‘Forward defence in depth’ for Australia (part 1)

In an interesting, and highly significant, recent statement, China’s Foreign Affairs spokesman, Lu Kang, challenged Australia’s traditional perception that the South Pacific is within its sphere of influence. He stated that, ‘The Pacific islands are no “sphere of influence” for any country’, and employed the traditional rhetoric of Chinese government communiqués, asserting, ‘We hope that the relevant parties could discard the outdated mindsets of Cold War mentality and zero-sum game [and] objectively view China’s relations with Pacific island countries.’

The reality, of course, is that China is determined to challenge the US’s strategic primacy across the Indo-Pacific, and seeks to replace the established rules-based order with a Chinese-led system that would diminish, and then ultimately eliminate, America’s influence in Asia. China’s increasing involvement in the South Pacific through the Belt and Road Initiative is an important component of the emerging strategic contest and a challenge to Australian security.

Those signing up to the BRI (the Victorian government should take note) must understand that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Small states in the South Pacific, burdened with Chinese debt they can’t pay back, risk watching as China’s presence grows in their countries through its investment in infrastructure projects that, ultimately, it will control, once the debt trap is sprung.

Most worryingly for Australia, the BRI opens up the potential for a Chinese military presence in territories close to our eastern seaboard. Such a development would give Beijing greater opportunity for military coercion against Australia in a crisis.

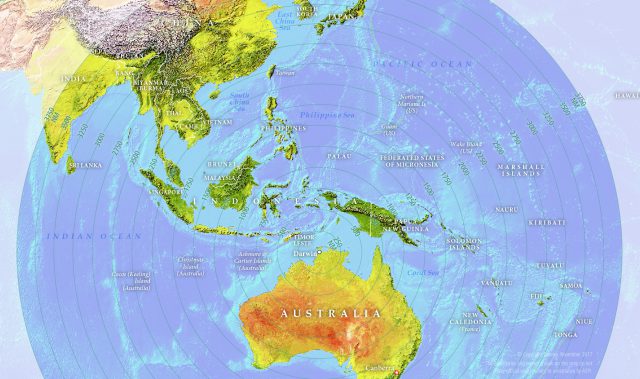

Given the risk a forward Chinese military presence would pose, Australia needs to consider updating its military strategy to one of ‘forward defence in depth’ throughout Indo-Pacific Asia, including into the South Pacific. Australia should not maintain a reactive military strategy that continues to rest on foundations established in the mid-1980s when our strategic outlook was far more benign.

Forward defence in depth builds on the strategy outlined in the 2016 defence white paper that was centred on three strategic defence objectives:

- deter, deny and defeat attacks on or threats to Australia and its national interests, including incursions into its air, sea and northern approaches

- make effective military contributions to support the security of maritime Southeast Asia and support the governments of Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste and Pacific island countries to build and strengthen their security

- contribute military capabilities to global operations that support Australia’s interests in a rules-based international order.

Forward defence in depth would integrate the first objective—essentially the ‘defence of Australia’ mission—with the second objective by giving the ADF a far more visible and regular role throughout maritime Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. In doing so, we’d extend our defence in depth far forward, rather than basing the defence of Australia task on being able to defend a comparatively narrow strategic moat that is the ‘sea–air gap’. The third objective—more far-flung operations in support of a global rules-based order—should be prioritised to contingencies across the Indo-Pacific region. The objective of forward defence in depth is to expand our regular military presence and meet any threats that emerge much further from Australia’s shores.

This is not meant to discount the requirement or significance of Australia’s vast inland areas as a natural defensive advantage. One of the main reasons Australia has never been invaded is because of the vast and hostile terrain between our northern coasts and our southern population centres. But defence infrastructure in our north is too sparsely deployed and too limited. It’s a very thin front line with very long internal lines of supply to southern defence infrastructure and force concentrations. That posture is increasingly in need of review.

In an age of new types of weapons and new types of warfare, it’s not at all clear that the sea–air gap gives Australia the same advantage as it did in the days of the Paul Dibb’s 1986 review of defence capabilities or the 1987 defence white paper when the threat environment was drastically different.

A forward Chinese military presence would fundamentally change our strategic calculus for the worse. It could come both from forward military bases of the sort seen now on disputed rocks and reefs in the South China Sea, and dual-use facilities like Hambantota in Sri Lanka. That would enable China to concentrate its military power in a way that puts our northern bases at risk in a crisis—particularly if their defence rests on responding only if an opponent enters our northern air and maritime approaches, as suggested in the 2016 defence white paper.

That approach rests on assumptions about the strategic geography of a ‘land girt by sea’ offering us a decisive defensive advantage. Yet the growth of long-range cruise- and ballistic-missile capabilities and the emerging threat of hypersonic weapons, cyberattacks and anti-satellite weapons make new types of coercion possible that simply bypasses the strategic moat to our north. It also fails as a credible response to the ability of the Chinese navy to interdict our vital offshore fuel and energy lifelines, which all traverse chokepoints and narrows in maritime Southeast Asia. A policy based on defending the sea–air gap could potentially become the Maginot Line of the 21st century.

Forward defence in depth develops and extends an ADF anti-access and area denial (A2AD) perimeter outwards. It denies a peer adversary a cost-free ability to manoeuvre close to Australia and exploit long-range strike weapons effectively or threaten our energy security. It shifts our strategy to be more in line with 21st-century multi-domain operations and emphasises a requirement for the ADF to become a power-projection force in every sense.

It also allows us to strengthen cooperation with the US and do more to share the burden with our essential strategic partner, while opening up new opportunities for greater defence cooperation with key partners across the Indo-Pacific and into the South Pacific. The recent agreement by the US, Australia and Papua New Guinea to develop the Lombrum naval base at Manus Island is an excellent start, but that defence diplomacy needs to go much further.

In the second part of this series, I’ll consider the importance of strengthening defence diplomacy and economic relationships with our key regional partners, and then conclude in the third part with suggested enhancements to ADF force structure.