In a decade of danger, it’s time to prepare civil defence

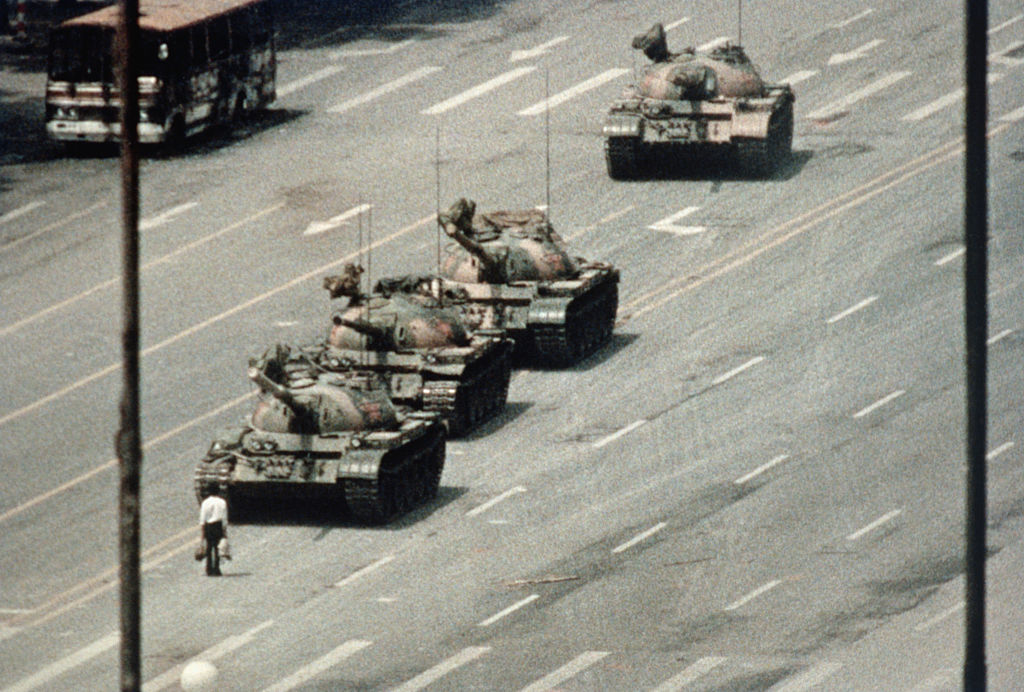

Humanity again finds itself in an age of war. European political and military leaders speak increasingly of being in a ‘pre-war’ period. Worrying signs abound of an impending major war in the Middle East. From the northern territories of Japan, across to the Korean peninsula, through the western Pacific, and around to the disputed border of China and India in the Himalayas, there simmer flashpoints which could erupt into wars in Asia.

Our worst nightmare would be for different wars in Europe, the Middle East and Asia to break out and merge into a third global war for supremacy in Eurasia, the geostrategic heartland of the world. Such a war would perhaps be humanity’s last.

What might this mean for the defence of Australia? Our defence planners are rightly focused on a wide variety of contingencies. With very little notice, the Australian Defence Force could be called upon to undertake rapid deployments in the nearby arc of small states. While necessary and important, such ventures would be only marginally relevant to today’s great issues of war and peace. The same could be said of vital operations in support of distressed communities in the wake of natural disasters.

Given long-lead times, Defence also has to focus on complex capability and programming issues, especially as related to the planned force of 2035 and beyond. However, just as defence planners of the late 1930s would have found, perhaps when contemplating the optimal force of 1955, more pressing matters can arise suddenly.

Certainly, our strategic imagination has to be cast forward a decade or more. In doing so, we should contemplate very different possible futures—including where perhaps the United States had isolated itself (as a matter of choice or through military defeat); where China was hegemonically dominant in the Indo-Pacific; and perhaps where a very different Indonesia was able and inclined to directly threaten Australia. In these presently improbable futures, a very different defence force would have to be imagined, based on a large navy and air force, heightened military preparedness, and a defence budget amounting to 5 to 6 percent of GDP, if not more. Without the protection afforded by extended deterrence, we would struggle to deter attacks by nuclear-armed adversaries.

