Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

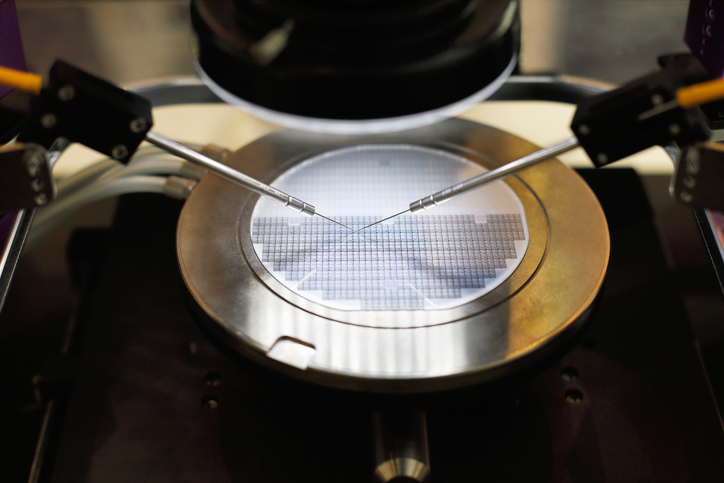

Semiconductors are the single most important technology underpinning leading-edge industries. They’re essential for the proper functioning of everything from smartphones to nuclear submarines and from medical equipment to wireless communications.

Australia’s notable lack of participation in the global semiconductor ecosystem has put it at a geopolitical disadvantage. As a nation, with some niche exceptions, it’s almost entirely dependent on foreign-controlled microchip technology, making it increasingly vulnerable to global supply-chain shortages, shutdowns and disruptions. Such occurrences have become all too common, either because of events such as the Covid-19 pandemic or because of other governments’ attempts to weaponise supply chains for geopolitical reasons.

Having unfettered access to microchips is a matter of economic and national security, and, more generally, of Australia’s day-to-day wellbeing as a nation. In an increasingly digitised world, policymakers must treat semiconductors as a vital public good, almost on par with basic necessities such as food and water supplies and reliable electricity.

By some calculations, Taiwan manufactures 60% of the world’s semiconductors and 90% of the most advanced chips. That alone should focus our minds on how we might shore up our future supplies of this critical resource.

The best solution is for Australia to build its own semiconductor manufacturing capability in selected areas matched to its research and development strengths and key markets. To do otherwise will expose Australia to significant risk, severely constrain our growth as a technological nation and consign us to second-tier status.

Granted, it would be an enormous undertaking—as many well-informed observers including Chief Scientist Cathy Foley have stated. Indeed, we call it a ‘moonshot’ in a report we are releasing today through ASPI.

However, there is a viable pathway that includes pursuing public–private partnerships from an existing R&D foothold, embedding Australian enterprises in friendly and reliable value chains, attracting talent and investment, and leveraging our relationships with strategically aligned and technologically advanced partners. Our report sets out the global context and key elements towards a national semiconductor plan, in which a $1.5 billion government investment through a combination of grants, subsidies and tax offsets could mobilise $5 billion in manufacturing activity.

Other like-minded nations have recognised the urgency and are moving quickly.

The United States and the European Union have both introduced ‘CHIPS’ Acts this year, which deliver subsidies for semiconductor sectors and support for areas that depend on advanced chips, such as 5G wireless, artificial intelligence and quantum science. Japan, South Korea, India and China are all stepping up their efforts. There is a race on, and Australia needs to move decisively.

The fact is, we are no longer in a period of economic liberalism and unrestricted free trade. Rather, nations have found it necessary to adopt the practice of ‘managed trade’ with a pragmatic techno-nationalism. This has been driven by geopolitics, most obviously by China’s mercantilist approach, but also by factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change, which is encouraging shorter supply chains in efforts to decarbonise economies.

Australia has some important strengths: strong institutions, a network of universities and R&D bases, an enterprising business sector, and good friendships with other leading technological nations with whom we share strategic interests, such as the US, the UK, Japan and South Korea. We need to use deft tech diplomacy and get ourselves into global value chains that are made up of reliable, strategically aligned countries—so-called friend-shoring.

Australia already has an important R&D base upon which it can build its new capabilities, in the form of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) network under the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Scheme, which with a modest investment could become more commercially relevant and attract and anchor real commercial foundries.

The ANFF, with eight nodes across Australia, enables researchers to innovate and fabricate advanced products including semiconductors, but not currently at any scale beyond research. Doubling the cumulative investment in the ANFF with a further $400 million in catalyst funding would enable selective key nodes to escalate from one-off R&D to develop pilot production lines geared to volume and yield, closing the gap to producing chips commercially.

They could then create a pipeline of talent and form commercial partnerships. Companies that see this activity are more likely to invest in Australia because they can locate a foundry close to one of these key nodes, rather than build from scratch. Several national and international examples are outlined in our ASPI report.

Significant subsidies and tax concessions would attract semiconductor firms to invest here as part of public–private partnerships. The arrangements set out in the US CHIPS and FABS Acts are a good guide and could be scaled to Australia’s comparative stage of development. Such a commercial foundry partnership would be in the order of a $2 billion investment at a tailored entry point.

The ANFF network already has strength in the research-scale fabrication of compound semiconductors, which use two or more elements and are important in areas such as 5G, photonics and electric vehicles, and we should sensibly start there.

We can then work towards establishing a commercial silicon complementary metal-oxide semiconductor foundry, initially at mature process scale for which there are important markets, and over the longer term, progress to develop leading-edge chips requiring more investment.

We need to ensure that a local talent and innovation pipeline reinforces Australia-based commercial foundries by working with Australian universities and government R&D agencies, and via semiconductor-oriented degree and technical qualifications from universities and technical colleges. We should work with other trusted nations to strengthen this talent pipeline through coordinated research and training among key research universities.

We believe the plan we are putting forward, outlined in detail in the ASPI report, constitutes an implementable blueprint for Australia, not just a pie-in-the-sky idea. Nobody thinks it will be easy, but the strategic imperative is clear.

There are sceptics who will argue we are too small, and that our near-absent commercial chip fabrication capacity means we should concentrate instead on chip design and leave manufacturing to others.

That might be fine in a perfect, rules-based world, but in the real world of supply-chain uncertainty and darkening strategic horizons, we have to address this centre of gravity to avoid being forever a bit player, totally reliant on foreign chips.

Since its announcement a year ago, the AUKUS agreement linking the US and the UK to Australia’s ambition to acquire nuclear-powered submarines has divided opinion.

Critics have portrayed the pact as an alliance that could destabilise the security architecture of the Indo-Pacific region. The notion is that a proliferation of nuclear-powered submarines could invite a regional arms race and leave the door open to the eventual arming of future Australian subs with nuclear weapons.

One year on, are the critics right in their concerns about AUKUS? This question can be answered only by understanding what AUKUS is, and what it is not, and why this agreement matters beyond its immediate technical provisions.

