Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The central guidance in the defence strategic review is the introduction of the concept of deterrence by denial. I and my co-author Richard Brabin-Smith argued for acceptance of this concept in May 2021 in an ASPI publication titled Deterrence through denial: a strategy for an era of reduced warning time. We maintained that deterrence was more likely to work if Australia had a more certain ability to deny an attacker its military objectives. Solid deterrence provides a hedge against surprise, raises the cost to an adversary of action against our interests and, if sufficient, makes an enemy’s attack irrational.

The bottom line for defence policy is that, as confidence in deterrence by denial goes up, our dependence on early response to warning should go down. Moreover, it would be easier and cheaper to go to a higher state of alert with this concept than with one based on deterrence through punishment, which implies attacking the adversary’s territory.

The review appears to accept this and focuses on deterring a potential adversary with long-range missiles in our area of primary strategic concern, which it defines as encompassing the northeastern Indian Ocean through maritime Southeast Asia into the Pacific, including our northern approaches. Of course, were an adversary to gain access to a military base in a place such as the Solomon Islands or Vanuatu, we would have to contemplate a threat to our heavily populated eastern approaches. We simply cannot revert to a defence force that can only defend Australia and our immediate region.

Some issues in the publicly released version of the review didn’t receive sufficient explanation. For example, why didn’t it make a recommendation about whether we should go ahead with the $50 billion Hunter-class frigate program rather than pass the parcel to yet another independent analysis? And why was the army’s bid for new Abrams tanks not cancelled?

The review says the defence organisation is facing significant workforce challenges (which Defence Minister Richard Marles acknowledges) and that’s a recurring theme across the Australian Defence Force, the defence public service and defence industry. This is an acute issue for Defence. Also, the growth in star rank levels (brigadier equivalent and above) has been astonishing over the past two decades—June 2022 figures are navy, 58; army, 86; air force, 61; and defence public service, 156. The review’s recommendation for a comprehensive review recommended of the ADF reserves, including consideration of the reintroduction of a ready reserve scheme, is a good idea.

Another important workforce issue is not mentioned. Under what conditions would we need to mobilise not only the ADF and its supporting public service, including the intelligence community, and how would nationwide mobilisation work in a real security crisis when there would be mutual competition for key staff between military, civilian, defence industry and reserve forces? The review has a chapter on force posture and preparedness, but it doesn’t address the issue of mobilisation at all, even though it’s in the terms of reference and the defence organisation has been working on such an analysis for several months.

The review strongly criticises the Defence Department’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, saying its approach to capability acquisition is not fit for purpose and ‘the system needs to abandon its pursuit of the perfect solution or process and focus on delivering timely and relevant capability’. It says Defence’s acquisition process is not suitable given Australia’s strategic circumstances and there’s a clear need for a more efficient process. The volume and complexity of projects is overwhelming Defence’s capability system, its limited workforce and its resource base, resulting in delays and ‘strategically significant capability outcomes not being achieved in a timely manner, or at all’.

The review recommended that Defence, ‘where possible, acquire more platforms and capabilities via sole-source or off-the-shelf procurement, and limit or eliminate design changes and modifications’. The review team said it had seen ‘evidence of contractors managing contractors through several layers of a project’s governance structure with inadequate Commonwealth oversight’. It stressed that mechanisms to manage risk in acquisitions ‘do not serve us well in the current strategic environment’ because they’re ‘burdensome and misguidedly risk averse’.

The review concluded that options should be developed as soon as possible to change Defence’s acquisition system ‘so that it meets requirements and is reflective of our current strategic circumstances’. But it doesn’t address the National Audit Office’s demands for suitable checks and balances on the process.

So, the review marks a significant break from most of Australia’s defence policies in the past 50 years and recognises the serious deterioration in our strategic circumstances. While reinforcing many of the changes set out in the 2020 defence strategic update, it also proposes important new directions for the ADF’s structure and posture. Because the public version omits sensitive material, some of its recommendations are more implied than explicit.

In some respects, it’s a pity that the review dropped the expression ‘defence of Australia’, for there remains much continuity in the new era with the earlier policies. The key change is that the notion of the ‘core force and expansion base’ is no longer valid. Instead, the central idea for today’s circumstances, when extended warning time no longer applies, is the need for a contingency force with a surge capacity. The review goes a long way towards recognising that, although its lack of discussion of mobilisation is a weakness.

Under the old policy regime, Australia was able to get away with a small peacetime defence force, at peacetime levels of preparedness, capable of little more than routine peacetime operations and training, supported by peacetime intelligence and policy communities and a peacetime industry base. Clearly, this is no longer appropriate.

The review indicates that readiness and sustainability are now major concerns, saying in effect that a platform without a crew or weapons is a waste of time and money. Its call for an increase in aircrew numbers is a serious indictment of current Defence culture. The review doesn’t indicate the costs involved but implies they’ll prove significant.

The review gives welcome support for the acquisition of uncrewed platforms (submarines and the Ghost Bat autonomous aircraft are mentioned) and for a program to build highly capable precision guided weapons in Australia. This will enable us to move quickly to implement deterrence by denial, especially through long-range precision missiles. And it offers a more convincing mode for timely force expansion than the previous, largely implicit assumption that force expansion would be through the acquisition of additional, complex and costly major platforms. It’s perhaps significant that the review doesn’t propose acquiring further major platforms beyond those already planned, although the recommended independent analysis of the Navy’s surface fleet could well propose such changes.

In many respects, the army will undergo the most significant change, entailing a refocusing of priorities. Why hadn’t Defence itself realised that the direction in which the army was moving wasn’t well matched to Australia’s emerging strategic circumstances? There’s an echo here of the factors that led to the need for the 1986 Review of Australia’s defence capabilities: issues even then concerning planning priorities for the army had been much more contentious than those for the navy or the air force, and they had been left unaddressed.

Nevertheless, the new and rearticulated responsibilities for the army will increase its importance and relevance. Land-based long-range anti-ship missiles will have a vital part to play in deterrence by denial. Handling the technological complexities of precision targeting will be made easier by the transition to the review’s culture of an integrated force. It will be important for army’s anti-ship missile units to be well supported by the navy and other defence elements. And the strengthened focus on littoral operations is clearly relevant to Australian priorities. It’s important that the limits to what is intended are spelled out, because if it’s taken to the extremes the resource demands would be unrealistic, and the priority doubtful.

Explicit in earlier policies was the expectation that intelligence analysis would warn that Australia’s strategic environment was deteriorating, and that government would act on that advice. We have been concerned for some years that the machinery of government was slow to recognise strategic change and even slower to act. The review reinforces this concern. Throughout, for example, it emphasises the need for urgency. And there are many other examples of its concerns about out-dated policies and priorities for resources.

