Australia needs to ensure it has the advanced missiles it needs

The pandemic has many lessons for how Australia’s future economy must operate, with opportunities to build new wealth around the global supply chains that originate with us—in natural resources, energy, food, research and education, for example. But these opportunities are accompanied by some nasty risks that the pandemic has revealed with how Australia manages crises—medical and health crises, but also military ones.

And in military crises, a glaring gap we must close is in our ability to supply the Australian Defence Force with precision munitions—notably missiles. Advanced missiles give militaries the edge in combat. In small, discretionary conflicts like Australia’s deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, precision missiles fired from Australian and coalition aircraft were crucial to protecting the lives of ADF personnel, supporting ground operations and killing terrorist leaders and fighters. Without such weapons Islamic State might still control major chunks of territory in Iraq and Syria.

In an actual war, not just difficult counterterror and counterinsurgency operations, advanced missiles are essential to defeat modern military adversaries. Without them, the most capable ships and aircraft are not just defenceless, they are ‘offenceless’ as well—unable to inflict casualties on opposing forces without turning to mass attrition approaches or perhaps nuclear weapons.

But advanced missiles are in short supply, and they’ve run short even in the limited conflicts the ADF has been involved in over the past couple of decades. The ADF gets its missiles from US, European and Israeli manufacturers, at the end of long global supply chains. And, when the home nations of these manufacturers need missiles urgently themselves, their needs can get in the way of meeting ours.

That’s bad, but the situation is actually even worse. Missiles are slow to produce under current industrial structures, so orders have long lead times between placement and filling—think years, not weeks. Manufacturers can surge production for limited periods, but it’s hard for them to sustain a high tempo of production. And missiles require servicing and updating if stored, meaning they might need to be returned to the manufacturers far away.

This was all known before the pandemic, and the Australian military’s approach makes sense in peacetime, and even with missions like Syria and Iraq. But the deteriorating strategic environment in our region, combined with the heightened understanding of how vulnerable extended global supply chains are, means the current situation has become unacceptable. Military conflict beyond the scale of recent deployments is unfortunately quite credible.

Missiles are like a combination of a medical ventilator and the masks health workers need during a pandemic. They’re complex electro-mechanical devices like medical ventilators, so they can’t be made by just anyone (they’re also more complex than ventilators, with bespoke components that aren’t easily replaced by other items you have to hand).

In war, missiles are more like masks in a pandemic than like ventilators, though. You need many thousands of them and they can’t be reused. Ordering or holding a few hundred just doesn’t cut any mustard outside peacetime training routines. So, production is key.

We know with the pandemic that normal supply chains can get disrupted. The level of disruption we’ve seen so far from Covid-19 is nowhere near the level of disruption we’ll see during war.

We also know that even with the limited demands our military has made on existing missile production and ordering systems, we struggle to meet those needs.

The current approach is simply unfit if Australia gets involved in any significant military conflict.

With precision munitions production and sustainment, we must assess what our needs during conflict are likely to be and plan to meet them—instead of planning for peacetime levels of use and supply and hoping things will be all right during war.

Knowledge that our current approach is not fit for purpose requires action. Here, fortunately, things are possible that will greatly reduce our military’s vulnerability to running out of the means to fight.

Australia is fortunate in having close relationships with the countries whose companies manufacture our missiles, and in having subsidiaries of these companies operating in Australia—companies like Raytheon, Rafael, Lockheed Martin and Kongsberg. We also have a workforce that can do advanced manufacturing, with some high-profile examples on display during the pandemic as firms like Gekko systems shifted from mining tech to making medical ventilators.

We haven’t used these companies and government-to-government relationships in a creative way that would close our missile supply gap, though, and we need to do so now.

Now is the right time politically, strategically and economically.

The Australian economy is in the middle of a redesign, with the government starting to focus not just on supporting current employment, but on what will drive future employment and prosperity in the changed world of Covid-19.

The government’s future stimulus program can and should include the defence industry sector—not by spending more on the huge ship, submarine and land vehicle projects, but by investing in the focused area of missile production and sustainment facilities in Australia. This type of manufacture is the iconic high-tech, niche manufacturing area that Australians can excel at and that is feasible given our demographics and capacities.

Incentives, and even co-investment in facilities by the Commonwealth, can help create centres of missile production here which the ADF can rely upon during a conflict. This is about co-production of missiles that are already in or are entering the ADF’s inventory, done in partnership with the companies we buy them from now.

Strategically, it makes sense for other nations—notably allies and partners almost certain to be fighting with us against any common adversary—to be able to be resupplied from Australian missile production centres to supplement their own supply sources, and to add different elements to supply chains that make disruption during times of crisis harder.

