How to buy a submarine (2021 edition)

I’ll admit to being surprised when Australia announced the termination of the deal with Naval Group to build the Attack-class submarines. Not because I thought that shouldn’t happen—I’m on the record as saying that it looked like a seriously risky project from the start—but because it’s so rare for Defence and governments to resist the sunk-cost fallacy. But if the Attack class couldn’t be made to work, then it would be scandalous to add to the estimated several billion dollars already spent on the program.

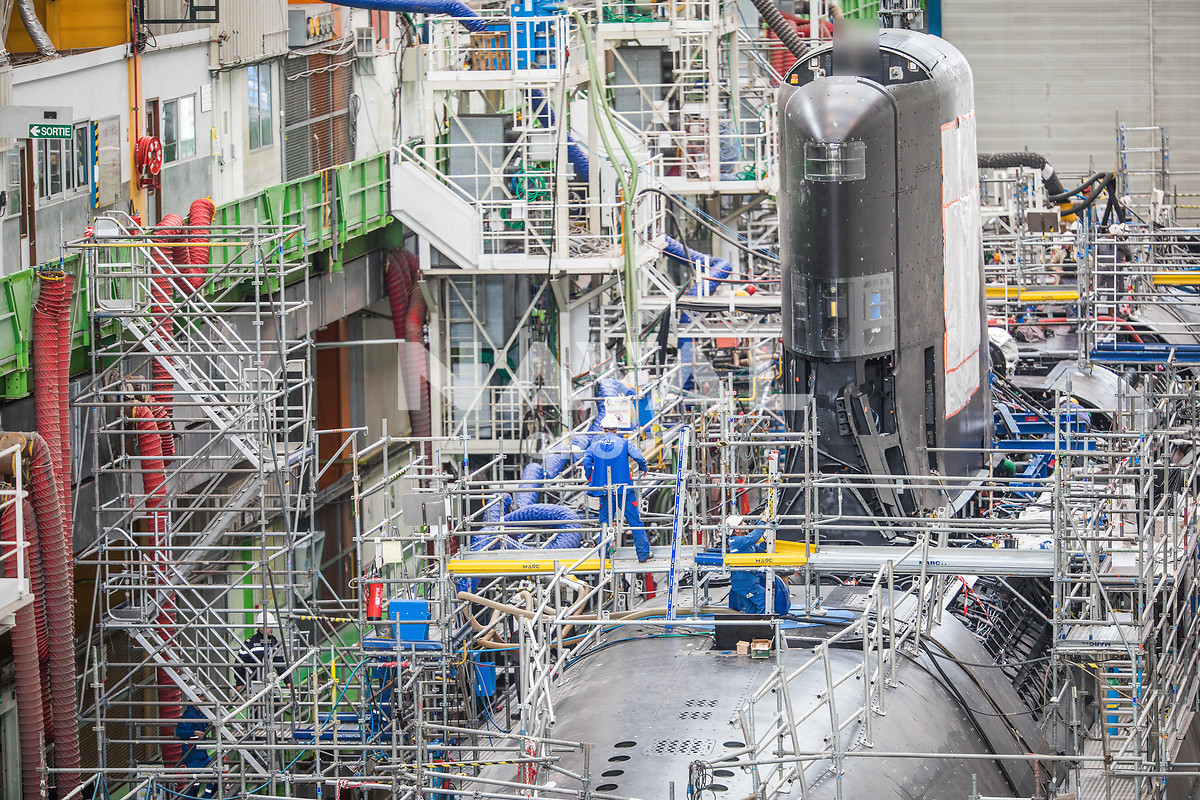

The Attack program timeline was also a concern, because the clock is ticking on the Collins class. Given the proposed level of complexity of the Attack class, further schedule overruns were likely. The Collins life-of-type extension—which is not without its own technical challenges—was proposed to buy time, but a disastrous capability gap between classes was a real prospect. There was a clear potential for a collapse in Australia’s submarine capability. We had already gone through that when transitioning from the Oberon to the Collins, and spent the next 15 years recovering.

Last week’s announcement does nothing to improve the prospective capability gap—and potentially makes it much worse. The design of a new class of nuclear attack submarine (SSN) isn’t an exercise that can be rushed, and there’s no established ability of Australian shipyards to build one, or of local industry to support one. No timeline has been specified as yet, other than the prime minister’s ‘hope’ that it will be before the end of the 2030s. But a delivery date somewhere on the other side of 2040 would seem more likely if we try to produce a bespoke Australian boat.

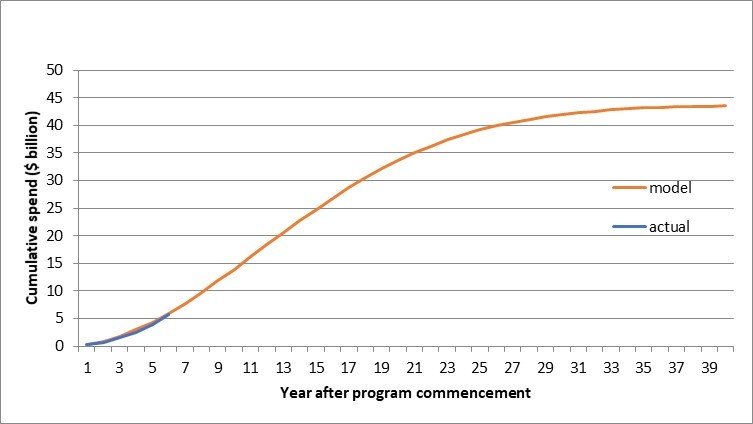

Given that the stated reason for the change of direction is our deteriorating strategic circumstances today, the disconnect is astonishing. If we’re serious about the role of a robust submarine capability in defending Australia’s interests, we need to find another way. I’ve had a couple of cracks at pitching a way ahead for the acquisition of the future submarines, with Sean Costello in 2009, and with Mark Thomson in 2014. Sean and I attracted some criticism for our ‘inflated’ estimate of a $36 billion price tag back then; now we look charmingly naive.

Those two papers—both titled ‘How to buy a submarine’—identified many of the challenges of risk identification and management in complex programs and pointed out the difficulties likely to ensue from the creation of a shipyard monopoly. Alas, the advice we proffered was trumped by the conspiracy of optimism that pervades the Department of Defence and by the politics of local shipyards.

In practice, Australia’s defence acquisition process has repeatedly shown itself to be very poor at recognising technical risk—see the technical and design issues surrounding the Hunter-class frigates and LAND 400 vehicles for the most recent examples. And successive governments have convinced themselves that supporting in-country naval shipbuilding makes it acceptable to slow down the delivery of defence capability, while paying more for it in the process. As a result, we have now lost a decade on the replacement for the Collins class and have the prospect of underemployed shipyards for the next several years.

But they say that the third time’s a charm, so let me suggest a couple of complementary approaches that might help sustain a national submarine capability and avoid the repeating of recent misadventures.

First, we need to accept now that the timelines mean that there’s no graceful transition from the Collins to a fleet of nuclear submarines. If Australia’s first SSN is launched in 2040, HMAS Collins will be 47 years old at the time, and already past a 10-year extension. Arriving at 2040 with few—or even no—operational submarines becomes a serious possibility.

So we are going to need a bridging capability. One option is leased nuclear submarines from the US or UK, though our dependence on the supplier for support and operation would reduce our ability to conduct independent operations. The other option is yet another acquisition, in the form of either an off-the-shelf boat or a Collins II design that draws on the engineering work done for the life-of-type extension. That would add more expense and consume more of Defence’s scarce engineering and project-management resources, but it would also allow the designing and building of the nuclear boats to be done in a measured fashion, and for the necessary Australian support infrastructure and skills base to be developed and matured.

Second, we need to take a hard-headed approach to the nuclear boats. We’re trying to become the first country in the world to operate SSNs without a domestic nuclear industry. That may be possible, but it suggests that we would be prudent to limit our ambitions for both innovation in design and industrial independence. It will make sense to maximise our leverage of the support capabilities of our UK and US partners in the enterprise and aim to acquire the most turn-key solution we can find, even if that results in less work for local industry.

If we learn nothing else from the Attack-class fiasco, we should accept that our collective ability to identify and manage project risk is poor. We’re about to embark on something that’s even more challenging in almost every respect and the risk of failure is high, so we should check our optimism at the door.