Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Australia-ASEAN relations have transformed since 1974, when Australia became ASEAN’s first dialogue partner. Southeast Asia has become much stronger economically and an increasing number of wealthy countries now compete for ASEAN’s attention. Also, the regional and geopolitical environment has changed radically: the re-emergence of China is the most prominent, but by no means the only, driver of change.

Some in Southeast Asia are asking whether Australia has the capacity to change with the times and move from the anglosphere to Asia? On present evidence, I think not. I believe that fundamentally, Australia will continue to seek security from Asia, and not security in Asia.

There is a fundamental difference in Malaysia’s and Australia’s security philosophies. Malaysia’s philosophy is one that I have called ‘Strategic Embedment’—to integrate ourselves as deeply as possible with as many regional initiatives as possible in order not only to develop close links with partner countries within the region but to achieve maximum strategic space by working with others to influence the regional strategic environment. This philosophy aminates Malaysia’s desire to always be at the heart of ASEAN, including to be involved in sub-regional organisations, strategic partnerships or even initiatives such as the Malaysia–China Community for a Shared Future.

Our philosophy is borne out of the realisation that, as a small country which is a rule-taker, our only hope at rulemaking is to band together with like-minded countries. In the end, of course, we are all alone—but we cannot afford to be.

Australia also aims to achieve maximum strategic space by working with others to influence the regional strategic environment. However, Australia’s preference is to work with countries outside of Asia, especially, again, the anglosphere. This is expressed in Australia’s involvement in AUKUS and the Five Eyes arrangement, as well as in declarations by Australian leaders that Australia is ‘joined at the hip’ with the US and that AUKUS is a ‘forever partnership’. This is not to assert that Australia works with the anglosphere alone to the exclusion of anyone else. That is patently not true: after all, ASEAN–Australia security relations, and the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) are productive, constructive and meaningful. The preponderance of measures to ensure Australian security, however, involve those from outside the region.

Whether this posture is tenable is a matter for Australian evaluation. But allow me to make three points.

First, the strain of isolationism in the US is now very real. It relates to structural challenges within the US itself; mainly, but not confined to, the decimation of its middle class. For our region to be greatly affected would require not an outright victory of the isolationist camp but only the mainstream of the US body politic feeling compelled to respond in a significant way. I am in no way arguing that the US will withdraw entirely from our region, nor do I advocate it. I have always firmly believed that active US involvement here is essential for our socioeconomic progress. However, one can imagine a time when the US and its allies will no longer either undergird or underwrite the international strategic order; after all, that was the situation before the Second World War.

Secondly, the reemergence of China is merely the tip of the iceberg of a much larger phenomenon, which is the Rise of the Rest, or the Global South, when (to quote Nehru) ‘…the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance’. Why has this occurred? Rising incomes is one reason. More importantly, the myth that there is only one, Western model, to achieve socio-economic progress has been broken. China’s rise has proven this. This is not to say that the developing world will adopt the Chinese model; the former is too diverse and the latter too unique. But there are lessons to be learnt, nonetheless. Given the sea change in attitudes in the Global South, those who harp on Western values should stop. If the hole is getting deeper, then stop digging.

This change in strategic outlook is not well understood in the West. This explains why the West has been surprised by the Global South’s subdued reaction to the conflict in Ukraine and its vehemence towards Israel’s genocidal measures in Gaza. If the West is still unable to understand or internalise this phenomenon, all I can do is quote Bette Davis’s line in the 1950 film, ‘All About Eve’: ‘Fasten your seatbelts; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.’

The third point I wish to make concerns ASEAN. ‘Southeast Asia’ is itself a recent concept, a radical reimagining of the region. It is not like Europe, with borders—Ireland in the West and the Urals in the East—long known, and sharing a common history as part of Res Publica Christiana. Today, ASEAN countries are engaged in three distinct, but interrelated historical processes—nation-building; regional integration; and positioning in a fluid, and more competitive, global economic environment.

ASEAN’s challenge is not only to ensure that it is at the centre of the Asia-Pacific’s regional architecture but also to ensure that the ASEAN radius—the range of issues that are relevant to ASEAN and that are brought to and resolved at the ASEAN table—expands as much as possible. ASEAN’s centrality is not yet in the natural order of things. The radius is not as large as some imagine.

I believe that it is in the context of strengthening ASEAN centrality—in expanding the radius—that both our countries have an important role to play in paving the way for regional geostrategic resilience—Malaysia as a founding member of ASEAN and chair in 2025, and Australia as ASEAN’s first dialogue partner.

Australia is joining the US and Japan in developing systems for shielding territory from air and missile attack. The news comes as the Department of Defence and Royal Australian Air Force are under pressure to move faster in implementing such a capability.

‘Today, we announce our vision to cooperate on a networked air defence architecture among the United States, Japan and Australia to counter growing air and missile threats,’ Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and President Joe Biden said in a joint statement this month as Fumio visited Washington.

They also noted that Japan may be able to participate in advanced projects under Pillar 2 of the AUKUS security pact between Australia, Britain and the United States, and that the US, Japan and Australia could collaborate on autonomous air systems, particularly collaborative combat aircraft. Finally, at a US-Japan bilateral level, the statement highlighted joint development of the Glide Phase Interceptor to counter high-end, regional hypersonic threats.

There’s a lot in there for Australia to think about as it moves towards releasing its 2024 National Defence Strategy and an accompanying update to the Integrated Investment Program (IIP). The first thing to think about is integrated air and missile defence (IAMD).

In an earlier article I argued that Australia had fallen behind in IAMD. Last year’s Defence Strategic Review identified the capability gap, noting that a layered IAMD system—comprising a battle management system, command and control network, sensors and interceptor batteries—must be delivered urgently. ‘Defence must reprioritise the delivery of a layered IAMD capability, allocating sufficient resources to the Chief of Air Force to deliver initial capability in a timely way and subsequently further develop the mature capability,’ it said.

