UN Security Council bid: thinking the unthinkable

We will know around Friday afternoon whether Australia has been successful in winning its bid for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Having just returned from a trip to New York, the vibe I picked up there was cautious, perhaps even a little worried, about our chances. Our rivals for the seat, Finland and Luxembourg, have run effective campaigns and are not be underestimated: the outcome could be nail-bitingly close. Anthony Bergin and I wrote last week about why it’s very much in Australia’s interest to hold a seat on the Security Council. We are a middle power with global interests and being able to steer the UN—imperfect as it is—along tracks important to us is no small benefit. But good strategists also consider the down side risks: what happens if we lose the bid?

First up, recrimination will be the order of the day. A loss will mean that this weekend’s media will be full of astonished pundits expressing wonder about how it is that two of Europe’s minnows beat us to the seat: ‘Luxembourg, are you serious?’ It will be like losing the World Cup bid to Qatar. No attention will be paid to the fact that our competitors were campaigning for years before Australia started its bid. As the world is seen from New York, no one owes Australia a free lunch no matter how consequential we think we are. Although the Opposition has endorsed the bid in a low key way, a loss will lead to predictable charges of mismanagement. Some might wonder why the Prime Minister was bought so strongly and publicly into the last weeks of the campaign.

After the anger comes the grieving, accompanied by soul-searching about Australia’s place in the world. One productive way to channel this emotion would be to review Australia’s overseas diplomatic presence. The Lowy Institute has catalogued in persuasive detail the inadequate state of our diplomatic presence. With only five missions to cover Africa and with multiple posts with only one or two Australian staff, DFAT has been strangled for resources for the better part of fifteen years. In a world becoming more competitive and multipolar, Australia must increase resourcing for our diplomatic effort abroad or else risk losing influence. Take the UK as an example; in vastly more difficult financial circumstances than ours, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is increasing its diplomatic presence across Asia by 110 people. By comparison, in North Asia our total Australian based DFAT presence is 68 (with 182 in Southeast Asia). We shouldn’t be puzzled that we struggle to have our voice heard internationally.

Predictably, there’ll be those in Australia who oppose our alliance with the US and will claim that a failed bid is the result of us being too close to Washington and that a more ‘independent’ Australian foreign policy would have garnered more votes. The alliance may lose us some votes but it will undoubtedly gain others. Most Permanent Representatives at the UN will vote on the basis of a colder calculation about where their national interests resides. An important component of Australia’s global prominence (such as it is) comes from the value-add the US alliance gives us: a quality Defence Force; a capacity to meaningfully participate in peacekeeping and coalition operations; a serious minded and informed approach to security issues. In short our alliance strengthens the case for a Security Council seat.

A final consequence of a loss for Australia is that it will create the most unpromising environment for the government to launch the now overdue report on Australia in the Asian Century. I’ve written about the curiously 1990s feel to the discussions about this report, with its apparent focus on our relations with seven countries in Asia. It remains to be seen if that characteristic is still evident after the White Paper’s reported make-over in the last few weeks. I’m speculating here, but if we do lose, some dots should be drawn between that event and a narrowly focussed Asian Century White Paper or the fact that it’s been overdue for some time now. As Asia goes global we might ask why Australia’s interests are served by narrow-casting our interests in the region. Expect then a return to the debate of whether Australia is a country with Asian or wider global interests.

Let’s hope that the bid is a success. The consequences of not winning the UN seat would be bad for our interests and, in fact, bad for the UN because Australia would be a committed and creative Security Council member. Even if we’re not successful, the right thing to do would be to forgo recriminations and instead fix the problems that are weakening our international presence in an increasingly complex international environment.

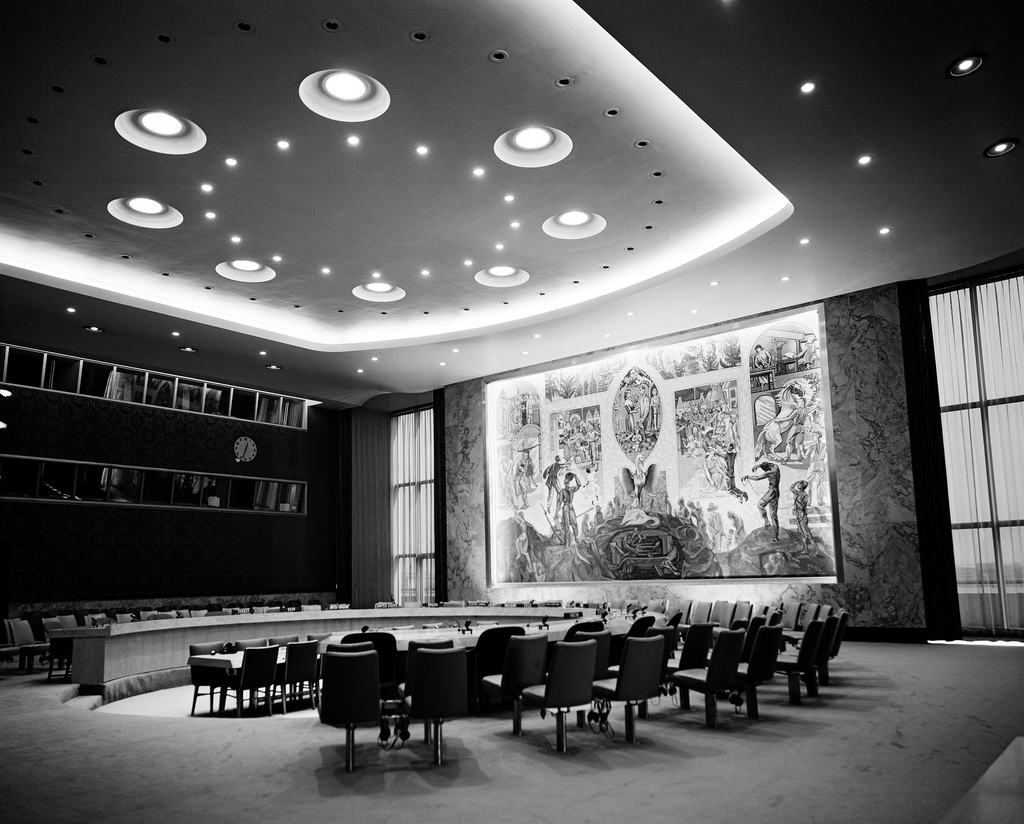

Peter Jennings is executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Image courtesy of Flickr user United Nations Photo.