These different futures are worthy of contemplation. The times, however, demand that we devote the greatest amount of useful effort to more immediate challenges. We face, before 2030, the credible prospect of having to defend Australia during a major war in the Indo-Pacific. Australian defence planning has since the Second World War rarely focused on the idea of mounting such a defence. Planning until the mid-1970s typically contemplated instead ‘forward defence’ —sending Australian military forces forward into Southeast Asia. During the 1970s, the idea of the ‘defence of Australia’ emerged. The concept, as announced in the 1987 Defence White Paper, contemplated low-level attacks, to be handled in a largely self-reliant fashion. This was good policy for the times.

Today, we need to contemplate Australia, and the airspace, seas and islands that surround us, as potentially constituting a theatre in a larger Indo-Pacific war. How or why such a war might come about would require a lengthier analysis. For the sake of discussion, and planning, it would be prudent to rate the chance of war breaking out in the Indo-Pacific in the 2020s at 10 percent, at a minimum. Such a war could well be drawn out over months as the combatants carefully sought to avoid strategic nuclear escalation, an assumption which needs to be critically examined at another time.

Unless Australia were to actively decline to take part in such a war, including by way of denying to the United States access to the use of facilities in Australia, then it would be reasonable to assume that an adversary would contemplate actions to degrade our ability to support the US war effort, and to undermine the national will to fight. It is probable that we would face, at a minimum, cyberattacks on critical infrastructure and essential services. Cognitive warfare would be employed, using technology-enabled propaganda and disinformation, which would be aimed at degrading Australia’s national will. We could not rule out the possibility of more direct action also being taken.

From the perspective of the United States, Australia would be viewed as the vital southern bastion in any such war, in relation to a number of publicly declared intelligence, surveillance, communications and space activities; in support of potential US operations in the South China Sea, the South Pacific, and the Indian Ocean; as a haven for the dispersal of at-risk US forces; and as a logistics, maintenance and sustainment support base. There would probably be an expectation that Australia would lead in its home theatre, without unduly calling on US assistance, especially were stretched US forces to be engaged simultaneously in combat operations in Europe and the Middle East, as well as in the Indo-Pacific. Were it come to pass, we should indeed insist on Australian primacy in our theatre (in contrast to our subordination in 1942–45), with any available allied forces being integrated into Australian-led theatre-level forces.

Defence of the Australian theatre would be a higher priority than sending our forces forward, except for perhaps some on a limited scale, and would represent our principal contribution to the war effort. This would also be central to the adversary’s calculations about whether, when and where to strike us, and how heavily. This would have implications for the ADF’s force structure and how we might employ it operationally—with the priority being to develop an integrated and focused force which was optimised for a campaign on and around our territory and in the broader airspace, seas and islands of a theatre-wide area of operations.

Civil preparedness would also be required. Civil defence and national mobilisation would be intrinsic to any war effort. If the possibility of war in the Indo-Pacific is to be taken seriously, relevant preparations should be made urgently, but also proportionately and soberly. In war, the most important question is whether the nation at large has the structures, capabilities and, above all, the mindset and national will that are required to fight and keep fighting; and to absorb, recover, endure, and prevail. These cannot be put in place or engendered on the eve of the storm.

With the exception of brief periods during the Cold War, civil defence and national mobilisation have not been priorities for Australia since the Second World War, because wars, such as were being fought, were remote from Australia and not directly threatening to our population or territory. Today, war could come to our home, and potentially for an extended period.

As a practical suggestion to focus effort, we should modernise the practice from the 1930s and the 1950s of the preparation of a war book.

War books were guides on what would need to be done, and by whom, in the event of war. Preparing a modern war book would help to focus the national mind, break down the abstraction of ‘war’ into its particulars, enhance preparedness and contribute to resilience.

