Morrison’s middle-power mateship

How times change. Only half a century or so ago, Australians were fighting and dying in Vietnam in an American-led effort to hold back the supposed threat of communist expansion. The whole of Southeast Asia would fall over like so many dominoes, we were assured, unless young Australian men risked their lives to stop them. Now the very same ‘communist’ government, which eventually won the war, is now our newest ‘mate’ in the region.

You don’t have to be a relative of one of the 500 or so Australians who died in Vietnam to wonder what’s going on here. What vital national interest did these young men give their lives for? Even the former head of the Australian Defence Force, General Peter Cosgrove, has conceded that Australia’s participation in this conflict was ‘a mistake’. It is, of course, not the last one Australian policymakers and planners have made when acting in support of the alliance with the United States.

Nor is it necessary to rehearse the well-known and catastrophic history of the invasion of Iraq to make a simple point: that war was also one in which Australia’s vital strategic interests were arguably not involved and which contributed absolutely nothing to the safety of the nation. And yet our predictable support of American foolishness contributed to a tragedy that has yet to finish playing itself out.

Even if we put to one side the appalling and avoidable loss of human life, strategic hardheads would have to concede that the destabilisation of the entire Middle East has profoundly undermined international security generally. It has also encouraged our ‘great and powerful friend’ to make an all-too-predictable request for participation in yet another ill-judged and potentially calamitous foreign adventure with little immediate relevance to Australia.

Equally predictably, the Morrison government has agreed to cooperate. That this contribution has been dressed up as part of a supposedly international effort—and not slavish devotion to the alliance—doesn’t make it look any less like just another outing of the usual Anglosphere suspects. The phrase lipstick on a pig comes to mind.

If this is a depressingly familiar story and an abrogation of foreign policy independence, there are some signs that all may not be lost for middle-power diplomacy of a sort that’s often invoked but less frequently seen. Vietnam really is a remarkable success story and likely to become one of the region’s most consequential rising powers. If ever a partner was worth cultivating, it would seem to fit the bill.

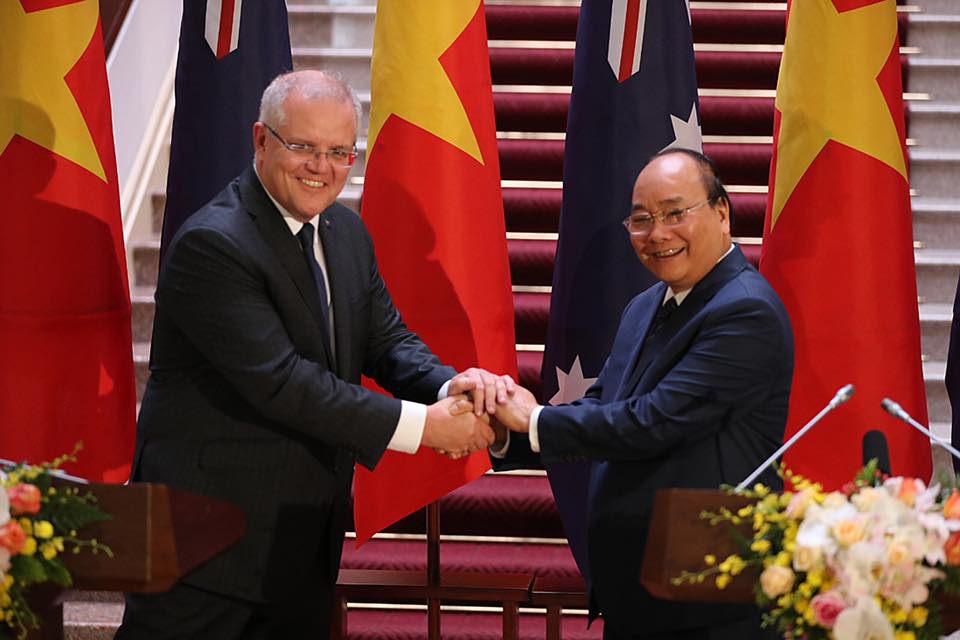

Welcome as Scott Morrison’s visit was in many ways, though, it’s not too cynical to ask whether it would have happened at all were it not for the government’s all-consuming anxiety about the rise of China. It’s striking that in the calculus of threats and opportunities that has shaped Australia’s foreign policy generally and regional relations in particular, it is the former that have been ascendant.

No doubt Canberra’s strategic elites would argue that’s as it should be. Whatever one thinks of the merits of such claims, it’s difficult to see Australia’s dominant strategic culture and values changing, despite the disasters they have led us into over recent years—to say nothing of the pointless loss of life.

But the somewhat unexpected embrace of Vietnam as our new mate really might offer a chance for a little creative diplomacy. True, Australia’s attitude is arguably self-serving and instrumental—Vietnam’s also got an even more immediate and difficult relationship with China—but even inauspicious beginnings can produce good outcomes.

If Australian policymakers are serious about developing an independent brand of middle-power diplomacy, then Vietnam is precisely the sort of country they should be looking to enlist to the cause. As our blossoming friendship suggests, we have potentially common causes in a number of areas, and not just in our unease about China.

As middle powers with little capacity to influence the behaviour of China or the United States when acting alone, we may have more in common with Vietnam than we do with either of the region’s ‘great powers’. Indeed, it’s not too fanciful to suggest that a coalition of like-minded states such as Vietnam, Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, India and Australia might jointly discourage both China and the US from behaving badly.

Of course, that would require Australia to have the capacity to make decisions about what’s in our national interests, rather than reflexively responding to the actions or demands of others. One might have thought or hoped that Australian policymakers would have drawn some instructive lessons about the value of independent policy from our recent involvement in the Middle East, and from what now seems to have been a pointless conflict in Vietnam.

Even more ambitiously, perhaps, it might be possible to develop a foreign policy that isn’t exclusively framed through the prism of potential security threats, especially from our immediate neighbourhood. Morrison’s trip to Vietnam is a hopeful sign. A closer relationship with Vietnam would be one constructive way of honouring the otherwise needless sacrifice of young Australian lives and an indication of how much at least some aspects of regional relations have progressed.