all the way down the produce alphabet to wine. The retribution cut the value of Australian trade with China for almost all industries by 40%, costing $20 billion (only China’s huge appetite for iron ore sustained the dollar value of total exports).

At Australia’s federal election in May 2022, the Labor-Liberal foreign policy consensus was crammed into a single phrase: ‘China has changed’. Both parties called for Beijing to start talking again and to cease trade coercion.

With the election of the Labor government, the reset chance arrived. On the day Anthony Albanese was sworn in as prime minister, he boarded a plane to fly to Japan for a Quad summit. Not just China has changed. So have the times. The melt is a slow work in progress.

Date the symbolic declaration of the end of the 5th icy age as November 2022, when Albanese had a bilateral meeting with Xi during the G20 summit in Bali. As with the icy periods during the Hawke, Howard and Rudd governments, the chill begins to ebb when the leaders do grip-and-grin for the cameras and resume the conversation.

Most of the trade sanctions have been lifted. Australia did not bow and China caused minimal economic damage.

Australian exporters shifted to other markets. And China could not do without the iron ore, so the trade surplus with China kept surging, despite the bans. A study by the Productivity Commission found that China failed to ‘impose significant economy-wide costs on Australia’ although individual businesses were hit. The Commission said ‘alternative markets were readily found’ and exports ‘proved to be mostly resilient against these [Chinese] trade measures’.

The seal on the stabilisation effort was Albanese’s visit to Beijing in November 2023, when Xi said he was ‘heartened’ that the relationship had ‘embarked on the right path of improvement’.

The current weather forecast for the relationship see-saw reads: ‘warmer days with the chance of sudden storms’. The diplomatic version is ‘relatively stable and balanced’.

Canberra doesn’t expect to go back to the balmy days before the five-year icy age. The aim is for strategic equilibrium, in the bilateral with China and for the Indo-Pacific.

Some wise owls outside the Labor government talk of the need for ‘détente’. The détente idea was prominent in the statement by 50 prominent Australians (including former Labor foreign ministers Gareth Evans and Bob Carr) calling for Australian middle-power diplomacy to help achieve ‘a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region in which the United States and China respect and recognise each other as equals’.

Détente between China and the US was what the wise owls want. What the Albanese government seeks is also a form of China-Australia détente. Strip away the Cold War overtones and the détente ambition looks a lot like that ‘relatively stable and balanced’ aim—more sunny days, fewer icy winds.

Hostage diplomacy is an apt name for the exquisite predicament in which Australia finds itself. An Australian citizen, Yang Hengjun, is held arbitrarily and then, in a shocking decision, sentenced to death. But with the diabolical twist that the sentence is suspended for two years dependent on good behaviour.

Whose good behaviour? Not Yang’s but ours—Australia’s. With Yang as a hostage, Australia is being blackmailed into submission and silence.

Beijing is masterful at planting self-doubt in the minds of rivals. If we speak out against Chinese bullying of neighbours in the South China Sea, will Yang be executed? If we name China as a perpetrator of cyberattacks, will Yang be executed?

If you are worried about what another party might do, they are in control. So, we need to make Beijing worry more about what we might do.

As a smaller nation that abides by rules and norms, the way to do that lies in collective action. Rather than try to walk this treacherous tightrope alone, Australia needs to work with liberal democracies to establish a coalition of nations that can respond to hostage diplomacy and impose a cost—from economic to reputational—on nations that abuse the rule of law this way.

And we are not starting from scratch. In 2021, the democratic world signed the Canada-led Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations. Canada was driven by the experience of having two of its citizens, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, detained arbitrarily because Ottawa agreed to consider an extradition request by the United States for Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer to the telco giant, Huawei, whom US authorities accused of fraud.

Canada’s stoutness demonstrated that when a country stands up to bullying, it is standing up not just for itself but for everyone who believes in rules and norms.

The 2021 declaration was a good start, but it needs enforcement mechanisms to stop it being toothless. Australia should start with the Five Eyes group—our partnership with Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the United States—and the G7 nations, which adds France, Germany, Italy and Japan. It should also encourage participation from other countries that have citizens arbitrarily detained, such as Sweden with Hong Kong publisher Gui Minhai held since 2015. Countries that have experienced Moscow’s and Beijing’s bullying, like Lithuania and other European Union members, would also be powerful partners.

It must be clear to Beijing, and all totalitarian regimes such as Iran, that they will be held to account when they try to blackmail another country through hostage diplomacy. The only way to deter a malign actor is to convince it that its actions won’t work, and moreover there will be costs. A good recent example of such collective action was the use by Australia, Britain and the US of Magnitsky sanctions laws to target the Russian hacker behind the Medibank breach. Coordinated sanctions help tighten the net around a criminal’s assets.

No one should doubt this is a tough balancing act for Foreign Minister Penny Wong. She is rightly prioritising Yang’s welfare, and therefore the immediate step is to continue the most strenuous representations for Yang’s health and wellbeing.

That means medical care, books, contact with his family and a pathway to him being freed and returned to Australia. He should never have been jailed, and he certainly should not have been sentenced to death. His detention in reportedly harsh and even cruel conditions is a continuing abuse of a man in his late 50s with significant medical ailments who is likely not getting adequate care.

Wong responded on Monday with a clear denunciation of Yang’s sentence. She also trod carefully, saying this was a decision by the Chinese legal system. In truth, there’s no separation between the party-state and the courts in China, but Wong’s language may give the Chinese government space to step in and commute the death sentence.

Yet, this must not mean any kind of backward step by Australia on issues key to our values and long-term interests. If we let ourselves be tugged onto a slippery slope of submitting to Beijing’s coercive will, the coercion will continue. And unlike, say Iran, which has taken prisoners as bargaining chips in straight out government-to-government transactions, Beijing tends not to offer any kind of clear exchange but rather builds pressure for long-term submission to its core strategic objectives.

Hence, for Wong, short and long-term goals arise from the Yang case.

Long-term, it’s about having as many countries on our side as possible so that Beijing recognises that to execute an innocent citizen of another country is no longer just a bilateral issue with a smaller power, but a global issue. The risk-benefit calculation changes dramatically.