Strategically and politically, getting this to happen will involve the highest levels of our political leadership engaging with their counterparts. It’s at least an issue that must be on the agenda of the next annual meeting between our defence and foreign affairs ministers, Linda Reynolds and Marise Payne, and their US counterparts, secretaries Mark Esper and Mike Pompeo.

Getting agreement to and support for high-end US missiles, like the long-range anti-ship missile made by Lockheed Martin, to be manufactured in Australia as well as the continental US through co-production will only happen if the senior leadership of our nations drive it.

Along with our military leadership, they are the ones who can see the strategic value in diversified sources of supply during conflict. We’ll need to put aside hardwired industrial protection mindsets and probably change some longstanding policies on technology release.

But to ensure our men and women who may be fighting future wars in our region have the weaponry to win, in the numbers they need when and where they need it, there’s no alternative to growing Australia’s and its allies’ missile production capabilities. Having these capabilities is also the best way to deter others from engaging in military conflict.

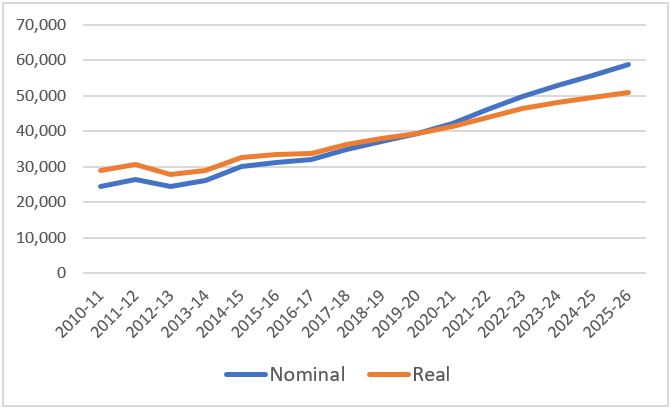

Sources: Department of Defence portfolio budget statements and additional estimates statements. Real baseline is 2019–20.

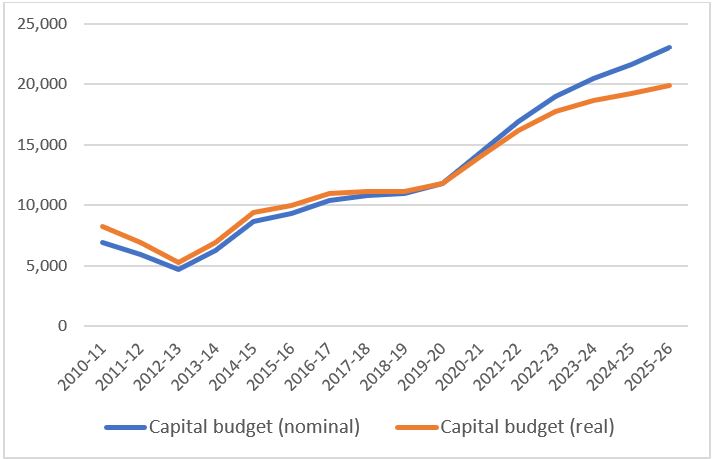

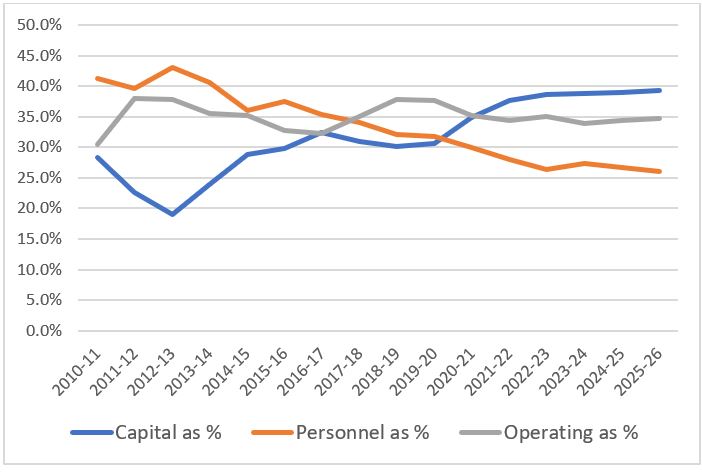

Sources: Department of Defence portfolio budget statements and additional estimates statements. Real baseline is 2019–20. Sources: Department of Defence portfolio budget statements and additional estimates statements; 2016 defence white paper.

Sources: Department of Defence portfolio budget statements and additional estimates statements; 2016 defence white paper.