Now, the announcement for a US-Japan-Australia partnership will hopefully encourage Defence and the government to prioritise IAMD in the IIP. If Australia is to pursue capabilities for its strategy of deterrence by denial, it must focus on more than strike and power projection. We must hold a shield as well as a sword.

We saw an IAMD system impressively in action on 14 April, when the one wielded by Israel, supported by US, British and French forces, decisively defeated an Iranian attack by long-range drones, cruise missiles and ballistic missiles. Had Israel lacked such a capability, it might have suffered high casualties and extensive damage. Australia should learn the lesson and act quickly.

Australian efforts to develop IAMD capability have dragged on. Lockheed Martin is leading the development of project AIR 6500 Phase 1 which is a joint air battle management system that will sit at the centre of the eventual IAMD capability. It’s a good first step, but the IAMD system must be deployed quickly, rather than be delayed by unnecessarily high performance objectives. The emphasis must be on minimum viable capability, not one perfect system to rule them all (eventually, at enormous cost). That message was in the DSR.

If Australia’s strategic outlook were not rapidly deteriorating, a more leisurely approach to developing IAMD could be justified. But we lack time, with assessments that China could attempt to seize Taiwan as early as the second half of this decade and prompt conflict with the United States.

The quickest and safest path to deploying an operational IAMD capability is by military–off–the–shelf (MOTS) acquisition of the battle management system, command and control network and interceptor batteries. Australia could simply buy a range of systems now available and operationally proven, such as Lockheed Martin’s MIM-104 Patriot and longer-range THAAD. Alternatively, we could improve the short-range NASAMS system that Norway’s Kongsberg is delivering for the army. It uses AMRAAM interceptors but can accept integration of other, farther-flying munitions, such as the AMRAAM-ER with a range of 70km and Raytheon’s SkyCeptor with a range of 200km.

So Australia has a range of MOTS options to choose from. AIR 6500 could progressively evolve from an initial array of MOTS systems, providing a stronger IAMD capability later. Those advances would be important, particularly as the Chinese Rocket Force gains in sophistication.

They could be quickly introduced as part of the trilateral US-Japan-Australia IAMD effort. Japanese cooperation with AUKUS Pillar 2, particularly any that addresses hypersonic threats, might also contribute to bolstering Australian IAMD capability.

Hypersonic threats and the risk of increasingly sophisticated long-range missiles adaptable to both nuclear and conventional attack should also present a requirement for the US, Japan and Australia to work together to counter strategic risks as part of an effort to strengthen US extended nuclear deterrence.

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) is very clear: Australia must change the way it plans for and acquires defence capabilities. The DSR recognises that doing so will require a net assessment to examine the various factors that may contribute to or detract from the country’s military capabilities.

A previous ‘balanced force’ approach optimised to a broad set of contingencies is no longer suitable, given the strategic circumstances. Rather, the DSR recommends that Australia’s approach to defence planning focus on ‘building force structure, force posture and accelerating preparedness … to ensure it is focused on the levels of risk in our current strategic circumstances’. It adds that this ‘much more focused force structure [is] based on net assessment, a strategy of denial, the risks inherent in the different levels of conflict, and realistic scenarios agreed to by the Government.’

Since the publication of the DSR, little information on how Australia will undertake a net assessment has been released. Given that it is significantly different from Australia’s traditional approach to force structure development, encompassing elements of security that extend beyond defence and requiring significant financial and human resources, it’s worthwhile discussing how this might manifest in the Australian context.

Typically, the absence of a specific threat has meant that Australia’s defence planning framework, like those of many of its allies, has been based on capability planning. In the post-Cold War era, with no specific or significant security threat, such a risk-based approach provided strategic flexibility. Capability planning, in theory, ‘advocates developing a whole range of capabilities from peacekeeping, counterinsurgency, precision strikes, to full-scale war that might be required’. As the future adversary, area of operation and type of conflict were uncertain and, potentially, unknowable, such a risk-based hedging strategy made sense.

But changing times necessitate a new approach. This is where net assessment comes to the fore. It’s defined as ‘a conceptual approach to understanding the critical features characterizing long-term competitive relations among strategic actors’. John Blaxland notes that it provides ‘a holistic, comprehensive analysis of long-term and broad-ranging dynamics to derive a multinational and multispectral net assessment of the security challenges faced in the medium term (out 5–10 years) and long term (spanning the next generation, out to 2040 and beyond).’

Andrew Shearer, the director-General at the Office of National Intelligence, suggests that ‘net assessments work well because of their ability to take a wider aperture … [as they go] to the different dimensions of power, not only military, but economic, diplomatic and soft power’, all of which are key to the DSR’s whole-of-government national defence strategy. More holistic and powerful than a typical threat assessment, a net assessment ‘accounts for and forecasts the strategic interaction that would occur in any conflict’, furnishing decision-makers with a strong foundation for making informed choices about future force structure.

Fundamentally, net assessment is built around three considerations. First, it details the relative balance between two protagonists across the full spectrum of power dynamics, situating them within domains of contestation. Second, by identifying pockets of imbalance, it captures potential asymmetries between protagonists that are open to exploitation, thus identifying both opportunities and threats. Finally, it recognises the dynamic nature of competition. Over time, as conditions change, so does the relative balance. Therefore, asymmetries will be fleeting.

To date, net assessment has been the tool of major powers—the US and USSR/Russia—and more recently NATO and the UK. The net assessment that Australia employs must be adapted to Australia’s middle-power status and its strategic location, as those are critical in establishing in what form and under what circumstances Australia can realise its strategic goal of deterrence by denial.

Establishing a net assessment capability from scratch is a significant undertaking, something that might not be evident from the DSR. Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith’s 2021 report Deterrence through denial: a strategy for an era of reduced warning time provides a prescription from which to build a bespoke Australianised net assessment approach. They acknowledge that shifting to net assessment is challenging, since ‘the task of appraising potential enemies in forming net assessments is growing ever more complex and more difficult as the range of threats is becoming more elusive.’ Capacity will constrain what Australia can realistically achieve, as net assessment requires a long-term commitment of significant resources, both financial and human. Because Australia’s intelligence and analysis community is relatively small, at least in comparison with those of other nations that perform net assessments, ambitions will have to be managed. While the assessment must remain sovereign, data sharing between allies will allow Australia to overcome some of the resourcing challenges that net assessment creates.

