Ukraine: why we must stay the course

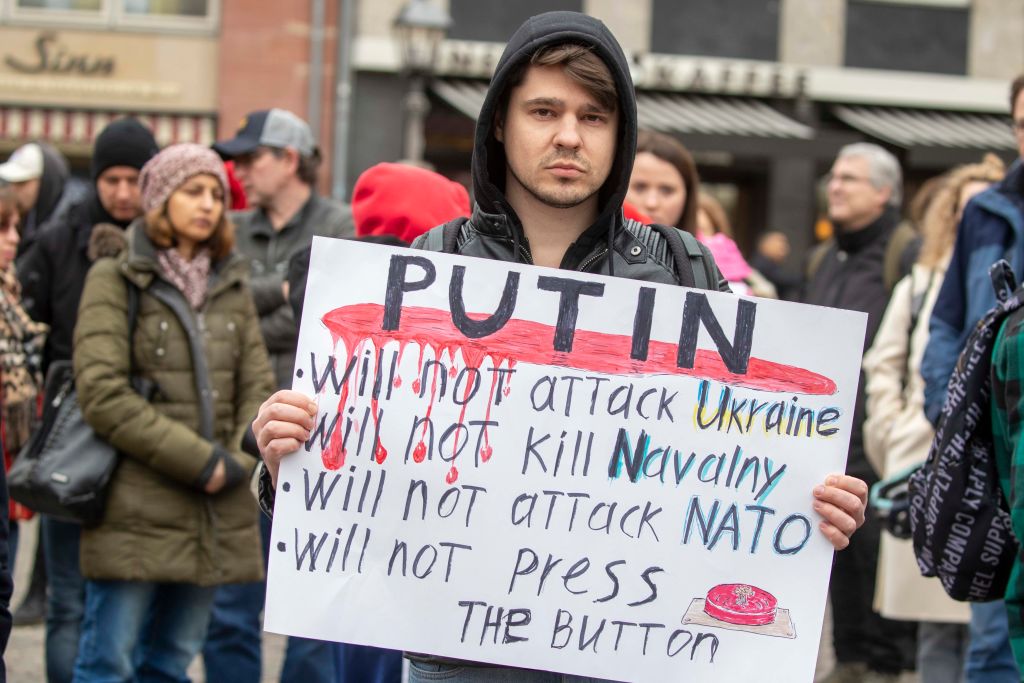

On 24 February, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin began his war of subjugation and extinguishment against Ukraine. He was not alone in thinking it would be a quick victory. He was certain he had the measure of ‘the West’, believing it to be irresolute, stricken with moral turpitude and in terminal decline. It would, he thought, acquiesce to another burst of resurgent Russian imperialism, as it had in 2008, when Russian forces assaulted Georgia, and in 2014, when Russia illegally occupied eastern Ukraine and annexed Crimea.

Two years later, with continuing—but just sufficient and sometimes wobbly—support from the West, Ukraine has proven Putin and the sceptics wrong, albeit at enormous cost. No-one knows exactly how many Ukrainians have been killed in battle, massacred in their homes, or have died when Russia has plunged its missiles into non-military targets in deliberate breach of the law of armed conflict. Ukraine’s infrastructure and economy have been battered and its environment laid waste. The UN assesses that more than 10 million of Ukraine’s 42 million people have been displaced within and outside the country.

Conservative estimates put Russian losses at no fewer than 315,000 dead and wounded. Yet Russian forces occupy around 18% of Ukraine’s territory within the borders that were internationally recognised, including by Russia, when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Russia twice had guaranteed the integrity of those borders and foresworn the threat or use of military force or economic coercion to undermine Ukraine’s political and territorial sovereignty, in the 1994 Budapest Memorandum and the 1997 bilateral treaty on friendship and co-operation.

So much for the Kremlin’s solemn undertakings, past and future.

As Ukrainians keep dying in defence of their independence and more Russian lives are sacrificed to a revanchist’s obsessive nostalgia for an unrecoverable imperial glory, Australia—which already has contributed $960 million worth of direct and indirect military and financial support—must stay the course at Ukraine’s side. We should return our ambassador to Kyiv. Ukraine should have first option when we dispose of potentially useful military platforms and equipment.

Of course, the government must balance other demands, like the appalling conflict in Gaza, the needs and challenges of our immediate region, and the daily distractions of fractious democracy. But the war in Ukraine has dimensions that touch our core interests in upholding the rule of law and the resilience of our democracy.