AUKUS is not a security alliance. It holds no provision to suggest such a notion, nor were any of the steps undertaken so far aimed at making it an alliance.

AUKUS is a technology accelerator agreement for the purpose of national defence, no more, no less. It is designed to allow three countries to work closely together to translate the promise of today’s maturing technologies, such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence, into tomorrow’s military edge.

Last April, the three participating governments said that the implementation of AUKUS would be overseen by senior officials and joint steering group meetings that would define different lines of effort.

These areas would be developed through 17 technical working groups. Nine of them are focused on the submarine program, while eight relate to advanced capabilities. This is not an alliance-building policy process, though the sensitive nature of the technologies in question demands a commitment to sharing highly classified information.

This clarification leads to a second observation. AUKUS is not about achieving stability through a form of deterrence delivered by nuclear-armed submarines.

Rather, the themes in the working groups on advanced capabilities suggest that the main aim of the pact is to elevate the intelligence and deterrent value of conventional capabilities.

In this regard, one of the most striking assumptions about AUKUS is the belief in technology as the key to unlocking the full potential of conventional undersea capabilities through enhanced early warning and, if needed, unmatched targeting precision.

Moreover, AUKUS has revealed how leaders in the three national capitals view the maritime domain as a central pillar to the stability of the Indo-Pacific and the wider international order.

This is why understanding what AUKUS is about matters strategically. It matters because it sheds light on a worldview in which the sea is vital to international affairs and, as a consequence, technology that allows for better operation in, and from, this domain has critical value.

AUKUS’s worldview is one that stems from the recognition that the maritime foundations of the international order stand vulnerable to state coercion. Safe and secure shipping lanes and intact undersea cables are engines fuelling economic prosperity and political stability. This is true in the Indo-Pacific as elsewhere.

The recent Russian blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea access and China’s military manoeuvres across the Strait of Taiwan are reminders of the risks of disruption to global prosperity at the hands of states willing to exploit the maritime order to exert political pressure.

AUKUS is, therefore, a down payment to prevent one of the most critical components of the international order from being further destabilised.

AUKUS is a statement about why such a specific technology agreement has wider strategic relevance. It does not destabilise regional security because no other piece in the regional architecture is designed to ensure that the sea remains open to business and unchallenged by revisionist states.

Yet, like any investment in future capabilities, AUKUS is likely to change over time. The sensitive nature of the advanced capabilities explored in the collaboration, from submarines to hypersonic missiles, will invite greater proximity and strategic convergence among the partners. The recent news that Australian submariners will train on British boats implies the understanding of such a demand and the willingness to pursue it.

This is the second reason why AUKUS matters strategically. In a context in which advanced technology will matter increasingly more to maintain a military edge, only trusted partners will be able to achieve the most from defence collaborations.

In AUKUS’s case, renewed conversations about cooperation between Australia and France, and among Japan and the AUKUS partners, indicate that AUKUS is not an exclusive club but one with a membership defined by high standards of innovation and information security.

This doesn’t mean that AUKUS won’t face challenges along the way before Australia deploys nuclear-powered submarines in 2040. Implementing the agreement will put national industrial capacity under pressure. Recent comments from senior American officials suggest that the idea of building the initial submarines for Australia in the US could be problematic.

On the other hand, until the propulsion system is chosen, the design and building of the boats remain an open question. When considered against the impact of technology on future changes in systems and sensors, the division of labour is likely to remain a major changing variable.

What is certain is that one year on, AUKUS has started to chart a clear path as to what it is and why it matters. AUKUS is set on a path about a maritime-informed worldview in which accelerating advanced technology cooperation might very well make the difference in how strategic advantages can be secured and maritime stability can be maintained.

The prospect of the Royal Australian Navy’s promised nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) being built in Australia is firming up, along with a determination that they will be of a design shared with the United States or the United Kingdom and not a uniquely Australian ‘orphan’.

Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles has left no doubt that the government strongly backs the submarine project—including development of the massive industrial base and highly trained workforce required—and the need for Australia to have potent military capabilities.

‘We need a highly capable defence force which has the rest of the world take us seriously and enables us to do all the normal peaceful activities that are so important for our economy,’ Marles said while briefing journalists on the progress of the AUKUS program launched a year ago by Australia, the UK and the US.

A flow of goods was fundamental to an island trading nation, he said, so ensuring freedom of navigation of the seas and of the air above them was central to the economy.

The 300-strong taskforce examining how Australia will acquire its submarines is to make its recommendations to the government in March next year.

That will include what submarine design should be chosen and how these complex boats will be crewed and maintained.

Options include the US Virginia-class and British Astute-class boats. But The Strategist understands that planned new generation of submarines, the American SSN(X) and the British SSN(R), will be considered.

ASPI has released its second update on the AUKUS defence and technology-sharing agreement and makes the case that its focus should be on developing new capabilities that can be acquired rapidly and will significantly boost deterrence. It stresses that need is more pressing even than 12 months ago given the steady deterioration in the strategic environment illustrated by the behaviour of Moscow and Beijing.

It states that while much of the focus has been on the development of SSNs, the other areas of technology cooperation, such as cyber, hypersonics, undersea capabilities, electronic warfare, artificial intelligence and quantum technologies, will be vital in the coming years.

‘Beyond the SSNs, the immediate priority should be long-range strike and deploying critical and emerging technologies to counter Beijing’s own rapidly developing capabilities. Achieving that may require making some difficult choices and trade-offs in the Defence Strategic Review in March,’ the ASPI report says.

It concludes that while innovation and information-sharing as stated areas of technology collaboration sound hackneyed, they are in fact critical for overturning traditional Defence mindsets about research and procurement in order to obtain much-needed capabilities more quickly—an issue that has been identified particularly acutely in Australia.

At his media briefing, Marles said the work of the SSN taskforce task was on track for an announcement early next year and ‘there is a power of work being done to meet that timeframe’.

The optimal pathway was taking shape, Marles said. ‘We can now begin to see it.’

The minister made it clear that Australia is unlikely to end up with a unique SSN design of its own. ‘It’s obviously much better if you are operating a platform which other countries operate as there is a shared experience and a shared industrial base to sustain it.’

And he said all three nations in the partnership are likely to be involved. ‘While the outcome it is yet to be determined, it would be better if we’re in a position where what we’re doing is genuinely a trilateral effort.’

Marles stressed that there was much more to AUKUS and the advanced technology it could produce than submarines. ‘With AUKUS there’s a really huge opportunity beyond submarines of pursuing a greater and more ambitious agenda. This is a large part of what I did in July when I was in the US and subsequently when I was in the UK. We’re very hopeful about the potential that AUKUS represents in respect of that.’

On the issue of how Australia produces the expertise to build, sustain and crew the submarines, Marles said that would involve creating pathways to a workforce with those skills.

‘To that end, it’s really clear that we will have to develop the capacity in Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines. Sovereign capability is part of the story, but so is building up our workforce and industrial base.’

