Washington needs to ditch its America-first approach to critical minerals

Over the past few years, Covid-19, climate change and Chinese economic coercion have catalysed rapid global economic, foreign relations and national security policy changes. In Australia, the public discourse on sovereignty, national capacity and secure supply chains is one area where this change is particularly evident. These discussions have more recently prioritised the supply and value chains for critical minerals and rare-earth elements because of their links with advanced and low-emissions technologies.

In some countries, these policy challenges have given rise to responses based on a new version of economic nationalism. Sovereign critical mineral and rare-earth resilience is beyond the reach of any one country. Unilateral responses will not produce secure or reliable supply chains. Indeed, economic nationalism may actually aggravate the problem.

A critical mineral is a metallic or non-metallic element that is essential for modern technologies, economies or national security and has a supply chain at risk of disruption. Geoscience Australia lists 26 critical minerals ranging from graphite to magnesium.

The rare earths are a subset of critical minerals and comprise 17 metals—15 elements from the lanthanide series and two chemically similar elements, scandium and yttrium. All have unique properties that make them vital for various commercial and defence technologies, including batteries, high-powered magnets and electronic equipment.

Chinese economic coercion and ham-fisted domestic policy have highlighted the risk of disruption to global rare-earth and critical mineral supply chains.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian was right when he said: ‘No one should use the economy as a political tool or weapon, destabilise the global industrial and supply chains or punch the existing world economic system.’ Yet that is precisely what the Chinese Communist Party has been doing for the past decade with rare earths.

In 2010, the CCP effectively restricted rare-earth exports to Japan after a Chinese fishing trawler collided with a Japanese coastguard vessel near the disputed Senkaku Islands.

More recently, it threatened to limit rare-earth supplies to US defence contractors, including Lockheed Martin, over US arms sales to Taiwan.

But the problem isn’t just about economic coercion; the CCP’s domestic policy has had other serious consequences. In 2021, the central government began actively monitoring energy consumption across China. Later that year, Shaanxi province fell victim to the country’s ‘double control’ when it failed to meet energy consumption targets. The CCP swiftly shut down high-energy-intensity industries, including aluminium production. An international supply crisis ensued, and prices have soared.

China’s coercive actions and domestic policies represent unacceptable economic and resilience risks to rare-earth and critical mineral supply chains. Diversified supply chains are now needed to mitigate the economic and national security risks associated with disruption.

Japan has led the way in responding to China’s dominance of the rare-earth market. Its investment in Australian company Lynas Rare Earths should provide confidence in an alternative, resilient supply chain. And its approach reveals the superiority of collaborative responses over economic nationalism.

Other nations, like the US, have been slower to recognise the benefits of a coordinated response, showing early signs of a preference for an America-first approach. However, in doing so, the US may deny itself and its allies the opportunity to achieve resilience through approaches that engage with such concepts as near-shoring and friend-shoring.

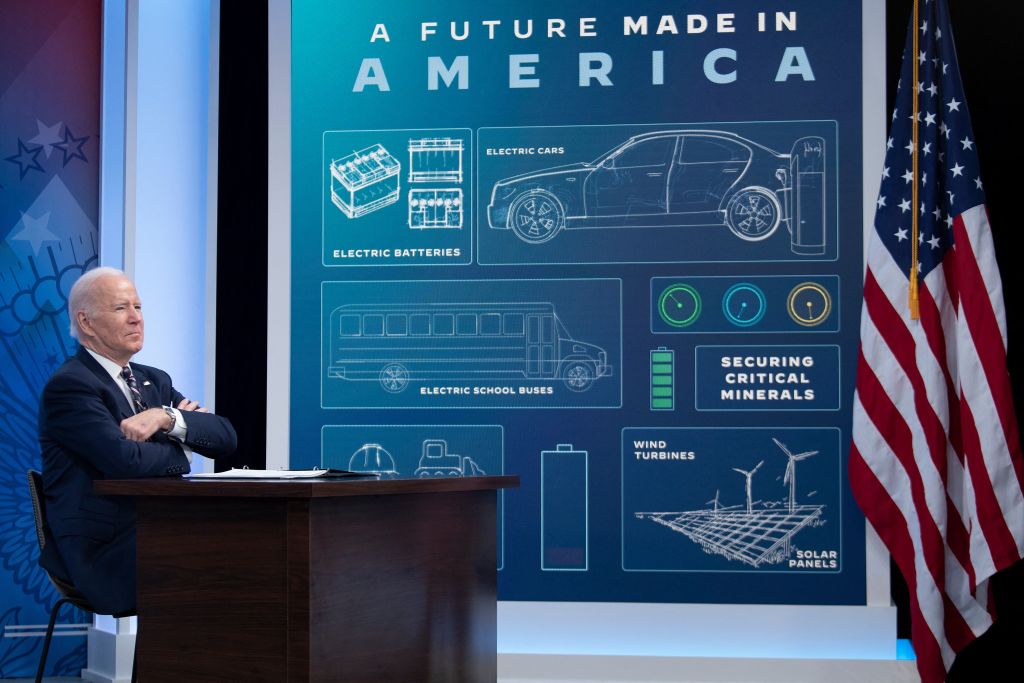

The landmark US Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, is a case in point. The act is intended to catalyse investments in domestic manufacturing capacity; encourage procurement of critical supplies domestically or from free-trade partners; and jump-start research, development and commercialisation of leading-edge technologies such as carbon capture and storage and clean hydrogen. It was passed by the US Congress and signed into law by President Joe Biden in August 2022.

Many of the IRA’s tax incentives are aimed at quickly scaling up domestic production and domestic procurement. For example, to unlock the full tax credit for an electric vehicle, a percentage of critical minerals in the vehicle’s battery must have been extracted or processed in the US or in country that is a US free-trade partner. The percentage will increase by 10 percentage points each year, from 40% in 2023 to 80% in 2026.

The IRA, even with its reference to free-trade partners, creates advantages for domestic US rare-earth and critical mineral supply and value chains that will impact Australian industry.

In its submission to the IRA, Australia encouraged the US to consider policy measures that acknowledged Australia’s role as a secure, reliable and trusted free-trade partner that can support achieving the IRA’s objectives.

The IRA could be a disincentive for North American companies to enter into mineral offtake or processing agreements with Australian companies or battery manufacturers. BHP CEO Mike Henry argues that the IRA ‘has improved quite markedly the attractiveness of the US as an investment destination’. He also notes that the act has ‘stimulated other countries into the race, and they’re now trying to compete in their own way’. The rapid growth of the US sector is also likely to intensify competition for labour, materials and capital.

In the face of great-power competition, geostrategic uncertainty, more regular global disruption and domestic narcissism, the US must avoid reflexively responding with economic nationalism. Recent reports have indicated that the US government is exploring the development of ‘narrowly focused trade pacts on critical minerals with Japan and the UK, in addition to talks with the European Union’.

Australia is investing heavily in growing its manufacturing capability and should be a partner of choice for the US industry to support diversified and resilient supply chains. Given Australia’s important role in the Indo-Pacific and its enormous potential to supply rare-earth elements and critical minerals, the US should be looking in our direction as a matter of priority.

Next month, ASPI, with the Northern Territory government’s ‘Investment Territory’ program, will host the inaugural Darwin Dialogue. The 1.5 track dialogue will bring together government, industry and academia representatives, including delegations from Japan and the United States, to discuss establishing secure supply and value chains for mining, processing and refining critical minerals outside China.