These are issues of governance, not necessarily only within the Department of Defence. The review emphasises the importance of taking an integrated, whole-of-government approach to national defence—as in the review’s title. We are entitled to ask what’s been going on for this statement of the obvious to require such prominence.

Looking at past governance issues is useful because it’s important not to repeat past mistakes. But concerns go beyond this. The most recent review of the Australian intelligence community was in 2017, well before today’s security perspectives developed. It would be timely to be reassured that our intelligence community is well placed to meet today’s demands, including through having a surge capacity to deal with 24/7 contingencies.

For Defence, there’s no unique approach to governance, and practice has tended to reflect the issues and priorities of the day, going back to the reforms of the early 1970s under Defence Minister Arthur Tange. The most recent examination was the first principles review conducted in 2015, long before today’s strategic anxieties developed. These observations, together with the review’s telling criticisms of current practice and explanation of the difficulties that lie ahead in implementing its recommendations, reinforce the need for a thorough examination of governance, both within Defence and within the machinery of government more generally, to ensure that it’s fit for purpose in today’s changed circumstances.

The review is a major step along the road of much-needed reform and the key will be in implementing its findings. The government must avoid past failures of not following through on the program.

And as always there’s finding the money. Defence will have to ruthlessly weed out lower priority proposals. It is reassuring that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, when launching the review, acknowledged that increased defence spending would be required beyond the forward estimates. We must hope he keeps his word. History tells us that too often Defence has been a convenient milch cow when there are strong budgetary pressures elsewhere.

(A version of this article has appeared in The Australian.)

Critical minerals are the bedrock of the global economy, and they are crucial to the advanced capabilities relied on by the world’s top militaries. Metals like copper, nickel and cobalt are ubiquitous in the mechanised world, in everything from aircraft engines and electrical wiring to industrial machinery and electric vehicles. Yet reserves of minerals, and the places where they’re processed, are unevenly concentrated globally.

Given their necessity in the global economy and in the military balance of power, the US must adopt an expanded strategy for securing critical minerals. Complicating this matter, possible sources of critical minerals are in high-risk countries and are mined by non-American companies, often from China.

Indonesia produces 48% of the world’s nickel ore and Chinese companies are expanding their nickel dominance there, investing more than US$14 billion in projects over the past 10 years. Russia produces 17% of the world’s class 1 nickel, which is necessary for electric vehicle batteries, and China produces 20%.

The US holds only 0.4% (370,000 tonnes) of global nickel reserves, and it produces a mere 0.5% (18,000 tonnes) of the world’s nickel ore. The sole nickel-producing mine in the US—Eagle Mine in Michigan—ships its ore overseas for refining and is slated to close in 2025.

Annual US nickel consumption is around 80,000 tonnes, so even if it refined all of its ore production it would still need to import nickel. And even if the US mined all of its nickel reserves, at current reserve levels it would only have enough to last 4.6 years.

The US lacks enough of other critical minerals (such as gallium, graphite, yttrium, bismuth and rare earths) to be self-sufficient and must import them. But its allies also don’t have enough reserves, or don’t mine enough, to meet US demand. The US Geological Survey says China produces 70% of the world’s rare-earth ore, while the US and its allies produce 23%.

The US should be able to rely on its own product and that of its allies to satisfy its demand. But the allies producing rare earths often use them domestically or ship them to China for refining, limiting US access. Australian rare-earths miner VHM Limited, for example, will sell 60% of its output to Chinese rare-earth giant Shenghe.

To secure adequate minerals for its economy and military while it develops domestic production, the US must adopt a critical minerals strategy beyond ‘onshoring’ and ‘ally-shoring’. The government should support American companies financially to help them secure supply agreements with trusted companies, acquire existing overseas mines, and develop new mines overseas. Given the scarcity of experienced, well-capitalised US mining companies, major and junior companies from Canada and Australia should be eligible partners with US firms in this strategy.

A first step would be for the US government to establish a list of companies from which American companies could source minerals—as in manufacturers of rare-earth magnets purchasing oxides from Australian company Lynas’s facility in Malaysia.

Buying existing mines has the advantage that they have proven production, and Canadian and Australian mining companies are already doing this. Australian company Rio Tinto recently secured direct control of Mongolia’s Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine. To further reduce supply risk and strengthen economic partnerships, the US government can work with the host country government to identify mines for acquisition, help finance the purchase by US companies, and establish processes to resolve any disputes.

Developing mines costs billions of dollars up front, and securing that capital at reasonable rates, especially for projects in high-risk countries, is difficult. The US government could provide cheap capital for US companies to develop such mines. US companies could partner with Canadian and Australian companies seeking to develop overseas mines, such as BHP, which has invested $40 million in Tanzania’s Kabanga Nickel project.

A US company could identify a project and seek the US government’s financial support and help in negotiating with the host country to secure the mining concessions.

Australia’s deputy prime minister and defence minister, Richard Marles, opened ASPI’s Sydney Dialogue with a warning that Australia must establish a much stronger technological base. An edited version of his speech follows.

Can I start by acknowledging the Gadigal people, the traditional owners of the land on which you are all meeting this morning. And let me also acknowledge the Ngunnawal people, the traditional owners of the land from which I speak to you, right now.

And in acknowledging both, say how proud I am to be a part of a government which is completely committed to seeing our First Nations peoples recognised in our constitution through the establishment of a Voice to Parliament. Later this year, Australians will be given the opportunity of placing their vote in support of that recognition.

Climbing the technological ladder is really Australia’s great challenge.

And it is particularly our challenge, more our challenge than almost any other country in the world.

The Harvard Index of Economic Complexity is a measure that has at one end of the spectrum the most high-tech sophisticated services economy, which happens to be Japan. And at the other end, the most basic subsistence economy, it is, in many respects, an index of modernity—an index of technology.

Right now, Australia ranks 91st on that index. We are sandwiched between Namibia and Kenya.

And while that’s obviously not a true reflection of where we stand in the list of modernity in the world, it does speak to the fact that as an economy we are highly dependent upon our primary industry.

Now, primary industry is really important for our country and right now it is the hope.

But we as a nation must be more than that.

And that really means that we have a national challenge to climb the technological ladder, and in the process, change our relationship, our cultural relationship to science.

In many respects, I think there is no greater microeconomic reform in Australia today than infusing our economy with science and technology, which is why what you’re talking about over the next two days [at the Sydney Dialogue] is so profoundly important for our country.

And while we have a proud history in science and in discovery, as commercialisers of that science, of infusing it into our own economy, we do poorly relative to other developed nations, and this we must change.

That is a challenge across our general economy. But it’s also a fundamental challenge in respect of our defence industry.

And it’s essential to advancing our national interest in the world that we climb the technological ladder when it comes to defence industry. Because in so many ways, the history of human contest is ultimately a history of technology competition. And we must be at the forefront of that.