It’s time for Beijing to stop assuming it can worry Australia, and start worrying about what Australia might do. In this case, we can fight for Yang and our democratic sovereignty.

On 4 January, three officials from Maldives’ Ministry of Youth Empowerment, Information and Arts criticised India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to India’s smallest union territory, Lakshadweep.

They labelled Modi a ‘puppet of Israel’, a ‘terrorist’ and a ‘clown’, prompting a public backlash in India and calls to boycott Maldives as a tourist destination. Hashtag #BoycottMaldives quickly trended online and the social media frenzy soon escalated into a diplomatic row between the two nations.

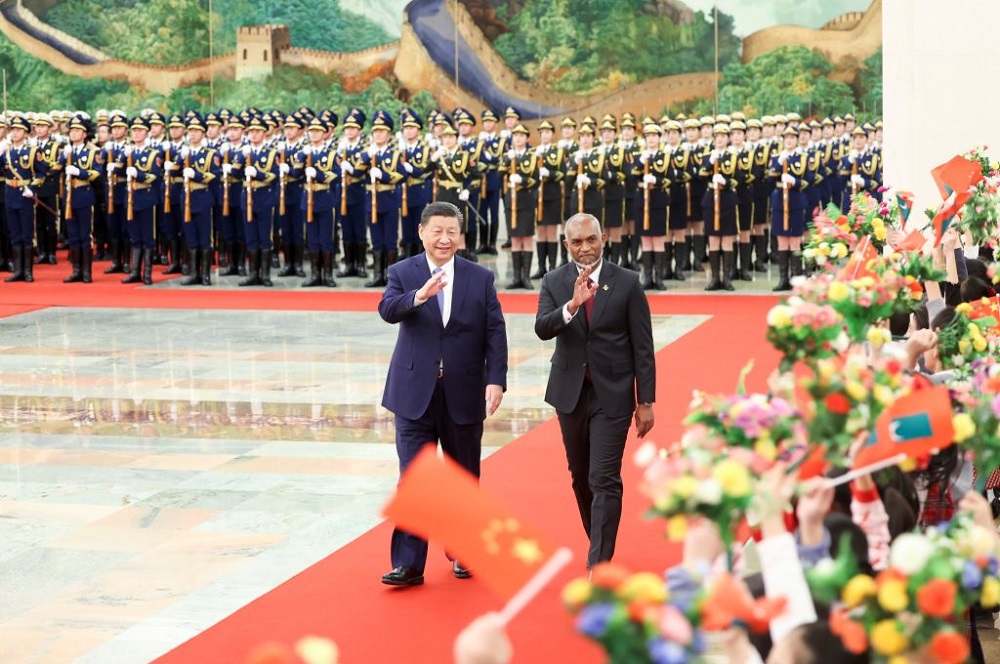

Maldivian president, Mohamed Muizzu, known for his pro-China sentiments, further aggravated tensions by snubbing India and making his first state visit to China after an official trip to Turkey. While the Maldives’ government suspended the loose-lipped officials, Muizzu’s shift towards more China-friendly foreign policies raises concerns about the balance of international relations in the region.

If the Maldives government drifts closer to China, and if its relationship with India remains strained, there may well be strategic and economic consequences for both India and the Maldives in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

India and Maldives have a complex historical relationship, primarily influenced by Maldives political leadership. Despite historical ebbs and flows, India has often been the first to respond to crises in Maldives including intervening in the 1988 coup against President Abdul Gayoom, and recently providing $250 million in financial assistance.

In 2009, Maldivian President Mohammad Nashid strengthened ties with India, signing a comprehensive security agreement allowing an Indian military presence in Maldives. Indian forces conducted search and rescue missions and joint patrols. They also monitored Chinese illegal fishing in the Indian Ocean in response to an increase in incidents from 372 in 2020 to 392 in 2021.

India-Maldives relations were strained between 2013-2018 by President Abdulla Yameen’s ‘India Out’ campaign aligning Maldives with China to lessen India’s influence over his country’s security. Chinese investments through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and general trade flourished with Chinese tourist numbers rising from 60,000 in 2009 to 360,000 in 2015. Yameen’s China-friendly policies led to high indebtedness and then the leasing of 17 islands to China.

Maldives foreign policy shifted again in 2018 with President Ibu Solih’s ‘India First’ campaign, which restored India’s strategic position as the primary security provider to the IOR.

President Mohamed Muizzu’s election in September 2023 brought back Yameen’s ‘India Out’ campaign which was likely supported by political disinformation and online amplification. A report by the European Election Observation Mission (EU EOM) revealed that Muizzu’s ruling coalition of the Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) and People’s National Congress (PNC), ran disinformation campaigns across social media platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, to influence public opinion and manipulate election results. The report states that their campaign included anti-Indian sentiments, based on fears of Indian influences and anxiety regarding a presence of Indian military personnel inside the country.

Since coming to office, President Muizzu has dramatically reset Maldives’ international relations. He broke tradition by visiting China before India. He requested the withdrawal of Indian troops by 15 March 2024 and signed a USD$37 million deal with Turkey for reconnaissance drones to replace the gap to be left by the withdrawal of Indian security. To decrease reliance on India, Maldives plans to import staple foods from Turkey and explore alternative sources of pharmaceuticals. During Muizzu ‘s recent five-day visit to China in January 2024, he and Xi Jinping signed 20 agreements spanning disaster risk reduction, fisheries, increased digital economy investment, joint acceleration of the BRI, and tourism among others.

So, why might the Maldives’ rapprochement with China be of concern to both Maldives and India?

If Muizzu merely switched Maldives’ economic dependency from India to China, he would drag his country further into the debt trap. Maldives’ share of Indian tourism increased from 6% in 2018 to over 14% in 2022. By turning away from India, Muizzu risks losing a major chunk of tourism revenue (accounting for 28% of Maldivian GDP in 2023) generated by Indian travellers to the islands. Recognising that 90% of the Maldivian economy is dependent on tourism-related activities, Muizzu has now urged China to ‘intensify efforts’ to send more of its tourists to Maldives. Increasing Maldives economic reliance on China will only further Beijing’s goals in the region.