To rely solely on the US and the UK for this work would delay the submarines’ arrival, he said, and he conceded that it would ‘be a while before we get them’.

‘That is why, in terms of getting these submarines sooner, we need to develop our own contribution to an industrial base here at home.’ That would mean the RAN would get its submarines sooner, and it would also provide economic benefits in terms of workforce and productivity.

‘A significant industrial base is going to need to be built here, skills need to be acquired, and so there’s a human dimension to all of that and a workforce which needs to be built up.’

Marles said the goal would be for AUKUS to help develop a genuinely seamless defence industrial base across the US, the UK and Australia.

He said AUKUS would not only deliver SSNs for Australia, but also guide the development of trilateral initiatives where they would have most impact—both for deterrence and operational effectiveness.

‘AUKUS partners are working together to pursue near- and longer-term initiatives that will align our respective priorities and amplify our collective strength, to support a safe and secure Indo-Pacific region.’

In addition to the previously announced AUKUS quantum arrangements and the undersea robotics autonomous systems project, Marles said efforts were focused on artificial intelligence and autonomy, advanced cyber, hypersonics and counter-hypersonics, and electronic warfare. ‘These efforts are being augmented with work on information sharing and innovation to significantly enhance pathways for joint capability development by AUKUS partners.’

Taskforce chief Vice Admiral Jonathan Mead said that in the 12 months since the AUKUS announcement, the resolve of Australia, the UK and the US had strengthened as the strategic environment continued to deteriorate.

‘This is truly a trilateral partnership. We have a shared mission, further confirmed by a very significant delegation here in Australia this week from the UK and US,’ Mead said. ‘We continue our work together towards the decisions that need to be made as part of the optimal pathway for the acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines.’

AUKUS partners were not just focusing on the submarine, he said. ‘Our work to identify the optimal pathway includes many elements that all need to come together to deliver the capability needed to protect Australia and the sea lanes our economy relies so heavily upon.’

Mead said the taskforce was addressing workforce needs from an already strong base because Australia had been operating conventional submarines since the 1960s. ‘Our partners are helping us to understand the discrete skills and workforce numbers required to build, operate, sustain, regulate and safely steward nuclear-powered submarines.’

That will involve developing career pathways for Australia’s submariners that include attendance at UK and US nuclear schools, experience operating UK and US nuclear-powered submarines and secondments in UK and US nuclear agencies.

‘The exchange of these personnel will be both ways and won’t just involve our submariners. Exchanges will also include personnel in headquarters, technical labs, shipyards and sustainment sheds,’ Mead said.

![]()

The $1 billion failure of the Super Seasprite helicopter project was a low point in Australian government procurement. It seems incomprehensible that the Department of Defence could ever replicate it.

In detailing a rapid deterioration in regional security, the 2020 defence strategic update highlights that Australia can’t afford to spend time or money on projects that don’t deliver the required warfighting capability efficiently and effectively. The scope and complexity of the capabilities required for Australia’s security are expanding, while the timeframe for procurement is decreasing. Supply-chain issues are bringing new pressures to design and manufacture more in Australia. Defence must be an effective ‘smart buyer’ as envisaged by the first principles review, which considered it critical that decision-makers assess ‘whether risks and interdependencies have been identified and managed’.

Test and evaluation (T&E) is a key systems engineering tool to identify risk across the capability life cycle, and Defence has long had dedicated policies outlining why it’s important and detailing how it should be used in acquisition, sustainment and force generation.

Following multiple reviews, there have been periodic ‘new’ pathways to establish (or recover) and sustain an effective T&E capability. As the various defence procurement and capability manuals have been updated, a consistent theme has been the vital role of T&E in informing risk-based decisions.

In recommending a smart-buyer approach, the first principles review assumes that Defence can use a T&E process to assess whether risks and interdependencies have been identified and managed. T&E has more recently been recognised as one of the 10 initial sovereign defence industry capability priorities.

Given this consistent emphasis, it should surprise taxpayers that almost every review into defence procurement delivers a negative assessment of how Defence deals with T&E. Concerns include difficulties in defining, creating and sustaining an experienced workforce; the lag and surge of experience on a project-by-project basis that makes it difficult to apply effective T&E early in the capability life cycle; a lack of coordination between the various entities that are stakeholders in defence T&E (including industry); a lack of coordinated investment in T&E infrastructure; and a lack of accountability to ensure that projects engage T&E and take meaningful account of any subsequent reports.

The first principles review highlighted the need to strengthen and place at arm’s length a continuous contestability function that operates throughout the capability development life cycle from concept to disposal.

It transferred accountability for setting and managing requirements to the vice chief of the defence force and the service chiefs within a regime of strong, arm’s-length contestability.

For contestability to be effective, the risk-identification function must be independent so that assessment is made without bias or influence, intended or unintended. Independence also ensures that the assessor of risk has a voice—not a veto—that is heard at each decision-making level of the capability life cycle. Defence and ultimately the National Security Committee of Cabinet should always make the final risk-based decisions as they are responsible for providing military response options to government.

The first principles review recognised that Defence must ensure that committed people with the right skills are in appropriate jobs. Competence is a matrix of qualifications and experience relevant to the task at hand. Those who performed competently as operational commanders or maintenance engineers may not be competent to assess technical performance, integration and certification risk.

Risk assessors working within Defence face various barriers, individual or organisational, that influence whether their voices are actually heard. Risk must be assessed and the results considered by decision-makers. Given the costs and national security implications, the taxpayer deserves to know that this is occurring, despite the commercial and security considerations of full transparency. There’s already a good model for this. The Office of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security conducts regular audits of the national intelligence community as well as specific investigations and reports to the relevant minister and the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security.

Measures to identify and manage risks and interdependencies must be professional and appropriate to needs across the capability life cycle. This is also true for off-the-shelf products that may be used by an ally. In the Australian mission and environment, an allied capability may be the best option to buy, but those operating and managing it, the government and the taxpayer deserve to know that what is being bought may not be capable of everything hoped of it. It could require additional funding, or a supplementary capability may be required for some tasks. This knowledge is important for operational planning, forecasting funding, and even reputation management.

Facing similar issues, the US Congress legislated for independent T&E providing mandatory annual reporting to Congress on all major defence acquisitions. A UK company, Qinetiq, provides technical support to Britain’s Ministry of Defence, including T&E. This model provides independence and highlights that industry can take a lead in determining competence and training requirements, providing training, and managing test ranges and infrastructure.

The defence strategic review should bring a different approach embracing these principles.

It should recommend establishment of a defence capability assurance agency (DCAA), an independent statutory body to assess risks associated with materiel procurement and sustainment, which may include technical risk, systems integration risk, force-integration risk, contractual risk, process risk or even reputational risk. It would be led by a director appointed by a board and its workforce would be qualified and experienced T&E practitioners drawn from defence and industry. The agency would report to the defence minister and parliament.