As [ASPI executive director] Justin [Bassi] said, the AUKUS announcement, and the technology-sharing arrangements embodied in AUKUS between Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom, are very central to our strategy in terms of improving the technology within our defence forces and within our nation’s defence industry.

Certainly, acquiring a nuclear-powered submarine capability for Australia and becoming just the seventh country in the world to be able to operate that technology will be a very significant step forward in capability for our nation.

But the pillar two area of AUKUS, which seeks to look at other emerging technologies, is going to be fundamentally important for our nation as well. In areas such as hypersonics, artificial intelligence, quantum; making sure that we are at the forefront of all of that is critically important in terms of making sure that when it comes to human contest, we are right there with a technological edge.

And this is very central to how we are thinking about our strategic circumstances and how we’re thinking about advancing our national interests in the context of those strategic circumstances.

So, I really wish you all the best for the coming two days. It’s important that we are talking about what technologies we can bring to bear within our wider economy and certainly within our defence industry.

But as we think about the new technologies which are out there, and the new technologies that we can infuse within our economy, it’s also really important that we are not just having another conference about new technologies, but that we are having the conversation about Australia’s relationship to technologies.

That’s actually what we have to change. We need to be thinking about how Australia specifically should be and absolutely can be at the centre of global technology advancement. To say that is our great national challenge.

And with that, I really wish you all the best for the coming two days.

And I hope the Sydney Dialogue fulfils all the promise that you have for it.

At the Quad foreign ministers’ meeting on 3 March in New Delhi, the four principals reaffirmed their countries’ ‘steadfast commitment to supporting a free and open Indo-Pacific, which is inclusive and resilient’. Held a day after the G20 foreign ministers’ meeting, it showcased the vigour of the Quad—an informal minilateral framework of like-minded partners—despite differences over the conflict in Ukraine.

As in the past, the elephant in the room continued to be China.

Beijing’s revisionism and attempts at hegemony have fast-tracked the Indo-Pacific ideation of an aspirational, rules-based regionalism, and cemented the constellation of Australia, India, Japan and the United States. Indeed, China has unintentionally become the matchmaker for Australia and Japan’s blossoming relationship.

As what the late Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe called ‘neighbours at a longitude of 135 degrees east’, Australia and Japan now form the regional cornerstone that assures peace and stability in the Western Pacific. As democratic sea-faring powers, the two partners share a similar strategic outlook. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has brought them closer in their world views.

Adding volatility to complex geopolitical conditions, the combined effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have set a new stage for Australia and Japan by clarifying the perspectives of their Indo-Pacific strategies. The two must exploit this new international environment to safeguard peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific now that as China and Russia have, albeit differently, revealed their Achilles’ heels of strategic failures and structural weakness.

As members of the Quad, both states have flexibly explored multilayered collaboration with various partners within and outside the Quad. Bound by economic interdependence, geographical proximity and strategic convergence, both Australia and Japan have the means and willingness to realise a rules-based Indo-Pacific.

Conscious of their critical responsibility, Canberra and Tokyo have begun to show the resolve needed for joint efforts. Meeting in the Indian Ocean city of Perth in October last year, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his Japanese counterpart, Fumio Kishida, released a compelling joint statement and issued a renewed joint declaration on security cooperation.

This, of course, came as an extension of the reinforced bilateral ties from the last decade. In defence cooperation, the two governments concluded an enforced acquisition and cross-servicing agreement and a reciprocal access agreement. For Japan, Australia is becoming close to an ally, second only to the US.

The complementary roles the two governments can play in reaching non-aligned states is critical as the ‘global south’ becomes a powerful megaphone to voice concerns in a fractured, multipolar world.

The good news is that both Tokyo and Canberra possess great strengths in their respective regions. Japan, for instance, can act in areas where Australia is less present such as Africa and Eurasia.

Yet their outlooks also converge in much of the Indo-Pacific. For example, the Partners in the Blue Pacific—a minilateral platform comprising Australia, Japan, New Zealand, the UK, and the US, established last year—aims to work closely with the Pacific Islands Forum. This is one more welcome development in the Pacific that will accompany Canberra’s and Tokyo’s enduring efforts.

Reaching out to ASEAN by embracing its centrality and engaging with its members matters. With the likely exception of the Philippines, coalition-building with ASEAN is largely stalemated as its members continue their strategic hedging between Beijing and Washington.

None are better placed to break this gridlock than Australia and Japan because of their economic ties and trusted engagement with the region.

Bringing Southeast Asian states ‘in’ to the Indo-Pacific is essential for peace and stability in the Western Pacific. But in the absence of a collective defence mechanism and given the Quad’s contextual limitations, the US-led security architecture will necessarily play the major role in an armed conflict scenario involving China and Taiwan. Nevertheless, support from ASEAN countries is imperative.

In military terms, on top of the US–Japan, ANZUS and AUKUS alliances, the lynchpin regional architecture remains the longstanding trilateral of Australia, Japan and the US, which frequently holds consultations and conducts drills. Buttressing the US hub-and-spokes system as part of a networked security architecture, Australia and Japan are vital guardians of regional peace.

There’s little doubt that Australia, as the National Security College’s Rory Medcalf says, is an ‘Indo-Pacific bellwether’. So, too, is Japan. With a moderate, benevolent image, the duo can better lead the cause for a rules-based order―a task the larger, hard-charging US often finds difficult.

The Quad leaders’ summit, to be held in Sydney next month, will further confirm their shared values and interests. The time is now for Australia and Japan to enter the new Indo-Pacific stage. In tandem with their partners and to keep their region free and open, the two must craft and carry out a politically astute geostrategy that responds to the requirements of our time.

The issue of nuclear non-proliferation is back in the headlines, thanks to details announced last week about Australia’s acquisition of nuclear submarines under the AUKUS pact.

The deal, which may cost Australia upwards of $300 billion over the next 30 years, involves Australia purchasing three Virginia-class nuclear-powered, conventionally armed submarines by the early 2030s. Australia will also build its own nuclear-powered submarines using US nuclear technology by the 2050s.

Australia, the UK and the US have said the deal complies with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.

But China has said the AUKUS deal represents ‘the illegal transfer of nuclear weapon materials, making it essentially an act of nuclear proliferation’.

So what are Australia’s obligations under the nuclear non-proliferation regime and does this deal comply?

To answer this question, you need to know a bit more about two key treaties Australia has signed up to: the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (sometimes shortened to NPT) and the 1986 Raratonga Treaty.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty essentially requires nuclear-weapon states that are a part of the treaty (the US, the UK, China, Russia and France) to not pass nuclear weapons or technology to non-nuclear-weapon states. (Of course, other countries do have nuclear weapons but they aren’t part of the treaty.)