And Turkish drones alone cannot match the vital role played by Indian troops in Maldives’ security. India, a long-standing ally since the 1988 coup, not only assisted in various operations but also provided crucial aid during the 2004 tsunami and 2014 water crisis in Male. Despite President Yameen’s attempts to engage with China and Pakistan, India continued to fulfill 70% of Maldives’ defence training needs.

Allocating $37 million for Turkish drones from a strained budget raises concerns about the project’s viability in a growing debt crisis. The money will buy Maldives at most five or six Bayraktar TB2 drones. While Maldives is aiming for a more sovereign foreign policy and does not intend replacing Indian troops with forces from other nations, it may still struggle to monitor the exclusive economic zone around its archipelagos with a limited number of drones and a small military.

From India’s perspective, China’s engagement with the Maldives adds to the pressure New Delhi faces in protecting its interests in the Indian Ocean. In this era of geopolitical contestation, having increased Chinese influence in its backyard is not welcome given that Sri Lanka is already enmeshed in debt-trap diplomacy and Pakistan’s dependence on China has increased through the BRI initiative.

Islamic radicalism in Maldives poses a security threat to India and other neighbouring countries. Maldives provided the highest number of foreign fighters per capita to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) terror group. That reached its peak during Yameen’s presidency from 2013-18. The political leadership has been accused by some analysts of turning a blind eye to the extremist recruitment to secure votes. Extremist gangs organising out of Maldives lured young men into their gangs in the name of religion, promising them a better future, a sense of purpose, and material wealth. As an example, the 2022 attack on Indians during an International Yoga Day event organised by the Indian High Commission in Maldives highlighted the threat which persists despite efforts by international partners such as Japan which granted 500 million yen (US$4.5 million) to Maldives to boost its counter-terrorism capabilities. Despite some attempts to reintegrate families of extremists, the rise of anti-India sentiments in 2024, coupled with Muizzu ‘s emphasis on Islamic values, raises India’s concerns about heightened terrorism.

A push to shift the focus of tourism from Maldives to India’s Lakshadweep islands may have unintended environmental consequences. Indian investors have already made plans to set up 50 luxury tents and more permanent resorts, and the hashtag #ChaloLakshadweep (‘Let’s go to Lakshadweep’) is trending on social media.

The Lakshadweep islands are undoubtedly beautiful, but they are smaller, unexplored, and underdeveloped in terms of infrastructure, internet connectivity and manpower compared to Maldives. While one could argue that a boost in tourism might drive economic development, environmentalists have raised concerns that large-scale human interference would strain existing capacities, generate waste and exacerbate climate change, endangering the island’s fragile marine ecosystem and threatening livelihoods. It urges prioritisation of environmental risk assessments and sustainable infrastructural plans to head off a development frenzy driven by the social media feud over the Maldivian officials’ comments about India’s prime minister.

Considering that Maldives is a geopolitical hotspot, and India seeks to maintain strategic influence in the IOR, it is important that both nations recalibrate their actions and responses to better tackle the existing situation and reinforce mutually beneficial ties.

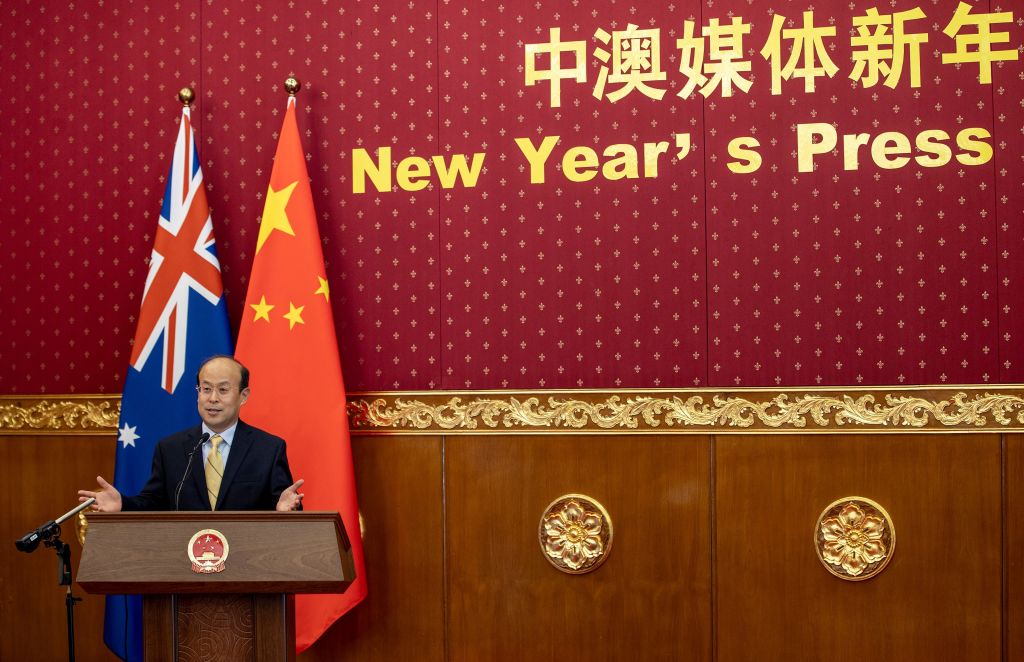

Last week’s Chinese embassy press conference was a further effort to corral Australia into compliance and compromise with Beijing’s views.

Remarks by Chinese ambassador Xiao Qian and other embassy officials confirm what many national security observers have been worried about for months.

If we pull our punches, if we subordinate our values and long-term interests to a short-term effort to orchestrate a trouble-free diplomatic relationship, we won’t actually buy stability. Rather we’ll find ourselves on a slope where nothing we do is good enough, and we will be eternally tempted to find unilateral compromises.

The embassy press conference demonstrated Beijing is looking for Australia to keep sliding ever closer to positions that will satisfy the Chinese Communist Party.

Questions about the sonar burst that our government says injured Australian naval personnel prompted an official to warn against making trouble on China’s doorstep.

Questions about the Taiwanese election elicited further demands that Australia stay silent when Taiwan freely elects a new leader.

