America’s AIIB fiasco: the perfect storm (in a teacup)

A month ago, Stewart Patrick from the Council on Foreign Relations described the move by France, Germany, Italy and the UK to become founding members of the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as a ‘body blow to the US-led international order created in the wake of World War II, which is crumbling before our eyes.’

A month ago, Stewart Patrick from the Council on Foreign Relations described the move by France, Germany, Italy and the UK to become founding members of the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as a ‘body blow to the US-led international order created in the wake of World War II, which is crumbling before our eyes.’

Few other analysts have been quite as gloomy. Most accounts of Australia’s belated decision to dip a toe in the water suggest the benefits of getting involved will outweigh the costs of not participating. According to that logic, the more Western shareholders with ‘seats at the table’ from the start, the less risk the new bank will adopt opaque governance structures or support Chinese political and business interests. A multilateral commercial bank like AIIB that makes bad lending decisions due to poor procedures would find itself in trouble faster than alternatives like China’s Silk Road Fund. The bank might even give Beijing a responsible stake in international public goods where there’s an $8 trillion need.

Australia’s last-minute scramble to make the AIIB’s cut-off date was inelegant. But while following the herd wouldn’t have burnished our reputation with either Washington or Beijing last month, at least it underlines to both where we sit. Hugh White’s ‘China Choice’ is principally a matter for Washington, not Canberra. There’d be little to be gained in trying to act as a trusted bridge between the two countries: inserting ourselves wouldn’t assist their clear communication but would imply an unhelpful equivalence.

Hugh regards the AIIB’s fairly graceful lift-off as a more significant milestone than do most, especially given America’s awkward effort to prevent it. He calls the AIIB debacle a ‘wakeup call for Washington’ as America’s China consensus slowly unravels. The episode fits the stark choice he sees between the US acknowledging China as an equal and yielding commensurate space or else trying to contain it in order to preserve American primacy.

I’d agree that the AIIB’s launch was significant. Sure, its US$50 to US$100 billion capital isn’t about to dominate international finance flows; America’s Bretton Woods institutions are far from the only basis of US predominance; and even rusted-on allies like Australia have failed to follow the US lead before (Graeme Dobell points approvingly to John Howard’s rejection of the IMF’s harsh medicine during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis). It’s rare, though, to see so many close friends reject US overtures so quickly and utterly. Beijing’s success attracting donors over Washington’s objections may be ‘mainly symbolic’ but symbolism counts in the race for global influence—zero sum or not.

Still, I’d describe Washington’s ‘AIIB fiasco’ as more of a snafu than a watershed, and expect the upshot will be a case of America doing the right thing—after exhausting every alternative rather than radically changing policy direction.

As the US measures the harm it’s inflicted on itself, some blame the ‘imperial hubris’ of an administration that should have learned not to make such rigid demands after its experience with its Syrian red-lines. But there’s been more hand-wringing than finger-pointing as the chief cause is ultimately a level of gridlock no one can be too proud of. Since 2010 Congress has blocked reforms that would have allowed China to play the larger role it sought in the World Bank and IMF. While that mightn’t have prevented Beijing from wanting to establish an AIIB, it could have at least provided the US with a leg to stand on in opposing its creation. Instead, stymieing the reforms can only have strengthened China’s ‘if you can’t join ‘em, beat ‘em’ logic.

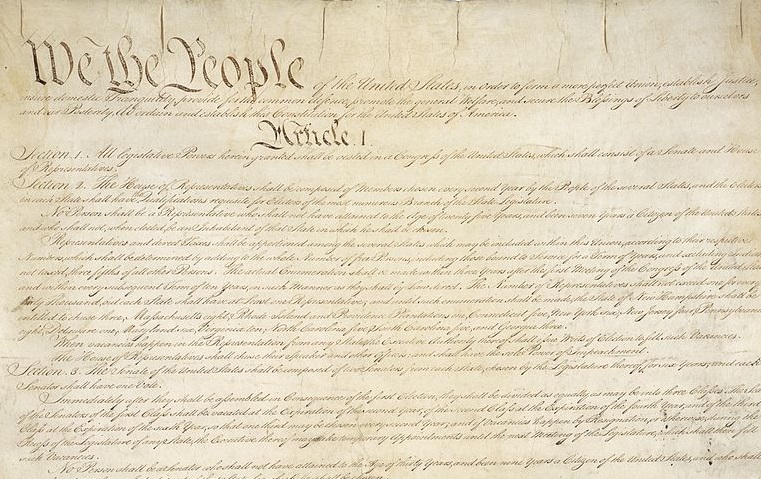

It’s tempting, then, to view the US government as so bitterly divided that it’s ‘on the verge of ceding the global economic stage’ and legitimacy it built at the end of the Second World War to the rising powers. The sharp drop-off in treaties being approved by the Senate during the current administration, reckless intransigence of Tea Party insurrectionaries, and recent spectacles such as sequestration might seem to support that concern. Yet neither US exceptionalism nor robust partisan wrangling are at all unprecedented. Presidents have grumbled about the Senate obstructing the executive’s foreign prerogative since George Washington’s time. The Senate famously rejected Woodrow Wilson’s Versailles peace treaty because it might bind Congress’ war-making powers to League of Nations decisions rather than because it seemed overly punitive. And during the George W. Bush era, the Senate twice refused to approve the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (which the US follows in practice, and might provide useful normative leverage against China’s maritime claims) despite strong administration support.

Although none of those examples offer cause for cheer, they remind us that domestic politics always shape the foreign commitments of democracies, and that US power has continued to grow through periodic past reverses. While it’s unrealistic to expect an end to political dysfunction anytime soon, President Obama has used executive agreements as effective tools to move his agenda forward. And there are signs Congress is getting closer to granting Trade Promotion (‘fast track’) Authority where it really counts: for Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations at the heart of the rebalance.

Rather than hoping the AIIB episode will spur Washington to seek a grand settlement with Beijing, we should expect regular historical jiggling to continue apace—between businesses, unions and parties, among others, domestically, and states, corporations, and competing trade blocs internationally. There we’ll have much to be thankful for, given the importance of accommodating China’s rise, if America’s AIIB-rout encourages it to play its strong hand a bit smarter.