Crucially, the treaty only relates to the use of nuclear materials associated with nuclear weapons. It has a specific carve-out in it for the provision of nuclear materials for ‘peaceful purposes’ (in Article 4).

The treaty also outlines processes to ensure the International Atomic Energy Agency monitors nuclear programs and nuclear materials even if used for peaceful purposes (including uranium and the technology to use it).

Australia has a number of subsidiary arrangements with the International Atomic Energy Agency that outline how these safeguard arrangements work.

Despite what critics may say, Australia’s nuclear-powered engines under AUKUS comply with the written rules of the treaty and these subsidiary agreements.

On the face of it, you might think the term ‘peaceful purposes’ would rule out use for military submarine propulsion. But the definition focuses on using nuclear material for purposes that don’t involve the design, acquisition, testing or use of nuclear weapons.

All AUKUS partners have emphasised that the nuclear-powered submarines Australia is to acquire will only carry conventional weapons, not nuclear weapons.

Australia’s agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency clarifies what is covered by the treaty and the concept of peaceful purposes.

Article 14 of this agreement says ‘non-proscribed military purposes’ are allowed.

Effectively, the Australian government has interpreted this to mean that nuclear materials can be used for naval nuclear vessel propulsion. That is a usage unrelated to nuclear weapons or explosive devices.

Some have suggested this argument creates a risky precedent that nuclear materials—beyond the supervision of the International Atomic Energy Agency—could be used to make weapons.

But Australia has undertaken to comply with its safeguard obligations with the International Atomic Energy Agency for the AUKUS deal. This builds on its existing practice related to nuclear materials held for other ‘peaceful purposes’ (like research and medical uses).

Australia is also a signatory to the Raratonga Treaty (also known as the South Pacific Nuclear-Free-Zone Treaty), a regional agreement that supports the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Signatories to the Raratonga Treaty have effectively agreed to maintaining a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the South Pacific.

The Raratonga Treaty entered into force in 1986. It provides that no ‘nuclear explosive devices’ can enter the nuclear-free zone outlined in the agreement. It also includes other limitations on the distribution and acquisition of nuclear fissile material (which are materials that can be used in a nuclear bomb) unless subject to specific safeguards.

The Raratonga Treaty accounts for differences in opinion about Australia’s and New Zealand’s approaches to vessels carrying nuclear weapons (New Zealand doesn’t allow nuclear-weapon-carrying vessels to visit its ports, while Australia does).

But more importantly for the AUKUS deal, this treaty doesn’t strictly exclude a signatory from using nuclear propulsion. That’s as long as the engine isn’t considered ‘a nuclear weapon or other explosive device capable of releasing nuclear energy, irrespective of the purpose for which it could be used’.

Provided the engines meet this definition, the AUKUS deal complies with the Raratonga Treaty as well.

Australia will have particular obligations under this treaty to deal with the nuclear waste. Defence Minister Richard Marles has outlined that waste from the vessels will be kept on Department of Defence land on Australian territory (and not disposed of at sea).

More detail is still to come. But the US and UK have decided that the risks involved in sharing nuclear-propulsion technology with Australia are worth it to hedge against a more aggressive China.

On the face of the announcements made so far, the deal complies with international law, despite accusations to the contrary from China and other critics.![]()

Climate action isn’t just an environmental obligation but is now central to Australia’s diplomatic strategy and national security, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said in a speech at the National Press Club last month.

Albanese’s comments underline the imperative for Australia to step up its regional diplomatic engagement on so-called soft security issues, while also addressing hard security challenges through mechanisms such as AUKUS.

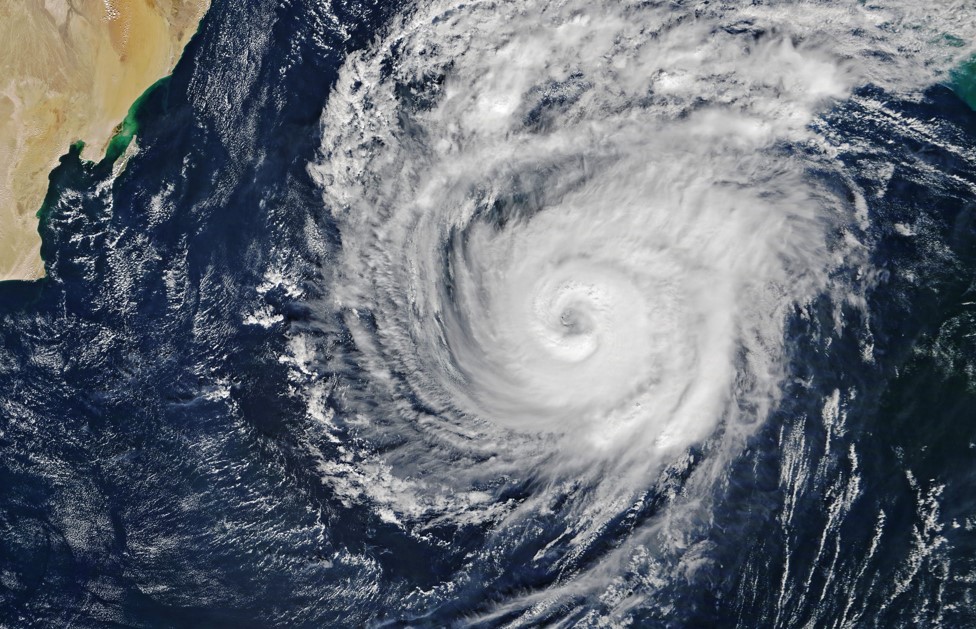

Nowhere is that judgement more relevant than the Indian Ocean region, where Australia and its partners are facing a highly unstable future. In addition to growing strategic competition between major powers, the region faces multiple challenges that threaten its security and stability, including civil conflict, terrorism, piracy, people smuggling and illegal fishing.

But the biggest non‐military threats to regional security will come from climate change and the impact of other human activities on the natural environment.

The threats include sea-level rise, severe weather events such as cyclones and storm surges, marine heatwaves, loss of primary producer habitats and organisms due to ocean heating (for example, coral bleaching) and ocean acidification. Shipping accidents, including massive oil spills, also threaten to wreak havoc on island states whose economies are highly dependent on fishing and marine tourism.

These effects are likely to act as multipliers, exacerbating water, energy, food and health challenges that diminish resilience and increase the likelihood of conflict. Sadly, the trend is mainly in the wrong direction.

For many of Australia’s smaller and most vulnerable neighbours, particularly the island states, climate and environmental security threats are their highest priority. For all, it threatens their economic, social and political security, and for some it represents an existential threat. If we want to properly engage with our neighbours, we need to focus on the issues that matter most to them.