These would be breaches of Australia’s core values. We have every right to operate in international waters as HMAS Toowoomba was doing in support of a United Nations mission late last year. And Australia should never shrink from championing the expression of democracy through free and fair elections, as we have through statements on Taiwan’s election that were actually fairly mild.

The day we fail to celebrate people’s participation in their own government—something mainland Chinese people don’t enjoy—is the day we might as well pack our bags and go home, geopolitically speaking. Xiao stated bluntly that Beijing could show no flexibility or compromise on Taiwan, meaning any shift to smooth the waters would have to come from Australia.

Stabilisation is the stated goal of the Australian government, but Beijing has a different definition of stability. Australia wants to co-operate where we can and disagree where we must, but Beijing doesn’t accept when we disagree. This was clear from Xiao’s opening remarks, which painted an ambitious picture of an ever deepening relationship that ignored differences and sought increased co-operation, including joint defence exercises.

How could we seriously have joint exercises with a military that is bullying a democratic nation in the Philippines through steady and calculated harassment of its vessels in the South China Sea? We couldn’t speak out with a straight face the next time the Chinese navy used water cannon on a Philippines ship. But that’s the idea.

Beijing is trying to achieve its strategic objectives through aggression, coercion and threats. This is its own doing, not Australia’s. Xiao’s naked threat to Australia ahead of the Taiwan poll, warning that support for Taiwanese independence—which is not Australia’s position—would push the Australian people ‘over the edge of an abyss’ should be intolerable.

For the sake of staking out consistent positions on core issues, Canberra should make clear that such remarks are unacceptable. While unlikely to change Beijing’s malign objectives, we would send a signal that stability, to us, doesn’t mean submission, but prioritising our own security, transparently and consistently.

Sonar attacks, threatening Australians with the abyss, unfair trade sanctions—they all demand condemnation because they are breaches of rules and norms that are essential to our region’s future. Inconsistent responses only contribute to the degradation of the rules that have helped keep us secure since 1945.

Xiao also continued the recent Chinese government effort to drive divisions between Australia and Japan, hinting preposterously that the Japanese Armed Forces might have been responsible for the sonar attack.

This points to another Beijing ambition—ham fisted though its execution might seem. It would prefer that regional partnerships are weakened so that it can manage others bilaterally, giving it a sizeable advantage.

But Australia needs friends, partners with whom we co-ordinate and collaborate. We can’t have regional stability unless we work together to balance and deter China, impose costs for its transgressions and gradually persuade it that bullying and coercion will be ineffectual and detrimental to its own interests. Stabilisation can’t become code for tolerating Beijing’s destabilising activity. The UK made this mistake in the 1930s, with disarmament and appeasement policies that tolerated German rearmament and illegal land grabs.

As we start 2024 with increasingly confident authoritarian regimes, wars in Europe and the Middle East and increased tension in the Indo-Pacific, democracies like Australia are faced with two roads diverging. The pathway ahead is not a confected improvement to the bilateral relationship with Beijing that rests on our biting our tongue and entering into arrangements that only leave us more vulnerable, such as returning to an excessive and risky trade dependence.

We are no longer in a period of stability to be maintained but an era of instability that means a business-as-usual approach will be insufficient. Our approach needs extra effort ranging from greater defence investment to diplomacy that manages tensions rather than ignoring them—because whatever the rhetorical niceties, our long-term values shouldn’t be sacrificed for short-term interests. Both roads cannot be travelled.

China’s recent decision to expand the pilot planting of genetically modified soybeans has the potential to reshape the global soybean trade.

Soybeans, crucial in animal feed, human food and industrial products, are immensely important in China. Although the country is a major soybean producer soybean production at 20 million tonnes, China is remains the world’s largest importer, accounting for more than 60% of global demand.

The imported soybeans are genetically modified and mainly used to produce cooking oil and animal feed, while locally produced non-GM soybeans are used primarily for direct human consumption such as in tofu and soy sauce.

With more than 88% of soybean consumption as food relying on imports, China is vulnerable to global market fluctuations. In 2021 alone, China imported more than 100 million tonnes of soybeans, mainly from Brazil, the US and Argentina. This was a 13.3% year-on-year increase from 2020. In 2022, China imported an estimated 91 million tonnes.

Systemic competition between the US and China and the ongoing Ukraine–Russia conflict are affecting China’s soybean policy. Beijing is looking to boost domestic soybean production to address concerns about reliance on foreign soybeans exposed during the Trump-era trade war.

Mutual mistrust in US–China relations and the possibility of Donald Trump returning for a second term make questions about the relationship’s trajectory urgent. While China recently bought American soybeans, ostensibly as a gesture of goodwill, it remains to be seen whether the US will maintain its role as a major soybean supplier to China.

This provides Brazil with an opportunity to strengthen its trade with Beijing. A leading soybean exporter and fellow BRICS economic group member, Brazil already sends more than 70% of its soybean exports to China. With new bilateral agreements in place that address agricultural cooperation, Beijing may look to buy more Brazilian soybeans in place of American imports.

The pressure of testy US–China relations has made it imperative for China’s policymakers to increase local soybean production, including through GM seeds. Soybeans play a crucial role in China’s economy and Beijing consistently emphasises the need for increased local production in its policy measures, targets and five-year plans. Recent efforts, like draft rules on registration requirements for herbicides used on GM crops and the 14th Five-Year Plan on Bioeconomy (2021-2025), have highlighted the government’s commitment to exploring agricultural biotechnology for human consumption at scale.

Despite its vast population, China grapples with limited water and arable land, compounded by soil quality issues and the escalating effects of climate change. Although plans to commercialise GM crops as food remain implicit, they align with China’s broader food security strategy.

China’s push into GM soybeans will face obstacles. Public perception is a significant challenge. Despite being an early adopter of GM crops for human consumption, commercialisation in China has stalled partly due to public opposition.

Strong scepticism among consumers has combined with suspicion of Western threats to the country’s food security to create a negative perception of GM foods in China’s population. Recent surveys indicate that 55% of Chinese consumers are opposed to eating GM foods, with nearly 60% lacking trust in scientists studying the issue. Another survey, from 2018, found that only 12% of Chinese consumers viewed GM food positively.