While it is not obvious to the analytical community, one would expect that Defence has commenced the process for establishing a net assessment capability. However, there are some key facets that it will need to address, beginning with defining the terms of reference that will guide the assessment. In addition, understanding balance and asymmetric advantage over time requires knowledge, expertise and analytical models. Building those bespoke systems to perform the assessment requires an upfront investment and long-term dedicated resources. And Australia must empower those delivering the net assessment function so that they can access the data they need unimpeded and provide impartial advice to government. That independence has been critical to the success of the Office of Net Assessment in the US.

Originally published on 9 August 2023.

In the latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs, the Lowy Institute’s Sam Roggeveen makes assertions about the priorities of China’s nuclear targeting of Australia, as well as what he claims will be Australia’s missile targeting of Chinese territory. I consider much of what he has written to be wrong.

In ‘Target Australia: Is the alliance making us less safe?’, Roggeveen asserts that the basing of US B-52 bombers at the Tindal airbase near Darwin will make the site a priority nuclear target of China because the bombers could strike China’s nuclear missile silos and bases, early warning radars and nuclear command and control facilities. But the distance from Tindal to military targets in the south of mainland China is over 4,500 kilometres and the B-52’s operational speed is subsonic (900 km/h). This means that it would take in the order of five hours to reach key military targets in China’s south. And flying from Tindal to Beijing would take more like eight hours, providing China with plenty of warning.

In contrast, the joint US–Australia intelligence facility at Pine Gap near Alice Springs will be by far China’s most important and time-urgent nuclear target because of its ability to give the US instant, real-time warning of a Chinese nuclear attack, the precise number of missiles, their trajectory and their likely targets. There’s nothing novel about Pine Gap being identified by potential nuclear adversaries as a priority target. In the late 1970s, it was made quite clear to me during talks in Moscow that Pine Gap was a priority Soviet nuclear target. And in 2016, I was warned: ‘In the event of nuclear war between Russia and America, you Australians will find that nuclear missiles fly in every direction.’

The fact is that the KGB had detailed evidence in the late 1970s from two US spies, Andrew Lee and Christopher Boyce, with access to the Pine Gap ‘intelligence take’ of its key role—together with the joint facility at Nurrungar near Woomera—in detecting and tracking Soviet ballistic missiles and listening to the USSR’s military communications. We can assume that the Russians will have briefed China about Pine Gap, which now includes the space-based infrared detection capabilities of the old Nurrungar base, being a much more time-urgent target than Tindal. Roggeveen asserts that China would not strike Pine Gap because of its important role in US nuclear deterrence. That is not my view: we’re not talking about deterrence and nuclear arms control here but a decision by China to use nuclear weapons. Tindal would not be targeted with the urgency that Roggeveen claims.

Roggeveen asserts that Australia’s acquisition of Tomahawk cruise missiles ‘can be interpreted only one way: Australia wants the capability to strike targets on Chinese soil’. I don’t know how Roggeveen’s imagination jumped to this conclusion. But the 2023 defence strategic review recommends that Australia’s concept of defence have ‘a focus on deterrence through denial, including the ability to hold any adversary at risk’. That does not include striking China’s territory, which would be a dangerous gamble by Australia. But attacking China’s military bases in the South China Sea and contingently in the South Pacific certainly should be included in our future targeting doctrine if—as Roggeveen accepts—there’s a likelihood of a ‘Chinese military assault on Australia’.

Deterrence theory holds two alternatives: deterrence by punishment and deterrence by denial. Deterrence by punishment gives priority to destroying the enemy’s territory, military bases and key population centres. By comparison, deterrence by denial requires Australia to hold potential adversaries’ forces and forward-based military structure at risk from a greater distance rather than waiting for them to operate in a threatening way in our immediate approaches.

My colleague and a former deputy secretary of Defence, Richard Brabin-Smith, and I wrote an ASPI report in 2021 titled Deterrence through denial: a strategy for an era of reduced warning time. We argued that Australia needed to acquire highly accurate, long-range missiles. In this way, we could deter military actions against Australia’s interests with less dependency on warning time than in the past. Holding a potential adversary’s forces at risk from a greater distance would influence the calculus of enemy costs involved in threatening Australian interests directly. For this we need to acquire long-range anti-ship strike missiles, cyber capabilities and area-denial systems.

Any credible future enemy operating directly against us will have highly vulnerable lines of logistics support back to its home base in North Asia. The closer it comes to our strategic approaches the more vulnerable its logistic support will become. If a potential adversary such as China develops—as it already has—several military bases in the South China Sea (or in the South Pacific in future), Australia must be able to destroy them if necessary.

Nowhere in the defence strategic review or in our own writings is there a suggestion that Australia needs to be able to strike mainland China. Attempting such deterrence by punishment would be extremely provocative and dangerous given China’s military capabilities. And no commentator in their right mind would suggest such a high-risk defence policy. The idea of being able to inflict unacceptable punishment on China is not within the realms of credible Australian defence policy.

There are further sweeping assertions by Roggeveen that the AUKUS relationship will increase the likelihood that Australia will be locked automatically into fighting alongside the US should Beijing go to war over Taiwan ‘or for another reason’. It will, of course, be important that we assert our absolute sovereignty over the missions to which we commit our future nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs). When Britain decided to buy US Trident missiles for its ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), London made clear that it would not be subordinate to Washington’s nuclear targeting priorities. Washington confirmed the UK’s sovereignty in formal writing to the British government in this vital regard.

If a future Australian government agrees, our Virginia-class SSNs will be able to use 2000-kilometre-range anti-ship missiles to strike China’s forces in the Taiwan Strait. That could be done from the safety of deepwater trenches east of the Philippines without detection.

