Deeper Australia–Japan defence ties send strong message to China

One of the strengths in Australia’s relationship with Japan is our shared ability to deliver substance as opposed to verbal bombast unmoored to practical outcomes.

Australia claims to have strategic partnerships with many countries, usually linked to detailed plans for deepening cooperation—but, looking under the bonnet, often the longer the ministerial communiqué, the fewer the results.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s virtual meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida this week will show the opposite is true for Australia and Japan. There is deep substance to the relationship based on a shared strategic outlook and values and a platform of trust built across decades.

On the face of it, the reciprocal access agreement designed to enable closer defence cooperation may seem as if it’s just tidying away practical details of how our forces interact but, to two countries that take the rule of law seriously, these details matter.

With the specifics agreed on how we can access each other’s military facilities, secure port access, landing rights, logistic support, security arrangements and legal regimes, we should expect that there will be an expansion of practical military cooperation.

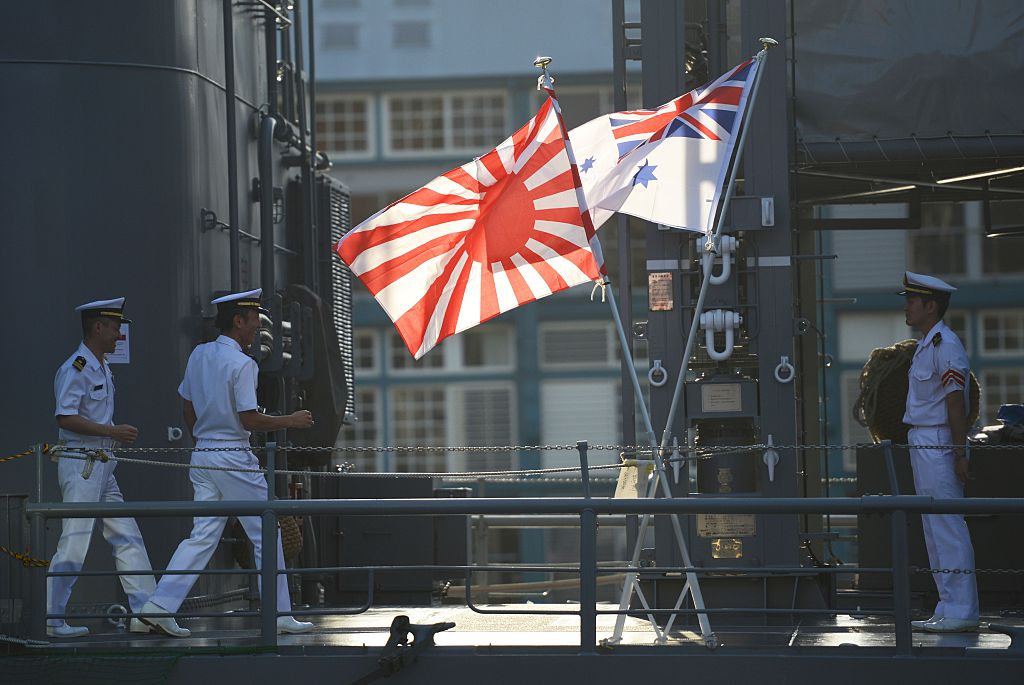

That could mean we’ll see Japan Self-Defense Forces personnel in significant numbers exercising and training with their Australian counterparts and the US marines out of Darwin.

Japanese F-35s could access our training ranges to practise missions over land, Australian submarines and warships could operate out of Japanese military bases, our special forces could build expertise together working with Southeast Asian partners.

This is a powerful expression of how two like-minded democracies can cooperate to shape regional security outcomes. The message to the region is that we have better options than simply trembling and obeying Beijing’s wishes.

Why is this a priority for Japan? First, like Canberra, Tokyo realises we can exercise a stronger influence on regional security by working together rather than separately.