The DCAA would be required to evaluate risk at agreed points across the capability life cycle and its recommendations would be included in briefs to project managers, assurance bodies, the defence investment committee and the NSC. The agency wouldn’t have a veto but it would ensure that risk-based decisions have a credibly informed basis.

The agency should have a long-term agreement with an Australian industry partner to provide depth of domain expertise and a consistent comprehensive approach to T&E through the life of multiple platforms, environments and systems. The industry partner wouldn’t necessarily conduct all T&E, but as a minimum would oversee the qualifications and professional standards of the workforce conducting T&E.

Defence already has a good model for this approach—the technical airworthiness system. The Defence Aviation Safety Authority (DASA) provides assurance, through assessment of candidate suitability and ongoing audit, that anyone working in this mission-critical and safety-critical area have appropriate qualifications and experience. DASA also provides a range of specialised support services where deep domain expertise is required, such as in aircraft structural integrity.

The industry partner should provide a regulatory function analogous to DASA, in essence acting as the DCAA regulator, and it would be required to sustain an expert workforce providing the capacity to surge, mentor, support and develop T&E practice in support of defence capability. The industry partner could also be responsible for the quality and operation of T&E infrastructure and efficacy of training. Subject to an assessment of probity measures, the industry partner may be limited to selecting, auditing and managing contracted training providers or may also provide a range of in-house T&E training for defence and industry stakeholders.

Scale and flexibility would be achieved by the DCAA drawing on defence personnel or industry providers that meet the qualifications and experience required by the DCAA regulator. This T&E domain expertise would be complemented by the recent operational experience of defence force operators or engineers with relevant T&E training being embedded within DCAA. They could also audit the compliance with qualifications and experience requirements for defence or civilian T&E staff who may be external to the DCAA to comply with operational regulatory requirements.

Defence should be audited to ensure appropriate engagement of the DCAA and transparency of subsequent reporting of identified risks. This should be conducted by a small team with security clearances and subject to protections for commercial-in-confidence information. It would work as part of an independent assurance office.

There are units and individuals within Defence who are professional and competent technical risk assessors, but the organisational inability of Defence to generate, sustain, consistently task and transparently respond to a credible assessment of risk in procurement and sustainment is well known.

The defence strategic review shouldn’t seek to initiate yet another review of T&E within Defence. The strategic imperative for Defence to be a smart buyer, now, should compel the government to instigate legislative reform to establish an independent capability assurance agency.

A key task for those carrying out the government’s defence strategic review is to consider the ability of the Australian Defence Force to engage in a high-intensity, state-on-state conflict in our region. Such a conflict would leave Australia no choice but to fight. It could reset the balance of power and potentially change the strategic alliance framework that has guaranteed Australia’s security for 70 years.

The review is intended to inform the Defence planners who must ensure that the ADF’s posture and force structure is relevant, capable and optimised to meet the range of security challenges facing the nation.

It might be enticing to attempt to predict the precise nature of future conflict but history shows that this is seldom achieved. The only certainty about such a war is that it will be characterised by uncertainty, and that nations are poor at predicting what is required. In February 2011, US Defense Secretary Robert Gates famously told West Point cadets: ‘When it comes to predicting the nature and location of our next military engagements, since Vietnam, our record has been perfect. We have never once gotten it right’. Determining the military capabilities required to succeed in future conflict means understanding what will be needed to resolve a conflict regardless of its character—what will bring victory, and what will lead to defeat.

Much of the recent analysis of the ADF’s force structure requirements focuses on high-end air, maritime and long-range strike capabilities to maximise the advantage afforded by Australia’s geography. These capabilities are essential to deter a potential adversary. Integrated with effects from space and cyber, they will help the ADF hold an enemy at risk from afar and, if necessary, degrade that adversary’s anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) envelope. While essential, these capabilities are incomplete and lack the capacity to compel an adversary to submit. Relying on high-end technologies where adversaries exchange destructive weapons from afar would be no more than attrition warfare by more modern means.

The trap for force structure planners is to be enticed by the concept that future conflict can be won by focusing on technologies that provide the opportunity to empty the battlespace, negating the requirement for forces to manoeuvre so that they can close with and destroy an enemy. History reminds us that to succeed in conflict it’s essential to apply land power to be able to threaten or, if required, destroy an adversary. During the first Gulf War, the overwhelming superiority in stand-off weapons was insufficient to force Iraqi forces to withdraw from Kuwait. It was only when the US-led coalition was able to manoeuvre a ground force to close with and engage in joint land combat that Iraqi forces were evicted from Kuwait. Conversely, the conflicts in Vietnam and Afghanistan demonstrated that superiority in technology and firepower cannot guarantee victory against an enemy that is afforded a haven away from ground combat, where it can regenerate despite aerial bombardment and attacks with stand-off weapons.

Some commentators argue that the lethality of A2/AD capabilities makes the manoeuvre of land forces, especially heavy armoured vehicles, through our region impossible. Critics of armoured land forces also argue these capabilities are no longer relevant due to their vulnerability to advanced anti-armour capabilities and unmanned aerial platforms, as evidenced during the Azerbaijan–Armenia conflict of 2020 and the Russian experience in Ukraine. A detailed analysis of these conflicts reveals that these vulnerabilities result from poor tactical employment and training, and not inherent capability deficiencies.

Conflicts must be seen as evolving campaigns with different mixes of capabilities required at different times. As in the past, future conflict will evolve based on the changing fortunes of the belligerents. Force structure planners must consider the requirements of the ADF through a broad campaigning construct that will evolve over time. The ADF must be able to operate effectively in all domains, adjusting its mix of force as the nature of the campaign evolves. It must maintain and enhance its ability to manoeuvre through the sea, air and land gap to Australia’s north. While this will require continued investment in capabilities to engage adversaries at extended range, conflict has always been, and will always remain, a contest of human will inevitably requiring forces to close and engage in violent and brutal land combat. Accordingly, the ADF will require the capacity to tactically manoeuvre land combat power to close with and destroy the adversary or defend against an adversary’s manoeuvre.

With this understanding, the ADF must continue to invest in land forces. An ADF with ready land combat forces ensures it can meet a key principle of war, flexibility. This will enable it to respond with credible military force to a range of challenges as a military campaign evolves. Given the emerging security environment, now is not the time to limit Australia’s force structure options. Whatever the character of future conflict and however it may unfold, it will only be resolved by people. To compel an adversary into submission, the ADF must develop the capacity to manoeuvre a truly integrated joint force, including lethal, protected, mobile and connected land forces, capable of fighting aggressively and winning conclusively in joint land combat.

Which country is Australia’s most important defence partner in Southeast Asia? I’m guessing not many readers of The Strategist would put the Philippines at the top of their lists. The correct answer, of course, is, ‘It depends.’ Yet, for some of the most demanding military scenarios that may confront the Australian Defence Force in the decade ahead, such as a war over Taiwan or in the South China Sea, the Philippines could be an indispensable partner because of its location and potential willingness, as a fellow treaty ally of the United States, to grant access and logistical support to Australian forces. Although low profile, the Australia–Philippines defence relationship has surprising depth and potential, meriting a closer look.