As to other roles for our SSNs in a Taiwan contingency, we should consider discussing with Washington our capacity to deny the narrow straits of Southeast Asia to China’s overseas trade (it imports 80% of its oil through the Malacca Strait). That would be an important, independent military role for Australia, but without the potentially high cost of losing our relatively small number of military assets in a direct war over Taiwan.

Roggeveen is correct when he states that the US would be unlikely to subordinate nuclear-related missions to Australia’s submarine fleet. Even so, he observes that Australian SSNs might encounter Chinese SSBNs during future operations. In the Cold War, we regularly operated against the Soviet Navy in close-quarter operations that were greatly valued by Washington. UK SSNs trailed Soviet SSBNs for prolonged periods at distances as close as 500 metres and practised what was coyly termed contingency ‘target acquisitions’. In any such future occurrences, we would need ironclad rules of engagement reflecting our national sovereignty targeting priorities.

However, the main problem with Roggeveen’s article is that he focuses entirely on the dangers of resisting and deterring China without comparing that approach with the dangers of not resisting and not deterring China. That is not a prudent approach to making Australia’s security policy.

Roggeveen concludes that it’s not in Australia’s strategic interests to be drawn into a war over Taiwan. But neither is it in our interests to see a US defeat in such a war precipitating the acquisition of nuclear weapons by, say, Japan and South Korea. And neither is it in our interests to see Taiwan’s vibrant democracy crushed by the brutal military occupation of the People’s Liberation Army. There should be no place for such value-free judgements in the formulation of Australia’s defence policy.

As we lament the state of Australia’s capability to engage with Asia, we should pay heed to one indispensable means of acquiring it: good, factual news reporting on our region, easily accessible to any interested reader.

It’s perplexing to observe that as Asia inexorably grows more vital to our prosperity and security, the resources invested in the task of publicly recording its affairs has visibly declined.

News bureaus have closed, the once bustling corridors of buildings that housed foreign media are quiet, the ghosts of newsmen and women past hover over empty bar stools at foreign correspondents’ clubs; worse, big stories are covered at a distance as larger swathes of the region are left to fewer and fewer reporters and click-bait triviality jostles for space online with stories that matter.

A reminder of the need to invest more in our coverage of the region—and how thin the coverage and capability have become in both the ‘legacy’ media and its newer online manifestations—was the passing on 7 December of the great New Zealand–born foreign correspondent John McBeth.

McBeth dedicated his life to reporting Asia. His journey ought to be an inspiration for another generation of correspondents (and, more importantly, readers) to pursue the richness, the drama, the fascination and, of course, the great significance of the Asian story.

McBeth arrived in the early 1970s in a Thailand that, along with its Southeast Asian neighbours, was in the first stages of a journey to become one of Asia’s economic powerhouses, juggling the geopolitical vagaries of the Cold War and facing the societal challenges that come with adjusting to modernity. Asia would be home for the rest of his life.

In Bangkok, he found work on a string of wire services and publications before settling at the Far Eastern Economic Review, then the pre-eminent publication covering the region’s political and business affairs.

In those years, Bangkok was the natural base for a thriving international media corps documenting the disaster bequeathed to Indochina by the wars fought by the French and Americans in Vietnam, manifested especially in the terror next door in Cambodia. McBeth was among the first to tell the scarcely believable stories of Khmer Rouge atrocities, journeying to border camps to listen to refugee accounts of death and survival.

Thailand offered its own slate of crimes to record. There was the macabre trail of 14 bodies left by the notorious serial killer Charles Sobhraj. And political crimes too in the string of coups and attempted coups—McBeth’s close friend, the Australian cameraman Neil Davis, was killed in one in Bangkok in September 1985.

Posted by the Review to South Korea, McBeth was witness to the rise of democracy and the fierce tear-gas-saturated street battles between students and the security forces of Chun Doo-hwan. He went on to cover the mercurial Philippines scene following the end of the 21-year rule of Ferdinand Marcos.

This regional odyssey—coinciding with the post-war leap in Asian development and stop-start democratisation—finally took him to Indonesia to observe the last brazen years of Suharto’s New Order. The end of Suharto was foretold in the stories of freebooting, often linked to the first family, like the world’s biggest gold find, Busang in the jungles of East Kalimantan, that turned out to be pure fiction. Through the downfall of Suharto and beyond, McBeth stayed the course in documenting Indonesia during its political and economic transformation over a period of three decades.

In all his years living in Asia, he never stopped interviewing, observing and writing, save a few months when he was recuperating from the loss of a leg put down to smoking (a habit he promptly discarded). Even after the traumatic amputation, he was anxious to pick up a notebook and fretted the bosses might not let him do it. He even offered to take a pay cut to get back in the field. He would say happiness for him—or at least a sense of purpose—came with knowing he had a story to work on in the morning.

McBeth had the ebullient persona of the correspondent of his era. Over lunch, he could be a humorous storyteller and acerbic critic of the business he was in, but he also exhibited humility about the craft and his own contribution. His memoir was deliberately titled Reporter: fifty years of covering Asia. He eschewed the grander label ‘correspondent’, and he didn’t covet awards or tailor his reporting to suit the taste of award judges.

Most importantly, he tried to tell it as it was. He wasn’t a crusader. He acquired an eye for a good story. He dug into the facts, checked them, then wrote what he found. And he was fair.

That could mean going against the tide. Before the 2019 presidential elections in Indonesia, he wrote in the Asia Times: ‘Facilitated by a largely unquestioning media, Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s government has become a master at the game of smoke and mirrors, which in simplistic form is all about convincing the public that things are happening when they really aren’t.’

But when those words unleashed a wave of hate from the Widodo legions online, the president’s own consigliere, Luhut Pandjaitan, came to McBeth’s defence.

This points to other ingredients of success: the patient building of contact networks—something fly-in, fly-out correspondents don’t do; an unswerving commitment to the story and living it; and the value of having a reputation for practising fairness. It was no accident that many an Australian ambassador sought McBeth’s insights.

