Wong and Marles should work to bridge Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic alliances

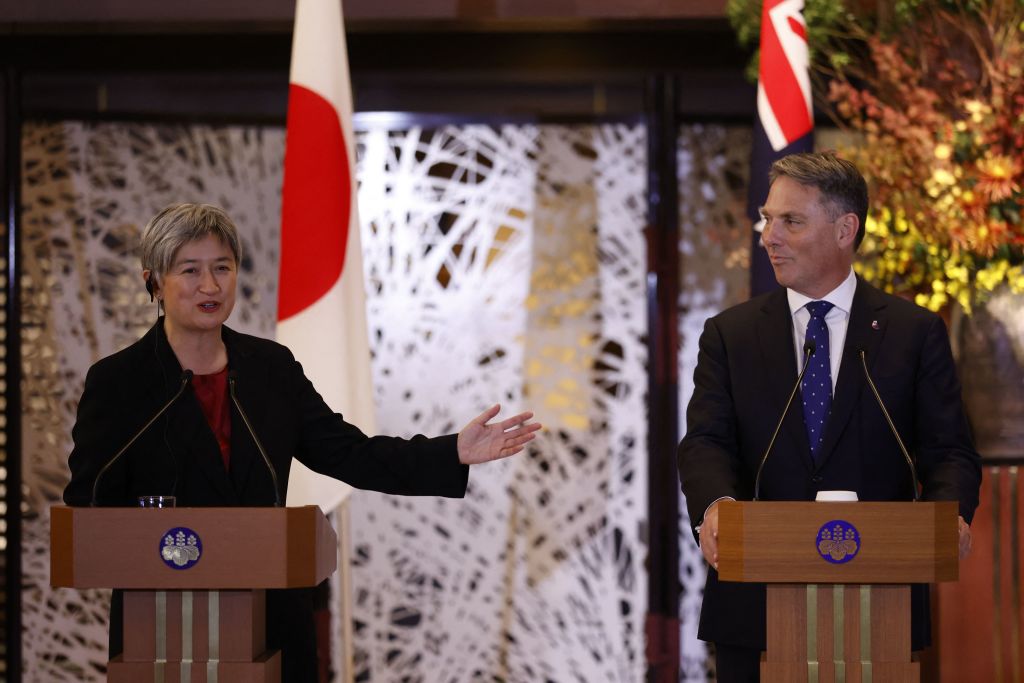

This week, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Defence Minister Richard Marles will travel to Europe for separate ‘2+2’ meetings with their French and British counterparts. Wong will also head to Brussels to meet the EU’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell. And Marles will travel on from Europe to Washington to meet US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin.

This visit is timely. The coalition effort to arm Ukraine has stepped up ahead of offensives anticipated in the northern hemisphere’s spring. Closer to home, Marles is expected to make significant announcements on the future of AUKUS and Australian defence policy in March.

With so much in play, each leg of this trip risks becoming dislocated and overly focused on the bilateral relationship at hand. Wong and Marles should strive to identify common threads connecting these relationships and their place within the wider strategic picture.

One strategic thread is AUKUS.

Part of Marles’ time with his British and US counterparts will be set over to the forthcoming announcement of the pathway towards Australian nuclear-powered submarines. But the AUKUS subs are unlikely to be the all-encompassing topic some expect. High-level discussions are probably more collegiate and less in the weeds of design options for the vessels than pundits like to imagine.

Beyond AUKUS, the focus on ‘modernising’ the Australia–UK relationship resonates with ‘operationalising’ the Australia–US alliance, which outgoing Australian ambassador in Washington Arthur Sinodinos said was the theme of the AUSMIN 2+2 in December. The logic is compelling: the world has changed, so Australia’s closest partnerships must evolve to deliver tangible outcomes at increased tempo.

The sequencing of these dialogues is important, as France—and Europe as a whole—has a stake in AUKUS, despite not being party to it.

