Asia in 2014

We enter 2014 with the Asian security mosaic as complicated as it’s been in a long while. The two rising regional great powers, China and India, are still rising but at least in China’s case growth is slowing. The region’s stalled great power, Japan, is making a solid effort to get its motor running again. Russia is probably still a declining power, at least as far as Asia and the Pacific are concerned, but it’s modernising its nuclear forces and playing its foreign policy cards more adroitly. Kim Jong-un’s North Korea remains a regional wild card, the country’s nuclear program accelerating even as its domestic politics become more brutal and less certain. The region’s second-tier powers—and here we could reasonably count South Korea, Indonesia, Australia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam—add their own complexities to the mix. And that’s before we even get to the United States.

We enter 2014 with the Asian security mosaic as complicated as it’s been in a long while. The two rising regional great powers, China and India, are still rising but at least in China’s case growth is slowing. The region’s stalled great power, Japan, is making a solid effort to get its motor running again. Russia is probably still a declining power, at least as far as Asia and the Pacific are concerned, but it’s modernising its nuclear forces and playing its foreign policy cards more adroitly. Kim Jong-un’s North Korea remains a regional wild card, the country’s nuclear program accelerating even as its domestic politics become more brutal and less certain. The region’s second-tier powers—and here we could reasonably count South Korea, Indonesia, Australia, Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam—add their own complexities to the mix. And that’s before we even get to the United States.

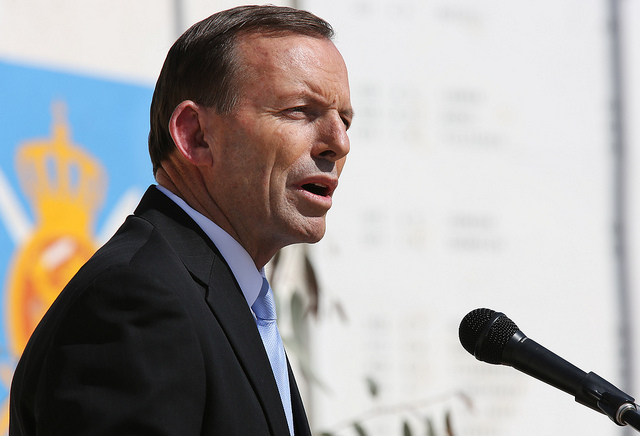

We’re approaching the one-year anniversary of the beginning of President Obama’s second term. And, speaking plainly, I don’t think it has started well. The noted Asia hands of his first administration—people like Kurt Campbell and Jim Steinberg—have left. True, Joe Biden (the Vice President) and Susan Rice (the National Security Adviser) have both delivered big set-piece speeches on Asia. And the rebalance remains the core of US Asia policy—even though Asian audiences are still trying to decide what it actually means. Meanwhile two US decisions about the Middle East—the handling of the Syrian chemical-weapons issue and the Iranian nuclear agreement—have both muddied the waters in US relations with Asia. The first showed a hesitancy in US willingness to use force; the second a US willingness (actually a P5+1 willingness) to accept a quasi-nuclear status for Tehran. Both decisions have generated ripples in our own region.