In an era when opinion and supposition abound on paper and online, these look like forgotten or dying virtues. Even the newswires are given over to more opinion and commentary to compete with the cacophony of conjecture on the likes of X.

For Australia—indeed for the English-language media broadly—more troubling is the general retreat in on-the-ground news coverage of the region when our need to know has rarely been greater. Venerable publications based in the region like the Review and Asiaweek shut their doors long ago. Among the Australian media, only the ABC retains a large network of full-time correspondents, and it is yet to return a correspondent to the People’s Republic of China. More Australian media resources are spent on North America and Europe.

McBeth was in a line of great correspondents to venture to Asia in the 1960s and 1970s for whose dedication readers can be enduringly grateful. They included two fellow New Zealanders, Peter Arnett, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting of the Vietnam War (and who is sometimes described as ‘the world’s greatest war correspondent’), and the late Kate Webb, intrepid and indefatigable, who experienced the novelty of reading her own obituary after being presumed dead in Cambodia when in fact she had been captured by Viet Cong forces who protected her from the Khmer Rouge.

Arnett once described Kiwis as ‘born risk-takers’, and that is true of this remarkable trio. We need to revive that spirit of adventure. We need the commitment to the story it implied. But, more than that, we need investment in the reporting necessary to understand our dynamic region.

During the recent pro-Palestine and pro-Israel protests in Sydney and Melbourne, many Australians have demanded an end to the conflict in Gaza, lawfully exercising their freedom of speech. A small number of protestors, however, have behaved in a way that is incompatible with Australian values and laws. Traditional media and social media understandably highlight extreme behaviour at protests and the growing cost of security. We, the authors, condemn violent behaviour and racist abuse, but not the protests.

News outlets and social media continue to bring the world a front-row view of the unspeakable horrors of the Israeli–Hamas conflict. This imagery is often disseminated to evoke shock and emotion. Beyond Gaza and Israel, the war has brought to the forefront deeply divisive sentiment, which has included legal democratic expression but also racial vilification, hate speech and even violence.

There’s no room in Australia for political and ideologically motivated violence. It’s not easy for Australia’s law enforcement and intelligence agencies, which must be clear-eyed about immediately dealing with these issues while treading a careful path to safeguard the right to free speech and thought that is crucial to the health of our democracy.

Australia is a diverse nation with equally diverse opinions and perspectives regarding the conflict.

For many in the Palestinian and Israeli diasporas, this war has a profoundly personal dimension. These communities are directly connected through friends and family caught up in the war. Even people without a personal link, including those from Australia’s Jewish, Muslim and Arab communities more broadly, feel connected to the conflict.

Over several weeks, citizens of open democratic societies globally have exercised their right to publicly express their views on the war.

Outside the Arab world, protests have occurred in major cities across Europe and the United States. In Australia, citizens have vocally expressed their sentiments with pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli demonstrations in major cities. If protestors cross the line to hate speech, law enforcement agencies should pursue those who’ve committed criminal offences. However, the demonstrations have mostly allowed those involved to express their perspectives and frustrations publicly.

A key element in preventing terrorism is ensuring freedom of expression. Australians have divergent views on the war and some disagree with the government’s stance. That’s okay because Australia is a democratic nation. It would be wrong to ignore these differences. But it would be equally wrong to over-securitise how we deal with legitimate and legal expression of thought.

Since 2001, Australia has listed Hamas, in its entirety, as a terrorist entity for financial sanctions under Part 4 of the Charter of the United Nations Act 1045 in implementing UN Security Council resolution 1373. This listing doesn’t mean Australians can’t protest against the Gaza conflict. It doesn’t prevent Australians from debating whether Israel’s actions in Gaza are proportionate. Nor does it prevent Australians from expressing support for Israel and Israeli victims of the Hamas attacks.

Preventing anti-Semitism and preserving public safety have been used to justify the anti-Palestinian decisions of various governments. In some cases, these decisions have worsened social tensions, especially between Jewish and Muslim communities.

In Europe, several countries have banned pro-Palestinian protests and slogans. Even before the beginning of the Israel–Hamas war on 7 October, Germany had restricted pro-Palestinian demonstrations. Since then, education authorities in Berlin have told schools that they could ban students from wearing the Palestinian Kufiya scarf and ‘free Palestine’ stickers.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has also used the recent surge of anti-Semitism in Germany as an excuse to harden the country’s immigration policies. In an interview, he stated: ‘We must finally deport on a large scale those who have no right to stay in Germany.’

In France, local authorities are banning pro-Palestine protests on a case-by-case basis.

Policies like this risk undermining the democratic right to peaceful assembly and freedom of speech. At such times, freedom of expression, free from hate speech and vilification, serves as a pressure valve for communities.

To increase social cohesion amid the ongoing horrors of the Israel–Hamas war, Australian state, territory and federal governments must do more to show that they stand in solidarity with the victims on both sides of the conflict, as well as the Israeli, Palestinian, Jewish and Muslim communities more broadly. It must provide citizens with opportunities to express their political perspectives on the war as long as that’s done in accordance with Australian laws.

For example, if an Australian jurisdiction supports a group establishing a condolence book for the victims of the 7 October attacks, it should also support a group with a condolence book for the war’s non-combatant victims. If a pro-Israeli demonstration is allowed to go ahead, so too should an anti-war demonstration.

Australian democracy ensures that people can act, speak and think freely, as long as that doesn’t stop others from doing the same. It also provides for equality before the law. And it ensures that communities are safe and secure and that governments are transparent, responsive and accountable. The Australian government makes foreign policy decisions, and universal suffrage ensures that it’s answerable to the electorate.

While there’s no end in sight to the turmoil of the Israel–Hamas war, what can be controlled is governments’ responses on the domestic front. The peaceful exercise of freedom of speech in democratic countries, including Australia, is needed more than ever during this polarising conflict. Rather than deciding which side is right or wrong, the opinions and viewpoints of all citizens, whether pro-Israel or pro-Palestine, must be respected.