Australia should implement a coherent approach to Indian Ocean environmental security as part of an integrated Indo-Pacific strategy. Commendably, Australia has pursued elements of such a strategy with some success in the Pacific, particularly under the Albanese government. But we’re a long way behind in the Indian Ocean, Australia’s often neglected second sea.

It’s no longer good enough to adopt a business-as-usual approach to these problems on our western front. Just as climate change is now a central element in our engagement with the Pacific island states, environmental security should be a key pillar in our engagement with our Indian Ocean neighbours.

Unfortunately, in the Indian Ocean—unlike in the Pacific—there are no effective regionwide mechanisms to facilitate cooperation on policy formulation on climate change or to coordinate responses to different types of environmental security threats. And there’s no reason to believe that groupings in the region will be in a position to take effective action on these issues anytime soon.

The region also lacks an organisation dedicated to advancing environmental security capabilities through professional development for civil and military officials that are responsible for environmental policies and responses. In the Pacific there are regional arrangements that play important roles in professional development in areas such as environmental issues, fisheries governance and law enforcement. But there is nothing comparable in the Indian Ocean.

Our new report, Good neighbours: strengthening environmental security in the Indian Ocean region, makes two key recommendations for Australian-led initiatives in the Indian Ocean.

First, the Albanese government should work with key regional partners to promote an Indian Ocean dialogue on environmental security. This mechanism would include regular meetings at ministerial and senior-official level to develop shared perspectives and coordinate responses to climate change and other environmental security threats.

The dialogue would also provide a platform for Australia and its partners to work together to develop response arrangements for different types of environmental threats ranging from severe weather events to the prevention and mitigation of oil spills and other shipping accidents.

We recommend that just before the senior officials’ meeting, there should be a track 2 meeting of key stakeholders from around the Indian Ocean region and elsewhere, including representatives from academia, science, business and non-government organisations. It would provide a platform for civil-society stakeholders to provide input to the senior officials’ meeting.

The dialogue should start out with key partners such as India and France and other selected countries that prioritise climate action. It would then be built up to include other interested partners.

We also recommend that Australia sponsor the establishment of an Indian Ocean centre for environmental security to provide professional development and training to personnel from civil and military agencies across the region. It might also undertake collaborative applied research on current and projected environmental security threats.

The proposed centre would serve as a knowledge hub and information conduit, including for capacity development in environmental security across the Indian Ocean.

It should receive its core funding from the Australian government, supplemented by funding from key partners. This would demonstrate Australia’s commitment to the region and send a clear message that we are giving priority to the environmental security challenges faced by our partners. The centre should be based in Perth to reinforce the city’s status as Australia’s gateway to the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean region is faced with a wide range of increasing environmental threats. That’s going to require Australia to take a much more active role. We can’t afford to just muddle through when it comes to the security, sustainability and stability of our region.

With Richard Woolcott, you always had to take the smooth with the smooth.

No rough edges for this wattle-proud Australian who was one of our greatest diplomats. His smarts and his steel always presented in suave and subtle hues.

Woolcott encapsulated Australia’s major diplomatic ambition—then and now—in a single phrase. In Asia, he said, we must be ‘the odd man in, not the odd man out’. Typical Dick Woolcott—the central point offered with an optimistic up beat, accompanied by the broadest of smiles.

On Woolcott’s death in Canberra last week at the age of 95, the plaudits aimed high: a ‘legend’, a ‘diplomat’s diplomat’, a ‘giant’.

As a happy warrior, Woolcott used a jest to open his memoir about his 40-year career from diplomatic cadet to department head. He recalled walking into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in 1988, shortly after he’d been appointed its secretary, accompanying the new foreign minister, Gareth Evans:

Beside me, Gareth asked: ‘How many people work here?’

‘About half,’ I replied. ‘But between us we can change that.’

It was a quip about an institution that defined his life. Woolcott talked of ‘the department’ with a mixture of affection and exasperation and enjoyment.

After the serious business of the memoir reflecting on diplomacy from Joseph Stalin’s death to the Bali bombings, Woolcott produced a second book on the lighter side of international life, Undiplomatic activities, filled with anecdotes and tall tales (and launched by former prime minister Bob Hawke on the sidelines of the APEC summit in Sydney in 2007):

Required not only to sacrifice a settled home life in the service of their country, diplomats must also heroically offer up their livers to booze, their stomachs to endless official dinners, their integrity to dangerous liaisons and the weasel art of spin, and their sanity to the pomposity and weird protocols that are an integral part of the international scene.

In explaining those weird protocols, Woolcott several times quoted to me a maxim of another Australian mandarin, James Plimsoll: ‘A decision not to make a decision is definitely a decision.’ Woolcott’s character, though, pushed against no-decision havering.

See Woolcott’s smarts and steel in the two issues he nominated as the most high profile of his career: the ‘disappointing and negative’ experience of East Timor and the creation of APEC (‘an important foreign and trade policy success for Australia’).

As Australia’s ambassador in Jakarta when Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975, Woolcott and the Australian embassy were better informed about Indonesian military’s plans than Indonesia’s foreign ministry. Even critics who said that Australia’s close knowledge became silent acquiescence recognised the professional brilliance of the Australian embassy’s work, and its intelligence coup in giving Canberra three days’ advance notice of the time and place of the Indonesian invasion.

On 5 January 1976, Woolcott sent a long dispatch from Jakarta on ‘Australia, Indonesia and East Timor’ that became one of the most notorious leaked telegrams in Australian diplomacy.

No matter how unjust the invasion may seem, Woolcott wrote, ‘Indonesia could not have been diverted from this course by Australia.’ Canberra must accept the reality of Indonesia’s incorporation of East Timor, he advised:

It is on the Timor issue that we face one of those broad foreign policy decisions which face most countries at one time or another. The government is confronted by a choice between a moral stance, based on condemnation of Indonesia for the invasion of East Timor and on the assertion of the inalienable right of the people of East Timor to self-determination, on the one hand, and a pragmatic and realistic acceptance of the longer term inevitabilities of the situation, on the other hand. It’s a choice between what might be described as Wilsonian idealism or Kissingerian realism. The former is more proper and principled but the longer term national interest may well be better served by the latter. We do not think we can have it both ways.

The following month the cable was leaked and was on the front page of the Canberra Times. A former Labor leader and foreign minister, Bill Hayden, commented decades later that Woolcott was guilty of writing too vividly in tendering advice. Diplomats, Hayden observed, need to use more obscure language when dealing in ‘realpolitik’.

The creation of APEC in 1989 played to Woolcott’s vision of the central place of Southeast Asia (and Indonesia) in Australia’s Asia destiny.

