From Whitlam to Albanese: portents and echoes

A new Labor government takes office, threatened by a global recession, seeking a new start with China, and worried by war in a ‘time of entrenched geopolitical competition and stark divisions’.

A tough menu confronted Gough Whitlam’s government when it won office on 2 December 1972—leaving the Vietnam War as it swiftly exchanged diplomatic recognition with Beijing.

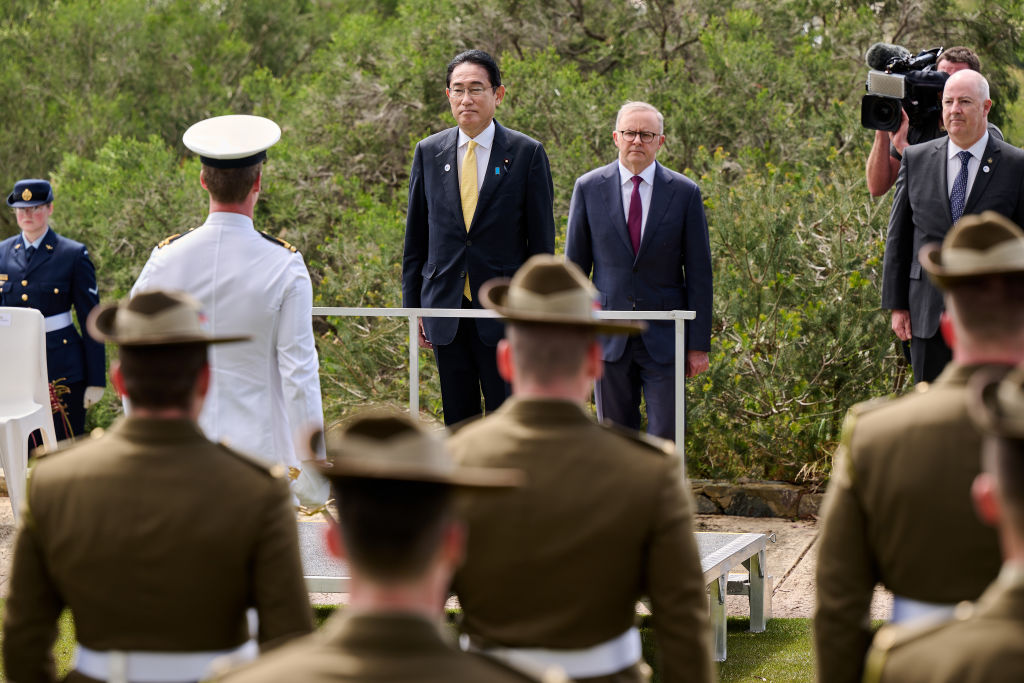

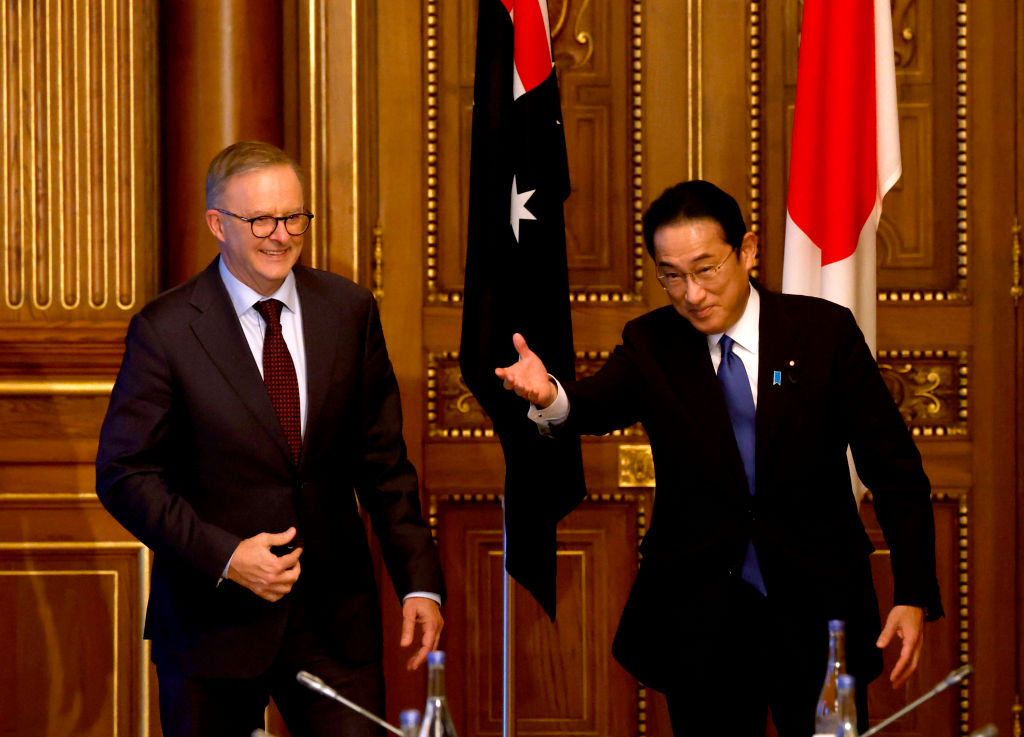

The 50th anniversary of the Whitlam victory on Friday offers echoes and portents for Anthony Albanese’s government, which last week marked six months in office.

