Top ten with a bullet?

One part of my talk at the Australian Defence Magazine’s annual defence industry conference that didn’t make it into my previous post was a digression about the recently released defence export strategy. Rob Bourke’s recent post picked up on a few of the points I covered, so I’ll confine myself to a critique of the government’s stated aim of making Australia a ‘top ten’ supplier of armaments.

As Rob already pointed out, establishing a baseline of the current level of defence exports isn’t as easy as you might hope. There’s no single unambiguous source of data, and the $1.5–2 billion figure in the strategy isn’t obviously relatable to specific products. Defence used to issue an annual report on Australian arms exports, but that stopped after 2003–04. More recently the Defence Export Controls office has put out a statistical report of export permit applications and their outcomes. That data is incomplete and potentially misleading for two reasons. First, not every approved application results in exports to the full value of the approval. Second, it’s not mandatory for exporters to provide the department with the value of the goods or services in question—some do and some don’t.

With all those caveats, it’s hard to do solid analysis—at least if we’re depending on accurate in-year values. But it’s still possible to make some observations about relative performances over time and in comparison to other countries. The necessary data resides in the arms transfer database maintained by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Their bespoke methodology for denoting the value of arms sales includes a ‘trend indicator value’ (TIV) that ‘represent[s] the transfer of military resources rather than the financial value of the transfer’. The SIPRI numbers have been misread by some as dollar figures, but it’s not a bad way to smooth out the quirks of the international arms market—such as arms deals that aren’t cash transactions, but involve complicated trade arrangements in part or whole payment.

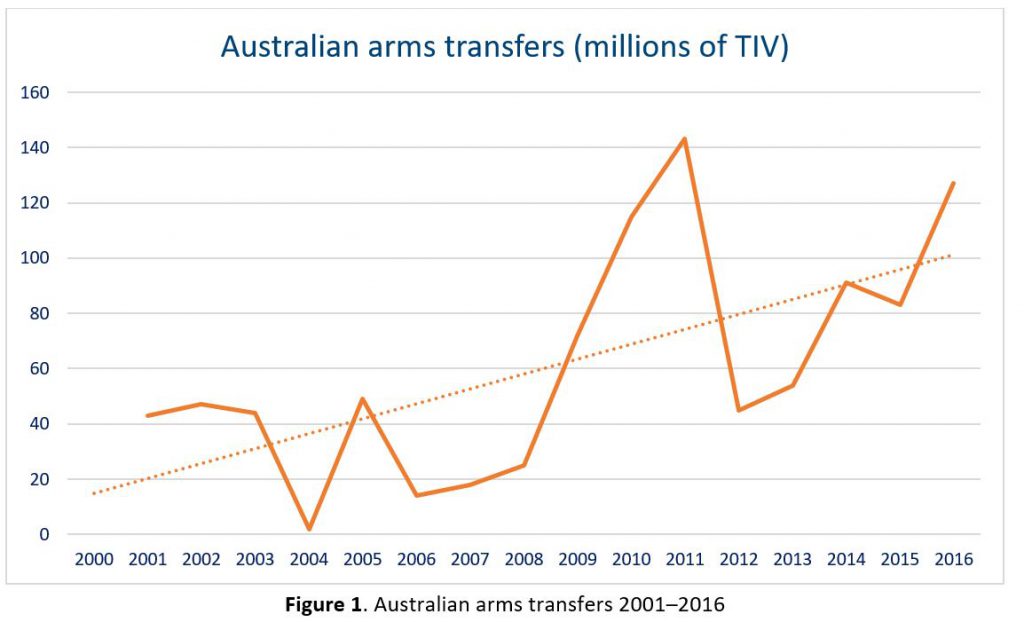

Figure 1 above shows Australian arms exports since 2001, in TIVs. The data is volatile, but there’s an underlying average annual increase of about five million TIVs (dotted line). So the government’s defence export drive builds on an existing trend. (Although that reasonably strong long-term growth raises the question of just how much additional government assistance is needed.) More careful management of existing assistance—better marketing and a focus on matching local production to customer needs—could boost the market for Australian-produced weapons.