Adding to this public relations battle is a struggle with the effects of social media. Concerns are consistently spread online about GM foods, including that eating them could cause serious illness. This is hindering Beijing’s commercialisation of GM soybeans and other crops, but with 40% of Chinese respondents willing to accept GM-labelled foods, there is still hope that this is enough demand to get things off the ground.

Still, addressing public opinion will be critical to China achieving better food security through GM agriculture. Responding to public concerns, China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs dismissed these claims and asserted the safety of approved genetically modified products.

Having acknowledged the need for better public understanding of biotechnology, Beijing is using state media to try and dispel some scepticism. Articles published in 2022 by Xinhua and China Daily, for instance, showcased the successful outcomes of a GM food environmental and food safety assessment.

The Chinese central government is showing that it’s aware of China’s complex food security challenge. To achieve a higher usage of GM technology in agriculture it has commenced GM pilot programs to gradually introduce domestically-produced GM soybeans and other crops into the market for human consumption.

It has also sought to diversify soybean import sources to ensure a stable supply, and prioritised agricultural trade relationships with ‘China-friendly’ countries like Brazil and others with significant Belt and Road projects.

Importantly for Australia, this could have flow-on effects that reshape global and regional trade flows. A reduced dependence in China on imported non-GM soybeans could result in greater supply, lowering prices and affecting the bottom line for other exporting countries. It may also provide opportunities for other countries to import China’s surplus soybeans, influencing global market dynamics. And amid escalating global food insecurity concerns, it could also pave the way for greater Sino-Brazilian bilateral trade in other areas and trigger closer food cooperation among BRICS members.

While not itself a major soybean exporter, Australia could benefit from indirect changes to China’s soybean and edible oil consumption. Additionally, Australia could harness China’s interest in yield-increasing technologies to export agricultural expertise and equipment.

In the longer term, the likely commercialisation of GM crops that extend to major Australian exports like barley are the most concerning and cast uncertainty over the future of these commodities in the Chinese market.

With more resilient local food supplies, China could reshape agricultural exports more generally, affecting Australia across the sector. Aside from Australia potentially having to find alternative markets for its products, a well-fed China could also export more of its own agricultural products in competition with Australian exporters. Whatever the exact impacts of China’s GM food push, a more food-secure China is always worth watching by Australian policymakers.

As I’ve previously argued on this forum, conceptions of the virtues of a historically China-centric regional order are deeply ingrained in Chinese society, including among a new generation taught from infancy to resist external threats to China’s great rejuvenation.

As we enter something of a new and perhaps less consistently hostile phase in our bilateral relationship with China, it’s worth taking stock of how we think ideological considerations practically impact China’s international relationships, including China’s views and actions with respect to Australia.

We should have lots of questions about this, even if we know the answers are going to be hard to find.

While it’s healthy (and a practical necessity in busy times) for policy practitioners in Canberra to avoid hovering too long over the black box of Chinese decision-making visa-vis Australia, those of in the peanut gallery have more leeway to do so and should have a guess at its contents from time to time.

The extent to which China’s statecraft is shaped by Beijing’s belief in the superiority of China’s political model is one question we could probably tackle more earnestly.

Does this belief meaningfully shape China’s day-to-day assessments of its external environment? Or is it for the most part an artificial construct designed to be occasionally exaggerated by China’s leaders for domestic-political purposes, meaning we can safely discount it as a serious vector in our relations with China?

It has always seemed to me that China’s belief that its political model will eventually prevail over all others, certainly the liberal democratic alternative, is a real and enduring source of Beijing’s self-confidence in China as an international actor.

China’s leaders believe it and need to because it helps them deal with everything going on around them.

For this group of Chinese leaders, all serious questions about power and cooperation should, and often need to be framed in terms of an existential struggle. It is a struggle not just against external powers seeking to prevent China from assuming its historically dominant position in the region, but also a struggle against those standing in the way of China exporting its political model to the region and beyond.

Because we don’t have a long history of conflict with China, as many other regional actors do, it is the latter consideration that Beijing would care about most with respect to Australia. Being able to easily influence a middle-sized liberal democratic country with an open society and ideological alignment with its major rival proves to China that’s its model is indeed the best.

And not being able to impose such influence undermines that confidence.

If this is something akin to China’s current mindset with respect to Australia, which I suspect it is, it follows that China’s leaders’ views of us are more heavily influenced by ideological factors than we had previously thought.

Some of our analytical frameworks and assumptions with respect to China that overstate tactical and material motivations may need to be requestioned.

One of those is the view that China’s leaders don’t care about what we say or do because we are a benign middle power with no real means to shape the current regional security environment. If only we had more power to project we could get more attention from Beijing, so the logic goes.

Until then we are hemmed into the economic and trade lane.

This view is misguided because it presupposes that hard power is the only way to threaten China’s interests and demonstrate our resolve.

This is clearly not the case.

If you think about it, and particularly in the terms set out above, what could be more threatening to China at this stage of its development than a middle power with limited power projection capabilities withstanding a prolonged campaign of economic coercion from the dominant power in the region, and emerging pretty much unscathed?

This is exactly what we did.

No acquisition of military hardware could have sent a clearer message to China than that about Australian resolve, and that is something to hang our hat on.

More recently, sharply pointed warnings from China’s Ambassador to Australia about the level of acceptable Australian engagement with Taiwan’s newly elected president provide further evidence that ideological considerations influence Beijing’s perceptions of us in serious ways.

Australia is fundamentally adaptable and resilient. We’ve already demonstrated that we can more appropriately balance economic and national security considerations vis-a-vis China, and we are more than capable of adding an ideological layer to our assessments of China’s international behaviour and whatever is going on inside China itself.

We need to though, because being able to assess China from multiple angles at once will give us an important additional tool to help us deal with whatever challenges emerge in an increasingly contested Asia.

And, let’s face it, we’re probably going to need the whole kit.

China’s demand for Australia’s iron ore is the gift which keeps on giving. It took off in the second half of 2005 and has helped to deliver the Australian economy an amazing $1.2 trillion since then.

After 18 years, the long boom in iron ore prices is still yielding about $32 billion in export revenue every three months according to the Department of Industry.