In April, the US Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) proposed a rule relating to the ‘new clean vehicle credit’ under the Inflation Reduction Act. The proposal would provide a tax credit of up to US$3,750 for American taxpayers who purchase an electric vehicle (EV) if a certain percentage of the value of the EV battery’s critical minerals are extracted or processed in the US, free-trade agreement countries (such as Australia) or countries with which the US has critical-mineral agreements (such as Japan).

However, the rule would disqualify EV purchasers from receiving both the US$3,750 critical-minerals tax credit and the US$3,750 battery-components tax credit if ‘any of the applicable critical minerals contained in the battery … were extracted, processed, or recycled by a foreign entity of concern [FEOC]’.

While the Treasury and the IRS have said they will issue ‘subsequent guidance’ on the definition of FEOC, if they adopt the Department of Commerce’s definition for the CHIPS and Science Act, it would include any entity with at least 25% ownership by an FEOC. Under current US law, FEOCs include companies ‘owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a government of a covered nation’, which includes China, Russia, Iran and North Korea.

Ostensibly, if batteries assembled in the US use lithium extracted in Australia but processed in China, that lithium would be considered processed by an FEOC, disqualifying EVs that use those batteries from both the critical-minerals tax credit and the battery-components tax credit.

Given the lack of clarity in the Treasury’s interim guidance as well as the lack of a final rule, opinions differ on whether the Treasury and IRS will adopt Commerce’s FEOC definition. The law firm Hogan Lovells believes ‘there is a good chance that Treasury will follow Commerce’s CHIPS Rule’ because ‘it would be strange for the two agencies to issue conflicting definitions’. Conversely, the law firm Covington & Burling writes, ‘While there is a good reason to adopt a single interpretation for the same term in nearly concurrently-enacted statutes, Treasury is not bound to apply the CHIPS Act interpretation of “foreign entity of concern”’ to the Inflation Reduction Act. Nonetheless, the US government seems likely to adopt a uniform FEOC definition across government entities.

Consequently, EV companies selling in the US market will likely avoid sourcing minerals from—and investing in—Australian mineral projects with Chinese ownership. For example, Australia’s Greenbushes lithium mine would likely be deemed an FEOC since the Chinese company Tianqi holds 26% ownership, disqualifying any EV batteries that source Greenbushes lithium from Inflation Reduction Act tax credits.

American EV companies may also purchase less Australian-mined materials and invest less in Australian mines because Australian mining companies often rely on Chinese refineries. Since Australia lacks substantial refining capacity, it ships many of its minerals to China for processing—for instance, 90% of all lithium produced in Australia is refined in China. Under the proposed rule, EVs with batteries containing Australian-mined, Chinese-refined minerals would be ineligible for the EV tax credits.

If Australia wants companies that sell EVs in the US to source Australian-produced minerals and invest in Australian mineral projects, the Australian government could provide grants and loans to Australian companies for processing minerals into battery materials like nickel sulfate and cobalt sulfate, as well as precursor cathode active material and cathode active material. At the Darwin Dialogue in April, Resources Minister Madeleine King noted, ‘We can build on our advantages, countering national and regional supply risks by building our processing capabilities and moving up the value chain.’ Indeed, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese recently announced a $2 billion expansion in the Critical Minerals Facility, bringing the total financing available for Australian critical-mineral projects—including processing facilities—to $6 billion.

Australian mining companies could also seek to partner in processing projects in the US, other free-trade-agreement countries, and critical-mineral agreement countries, enabling Australian-mined critical minerals to qualify for the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credits. Alternatively, Australia could seek to decrease Chinese ownership by requiring Chinese divestment from Australian critical-mineral companies and projects. To prevent further Chinese investment, Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board could more tightly screen investments in the minerals sector too.

Nonetheless, without further updates from the Treasury and IRS—which are expected by the end of the year—Australian companies can’t fully understand how to comply with the Inflation Reduction Act’s FEOC definition. Moreover, US Senator Joe Manchin, a vocal critic of the proposed rule, said he will support suing the Biden administration once the final rule is released. Thus, the final FEOC definition could change and, consequently, its implications for Australia.

In an ASPI report released today, we argue that geopolitical challenges, notably Beijing’s growing power and coercive behaviour, justify a greater effort to elevate and sustain the important relationship between Australia and South Korea.

Changes led by President Yoon Suk-yeol, who aspires to make South Korea a ‘global pivotal state’, challenge the view that Seoul lacks the bandwidth to tackle security beyond the Korean peninsula. Initiatives like the South Korea–US–Japan trilateral launched by the three leaders at Camp David in August show that Seoul is willing to take steps to strengthen its security partnerships even if that risks upsetting Beijing.

Australia is also looking to achieve more with South Korea, overcoming years of underperformance and inconsistency in bilateral relations. Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles told an audience in Seoul last week, ‘As mature liberal democracies, I’m convinced the strategic defence relationship between Australia and South Korea can go from strength to strength and is full of opportunities to deepen it even further. I’m visiting here for the second time in a year to act on that conviction.’ It’s a shame that the response to Hamas’s attacks against Israel prevented Foreign Minister Penny Wong from joining Marles in Seoul last week, but hopefully the annual Australia–South Korea 2+2 foreign and defence ministers’ meeting can take place later this year.

Our report makes six recommendations to boost collaboration between Australia and South Korea, both bilaterally and with a wider set of regional partners. These recommendations span the three pillars of 2021 Australia–Republic of Korea Comprehensive Strategic Partnership: strategic and security cooperation; economic, innovation and technology cooperation; and people-to-people links.