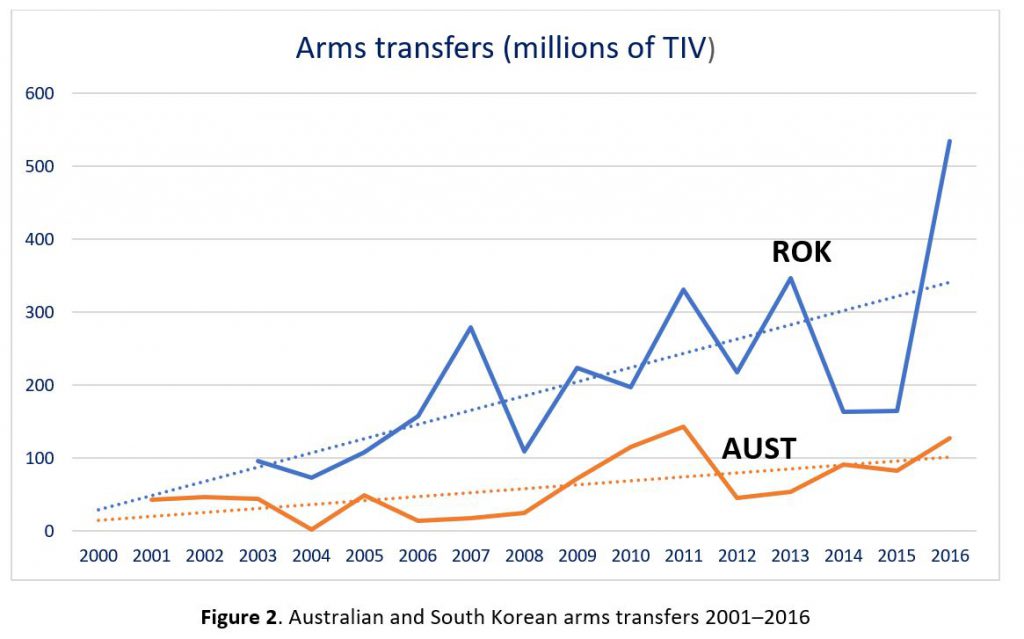

So far, so good. But Australia isn’t the only country aiming to sell more defence materiel to help grow its economy and offset the cost of producing its own weapons. Many of the countries on the identified list of future market growth are trying the same thing—especially the UK and the US. To see how hard it might be to move higher up the ladder, Figure 2 shows the comparative data for Australia and South Korea (ROK). I chose South Korea because it’s a country not dissimilar to Australia in terms of size, and because at number 15 it sits pretty much midway between Australia’s spot at number 19 and the top ten spot we’re covetously eyeing.

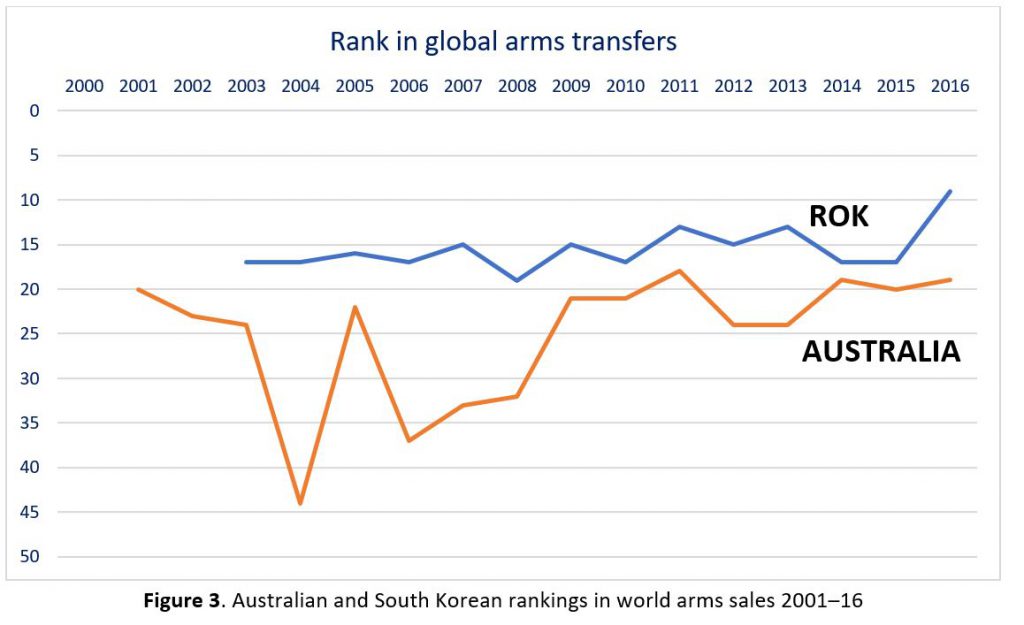

Figure 3 shows the ranking of the two countries over time. The ROK has been between 19th and 13th for the past 18 years, making a big leap last year into 9th place. That was almost entirely due to one big sale of trainer aircraft to Iraq—about which more later.

The main takeaway from those last two charts is that the ROK has mostly trod water in the rankings since 2001, despite increasing its arms sales more than twice as fast as Australia. To get past the ROK (and other intervening nations), we’d need to at least triple the growth in our sales over an extended period. It’s possible, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

To see how hard it can be to move relative to other countries all trying to do the same thing, back in 2006 the Howard government had ambitions to make Australia an energy exporting ‘superpower’. At the time Australia was in 8th place on the world export rankings with a market share of 2.4%. A decade later we were still in 8th place with the same market share—and that’s in a field where we have comparative advantages.

Finally, it would be remiss not to mention ethical concerns about arms sales. Aid and other groups have been vocal in their opposition to the new push. There are moral hazards in selling weapons, such as exported materiel turning up on the ‘wrong’ side of a conflict or being used in questionable operations. (And not just sales—helicopters gifted by Australia to PNG in the 1990s ended up being used in offensive operations in Bougainville, despite the PNG government previously agreeing to quarantine them from such use.)

And there are hazards even if nothing gets used ‘incorrectly’. Some of the biggest companies in the defence world—including some we deal with—have been found to have engaged in illegal deals, particularly when selling to countries where corruption and bribery are an established part of the business landscape. And, as a salutary reminder, there are some very big question marks over the very transaction that pushed the ROK into the top ten for the first time.

There are lessons in others’ experiences. The UK has had success with its ‘team UK’ model of deep cooperation between the government (including the armed forces) and British companies to win contracts. That can involve subsidies, offsets, or side deals and payments. But the pressure to secure deals can make what looks like a good idea at the time look less good later. Big defence deals have long tails, and have at times led to allegations of corruption and other scandals for companies and governments. Avoiding those pitfalls will require judgement of what’s in Australia’s interests, a clear and viable commercial business case, and transparency about the transactions. All that will make going up the export leader board that much harder.