For Australia, ASEAN held the crucial cards in the effort to form APEC. The initial omission of the United States from the core membership proposed by Prime Minister Bob Hawke in floating the idea reflected this concentration on East Asia. A masterstroke in the diplomatic dance was the dispatch of Woolcott in April 1989 as the prime minister’s emissary to the (then) six ASEAN capitals, plus Tokyo and Seoul.

Woolcott went first to Indonesia, showing deference to Suharto as ASEAN’s central figure. He told Suharto that Australia had come for advice and guidance on how a new regional body should proceed. Woolcott wrote that it was essential to get ‘Suharto’s support or at the very least his interest and acquiescence’.

The reward for this proper show of respect to ASEAN’s leader was an expression of Suharto’s willingness to think about the idea. Armed with that relatively neutral Indonesian position—APEC was an interesting proposal worth discussing—Woolcott then travelled through the rest of Southeast Asia building Suharto’s half-nod into a consensus that overcame Malaysia’s strong opposition.

Malaysia’s prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, had wanted to kill the APEC concept in embryo, seeing it as a challenge to ASEAN. Malaysian officials complained at the skillful way Woolcott played his ASEAN cards, claiming that Suharto’s simple expression of a willingness to listen had been used to leverage stronger endorsements from the rest of ASEAN. Certainly, Woolcott had made full use of the guidance he received from Suharto and the fact that there was no Indonesian veto.

Woolcott’s shuttle diplomacy was a bravura performance of the art he described in his memoir:

The instruments that Australian ministers and diplomats need in efforts to secure our national future are in the main the capacity to persuade and to influence. In other words, we need competent, professional and effective advocacy and diplomacy backed, of course, by public support for the government’s policy, as well as credible defence capability in the background. Diplomacy is really the art of persuasion and accommodation and of building support in other countries for one’s policies. Very rarely can diplomacy be used to impose a purely national pattern of activities on the international community.

Dick Woolcott saw good diplomacy as a key asset for the country he loved to negotiate its place as the ‘odd man in’—Australia must be an integral part of the Asia that he loved.

The language Australia uses today about the centrality of ASEAN to the Indo-Pacific draws on the vision of earlier ASEANists such as Woolcott. That’s an important legacy from a great Australian who was a great diplomat.

It’s been just over a month and a half since Fiji’s new coalition government, headed by former coup leader Sitiveni Rabuka, was sworn in to parliament. The December election was a tight race, as many had predicted, and Rabuka’s former party, the Social Democratic Liberal Party (SODELPA), was dubbed ‘kingmaker’ when its eventual support for Rabuka ended Frank Bainimarama’s 16-year premiership. Australia’s relationship with the new government appears to be positive, but we must ensure our support continues to be Fiji-focused regardless of who’s leading the country.

Rabuka and his coalition have hit the ground running, making sweeping changes that have caused a few tense moments. He is loosening a restrictive media act, and Fiji Broadcasting Corporation CEO Riyaz Sayed-Khaiyum (a brother of former attorney-general Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum) has been removed. The government has welcomed back exiled officials and is reviewing diplomatic appointments to ensure they represent the needs of the government. Rabuka has also set up the Mercy Commission, which was written into the 2013 constitution but never convened, to review the cases of those who have been incarcerated for a very long time. That process may lead to the release from prison of yet another coup instigator, George Speight.

Some are concerned that in moving so quickly the coalition may leave itself open to having its changes invalidated if the correct legal processes aren’t followed. Others believe that the new government is going too far too fast. The commander of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces, Major General Jone Kalouniwai, publicly outlined his concerns with the new government, citing his responsibility to do so given the military’s self-proclaimed role as ‘guardian’ under the Fijian constitution.

After 16 years of one government, there’s little cabinet experience in the coalition. Rabuka has admitted that some mistakes will be made—or, as Home Affairs Minister Pio Tikoduadua said after a damage-control meeting with Kalouniwai, ‘We are all learning.’ It was a moment of tension, but Rabuka and Tikoduadua settled the simmering pot before it boiled over. With many campaign promises still to be delivered, however, there could still be more sticking points to come.

As would be expected, the opposition—namely, Bainimarama and his right-hand man Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum—wasted no time in ridiculing the government’s every move. Bainimarama could seize power through a motion of no confidence, so Rabuka will have to ensure he keeps SODELPA onside after initially rewarding the party with key ministries and positions. But Bainimarama’s absence hasn’t necessarily left the gaping hole that it could have. In fact, Rabuka has returned to power relatively seamlessly after 23 years.

Rabuka also inherited the role of Pacific Islands Forum chair, at least until the position transitions to Cook Islands in March. The short timeframe means expectations on Rabuka to achieve much in the position were minimal. But he was quick to make a statement by travelling to Kiribati in January on his first overseas trip that he was intent on bringing it back to the fold. In what can only be deemed a major win for unity in the region, Rabuka came home successful in facilitating Kiribati’s presumptive return to the forum. His success demonstrates that Fiji will be no less influential in the region under Rabuka’s leadership than under Bainimarama’s, and perhaps even more so.

Looking further out in the region, last week Rabuka announced that he will terminate the memorandum of understanding between the Fiji Police Force and China’s Ministry of Public Security that has been in place since 2011. He explained that there was no need for the policing relationship to continue because the two countries’ ‘systems of democracy and justice systems are different’. In the meantime, both Rabuka and Tikoduadua have expressed a desire to deepen Fiji’s relationship with Australia, New Zealand and the US based on their having similar systems.

At the same time, police commissioner Sitiveni Qiliho was suspended from his role, as was the commissioner of corrections, Francis Kean. Both have strong ties to Bainimarama—Kean is the former PM’s brother-in-law—and questionable backgrounds to say the least. China’s policing assistance in the Pacific, which Qiliho was closely involved with for the past six years, has vastly more authoritarian characteristics than that of Australia or New Zealand. The decisions to remove the two commissioners and tear up the agreement with China were partly to demonstrate this change to a domestic audience and partly to send a clear signal to foreign partners about where Fiji’s values lie, and that aid and assistance must align with those values.

It’s a welcome statement for Australia and New Zealand, which are also seeking to highlight the values shared among all countries in the Pacific neighbourhood. In a joint visit to Fiji this week by the Australian and New Zealand defence chiefs, New Zealand’s CDF, Air Marshal Kevin Short, reiterated the importance of respecting Fiji’s values and ways of operating. Australia will now need to ensure that the new Fijian government is not left unable to fill any capability gaps that might arise in the Fiji Police Force.

Even though the policing agreement has been terminated, China is unlikely to turn away from Fiji. Instead, Beijing will probably continue to aggressively pursue friendship and look for other areas to deepen the relationship with the new government. Even Tikoduadua’s decision to meet with Taipei before Beijing won’t halt the Chinese Communist Party’s advances. Rabuka’s government will have to find a way to hold to its values without sacrificing a large economic partner.