While governments in the United States and Europe wrestle with how to stop Chinese competition undermining their manufacturing industries, Australia has been enjoying a seemingly endless bonanza. It is a difference that cannot fail to inform our foreign policy towards China.

The iron ore market price last week reached its highest point since March, surpassing US$130 a tonne. Some analysts expect it to rise further as the Chinese government endeavours to lift growth with stimulus measures.

The Australian miners’ cash costs are about $20 a tonne so the profits, federal company tax revenue and state royalties have been enormous. The super profits are effectively a transfer of wealth from China to Australia.

Department of Industry data on the volume and value of Australia’s iron ore exports show the average received price rose above $50 a tonne in the September quarter of 2005, which was more than double the long-term average. It has never dropped below $50 over a quarter since.

Over almost two decades, it has averaged $102 a tonne, rising to an average of $155 over the last three years. The actual spot prices (quoted in US dollars) in traded markets are a lot more volatile, but quarterly receipts provide a comparison with costs and guide to tax payments.

The Australian Tax Office’s latest corporate tax transparency report, released earlier this month, shows the resources sector delivered half all company tax revenue in 2020-21. In 2017-18 the resource sector was paying $16 billion in company tax revenue. Four years later, the resource sector’s company tax payments had risen three-fold to $42 billion.

West Australia’s iron ore royalties have captured an average of $10 billion a year over the last three years and have pumped $66 billion into the state over the last decade, according to state budget documents.

Since 2005, Australia’s total iron ore export income has risen from $8 billion a year to $124 billion, while the volume shipped has risen from 230 million tonnes to just under 900 million tonnes.

China and Australia are bound together on iron ore in a mutual dependency. China takes 85% of Australia’s iron ore exports, and Australia accounts for 61% of China’s iron ore imports. Australia’s iron ore exports to China are three times the size of those from next-ranked Brazil. The Chinese price for Australian iron ore sets the world market.

Iron ore was notably exempted from the Chinese government’s three-year campaign of economic coercion against Australia because the Chinese steel industry cannot do without it.

China does not like being so bound to Australia and does not like handing super profits to the big iron ore companies: BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue and Hancock Mining. However, since 2010, when BHP and Rio Tinto effectively forced the Chinese steel mills to abandon the annual contract price fixing negotiations over which the Chinese state tried vainly to exercise some control, the mills have had to pay the price set by the market.

The market price stays high mostly because China’s steel industry depends on its own domestic iron ore mines for about 20% of their supplies. They are high-cost operations and high prices are required to keep them in business. In a competitive commodity market, prices for everyone are set by the highest cost marginal producer.

China’s central economic body, the National Development and Reform Commission, is blaming ‘speculation’ and ‘hoarding’ of iron ore stocks for the latest price surge and is promising tighter supervision of futures markets, however such measures are unlikely to have any more effect now than they have in the past.

Beijing’s efforts to reduce dependence on Australia include supporting the expansion of its domestic iron ore mining, increasing its use of scrap steel and investments in Africa. These efforts have been underway for the past decade during which its dependence on Australia has actually increased.

The Simandou project in Guinea is the most significant new iron ore development globally. It faces formidable technical, logistical and political challenges, but the project is moving ahead. For political reasons, the rail route must be open to general rail traffic through central Ghana. Shipping more than 1 million tonnes of iron ore a week along a rail line used for passengers and general cargo will be a logistical nightmare.

More non-Australian supply will emerge over coming years but any significant fall in the iron ore price is more likely to result from weaker Chinese demand. Many expected that the downturn in its housing sector, which has historically been the source of about 40% of China’s steel usage, would bring the miners’ super-profits to an end. However, there has been enough growth in industrial and infrastructure activity to offset the weakness in residential construction, even in the absence of the massive stimulus programs used to fight past downturns.

The China-powered iron ore markets are contributing to Australia’s unexpected federal budget surpluses. Australia’s Treasury has, in each of its last 10 budgets, predicted that iron ore prices would drop back from market prices usually well above US$100 a tonne to US$55 or (in its latest budget) $US60. Every US$10 in the iron ore price that Treasury gets wrong translates to a A$500 million error in its annual budget balance.

Treasury will eventually be right, but in the meantime Australian living standards will continue to be supported by China’s need for our iron ore.

The hack into the systems of ports operator DP World at the weekend exposes Australia’s high dependence on containerised imports for manufactured goods.

Walk into any Bunnings, Harvey Norman, Officeworks, Myers or K-Mart store, and nearly everything you see has been imported in a container.

Australia’s own manufacturing sector, which still employs just under a million people and accounts for about 5.5% of the economy, similarly depends on imports packed into containers for a large share of its inputs, from the nuts and bolts to the pumps, motors and fabricated-metal products.

The Australian Financial Review cited estimates that the forced shutdown of the system managing DP World’s interface with trucking carriers resulted in about 30,000 containers being stranded, with trucks unable to get containers into its parks or out.

While the container shipping industry is crucial to Australia, we are a relatively unimportant to it, representing a small share of the global trade. Almost half of the containers that arrive in Australia full are returned empty.

The advent of the shipping container was one of the driving forces of globalisation, vastly increasing the ease of loading and unloading ships and integrating maritime and land transport. In 1990, about 200 million tonnes of goods were carried globally by container. By 2021, that had risen to just under 2 billion tonnes.

China is the behemoth of container shipping. Of the world’s top 100 container ports, according to a list compiled by Lloyd’s List in London, 24 are Chinese. Combined, they handle the equivalent of 260 million 20-foot containers a year.

Ports in the North Asian manufacturing centres of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong handle 80 million containers a year, while the Southeast Asian ports are responsible for a further 100 million.

Although Australia is highly dependent on containerised shipping, it is ports are small by global standards. In 2022, Melbourne ranked 62nd on the global list, handling 3.3 million containers, and Sydney, ranking 76th, handled 2.8 million. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Australia accounts for 1.1% of global container throughput.

The shipping navigation website VesselFinder shows that, at present, there are about 70 container ships either heading for Australia or berthed in one of our container ports. Most are coming from North Asia—China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong; the other main originating ports are in Singapore and Malaysia.