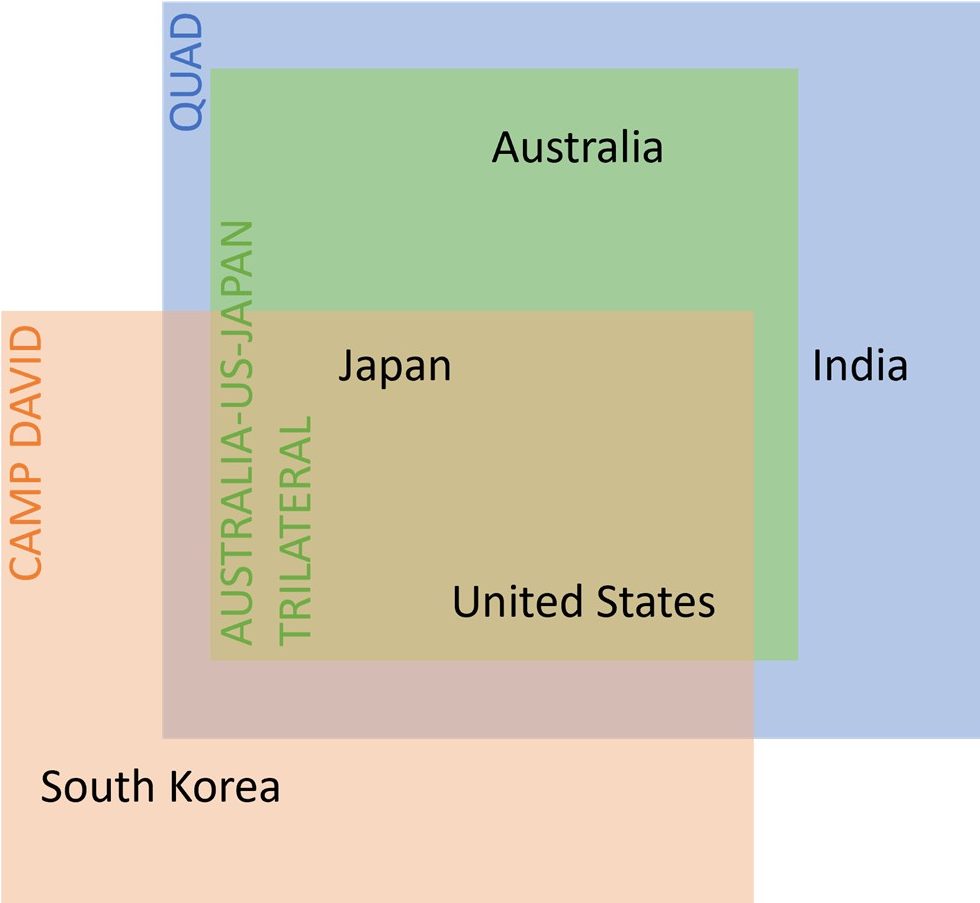

Under the strategic and security pillar, Australia and South Korea should explore ways to incrementally knit together the longstanding Australia–US–Japan trilateral, which includes the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue between foreign ministers and the Trilateral Defence Ministers’ Meeting, with the nascent Camp David trilateral (see Figure 1). This process mustn’t be rushed and should start with engagement between officials rather than ministers. One option would be to invite Australia as a guest to the annual Trilateral Indo-Pacific Dialogue, a senior-official-level meeting for coordinating implementation of national Indo-Pacific strategies, especially as they apply to Southeast Asia and the Pacific island countries.

Figure 1: South Korea’s and Australia’s engagement in major regional minilaterals

As well as increasing military interoperability and joint exercises, defence industry collaborations like Hanwha Defence’s armoured vehicle centre of excellence in Geelong should be supported by Australia’s forthcoming defence industry development strategy, which requires a broad definition of sovereign capability focused on the resilience of supply rather than Australian ownership.

Cooperation under the economic, innovation and technology pillar of the partnership is key to countering Chinese coercion, which Australia and South Korea have both experienced. Both countries have responded to coercion by diversifying their trade relationships and improving supply-chain resilience in sectors like critical minerals and technologies. In this context, Australia and South Korea should support collaboration relevant to the advanced capabilities stream of the AUKUS agreement, focusing on defence-relevant technologies in which both countries are among the leaders in publishing high-impact research (see Table 1).

Table 1: Defence-relevant technologies on which Australia and South Korea should collaboratea

| Defence-relevant technologies | Proportion of high-impact research output (%) | Technology monopoly riskb | ||||

| China | Second leading country | South Korea | Australia | South Korea and Australia | ||

| Sonar and acoustic sensors | 49.4 | 12.5 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 4.4 | High |

| Electronic warfare | 46.0 | 14.4 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 5.9 | High |

| Novel metamaterials | 45.6 | 16.9 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | Medium |

| Directed-energy technologies | 39.1 | 19.1 | 5.9 | 1.9 | 7.8 | Medium |

| Machine learning | 33.2 | 17.9 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 6.0 | Low |

| Adversarial AI | 30.9 | 25.2 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 8.4 | Low |

| Protective cybersecurity technologies | 22.3 | 16.8 | 2.7 | 5.7 | 8.4 | Low |

| Autonomous systems operation technology | 26.2 | 21.0 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 6.8 | Low |

| Advanced robotics | 27.9 | 24.6 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 6.6 | Low |

Notes:

a. The technologies in this table were chosen because they are listed as defence-relevant technologies in ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker. However, only the technologies that fulfilled the following two criteria were chosen: China ranked first in terms of proportion of high-impact research, and South Korea and Australia ranked in the top 10 countries in terms of proportion of high-impact research output.

b. The technology monopoly risk metric seeks to highlight concentrations of technological expertise in a single country. It incorporates two factors: how far ahead the leading country (in this case, China) is relative to the next closest competitor, and how many of the world’s top 10 research institutions are located in the leading country (China). This metric, based on top 10% research output, is intended as a leading indicator for potential future dominance in technology capability (such as military and intelligence capability).

Source: Critical Technology Tracker, ASPI, 2023.

Canberra and Seoul could also do more to capitalise on their complementary strengths in space technologies, including small satellites. South Korea launched its first commercial-grade satellite in May 2023 and ranks highly in satellite-related research according to ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker. Northern Australia’s advantageous geography makes it the perfect location for cooperation on space launches and co-development of small satellite technologies with applications such as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; missile early warning; and communications.