Australia’s deepest defence ties in Southeast Asia are with Malaysia and Singapore, through the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) and as bilateral partners in their own right. Singapore’s military capabilities are the most advanced in Southeast Asia. But the utility of the FPDA in a South China Sea contingency is questionable because its remit is limited to West Malaysia and Singapore. The probability of these countries extending basing access to Australian forces for operations to defend Taiwan is almost certainly lower.

Australia’s defence relationship with Indonesia attracts a political premium for Canberra, but it lacks strategic underpinnings and Jakarta is unlikely to offer access for the ADF beyond transit through the archipelago. Vietnam holds out more promise of a like-minded approach to pushing back against China’s expansionism in the South China Sea. But Hanoi keeps its distance from the US and its allies in the military domain. Australia has expanded its defence relationship with Brunei since 2020, but like most Southeast Asian countries the small sultanate would tread very carefully in any crisis or conflict involving China unless it is directly threatened.

The US is likely to confront similar ambivalence across Southeast Asia, including from its ally Thailand. Laos and Myanmar would remain neutral, at best, while Cambodia is in an invidious position as the prospective host for Chinese naval and possibly air force assets.

The Philippines has been portrayed as an unreliable ally of the US, with some justification. The 2014 Philippines–US Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement failed to progress significantly under Rodrigo Duterte’s dyspeptic presidency. The vital visiting forces agreement was nearly terminated. But alliance relations have stabilised since 2020. Beijing’s relentless pressure tactics in what Filipinos call the West Philippine Sea have darkened perceptions of China in the Philippines. The government under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, though still new and by no means anti-China, appears to recognise the irreplaceable value of the US alliance for deterring further aggression by China, despite Washington’s mixed record of deterrence in the South China Sea.

In Philippine military circles there’s a sense of realism that proximity to Taiwan would make it extremely difficult for Manila to stay on the sidelines during a major conflict there. In the worst case, China could occupy Philippine islands in the Bashi Channel or even parts of northern Luzon, to deny the use of adjacent territory to the US or its use as a safe haven for Taiwan’s armed forces. Fighting could spread to the South China Sea proper, including China’s artificial island bases, one of which—Mischief Reef—sits within the Philippine exclusive economic zone.

The fraught prospect of a high-intensity maritime conflict between China and the US shines an uncommonly intense light on defence ties between Canberra and Manila. Fortunately, Australia and the Philippines, which have been comprehensive strategic partners since 2015, have already established a notably broad-based and durable bilateral defence relationship. It has deeper historical roots than widely assumed. In World War II, Australian forces made an active contribution to the liberation of the Philippines, incurring significant losses at Lingayen Gulf. The newly independent Philippines and Australia fought side by side in the Korean War.

In more recent times, the basis for cooperative defence activities was a bilateral memorandum of understanding agreed in 1995. That opened the door for members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to receive education and training in Australia. Around 100 AFP, coastguard and civilian defence personnel do so every year. ADF mobile training teams also deliver courses in the Philippines. Terrorism was the main focus of security cooperation with the Philippines for almost two decades after the 11 September 2001 attacks on the US. The culmination of that effort was Operation Augury—Philippines, which provided training to more than 10,000 AFP personnel during and after the siege of Marawi city, from October 2017 until December 2019, when the operation transitioned to become the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Program. Since then, the emphasis has shifted towards assisting the AFP’s modernisation and external defence plans.

Defence capacity-building delivered to the Philippines has focused on maritime security and domain awareness, as well as the lingering threat from terrorism and pandemic healthcare more recently. In July 2015, Australia donated two landing craft to the Philippine Navy. A further three were acquired in March 2016.

Australia is the only country apart from the US with which the Philippines has a reciprocal visiting forces agreement, signed in 2007. It entered into force in September 2012, fortuitously facilitating the ADF’s delivery of disaster relief assistance to the Philippines in the wake of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013. In August 2021, the two governments concluded a mutual logistics support arrangement, providing a second pillar to sustain the deployment of ADF assets and personnel to the Philippines. It would be too crude to suggest that Australia provides capacity to the AFP and receives access for the ADF in return, though that does provide a basis for reciprocity in the defence relationship. Underpinning the relationship at a human level are close interpersonal connections across the armed services and defence bureaucracies.

Like most militaries in Southeast Asia, the AFP is army dominated, despite the Philippines’ archipelagic geography, but there are also bilateral links between the Australian and Philippine navies and air forces. The Anzac-class frigate HMAS Arunta and corvette BRP Apolinario Mabini exercised together in the Celebes Sea in September 2020, and Australian navy patrol boats have previously been deployed to the Philippines. The Philippine Air Force is currently participating in Exercise Pitch Black in northern Australia. Earlier this year, the Royal Australian Air Force delivered a combat air control simulator to the Philippine Air Force ‘to support training’. Since at least 2017, the RAAF has periodically conducted surveillance flights over the South China Sea from the Philippines.

In May, one of a pair of RAAF P-8A Poseidon aircraft operating from Clark Air Base, north of Manila, was unsafely intercepted by a Chinese J-16 fighter reportedly near the Paracel Islands. Australia’s ability to fly P-8A missions out of the Philippines demonstrates the strategic potential of the relationship. One obvious deficiency in defence relations is the absence of an industrial-level partnership. The recent failure of Australian shipbuilder Austal’s bid to supply six new offshore patrol vessels to the Philippine Navy was a missed opportunity in this regard.

One reason Australia’s defence profile in the Philippines doesn’t receive more attention is because the US alliance still tends to overshadow Manila’s defence policymaking. Australia’s defence offer to the Philippines is on a modest scale compared with US programs. Nonetheless, Australia benefits from operating in a complementary fashion without the political drag that sometimes attaches to US activities in the Philippines because of historical baggage.

US military exercises with the AFP provide opportunities for the ADF to train alongside Americans and Filipinos. In the 2022 iteration of Balikatan, for example, Australian commandos took part in a helicopter raid on the island of Corregidor together with US and Philippine marines. However, Australia’s population is around a quarter of that of the Philippines and there are just 60,000 ADF personnel in uniform. Canberra therefore needs to manage Manila’s expectations of what Australia can realistically deliver, short of a formal alliance.

Australia’s defence partnership with the Philippines is repaying the dividend of past investments at a time when the limits to more traditional relationships in Southeast Asia are becoming increasingly apparent.

Australia’s parliament has little chance to place legal limits on the profound prerogative of the prime minister and the executive to take the country to war.

Instead of pushing against the constitution, look to build new conventions into the Australian way to war. Seek to ‘parliamentarise’ the war powers.

Aim for a checklist if not a legal check when war is launched. And use the checklist for greater parliamentary oversight of the way war is waged.