Australia and other democratic partners should focus on supporting the coalition government in its efforts to strengthen Fiji both domestically and regionally. When Rabuka travelled to Kiribati, he flew on a Royal Australian Air Force plane, and the iconic kangaroo roundel featured in the background of some fantastic photo opportunities that had a wide reach across the region. Actions like this demonstrate that Canberra is interested in supporting the success of the region without needing to be at the forefront of issues.

As Rabuka’s coalition powers ahead, intent on moving past the policies of the previous government, there remains a risk of discontent if the population feels left behind. Australia must remain focused on supporting Fiji as a whole, and find a delicate balance between supporting the democratising instincts of the new government and not sullying the record of the previous prime minister, with whom we built a close partnership, and who might return.

From its inception, the AUKUS pact has been wrapped in expectations. Fundamentally, it is a technology and capability agreement—an accelerator.

That may sound mundane but it is incredibly challenging. To realise its promise, three sovereign nations, Australia, the UK and the US, need to align their capability development, collaborative research and respective defence industrial bases.

Let’s leave the submarines to one side—this article concerns pillar two of AUKUS, the technology programs, which are arguably of greater potential value over the long-term.

In the past, a defence technology agreement would be allowed to progress at a measured pace, with committees and considered research proposals in the respective defence science organisations.

But tightening geopolitical circumstances demand urgency: AUKUS needs to deliver. Politicians won’t be able to wait for favourable winds but need to begin today to do the heavy lifting of organisational change, budget prioritisation and making the case to sceptical electorates.

Australia is the smallest partner, the most exposed geopolitically, and the most in need of a technological uplift. It has the most to gain from AUKUS but only if it is prepared to make the greatest effort. Sustained Australian political investment in the program has to be matched by directed, ongoing financial support and structural change.

Funding has one of two sources: supplementation through the federal budget process or from within Defence’s existing budget. Both, of course, mean the taxpayer pays.

Prospects of supplementation from the budget are slim. Though the Labor government has endorsed AUKUS, and concerns are growing over the strategic environment, defence warranted only passing mention in the October 2022 budget. Defence is not where government wants to spend any spare cash.

Not that there’s much to be had. The federal budget is under significant pressure—measured against expectations, it always is. But worsening economic conditions—inflation, rising interest rates and a slowing Chinese economy—are adding pressure just as public sector demand is increasing.

Further, government debt, mostly assumed during the Covid-19 pandemic and at its highest level since World War II, was locked in with comparatively low interest rates (though interest payments are projected to rise significantly).

That’s the good news. Now that rates are rising with the need to control inflation, any further debt will be more costly. And while current levels of debt are manageable, prudence suggests paying it down quickly to allow manoeuvring room for the unexpected in a volatile environment.

Given that, it’s of little surprise that Treasurer Jim Chalmers is looking to the private sector to ‘co-invest’. But let’s be clear: while industry has a role, we should not kid ourselves that industry will pony up to meet shortfalls in defence funding. Companies aren’t charities.

In short, any new initiatives, or shifts in priorities, to fund AUKUS projects—including the submarines—will need to come from within existing Defence funding.

That’s going to be tough. The defence strategic review is likely to try to prod Defence into shifting some priorities. But the way Defence is funded—managed largely by itself within an agreed envelope—though tactically convenient, can make it hard to turn the ship of strategy. The internal momentum of existing programs and invested constituencies often outweighs any prospect for change.

New capabilities, like missiles, are welcomed—provided they do not upset the existing order. Politicians are wary of being labelled anti-Defence and so are reluctant to force choices, regardless of need. Consequently, the capability equation within Defence is one of replacement and summation, not transformation.

The final concern about AUKUS funding is the role of the Defence budget in the broader budgeting effort. Simply put, the Defence budget functions as a balancing factor.

Defence is the last portfolio considered in the round of expenditure committees that shape the budget. By then the government knows how much it may need Defence to forego from its envelope over the forward years to offset other budget priorities.

When slicing happens, the programs most at risk are those without an internal service constituency, such as pillar two of AUKUS.

What can be done to help realise the promise of AUKUS?

First, independent funding. A fund for AUKUS pillar two needs to be carved out of the Defence budget and administered separately.

Consider it a future fund for Defence—but one concerned with the here and now, drawing on the breadth of government, not simply the Defence portfolio. After all, the AUKUS technologies involved are not the sole preserve of the military but are inherently civilian.

Second, explicitly embrace dual timelines—short- and medium-term.

In the short-term, focus on what can be done now, with existing capabilities and technologies, for deployment in three to 12 months.

Recombination is common in the commercial sector. It is fundamentally an engineering and product, or capability, manager effort. In business, it can be found in fablabs and hackathons and the continual experimentation of lean start-ups.

The medium-term needs to consider translation of current applied research into capability deployable in the 12-to-36-month window, supported by a broader ecosystem.

Last, create new governance arrangements.

There are two parts to AUKUS pillar two: broad exploration and rapid translation. Neither are suited to the existing frameworks and culture of Defence—or the Australian Public Service, for that matter. Keeping pillar two behind the high walls of Defence will drive up costs and starve any prospective innovation system.

A new approach is needed, especially if AUKUS is to be part of a nation-building effort, to help enforce an AUKUS-by-design ethos, and avoid unwarranted taxpayer subsidisation of industry. In an economy built around extractive industries, that task should not be under-estimated.

At a time when the government is seized with social and economic change and debt is already high, the cost of realising AUKUS will be taken from within Defence. We’ve yet to see whether ministers have the stomach for the shaping and sustained effort needed to realise the pact’s potential.