Container ships do regular rotations through the Australian ports. In 2020–21, there were 311 container ships doing the Australian run, making a total of 1,484 visits to country with 3,705 port calls, according to data compiled by the Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics. The average ship carries about 4,600 containers (based on the standard 20-foot container measure).

The port operators provide the link between the shipping and land transport. Ships book a slot at one of their wharves, the containers are moved to parks, and trucking carriers book to collect their containers once they have been cleared by customs. It is a technology-intensive business, with systems to manage the physical booking of wharf and crane slots, container park storage and trucks, as well as the documentation of container contents.

DP World and Patrick Terminals both operate container terminals in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and Fremantle. Hutchison Ports has terminals in Brisbane and Sydney, Victoria International Container Terminal has one in Melbourne and Flinders Adelaide has the monopoly in Adelaide. The five capital city container ports handle about 92% of container throughput, with small volumes at Darwin, Townsville and Bell Bay.

An insight into the extent of Australia’s reliance on shipped manufactured imports is given by the database of port-to-port trade compiled by the Australian Border Force. Just in the month of July 2023, 113,000 consignments were imported to Australia by sea at a cost of $27.8 billion.

Of those, 31,100 came from China, with a total cost (including freight) of $7.3 billion. There were 4,720 consignments from Japan, worth $2.5 billion, and 2,180 from South Korea, worth $1.4 billion. They cover a vast variety of industrial inputs and consumer goods that find their way into every nook and cranny of the economy.

The Productivity Commission’s recent inquiry into Australia’s maritime logistics system noted that cargo flows involved almost 3,000 uniquely identified commodities. More than 40% of them involve the trade each year of less than 1,000 tonnes, equivalent to about 70 container loads.

While Australia’s imports mainly arrive in containers, bulk carriers are used to ship most of our exports, whether that’s resources like iron ore or agricultural commodities like barley and wheat. The same trade database shows 27,800 export consignments in July, of which 10,000 represented mineral or agricultural commodities most likely to be shipped in bulk. Together they represented almost 90% of the value of exports.

Some export agricultural commodities, like wool and cotton, are packed in containers, while meat and dairy products are shipped in refrigerated containers. Resource commodities like aluminium ingot can also shipped by container. However, Australia’s containerised manufactured goods are small relative to imports.

Australia and New Zealand are a special run for the shipping lines—they’re not on the way to anywhere. A central feature of globalisation is the manufacture of goods across several nations, but Australia has little participation in these global supply lines. Parts made in Australia for the F-35 fighters and for Boeing are an exception.

UNCTAD measures how connected a country’s container shipping is to other nations and compiles an index based on the number of ship calls, their carrying capacity, the number of liner companies servicing the country and the number of other countries connected through direct liner shipping services.

China tops the ranking, followed by South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and the United States. Australia’s score has been improving, but it ranks a lowly 57th, just ahead of Argentina and the Congo, but below Togo, Chile and the Ivory Coast.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Beijing in June exposed the scarcity of military-to-military dialogue between China’s People’s Liberation Army and the US military. Stabilising US–China relations to manage competition and avoid conflict was the main goal of Blinken’s visit.

Despite echoing these aims in its propaganda, Beijing has closed military-to-military channels at the same time that the PLA is ramping up assertive manoeuvres against US assets in the Indo-Pacific, raising the risk of potentially fatal miscalculations and accidents. These channels could mean the difference between peace and war.

The PLA is the Chinese Communist Party’s military arm. Article 29 of the Chinese constitution states that the armed services ‘belong to the people’, yet CCP Secretary General and Chinese President Xi Jinping reiterated to the 20th Party National Congress the importance of ‘absolute leadership of the party over the people’s army’. As chair of the Central Military Commission, Xi is paramount commander of the PLA—itself a branch of the party, not the Chinese state.

That might sound similar to the principle of civilian control over the military familiar in the West, including the US president’s role as commander-in-chief, but these parallels are misleading. Xi commands without the checks and balances central to constitutional democracy. The CCP extends its control over the PLA at every level of command through the ‘military and political dual-command structure’ (军政双首长制).

Quoting Mao Zedong at the PLA’s 90th anniversary celebration in 2017, Xi reminded the armed forces that ‘our principle is that the party commands the gun, but the gun is never allowed to command the party’. The CCP uses political organisations to avoid corruption, revolution and dissension in the PLA, and officials have noted the importance of the dual-command structure in ‘fully implementing and embodying the fundamental principle of the absolute leadership of the party over the people’s army’.

While a dual-command structure will be unfamiliar to most associated with Western-style militaries, it is imperative to understanding China’s ‘people’s army’. So what is it? And why does the CCP think it is the PLA’s ‘greatest characteristic and advantage’ compared to the West’s single-command structure (一长制)?

Essentially, the PLA reports to the rest of the CCP at every level of command. The party uses a handful of political organisations in the PLA, additional to the military’s command structure, to keep it under control. The political commissar at one of China’s top defence universities has said that these organisations—namely, the party committee system (党委制), the political commissar system (政治委员制) and the political organ system (政治机关制)—represent the CCP‘s ‘painstaking exploration and development and gradual finalisation in the process of ideologically building the party and politically building the army’. These are the three foundational political structures at the heart of the dual-command structure.

The party committee system is the ‘fundamental system of the party’s leadership of the people’s army’. Party committees lead and guide the work of the party at every military level; they also function outside the PLA in all aspects of society. The CCP sees committees as crucial to a ‘unified system of division of responsibility among heads under the unified collective leadership of the party committee’ (党委统一的集体领导下的首长分工负责制). While a mouthful, the phrase strikes on the CCP idea of ‘collective leadership’ (集体领导) that’s at the core of the dual-command structure securing the rest of the party’s control of the PLA.

The second pillar of the dual-command structure is the political commissar system. A PLA political commissar (政治委员) acts as the ‘head of his unit along with the military commander at the same level and is jointly responsible for the work of the troops to which he belongs under the leadership of the party committee at the same level’. The commissars lead and organise the political work of units, including education. Since they act at the same level with similar authority as their corresponding military commanders, they are integral to the dual-command structure of the PLA.