A war book would be prepared by the Commonwealth, with contributions from the states and territories. As our society is today more dependent on private companies to operate critical infrastructure and deliver essential services, business would have to be deeply involved from the outset. Unlike earlier iterations, which were controlled by the Department of Defence, a modern war book would be best prepared jointly by Defence and the Department of Home Affairs, the latter as a consequence of the crucial role that would be played by critical infrastructure providers, cybersecurity firms and emergency management bodies in any war effort. Other departments and agencies would be brought into the process, which Home Affairs could coordinate, as it did during the pandemic.

A war book would deal with the entire span of civil defence and national mobilisation which would be required to move to a war footing, consisting of a range of coordinated plans. Some would deal with critical infrastructure protection and national cyber defence. Others with the mobilisation of labour and industry (covering supply chains, industrial materials, chemicals, minerals and so on). Sectoral plans would address the allocation, rationing, and/or stockpiling of fuel, energy, water, food, transport, shipping, aviation, communications, health services and pharmaceuticals, building and construction resources, and so on. There would be plans for the protection of the civilian population (covering evacuation, fortification and/or shelter construction); for augmenting police, fire, rescue and ambulance capacities; and dealing with social cohesion, domestic security and public safety.

Lessons could be adapted from international experience (especially Ukraine and Israel), as well as domestic experiences, such as natural disasters and the COVID pandemic, noting however that war is different insofar as in war a conscious adversary calibrates and adjusts their actions as the situation unfolds. War is not simply another hazard in the all-hazards universe of emergency management. It has its own character and logic. We need to think about war as a national crisis unlike any other.

A war book would deal with legal authorities, which past experience would suggest would have to be urgently expanded in a war. The defence power in the Constitution has been successfully used in the past to ground otherwise impermissible authorities (for example to do with rationing and prices). The relevant constitutional cases were decided in the 1940s. Fresh thinking would be required to test those earlier concepts and to inform the drafting of contingency legislation, which could be prepared in readiness.

A complex area which would need careful thought would be cognitive warfare. A war book could usefully set out roles and responsibilities for dealing with disinformation and propaganda, and especially the vexed questions of censorship (to protect the war effort) and government information processes to thwart an adversary’s efforts to deceive and demoralise the population. Technologies and procedures would need to be developed, as required, to disseminate alerts, notifications and public information regarding developments in the war, in trusted and secure ways.

The whole point of this exercise would not be the production of a competently produced technocratic document, as useful as that might be. A war book would of itself simply consist of building blocks (the plans) that could be quickly activated should the need ever arise, tailored to circumstances as they emerged.

More importantly, the very act of undertaking such planning would of itself enhance preparedness and resilience, as relevant experts were brought together to develop solutions through a structured process—for instance, to deal with the likelihood that Australia’s international shipping and aviation links would be impaired severely, or cut completely, in such a war. Developing civil defence and mobilisation plans would force us to think expansively and intensively, concretely and innovatively, and above all collectively.

If done well, it could be used to sensibly bring the nation along, with purpose, focus and structure, and without undue alarm. Secrets would still have to be preserved, and sensitive details would need to be protected. Through such an effort, those with ears to hear would come to understand what needs to be done in the face of what might come.

In an era of labels, reductive discourse, and short attention spans, these remarks will be dismissed as ‘predictably hawkish utterances’. Surely, we can be more nuanced and layered. Preparing our society and economy for the contingency of major war would be complementary to, and supportive of, a strategy of working to defuse tensions and ensure peace. Engaging in diplomacy, seeking to stabilise international relationships, and reducing the margin for miscalculation are not idealistic follies. They are the realist’s approach, if only to buy time, while preparing simultaneously for the possibility that such efforts might yet fail. If this is indeed a pre-war period, we should redouble all efforts to ensure peace while at the same time preparing resolutely, without reducing every suggestion to the binary opposition of ‘hawk’ or ‘dove’.