For the first time since Whitlam, Australia’s defence minister is also the deputy prime minister. Indeed, the ministries held by Albanese’s leadership group make it the most internationally focused cohort at the top of an Australian government in 50 years. Labor’s Senate leader is the foreign minister, while the Senate deputy leader is the trade minister. The Coalition has a similar international orientation—opposition leader Peter Dutton is the former defence minister, while the opposition leader in the Senate is the shadow foreign minister.

The leadership line-ups speak of another time of geopolitical competition and stark divisions.

Albanese has been overseas in five of the six months he’s been prime minister. The much-travelled Whitlam would have saluted; ‘Comrade,’ he lamented ironically in 1974, the UN is creating countries ‘faster than I can visit them’.

The China story joins the two governments. Foreign Minister Penny Wong made the comparisons in delivering the 2022 Whitlam Oration and in her speech about the 50th anniversary of Australia–China diplomatic relations.

Whitlam’s embrace of China was supremely optimistic. Wong offers a cautious step-by-step prescription to ‘stabilise’ the relationship: ‘What we want to do is to continue to engage, cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, engage in the national interest, and I think what’s important is we can grow our bilateral relationship alongside upholding our national interests if both countries navigate our differences wisely.’

The Albanese government’s key talking point has moved from the three-word bumper sticker describing the problem (‘China has changed’) to the one-word prescription, ‘stabilise’.

In defence, the Albanese government pushes to make Australia’s military fit for purpose, fitted with kit to meet the purposes we’re likely to face in ‘a less safe and less stable world’.

The defence strategic review, due to report in March, faces big tasks, but it’s an echo in the minor key of defence’s ‘massive upheaval’ under Whitlam. Five departments (Defence, Army, Navy, Air and Supply) were merged into one; three services were brought into one Australian Defence Force; and the ‘diarchy’ was born, making the defence secretary and the ADF chief jointly responsible to the minister.

Whitlam delivered Australia strategic benefits that are still central today. He held on to the US alliance even as he battled Washington. He helped give birth to an understanding that Australia could defend itself, while proclaiming that Australia should find security in Asia, not seek security from Asia.

The Albanese government has embraced the alliance, while Whitlam’s alliance commitment was defined by the right to disagree (the US alliance wasn’t the ‘be all and end all’ of Australian foreign policy, Gough quipped). Whitlam’s differences with Richard Nixon’s administration are recorded in James Curran’s Unholy fury: Whitlam and Nixon at war; Curran says it was the closest the alliance has come to destruction.

Whitlam’s focus on Southeast Asia meant Australia became ASEAN’s first dialogue partner. But Whitlam’s effort in his first days in office to create an Asia–Pacific forum was quickly killed off by Indonesia—an early demonstration of the veto ASEAN could wield over regional initiatives from Canberra. Today, Wong says ASEAN is the ‘foundation’ of the effort to achieve ‘strategic equilibrium’ in the Indo-Pacific.

The Albanese government draws nourishment from Whitlam ideas while avoiding his ‘crash through or crash’ style. The US ambassador to Canberra, Marshall Green, called Whitlam a ‘whirling dervish’. In its rush, the Whitlam government was derided as being in office for a good time not a long time. Albanese aims to get a longer stretch in power, pointing to the model of Bob Hawke’s government.

One of the quiet tropes of the Hawke government in its early days was to size up a problem by asking: ‘What would Gough Whitlam have done?’ Then do the opposite. A quiet trope of the Albanese government is to ask, ‘What would Kevin Rudd have done?’ Then do the opposite.

Albo embraces Rudd substance while carefully avoiding the frantic style. One aim is to avoid having everyone in the prime minister’s orbit suffering permanent sleep debt.

During Whitlam’s time, the Canberra bureaucracy united in admiring his ambition while deploring the government’s internal ‘chaos’. The public service had a similar view of Rudd’s government, although the word for its internal workings was ‘dysfunctional’.

Still with the scars of those years, Albanese knows what he wants to avoid as well as what he wants. Six months in, the early public service judgement is ‘orderly’ and ‘disciplined’. The press gallery sees something similar in the relatively calm workings of parliament.

No matter how calm and disciplined you are, a dumper wave can still smash you.

Labor knows Whitlam’s three years in power were bedevilled by the slowing world economy, just as Jim Scullin’s Labor government (1929–1931) was hit by the times—taking office two days after the Wall Street crash, to be smashed by the Great Depression and party splits.

A looming global recession threatens to revisit the three-year hoodoo on Albanese. In the previous two decades, Australia decoupled from America’s economic woes. China lifted Australia over US economic crashes. The scenario may play differently this time if the US tips into recession.

The rhymes of history darken the dreams of the Albanese government.