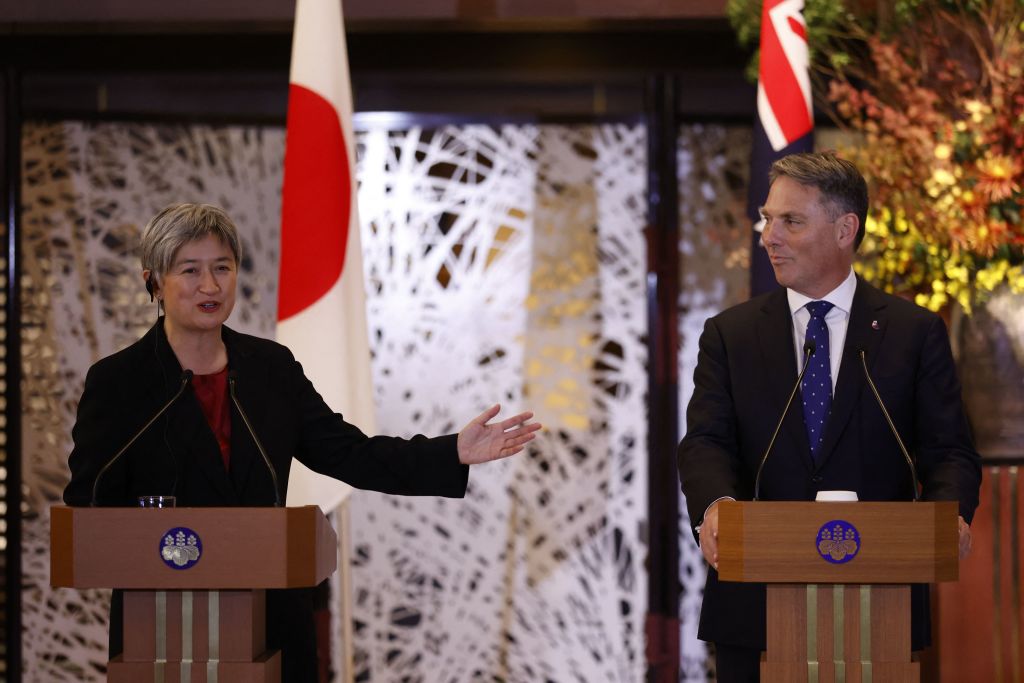

This week, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Defence Minister Richard Marles will travel to Europe for separate ‘2+2’ meetings with their French and British counterparts. Wong will also head to Brussels to meet the EU’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell. And Marles will travel on from Europe to Washington to meet US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin.

This visit is timely. The coalition effort to arm Ukraine has stepped up ahead of offensives anticipated in the northern hemisphere’s spring. Closer to home, Marles is expected to make significant announcements on the future of AUKUS and Australian defence policy in March.

With so much in play, each leg of this trip risks becoming dislocated and overly focused on the bilateral relationship at hand. Wong and Marles should strive to identify common threads connecting these relationships and their place within the wider strategic picture.

One strategic thread is AUKUS.

Part of Marles’ time with his British and US counterparts will be set over to the forthcoming announcement of the pathway towards Australian nuclear-powered submarines. But the AUKUS subs are unlikely to be the all-encompassing topic some expect. High-level discussions are probably more collegiate and less in the weeds of design options for the vessels than pundits like to imagine.

Beyond AUKUS, the focus on ‘modernising’ the Australia–UK relationship resonates with ‘operationalising’ the Australia–US alliance, which outgoing Australian ambassador in Washington Arthur Sinodinos said was the theme of the AUSMIN 2+2 in December. The logic is compelling: the world has changed, so Australia’s closest partnerships must evolve to deliver tangible outcomes at increased tempo.

The sequencing of these dialogues is important, as France—and Europe as a whole—has a stake in AUKUS, despite not being party to it.

Given the sense of betrayal left by the original AUKUS announcement that saw the dumping of the French Attack-class submarines, Australian ministers will feel obliged to brief French counterparts about the latest developments. There is a lot at stake for Canberra, including cooperation in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and trilaterally with India. Thankfully, the foreign minister’s media release augurs well, saying that the Australia–France 2+2 aims to ‘progress works towards a bilateral roadmap’. This might become the centrepiece of President Emmanuel Macron’s expected visit to Australia later this year. Further out, and with different branding, it might even be possible to include France in some of the advanced technologies under AUKUS’s so-called pillar two.

Despite improving relations, France’s initial outrage still taints some European views of AUKUS, as I heard when visiting Brussels last week. Wong’s meeting with Borrell is an opportunity to straighten out the record. But there’s no substitute for sustained engagement across European capitals. At the heart of EU and NATO decision-making are their member states, acting through the European Council and the North Atlantic Council respectively. Not all roads lead to Brussels when Canberra seeks to influence EU and NATO policy.

Which segues to the second strategic thread: the growing linkages between Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic security.

There is already broad and growing consensus among friends on this point. Wong, Marles and their British and French counterparts can probably all agree with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken that China must learn the right lessons from Ukraine—namely that smaller countries, like Taiwan, can be expected to defend themselves rigorously and attract support for their defence, and that aggression will be collectively punished, including through sanctions and the redirection of trade and investment. The 2+2 joint statements should be explicit about the strategic implications of Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Marles and Wong can point to Australia’s support for Ukraine as evidence that Canberra is putting resources behind its interpretation of interconnected regions. Australian pledges to Ukraine—now approaching half a billion US dollars, mainly in military materiel—remain the most generous of any country outside the Euro-Atlantic, when viewed as a percentage of GDP. Today, members of the Australian Defence Force are in Britain training Ukrainian troops through Operation Interflex. Canberra is also playing a leading role building international cooperation on economic security and resilience against coercion. These are relevant to hybrid threats in domains like cyber where proximity and national or regional boundaries are less significant.

Britain and France also appreciate regional strategic connectivity. They have made similar contributions to Ukraine in monetary terms, although Britain arguably deserves more credit for galvanising allies, as shown recently by the Tallinn Pledge and early announcement of main battle tank transfers. Both countries also seem committed to their Indo-Pacific strategies and the resource commitments they entail. And both are building Indo-Pacific partnerships and interoperability, including the recent signing of a UK–Japan reciprocal access agreement, which follows a similar agreement between Canberra and Tokyo.

Some in Europe are already thinking more ambitiously. The chairman of the UK parliamentary defence select committee, Tobias Ellwood, has called for Britain and France to join a NATO-like arrangement that encompasses a range of Indo-Pacific countries, including all members of the Quad. That’s a bridge too far. It overlooks the historical preference for looser institutions and minilateralism in the Indo-Pacific. The NATO comparison would also play into the hands of Chinese propagandists.

A more subtle and suitable approach would be to build on NATO’s existing engagement with its four Asia–Pacific partners (known as the AP4): Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand. Reflecting concerns about China raised in NATO’s 2022 strategic concept, these links are already growing on a country- and issue-specific basis. The AP4 leaders attended the 2022 NATO summit in Madrid and are expected to be invited again to this year’s summit in July in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius.

Marles and Wong cannot meet NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg while they’re in Europe because—to illustrate the point about regional connectivity—he’s visiting South Korea and Japan this week to discuss topics like emerging and disruptive technologies.

Even so, Marles and Wong could sound out their French and British counterparts about expanding the AP4 into an Indo-Pacific format. Such a format could seek to engage a wider range of countries, notably India. This wouldn’t imply any sort of new collective security arrangement. Rather, an ‘IP5’ could be a platform to discuss key shared concerns, like post-Ukraine approaches to effective deterrence, without obligation or institutional lock-in.

The challenges we face in the era of the China–Russia ‘no limits’ partnership—including Ukraine, Taiwan and borderless hybrid threats—can only be confronted by re-coupling our regions. Marles and Wong should weave that strategic thread through their trip to Europe.