Stronger conventions in the House of Representatives can offer more detailed benchmarks at the threshold moment when the prime minister and cabinet mobilise the Australian Defence Force. Benchmarks can then be used by both houses of parliament, especially the Senate, to monitor and review the course of military action.

Over the past two decades, prime ministers as diverse as John Howard, Tony Abbott and Julia Gillard have offered footholds on which parliament could build conventions.

To use those footholds, parliament must edge closer to the strategic and diplomatic space dominated by the prime minister and cabinet.

What’s needed is more ‘creative tension’ between the executive and parliament, the phrase used by former Liberal senator and international relations scholar Russell Trood and ASPI’s Anthony Bergin in their 2015 paper. It was also at the conceptual heart of the Senate lecture on parliament and national security Bergin delivered in 2017 after Trood’s death.

To get closer to the profound prerogative, parliament has to build more day-to-day muscle. Move the needle in the direction of change, Trood and Bergin argued, to:

Trood and Bergin argued that parliament has never thoroughly examined how to extend its authority over the overseas deployment of the ADF. They were cautious, though, about the idea that parliament should be responsible for declaring war, doubting that it’d improve the way Australia makes policy:

Governments are elected to govern, and that authority extends to making difficult decisions about the appropriate use of military force. Other salient factors are the need for timeliness in decision-making, the unique knowledge that governments possess about often complex foreign affairs issues and the challenges in securing an appropriate resolution from a possibly fractious legislature.

Rather than a futile frontal attack on executive prerogative, dial up what parliament can rightfully expect—and properly do.

Existing precedents and habits can be made conventions in the House of Representatives. Strengthened habits in the Senate could feed the powers of review it already holds (and inform the way it grills defence leadership in regular estimates hearings).

In the House of Representatives, use the existing prime ministerial footholds. Build on the ANZUS precedent set by Howard with his parliamentary resolution after the September 11 attacks on the US; Howard’s Iraq war resolution; Abbott’s criteria as the basis for future resolutions on war; and the Afghanistan conventions established by Gillard.

The ANZUS precedent is the eight-point motion that Howard moved in the House on 17 September 2001, invoking the ANZUS Treaty following the 9/11 attacks on the US.

The motion didn’t go to the military actions that followed, but set out fundamental arguments for why Australia would act. That’s the place to start for all future motions on military action.

A resolution for war should be considered by the House even if—as happened with Iraq—the government has already sent Australia’s military to fight. Australian troops were in action in Iraq on 20 March 2003, when the House voted to approve the Iraq motion moved by Howard (and defeat Labor’s rival motion). Howard’s resolution was a damnation of Iraq as a rogue state and an assertion that Australia was acting under clear authority of the United Nations. Labor’s opposition motion argued that Australia didn’t have UN authority to commit troops.

Viewed today, the two resolutions frame Australia’s Iraq argument—and failure.

In the debate on the Iraq resolution, Howard said Australia’s forces would be part of the US-led coalition but operate under separate national command with separate rules of engagement and separate targeting policies.

After the war, in ‘the post-conflict stage, the phase 4 stage,’ Howard said, there could be a role for parliament’s ‘Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade in relation to oversighting the Australian involvement in the phase 4 process’. The committee never played such a detailed role in Australia’s Iraq experience, but the ‘oversight’ thought is a parliamentary foothold for all stages of future wars.

The ANZUS and Iraq resolutions are starting points for future war resolutions that seek more detail about war aims. The House should seek a motion that offers answers to the fundamental questions posed by Abbott on 1 September 2014.

In a statement to parliament on the threat that ‘the death cult’ Islamic State posed to Iraq and Syria, Abbott said that if a request for Australian military help in Iraq came from the US and the Iraqi government, it’d be considered against these criteria:

Is there a clear and achievable overall objective? Is there a clear and proportionate role for Australian forces? Have all the risks been properly assessed? And is there an overall humanitarian objective in accordance with Australia’s national interests?

For a war against another nation, rather than terrorists, other big questions could be added to the Abbott criteria: What should the scope of the commitment be and what are the aims? What forces are needed? What would victory would look like, or what is the desired end? What should the exit strategy be?

The resolution that goes to the House, even if the government has already ordered war, should address those fundamental issues—of aims, means and ends. The executive has the power to give the order, but it isn’t asking too much that it give parliament and the people a clear account of what’s to be done.

If those precedents become conventions, we would see a House of Representatives resolution on committing Australian forces overseas that sets out the objectives and conditions of the deployment. That resolution should declare the mission, the aims (Abbott’s clear and achievable objectives), the forces that could be used, and the end point and anticipated exit strategy.

The initial resolution and all the regular government statements that must follow should draw on Gillard’s Afghanistan speech on 19 October 2010. She told parliament that she would ‘answer five questions Australians are asking about the war’:

– why Australia is involved in Afghanistan;

– what the international community is seeking to achieve and how;

– what Australia’s contribution is to this international effort—our mission;

– what progress is being made; and

– what the future is of our commitment in Afghanistan.

A significant Gillard marker was her promise of regular formal statements to parliament: ‘[T]oday I announce as Prime Minister that I will make a statement like this one to the House each year that our Afghanistan involvement continues. This will be in addition to the continuing ministerial statements by the Minister for Defence in each session of the parliament.’

Using those benchmarks, there should be a standing reference to the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence whenever Australian forces are deployed. At the least, the committee should hold hearings once a year in which it calls the secretary of defence and the chief of the defence force to give evidence on the deployment or conflict and to testify how the terms of the mission resolution are being met.

With such a framework in place, the regular Senate estimates hearings could become the venue to review progress against the stated aims. Parliament would be doing some of the heavy lifting on behalf of the people.

In building stronger conventions on war, parliament should be guided by the final words of Peter Edwards’s official history of the Vietnam War.

In committing to future wars, Edwards wrote, Australians should hope ‘both the government of the day and any who opposed it might display greater political maturity, social responsibility and diplomatic awareness than did some of their predecessors between 1965 and 1975’.

That sounds like a job for the House and Senate. Build parliamentary habits to hold the hubris and help Australia understand its way to war.

Missed by many amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, Australia’s federal election and China’s inroads into the Pacific was the European Union’s strategic compass, launched in March after almost two years of development. As Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles announces a visit to France, we should understand its importance—and its significance for Australia—and encourage its implementation.

Much happened in the past two years, including Covid-19, a deterioration in EU–China relations and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In this context, the strategic compass is a potential game-changer or, in the words of EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell, a ‘turning point’. It’s the first time the 27 EU members have come together to focus on defence and security rather than just trade. France considers it a significant achievement of its role as chair of the EU Council.

The strategic compass, which the EU Council describes as ‘an ambitious plan of action for strengthening the EU’s security and defence policy by 2030’, launched in a ‘more hostile security environment’. It is aimed not only at empowering the bloc’s strategic autonomy, but also at fostering its cooperation with security partners. It coincides with NATO’s launch of its 2022 strategic concept, which in an unprecedented way refers to China as a challenge.

This shift in Europe comes at a time when Australia is resetting its relations with France following the cancellation of the Attack-class submarine project and with the EU after years of misalignment on climate policy. Australia’s national security and regional stability require both resets to happen, so the government should embrace the compass as an opportunity to proactively encourage the EU’s strategic shift, notwithstanding its focus on Russia.

The EU has for many years approached its relationship with China hoping an engagement strategy that was relatively silent on malicious activity would result in both EU economic prosperity and increased liberalisation in China. The result has been some economic prosperity but more dependence and interference, with greater opportunities for attempted coercion by Beijing.

While the EU’s 2021 Indo-Pacific strategy referred to China as a systemic rival, it also called it a partner. This is true for almost all countries by virtue of China’s trading relationships, but the inconsistency and ambiguity were always a short-term tactic rather than a long-term strategy.

The strategic compass needs to be that long-term security strategy. A lasting problem is that some EU members view the US with cynicism. The clear emphasis of the compass on EU security autonomy is in part born out of an aim to quell limited but loud public discontent about the union being too reliant on the US. Ensuring the US is held accountable for its actions is vital, but EU members’ hesitancy to consistently hold Beijing to the same standards has hurt Australia, because it feeds into regional fears of Beijing’s coercive power and reinforces a false narrative that strategic competition is limited to the US and China.

On the other hand, EU countries collectively have more influence and trust than they may realise in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Australia should work with the EU to turn this position of trust into a position of positive influence. The strategic compass must be part of this, with Australia able to emphasise the strategy’s focus on strengthening security partnerships with both the EU and individual member states. This is vital for foreign and defence policy, to ensure EU members know that groups like AUKUS and the Quad don’t rule out broader security partnerships.

The EU’s experience with China should be a key lesson for our region, which would benefit from EU members being upfront about the challenges they have faced. The Chinese government has tried to use its economic heft to bully and coerce individual EU members like Lithuania and the union as a whole. By itself, the Baltic country would not have stood a chance, but the EU showed its collective strength and how to counter coercion from a major power. This is something that single member states too often forget.

The response required EU members to be willing to forgo short-term economic gain and impose costs—both reputational and economic—on Beijing, a combination that has in the past often proven to be an insurmountable obstacle for collective action. It stymied China’s attempt to embed itself in Europe through the 17+1 trade grouping and other initiatives—thinking it could rely on those in Europe who thought the easiest way out of economic crisis was through Beijing’s largesse. The 17+1, now effectively 14+1 after Lithuania and, more recently, Estonia and Latvia left, is on the verge of collapsing because of China’s malicious activities, in particular economic coercion and failure to deliver promised results.

While the EU–China relationship shouldn’t have become as entangled as it did, the Lithuania case was the catalyst for refocusing on individual and regional sovereignty. The EU has finally found some momentum to look after its unity and integrity.

Why does this matter to Australia? Apart from the principle of supporting all partners subject to coercion, the similarities with the Pacific are clear—China is picking off those small nations keen on quick financial support and making inroads through what it sees as weak links.

Hoping, or even expecting, a Lithuania-style own goal from Beijing in the Pacific is not a strategy. Australia now has a chance to become the leading partner for the EU in the region, especially with its renewed focus on climate policy that matches the Pacific’s top priority, as well as the EU’s. Combine that with Australia’s efforts to reset with France and expect to see a Pacific program as part of reinvigorated relations.

Active Australia–EU collaboration, along with partners such as the US and Japan, can ensure we are not just relying on China’s own goals but scoring plenty of our own.

According to media reporting, the Australian defence company DefendTex will provide Ukraine with 300 of its Drone40 small uncrewed aerial vehicles. The specification sheet for the D40 says it has a range of 20 kilometres and a maximum flight time of 30 to 60 minutes. The D40 has a variant that carries a 40-millimetre grenade and functions as a loitering munition, or ‘kamikaze drone’ in common parlance, but it’s also capable of carrying other payloads such as sensors and electronic warfare options. Its small size means it can be easily carried by dismounted soldiers and can be launched either from a 40-millimetre grenade launcher or simply thrown into the air.

Coming on top of the most recent announcements of further high-tech US military aid, it’s good news for Ukraine. It’s increasingly clear that the war there is a struggle between 20th-century industrial-age warfare and 21st-century digital- and information-age warfare, with Ukraine’s supporters in liberal democracies providing it with the systems needed to successfully conduct the latter. While Russia’s industrial-age model may initially have had the advantage, that was largely due to the legacy of years of industrial production of weapons and munitions, which are now being rapidly consumed on the battlefield. But the technological pendulum is increasingly swinging in Ukraine’s favour in ways that Russia can’t hope to match, particularly while it is suffering from sanctions on high-tech components such as computer chips.

The export success is also good news for DefendTex, an Australian-owned company with a history of innovation in the defence and security sector. But the sale does raise some issues. The first is, when will the Australian Department of Defence acquire the D40 in commercial quantities? The system, developed with funding support from the Defence Innovation Hub, is now mature. It’s been acquired by the British Army and trialled by the US Marine Corps. In fact, after trialling it, British soldiers insisted on taking it with them on their deployment to Mali.

We’ve seen a proliferation of small drones in the war in Ukraine, both military and commercial. Any conflict Australian troops deploy to will be no different. But do we really want to see Australian troops having to improvise solutions on the battlefield—as the Ukrainians have been forced to do, such as by using 3D printers to attach legacy mortar rounds to small consumer drones and turn them into mini-bombers—when Australian industry already has the ability to provide them with world-leading equipment?

Defence’s innovation programs are a microcosm of the broader Australian research and development effort—we create innovative products but can’t seem to commercialise them at home. The D40’s development was funded by Defence grants—but one has to ask why Defence is funding innovative technologies if it’s not going to acquire them once they’re demonstrated to work. It’s a common refrain from Australian small and medium-sized enterprises. In other countries, sales to the local defence force spur exports; here, Defence often won’t buy local products until they’ve been sold overseas, and even then it’s no sure thing.

The bigger issue is what this sale tells us about Australia’s industrial capability. Australian industry can develop precise, lethal capabilities, and it can do it fast. And it doesn’t need overseas intellectual property to do it.

This is relevant in the context of the sovereign guided weapons enterprise announced by the previous government to provide secure supply chains for the munitions that are essential for modern warfighting. But so far, there seem to be two answers to the question of how we make anti-tank missiles here. The first, based on the experience of the Israeli Spike missile, is we don’t. Four years after the government announced Spike missiles would be built in Australia, Defence still hasn’t started, apparently due to certification issues.

The second answer, based on the trajectory of the sovereign guided weapons enterprise over the past two years, is to establish some kind of partnership with a large US prime contractor, then spend years negotiating around the strictures of the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations, overcoming Congress’s qualms about outsourcing US jobs, setting up a production line, sourcing hundreds of components from supply chains around the world and finally, at some point down the track, producing a missile.

However, if we turn the question around and ask how we can quickly develop ways to destroy armoured vehicles, we don’t have to default to the answer being ‘Build anti-tank missiles.’ If we leverage the innovation and technologies of the commercial sector it can be done quickly. In short, it’s a lot easier to precisely move high explosives from one point to another 10 kilometres away using existing commercial technologies such as small rotary-wing motors than it is to design and build rocket motors and put missiles around them. DefendTex has demonstrated that, but there are other small Australian companies that have adopted that approach to deliver the ‘small, the smart and the many’ in the form of cheap but precise loitering munitions.

By all means, let’s build US missiles here, but we also need to pursue other lines effort as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, if we have to wait for Defence to certify everything using its existing processes and standards, it seems we’ll be waiting a long time for capability. Of course, the Ukrainians don’t seem to be too concerned about certification of the weapons they’re pressing into service.

The basic fact is that Defence is an artificially protected monopoly. Monopolies simply can’t innovate rapidly. The reason our electricity sector has managed to move down the path of renewables as far as it has despite the stonewalling of the previous federal government and the incumbent major players is that many other players have gained entry, creating competition and driving innovation. There are ways in which Defence should enjoy a natural monopoly; we don’t advocate for mercenaries. But when Defence is both a monopoly provider of security services to the government and a monopsony consumer of security goods and services from industry, it is a recipe for stagnation. Sometimes Defence needs firm external direction—it’s the role of the new government and the defence strategic review to provide that.

Developing Australian companies’ ability to produce small guided weapons at scale won’t just benefit our defence force. We’ve recently seen the prospects for conflict over Taiwan intensify, provoking greater debate in Australia about what we would do if Beijing ordered an assault. Providing Taiwan with tens of thousands of small kamikaze drones that can sinking landing craft and destroy armoured vehicles will make a tangible difference to its prospects of resisting invasion—perhaps even more of a difference than sending a small number of high-value Australian Defence Force assets and their crews.

By leveraging the benefits of Industry 4.0, Australia can become a key part of the arsenal of democracy.

The way Australia goes to war needs new conventions to give parliament a greater role in the weightiest choice any nation can make.

Creating parliamentary customs or conventions is the only realistic way to touch the prime minister’s almost unfettered power to launch war.

The parties of government—Labor and Liberal—will not give parliament any legal hold over the prime minister’s profound prerogative for war. Convention will have to be created, instead. Much history—both military and political—informs this understanding.

Since federation, war has been a defining element of Australia’s identity and the way we approach the world. In a span of nearly 90 years—from 1914 to 2003—Australia chose to go to war nine times.

The political truth is that prime ministers and governments—creatures of the House of Representatives—are usually fighting the Senate, where the government of the day seldom commands a clear majority. The parties of government will not give the Senate any more power, especially over the war powers.

The Senate experience means that politics pushes against the logic of putting into law the proposal in 2010 from a former Australian Army chief, Peter Leahy, that a resolution of each house of parliament should authorise overseas service. Leahy’s recommendation for parliamentary ratification for military deployments reads:

Both Houses of Parliament should be required to authorise by resolution any decision to commit the Australian Defence Force to warlike operations or potential hostilities within sixty days of the decision to commit forces. Given that the contemporary kinds of conflict tend to run for many years, ADF deployments should then be reconsidered by the Parliament on an annual basis.

A resolution of parliament within 60 days of war or deployment draws on a similar period in the US War Powers Act. Skip by the question of how much the US Congress has checked the president’s war powers to consider Leahy’s equally important call for clear public statements of national interests and strategy. Here his wording shifts from parliamentary resolution to government statement:

For each military deployment, the Australian Government should provide and routinely update a clear statement of national interests and strategy. The strategy statement should include the elements of power to be used, the end state to be achieved, an indication of the exit strategy and likely time frame for the commitment of force.

The many parallels between Australia’s entry into the Vietnam and Iraq wars offer the history for seeking benchmarks the parliament can apply to the executive’s profound prerogative. If not aspiring to legal checks, let’s at least have a good checklist.

Former Australian ambassador Garry Woodard’s examination of how the prerogative worked in deciding to commit in Vietnam and Iraq showed ‘the dominance of the Prime Minister, decisions made in secret by a small group of ministers obedient to him, minds closed against area expertise, preference for party political advantage over bipartisanship, and willing subservience to and some credulity about an ally, the United States’.

As usual, Woodard shows his deep understanding of the Canberra system. The caution also offered by history, though, is that greater parliamentary involvement would not have stopped Australia going to Vietnam, Afghanistan or Iraq. Parliament can give greater transparency about Australia’s march to war and set benchmarks for judging the course of war. But parliament might not curb the war habit.

Wedging Labor on the Vietnam commitment in 1965, the Coalition government rode initial voter enthusiasm for the war to increase its majority in the 1966 election, arguing that Labor’s opposition to Vietnam showed it was weak on the US alliance. Both sides of Australian politics supported the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and any greater parliamentary involvement would have been an expression of that unanimity.

Iraq divided the parliament just as it split Australia from the very start. John Howard used his prerogative as prime minister with the precision of a master politician. He held his cabinet and party together (Labor was again wedged), and Australia joined the Iraq invasion—lots of alliance loyalty but few smarts in committing early with few questions.

The idea of more smarts and more questions is where a bigger role for parliament comes in.

Australian researcher Peter Mulherin pursues this in ‘War-power reform in Australia: (re)considering the options’, arguing for a new war-powers convention as a small step towards democratising the decision of going to war: ‘While not legally binding, this constitutional convention would represent an agreement by the major parties that overseas combat operations will be properly debated in Parliament.’

Beef up the informal rules that guide the parliament so it can impose informal constraints on the executive’s power. Express what parliament and the people are owed, perhaps codified in a non-binding resolution. Strengthening parliamentary convention would be an improvement on the status quo, Mulherin concludes:

Despite some arguing that legislative reform is preferable, it may also be impossible, given the reluctance of the Coalition and ALP to change the law. Therefore, a new constitutional convention would be an important step towards strengthening debate when Australia goes to war.

In ‘Going to war democratically: lessons for Australia from Canada and the UK’, Mulherin argues that Canada and the UK have taken steps this century to ‘parliamentarise’ their war powers, while in Australia the prerogative remains absolute.

Citing Canada and the UK as comparable parliamentary democracies with close alliance and historical ties, Mulherin lays out a three-step argument about what Canberra can learn from London and Ottawa: ‘(1) a more democratic foreign policy formation is a normative “good”; (2) war-power reform is one way to democratise foreign policy formation; and (3) lessons drawn from the examples of Canada and the United Kingdom may help Australia reform its war-power arrangements’.

So, no law, but stronger conventions in the House of Representatives offering more detailed benchmarks for the powers of review held by the Senate.

Over the past two decades, prime ministers as diverse as Howard, Tony Abbott and Julia Gillard have offered small footholds on which parliament could build. My next column will draw wordage from those footholds to do some convention drafting.