Political commissars also play a role managing discipline, morale and welfare, a function usually filled by higher-ranking enlisted soldiers in Western militaries. Political commissars’ specific roles can vary—at lower levels they are designated as directors and instructors—but they have similar responsibilities.

The third pillar, the political organ system, comprises ‘administrative and functional’ departments that host political work at each level of the military. While little is known about exactly how they function, the role of the political organs is hold the PLA accountable to political objectives through inspection and punishments. (The word ‘organ’ is the Chinese ji’guan (机关), which can also be translated as ‘institution’ or ‘agency’.)

Using these systems, the dual-command structure provides political command that sits alongside the operational command of military personnel. Since the PLA’s official creation on 1 August 1927, there was only one short period in the late 1930s when it didn’t have a dual-command structure. After an almost immediate increase in disloyalty, Mao quickly reversed the decision and reinstated PLA political organisations.

From the Western perspective, a collective leadership system like this would seem to weaken the PLA’s ability to make good decisions quickly. Its advantage, however, is complete political alignment and, ideally, prevention of corruption. The dual-command structure can secure party loyalty with little room for error, but at some point the party is making a trade-off, be it for speed of communication, innovation or intent. The Western military mind is immediately drawn to the limitations of collective leadership, but without a real test we will never know for sure where those limitations might lie, or how restrictive they might be.

While understanding the PLA’s dual-command structure is a great start, viewing the PLA as one might view a Western military is the wrong approach. When considering the PLA’s structure, Western leaders must keep in mind what it is—the armed wing of the CCP. It is a civil-war-born military that exists to hold political power for the party. The dual-command structure is not just a quirk of command-and-control tactics; it’s integral to the PLA’s purpose.

In the CCP’s eyes, the PLA’s dual-command structure is just as efficient and powerful as a Western military’s command system, if not better. Above all, if strategists cannot prevent themselves from projecting their Western-style military perspectives onto the PLA, they risk severely misunderstanding the CCP’s lethal arm, and will pay the price for it.

With all that’s going on in the world, you could be forgiven for missing that the 10th anniversary forum of Xi Jinping’s flagship foreign policy and trade program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was held in Beijing in the middle of last week. Some saw the West’s involvement in conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine as creating a strategic opening for Chinese diplomacy at the forum. But that’s a misreading of China’s public diplomacy goals and a far too rosy view of how last week’s event actually went.

China wants the world to value the BRI and to view China as a legitimate leader of nations in global development. As an initiative that Xi himself proposed in 2013, its success is directly linked to his power as a leader.

Beijing saw this forum as a crucial chance to advocate for its ‘global community of shared future’ proposal. In the run-up, it released a white paper outlining how this proposal could lead to a new type of international relations that rejects the Western-led multilateral order and its emphasis on ‘universal values’. It also published a white paper on the BRI, positioning it as a core pillar of the ‘global community of shared future’ proposal. Xi’s keynote address at the conference focused on lauding the achievements of the first 10 years of the BRI and how following China’s development path through the ‘global community of shared future’ was the best way towards world peace and prosperity.

This message fell on deaf ears. Chinese state media reported that representatives from more than 140 countries attended the event, but, in fact, only 21 countries sent representatives at the head-of-state level. That’s the lowest ever attendance of heads of state at a BRI forum. Notably, the leaders of Brazil, India and South Africa—which, along with Russia and China, comprise BRICS—were absent.

In a telling contrast, Fiji’s Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka chose to make a state visit to Australia last week rather than attend the forum, sending his deputy to China instead. No bilateral BRI projects between China and Fiji were announced at the forum, whereas Australia announced a new pathway to permanent residency for citizens of the Pacific island countries and Timor-Leste. This is something China would never be able to offer the Pacific and addresses a genuine policy want from countries in the region.

China also made a public diplomacy blunder in giving Russian President Vladmir Putin top billing at the forum. Putin appeared next to Xi in the leader’s photo and was given the most important position after Xi as a keynote speaker. While we should worry about the strengthening Sino-Russian ‘no limits’ partnership, Russia isn’t even formally part of the BRI. Rather than emphasising strength and unity, giving Putin such a prominent role instead undercut China’s claims to multilateralism and anti-hegemony. That’s not to mention the image problems China has from its support of another rogue actor, the Taliban, who were invited to attend the forum and have been encouraged to join the BRI.

Many countries may have sent representatives to the forum as a way to maintain good relations with China, but not to further deepen their engagement with the BRI. With many Chinese development banks and financing institutions in attendance, countries with large BRI projects may have also used it as an opportunity to negotiate their existing financial agreements with China, rather than sign on to new deals. Indeed, Sri Lanka, which owes Chinese lenders more than US$7 billion, had its president advocating that a lack of debt relief for low-income countries posed an existential risk to the BRI.

In analysing where the BRI is going, we should look at what China does, not what it says. Major BRI projects are typically announced in an outcomes document from the forum, and an analysis of this year’s outcomes show a gap between what China says its new vision for the BRI is and what it is actually funding. Most projects in the list are not new deals and had already been announced prior to the forum. For example, the document announced that China would build the Solomon Islands’ national broadband network, although the deal was already signed more than a year ago. Similarly, China said it would construct the Kaduna–Kano railway in Nigeria, but ground was already broken on the project in mid-2021.

At the forum, Xi announced that ‘green development’ in the BRI would be a major step in the initiative, and early analysis has noted that the BRI will now be ‘smaller and greener’. While several renewable energy projects were announced, analysis of the outcomes document shows that the dominant type of project in the BRI still appears to be infrastructure, such as railways, ports, airports and sports stadiums. And as much as Xi’s speeches at the conference repeatedly emphasised his new focus on ‘high-quality’ Belt and Road cooperation, China will still have to manage a hefty legacy portfolio of large and not-so-high-quality projects like the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka and the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor.

With close to US$1 trillion in funding granted over the years, the BRI remains a formidable tool of economic statecraft for China to pursue its foreign policy and security ambitions. But the poor attendance of world leaders at last week’s forum and the lack of international attention paid to it would be far from what Xi feels his initiative deserves.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria