Zooming in on the latest flashpoint on the India–China border

On 9 December 2022, Indian and Chinese troops clashed in the Yangtse area along the India–China border. The confrontation in the Tawang region was the most serious skirmish between the two sides since their deadly clash in the Galwan Valley in 2020.

ASPI has released a new visual project that analyses satellite imagery of the key areas and geolocates military, infrastructure and transport positions to show new developments over the past 12 months.

This project contextualises India–China border tensions by examining the terrain in which the clash took place and provides analysis of developments that threaten the status quo along the border—a major flashpoint in the region. We find that the recent provocative moves by Chinese troops to test the readiness of border outposts and erode the status quo have set a dangerous precedent.

Tawang is strategically significant Indian territory wedged between China and Bhutan. The region’s border with China is a part of the de facto but unsettled India–China border, known as the Line of Actual Control, or LAC.

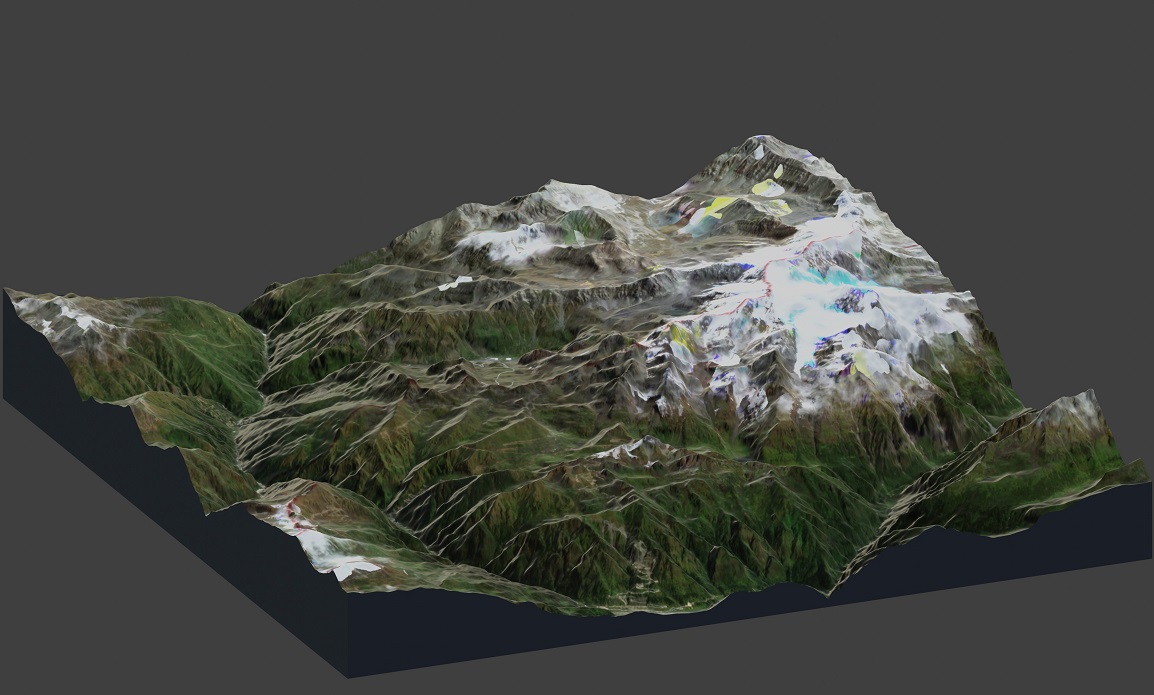

Within Tawang, the Yangtse plateau is important for both the Indian and Chinese militaries. With its peak at over 5,700 metres above sea level, the plateau enables visibility of much of the region. Crucially, India’s control of the ridgeline that makes up the LAC allows it to prevent Chinese overwatch of roads leading to the Sela Pass—a critical mountain pass that provides the only access in and out of Tawang. India is constructing an all-weather tunnel through the pass, due to be completed in 2023. However, all traffic in and out of the region along the road will still be visible from the Yangtse plateau.

Our analysis reveals that rapid infrastructure development by China along the border in this region means that it can now access key locations on the Yangtse plateau more easily than it could just one year ago.

India’s defences on the plateau consist of a network of six frontline outposts along the LAC. They are supplied by a forward base about 1.5 kilometres from the LAC that appears to be approximately battalion sized. In addition to this forward base, there are more significant basings of Indian forces in valleys below the plateau.

Although Indian forces occupy a commanding position along the ridgeline, it is not impregnable.

The access roads leading from the larger Indian bases are extremely steep dirt tracks. Satellite imagery shows that these roads are already suffering from erosion and landslides due to their steep grade, environmental conditions and relatively poor construction.

While China’s positions are lower on the plateau, it has invested more heavily than the Indian military in building new roads and other infrastructure over the past year.

Several key access roads have been upgraded and a sealed road has been constructed that leads from Tangwu New Village to within 150 metres of the LAC ridgeline, enhancing China’s ability to send People’s Liberation Army troops directly to the LAC. There is also a small PLA camp at the end of this road.

It was the construction of this new road that enabled Chinese troops to surge upwards to Indian positions during the 9 December skirmish.

The skirmish that took place between Chinese and Indian troops on the Yangtse plateau stems from this new infrastructure development.

Strategically, China has compensated for its tactical disadvantage with the ability to deploy land forces rapidly into the area. In small skirmishes, the PLA remains at a disadvantage because more Indian troops are situated on the commanding ridgeline that makes up the LAC. But in a more significant conflict, the durable transport infrastructure and associated surge capability that the PLA has developed could prove decisive, especially in contrast to the less reliable access roads that Indian troops would be required to use.

This intrusion, and subsequent clashes—which the Indian government claims the Chinese troops provoked—likely served to further normalise the presence of Chinese troops immediately adjacent to the LAC. This is a goal that the PLA appears to be working towards across the border and is part of China’s long-term strategy. By engaging in such an intrusion, the PLA is able to strategically position any ‘retreat’ to a higher location on the plateau.

Recent developments around Galwan and Pangong-Tso have shown that, where there is the political will, tense situations along the LAC can be disengaged with the involvement of both sides. In these areas, successful redeployment to positions back from the LAC has greatly reduced the risk of conflict.

Unfortunately, on the Yangtse plateau, the opposite is occurring. The recent provocative moves by Chinese troops to test the readiness of border outposts and erode the status quo have set a dangerous precedent.

China’s rapid infrastructure development along the border has created an escalation trap for India. It is difficult for India to respond to this new reality without being seen as escalating the situation. It is also difficult for it to unilaterally de-escalate without strategic concessions that would endanger its positions. India’s response has been to increase its vigilance and readiness along the border, including surveillance.

However, it is important to pursue non-military and multilateral measures in parallel to reduce the risk of accidental escalation and to position these incidents as a significant threat to peace and order in the Indo-Pacific. As part of this, India should seek and receive support from the international community to call out China’s provocative behaviour on the border.

Regional governments, including Australia’s, must pay greater attention to clashes on the India–China border. Continued escalation, including the potential of more serious clashes along the LAC, could become a major driver for broader tensions.

This new work by ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre builds on satellite analysis that it carried out in September 2021, focused on the Doklam region.