Putin’s rationalisation of his war of choice is baseless, as Professor Timothy Snyder demonstrated in his dissection of the recent Tucker Carlson interview. We should give no credence to the Kremlin’s shape-shifting justifications for unleashing war in Europe. These have rambled across preventing ‘genocide’ against ethnic Russians in the Donbas region, through ‘denazification’ and ‘demilitarisation’ of Ukraine, to defending Russia’s unique status as a morally superior ‘civilisation’—the keeper and defender of ‘traditional’ values against Western woke-ness.

The Russian journalist, Mikhail Zygar, thoughtfully argues that the latter theme is deliberate Russian statecraft, aimed not just at a domestic audience but also seeking common cause with ‘insurgent right-wing politicians’ who are threatening mainstream leaders in countries that have been key in isolating Russia. This is a warning we ignore at great risk to the health of our own democracies, even in distant Australia.

Russian propaganda is adept at working with the grain of Western societies to sow disharmony and distrust and to fertilise suspicion about the intent and integrity of our own governments. This demobilisation of public sentiment serves the Kremlin’s cause. We must resist and arm ourselves to tackle this creeping challenge before it takes firmer hold. A good starting point would be to resuscitate ailing Russian language and associated studies at our universities, to boost ‘Russia literacy’ and comprehension of a country which remains a significant player in the world and matters to countries that matter to us. Perhaps we could even add a dose of Ukrainian studies for good measure.

The Kremlin had championed its war of aggression in Ukraine as the rightful recovery of historical lands that were part of Russia’s post-Soviet birthright. Yet now it casts this as an existential battle against the combined forces of NATO and the West that, Putin preposterously asserts, seek nothing less than the physical dismemberment of Russia. It patently is lost on the Kremlin and its strategists that it is Russia’s own policies and actions that have worsened Russia’s strategic position, not least by driving Sweden and Finland to overturn decades of armed neutrality and seek NATO membership. This simple truth ought to neutralise the addled furphy of ‘NATO expansion’ routinely peddled by Putin’s propagandists and their acolytes around the world, including, regrettably, in Australia.

The crux remains Putin’s assertion in his July 2021 essay that Ukraine has no real historical claim to independent existence. His disregard of modern history and the rule of law—including resolutions of the UN Security Council, of which Russia is a permanent member—proves Putin is committed to a long game, regardless of the ebb and flow on the battlefield. That is also evident in his making common cause with two objects of UN Security Council sanctions, North Korea and Iran, for the supply of munitions, drones, and other military materiel to support Russia’s lawless war. Why is this not cause to reject the Kremlin’s narrative and its claim to any kind of moral superiority?

Our political culture inclines us to want to solve problems that sometimes can only be managed over the long term, while weathering the short-term vicissitudes of domestic electoral cycles. Such is the challenge we face with Putinist Russia. For longer than we have comprehended, the Kremlin has believed it is at war with ‘the West’, including Australia. Putin declared as much in his seminal speech at the Munich Security Conference in February 2007—coincidentally, the same event at which Yuliya Navalnaya last week denounced the Kremlin’s slow-motion murder of her husband, oppositionist Alexei Navalny, who died in an Arctic prison camp on 16 February.

Putin has already ruled Russia for the equivalent of eight Australian parliamentary terms. The usual chicanery that marks Russian presidential elections means he will retain his throne this March for another six years and, health permitting, doubtless will run again and be re-‘elected’ in 2030 for six more. That totals 12 Australian parliamentary terms. Regardless of his own mortality, the highly centralised system of rule which Putin has refined over the last 24 years means ‘Putinism’ will persist.

So Australia and our similarly minded partners should understand that we must contend for at least another generation with a crucial member of the UN Security Council, of APEC, and of the G20 which, as my former UK colleague in Moscow, Sir Laurie Bristow, put it, is possessed of an ideology ‘constructed on a heady mix of entitlement and victimhood’ born of the USSR’s sacrifices in World War II and the attendant claim to ‘a buffer zone in central and eastern Europe after 1945’.

Eight years ago, I asked a prominent Russian opposition politician in Moscow how to respond to the Kremlin’s increasingly confrontational approach to its opponents and critics at home and abroad. His reply was: ‘First, put your own house in order; you were the most use to us when you were something we could aspire to become. Second, speak truth to power; do not shun the hard conversations. Third, if you do not back your rhetoric with resources, you neither are serious, nor will you be taken seriously.’

Those words resonate to this day.