Given the sense of betrayal left by the original AUKUS announcement that saw the dumping of the French Attack-class submarines, Australian ministers will feel obliged to brief French counterparts about the latest developments. There is a lot at stake for Canberra, including cooperation in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and trilaterally with India. Thankfully, the foreign minister’s media release augurs well, saying that the Australia–France 2+2 aims to ‘progress works towards a bilateral roadmap’. This might become the centrepiece of President Emmanuel Macron’s expected visit to Australia later this year. Further out, and with different branding, it might even be possible to include France in some of the advanced technologies under AUKUS’s so-called pillar two.

Despite improving relations, France’s initial outrage still taints some European views of AUKUS, as I heard when visiting Brussels last week. Wong’s meeting with Borrell is an opportunity to straighten out the record. But there’s no substitute for sustained engagement across European capitals. At the heart of EU and NATO decision-making are their member states, acting through the European Council and the North Atlantic Council respectively. Not all roads lead to Brussels when Canberra seeks to influence EU and NATO policy.

Which segues to the second strategic thread: the growing linkages between Indo-Pacific and Euro-Atlantic security.

There is already broad and growing consensus among friends on this point. Wong, Marles and their British and French counterparts can probably all agree with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken that China must learn the right lessons from Ukraine—namely that smaller countries, like Taiwan, can be expected to defend themselves rigorously and attract support for their defence, and that aggression will be collectively punished, including through sanctions and the redirection of trade and investment. The 2+2 joint statements should be explicit about the strategic implications of Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Marles and Wong can point to Australia’s support for Ukraine as evidence that Canberra is putting resources behind its interpretation of interconnected regions. Australian pledges to Ukraine—now approaching half a billion US dollars, mainly in military materiel—remain the most generous of any country outside the Euro-Atlantic, when viewed as a percentage of GDP. Today, members of the Australian Defence Force are in Britain training Ukrainian troops through Operation Interflex. Canberra is also playing a leading role building international cooperation on economic security and resilience against coercion. These are relevant to hybrid threats in domains like cyber where proximity and national or regional boundaries are less significant.

Britain and France also appreciate regional strategic connectivity. They have made similar contributions to Ukraine in monetary terms, although Britain arguably deserves more credit for galvanising allies, as shown recently by the Tallinn Pledge and early announcement of main battle tank transfers. Both countries also seem committed to their Indo-Pacific strategies and the resource commitments they entail. And both are building Indo-Pacific partnerships and interoperability, including the recent signing of a UK–Japan reciprocal access agreement, which follows a similar agreement between Canberra and Tokyo.

Some in Europe are already thinking more ambitiously. The chairman of the UK parliamentary defence select committee, Tobias Ellwood, has called for Britain and France to join a NATO-like arrangement that encompasses a range of Indo-Pacific countries, including all members of the Quad. That’s a bridge too far. It overlooks the historical preference for looser institutions and minilateralism in the Indo-Pacific. The NATO comparison would also play into the hands of Chinese propagandists.

A more subtle and suitable approach would be to build on NATO’s existing engagement with its four Asia–Pacific partners (known as the AP4): Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand. Reflecting concerns about China raised in NATO’s 2022 strategic concept, these links are already growing on a country- and issue-specific basis. The AP4 leaders attended the 2022 NATO summit in Madrid and are expected to be invited again to this year’s summit in July in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius.

Marles and Wong cannot meet NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg while they’re in Europe because—to illustrate the point about regional connectivity—he’s visiting South Korea and Japan this week to discuss topics like emerging and disruptive technologies.

Even so, Marles and Wong could sound out their French and British counterparts about expanding the AP4 into an Indo-Pacific format. Such a format could seek to engage a wider range of countries, notably India. This wouldn’t imply any sort of new collective security arrangement. Rather, an ‘IP5’ could be a platform to discuss key shared concerns, like post-Ukraine approaches to effective deterrence, without obligation or institutional lock-in.

The challenges we face in the era of the China–Russia ‘no limits’ partnership—including Ukraine, Taiwan and borderless hybrid threats—can only be confronted by re-coupling our regions. Marles and Wong should weave that strategic thread through their trip to Europe.