Drawing back the lens to capture wider priorities, the two countries should play a leadership role in the Indo-Pacific region’s clean-energy transition, including through technical and development assistance focused on green hydrogen. This would also help address South Korea’s reliance on Australian coal and gas, and assist both countries meet their 2050 net-zero-emissions targets. By working together, they could support the development of regional supply chains for critical minerals used in clean-energy technologies, such as lithium, further improving resilience to Chinese coercion.

The people-to-people pillar of the partnership probably receives the least government attention, but it is vital and evolving rapidly. South Korea’s soft-power ascendancy includes the attraction of Hallyu (the ‘Korean wave’) to many Australians, which has driven interest in South Korea and the expansion of Korean studies in Australia. South Korea was the third most popular destination for Australians participating in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s New Colombo Plan program in 2023. In contrast, Yonsei University is the only South Korean university to host an Australian studies centre. DFAT could craft an ‘Australia now’ campaign that engages Korean Australians who are famous or leaders in their field, including in the K-pop industry, as cultural ambassadors to address the imbalance and promote interest in Australia among the South Korean public.

The convergence of Australian and South Korean strategic interests on the challenge posed by China underpins recent progress in the bilateral relationship and lays the foundations to go further. The right investments now could help insulate this crucial strategic partnership from the risk of backsliding if there’s a change in the political wind—an approach that sounds familiar as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visits Washington.

In this episode, ASPI’s Gatra Priyandita speaks to Thomas Parks from the Asia Foundation about geopolitics in Southeast Asia. While there’s a lot of attention on the US–China rivalry and its implications for the region, Gatra and Tom focus on the different regional dynamics in Southeast Asia, including ASEAN, regional challenges and the relationships that countries like Australia and Japan have in the region and how they have changed.

Zooming in on Indonesia, Gatra speaks to Natalie Sambhi, executive director of Verve Research, about Indonesian politics and foreign policy and Australia’s relationship with Indonesia. They discuss Indonesia’s vision for the world and how it aligns with Australia’s, the roles both countries can play in shaping international rules and norms, and how to further strengthen the bilateral relationship, including through education.

It has been 56 years since the last person was executed in Australia and almost 40 years since the last death sentence was given by an Australian court. The death penalty has been abolished in every Australian jurisdiction, and the federal parliament passed legislation in 2010 to ensure that it can’t be reintroduced anywhere in Australia.

Given this, does the fact that today, 10 October 2023, is the 21st World Day Against the Death Penalty have any continuing relevance for Australia?

We would suggest that it does, for two key reasons.

The first is that the universal abolition of the death penalty continues to be a key human rights issue, and Australia’s continued global leadership is strategically important.

Australia’s opposition to the death penalty has become an express part of our global human rights advocacy. Australia’s strategy for abolition of the death penalty, released in 2018, reaffirms that Australia ‘opposes the death penalty in all circumstances for all people’ and commits Australia to pursuing the universal abolition of the death penalty.

The reality is that the use of the death penalty has been increasing. Amnesty International recently reported that recorded executions reached a five-year high globally in 2022, with 883 people known to have been executed across 20 countries. That number reflects only confirmed judicial uses of the death penalty, and the actual number of executions is likely to be significantly higher.

At the end of 2022, an estimated 28,282 people around the world were facing death sentences. Fifty-five countries still use the death penalty, with the highest numbers of known executions in 2022 taking place in China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the United States.

We should be particularly concerned about the way that the death penalty is being both imposed and carried out. For example, one year after the death in custody of Iranian woman Mahsa Amini, Iranian authorities have reportedly imposed death sentences on at least 26 individuals in connection with the subsequent protests and seven individuals have been executed. They included Mohammad Mehdi Karami, a 22-year-old karate champion, who was executed after reportedly being given less than 15 minutes to defend himself in court.

The UN Human Rights Commission’s fact-finding mission on Iran has suggested that these penalties ‘are being imposed following legal proceedings that lack transparency and fail to meet basic fair trial and due process guarantees under international human rights law’.

In the US, the Death Penalty Information Center labelled 2022 ‘“the year of the botched execution” because of the high number of states with failed or bungled executions’. A shortage of lethal-injection drugs led Idaho to pass a law in March this year restoring the use of firing squads in executions. In August, the Alabama attorney-general confirmed that the state intended to carry out an execution using nitrogen hypoxia. This method kills the prisoner by forcing them to breathe pure nitrogen. It has been described as ‘a human experiment’ because it has never been used before in a judicially ordered execution.

Australia’s continued leadership in this area is strategically significant given that the list of countries around the world that still use the death penalty includes some of our key allies and regional neighbours. Examples include the US, Japan, Singapore and Indonesia. The practical reality is that the death penalty is an issue that needs to be carefully navigated by our law enforcement agencies as part of their routine interactions with retentionist neighbours and allies. For this reason alone, it is not an issue that we can ignore.

The second key reason that World Day Against the Death Penalty continues to matter in Australia is that we should never risk taking human rights for granted.

We can’t simply assume that future generations of Australians will automatically be abolitionist, or that they will understand why Australia’s opposition to the death penalty has, for so many years, been ‘bipartisan, multipartisan, unanimous, principled, consistent and well known’.

History teaches us that when it comes to human rights, progress can be reversed and hard-won rights and freedoms can easily be lost. We need to constantly renew and strengthen our commitment to human rights and freedoms, and make sure that the generations that follow are left in no doubt about why these things matter.

When it comes to the death penalty, we need to ensure that Australians continue to understand exactly why the death penalty should never be used. This includes that it is an irrevocable punishment and for that reason alone has no place in an inevitably imperfect criminal justice system. It is too often used disproportionately against the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, is not an effective deterrent, and is irreconcilable with both human dignity and the right to life.

Today is a day to remind ourselves of exactly why Australia stands against the death penalty. It is also an opportunity to renew our commitment to the efforts to consign the death penalty to history, not just in Australia but in every part of the world.