Southeast Asia is a vital strategic zone for both Australia and Japan. China is engaged in a full-on but thus far unsuccessful effort to break ASEAN members away from the world’s democracies and to weaken their regional cooperation. By aligning our diplomatic efforts in Southeast Asia, we strengthen our chances to stop Beijing turning the region into a series of isolated client states.

A second shared Australian and Japanese interest is to make sure we keep the US engaged in the Indo-Pacific. President Joe Biden is clear that Washington wants its allies to step up their own security efforts.

In this case, Australia and Japan are choosing self-help over alliance free riding. The more we can shape an aligned diplomatic and security approach, the more likely it is that the US will stay engaged.

While the aim is to keep the US active in the Indo-Pacific, Australian and Japanese policymakers are alive to the risk that Washington’s isolationist mood might deepen. If that happens, the Australia–Japan relationship becomes the linchpin of security against authoritarianism.

For those critical of deeper Australia–Japan ties (surprisingly, such people exist), the idea of a bilateral pushback against Beijing’s regional domination is simply absurd because nothing can stop Chinese power.

Remarkably, though, the creation of the AUKUS security pact between Australia, Britain and the US, the strengthening of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the emergence of US–Australia–Japan trilateral cooperation, South Korea’s closer engagement with Canberra and the deeper linking of European countries to the Indo-Pacific all show that countries will not bow to Chinese domination.

This is the one unambiguously positive outcome from last year. Through Covid-19 and lockdowns and unrelentingly threatening rhetoric from Beijing, the world’s consequential democracies increasingly are resisting the Chinese Communist Party’s demand that their global leadership come at the price of our subordination.

Could this year be a turning point in Xi Jinping’s political future? He is the architect of the party’s turn to ‘wolf warrior’ aggression, which has done China immense damage globally.

A third Japanese interest in Australia is its need for long-term assured energy supplies. When Shinzo Abe, the Japanese prime minister at the time, visited Darwin in November 2018, media reporting emphasised the symbolic importance of acknowledging the anniversary of the bombing of the city in February 1942, rather obliquely noted in the visit communiqué as ‘the loss and sacrifices of World War II’.

Perhaps just as important to Abe’s visit was ‘the first gas production and LNG shipment from the Inpex-operated Ichthys Project which illustrates the development of bilateral energy cooperation’.

By 2019–20, liquefied natural gas was Australia’s largest export to Japan at just over $19 billion. Coal exports, although planned to reduce across time, were $14.3 billon, while Australian-produced hydrogen remains a future energy possibility. LNG, now accounting for about 40% of Japan’s electricity generation, will remain critical to Japan in coming decades. Australian planners should understand that what is clearly essential to Japan’s energy security is something we need to protect. It escapes no one in Tokyo that the Inpex LNG facility is adjacent to the Port of Darwin, leased for 99 years by Chinese company Landbridge.

The reciprocal access agreement is a treaty-level agreement but doesn’t offer mutual security responses like the ANZUS Treaty of 1951 if either country is threatened. Should Japan be invited to be a formal ANZUS ally? That probably won’t happen soon. It’s unclear that the US Congress and the always unpredictable Japanese Diet would agree on a new formal alliance arrangement.

The ANZUS Treaty does allow the allies (now the US and Australia after New Zealand’s anti-nuclear sidelining from the treaty in the 1980s) ‘to maintain a consultative relationship with states … in the Pacific area in a position to further the purposes of this treaty and to contribute to the security of that area’.

It would be valuable for Canberra and Washington to agree to a formal ANZUS consultative relationship with Japan—meaning, for example, that after the annual Australia–US ministerial consultations, a trilateral Australia–US–Japan meeting would follow.

Japan, Australia and the US are not seeking confrontation with China. Last Saturday, the trade agreement known as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership came into force.

RCEP includes China, Japan and Australia but not the US. The agreement’s 15 members produce about 30% of the world’s GDP. The potential for all countries in the region to benefit from trade cooperation remains enormous, but Beijing’s economic coercion of Australia hardly suggests that China is looking to cooperate.

In the face of such threatening behaviour, Australia and Japan will continue deepening security cooperation, as will others in the region.