The structure of a diplomatic revolution

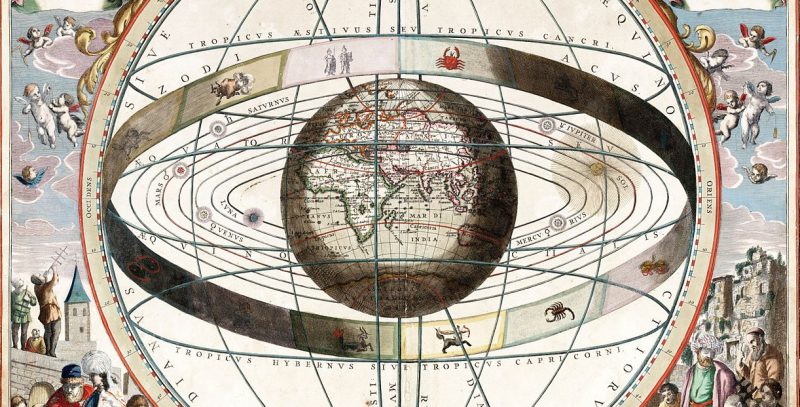

It has been nearly 60 years since the philosopher and historian Thomas Kuhn wrote his influential book The structure of scientific revolutions. Kuhn’s thesis was simple but heretical: breakthroughs in science occur not through the gradual accumulation of small changes to existing thinking, but rather from the sudden emergence of radical ideas that cause existing models to be replaced with something fundamentally different. As was the case when astronomers determined that the earth revolves around the sun and not vice versa, these ‘paradigm shifts’ usher in an entirely new model that becomes the basis for ‘normal’ scientific study and experimentation until it, too, is replaced.

I mention Kuhn because his idea is as relevant for social science as it is for natural science. The example I have in mind is the contemporary Middle East, where the current paradigm between Israel and its neighbours has prevailed for more than half a century.

Nearly everything said and written about the issue reflects the outcome of the June 1967 Six-Day War, which left Israel in control of territories that had previously belonged to Jordan (East Jerusalem and the West Bank), Egypt (the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza) and Syria (the Golan Heights). Since then, the ‘normal’ diplomatic model (enshrined in UN Security Council resolution 242 and subsequent resolutions) has assumed that Israel would trade this territory in exchange for security and peace.

For some time, the paradigm appeared to have validity. Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt, allowing the two countries to sign a peace treaty that has endured to this day. Years later, Israel and Jordan normalised their relationship. Negotiations between Syria and Israel came close to succeeding, but failed in the end, largely because Syria’s president, Hafez al-Assad (the father of current Syrian President Bashar al-Assad), was unwilling to sign on to a compromise.

It is no longer possible to imagine peace talks, much less agreements, between Assad’s government and that of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The Israeli government long ago annexed the Golan Heights, and now Assad’s government increasingly depends on Israel’s archenemy, Iran, for its survival, and instead of negotiations, we see Israel attacking Iranian forces and equipment on Syrian territory.

Diplomatic progress between Israel and the Palestinians is equally difficult to imagine. This wasn’t always the case. Negotiations came close several times to establishing a Palestinian state alongside Israel under terms that both sides could accept. But at the last minute, Palestinian leaders baulked, fearing that agreeing to less than what they had historically claimed to be Palestine would leave them politically vulnerable to hardliners who believed that compromise was unnecessary because time and world opinion were on the Palestinians’ side.

This was a historic error. What was on offer in the past is no longer. Israeli politics has shifted decisively rightward. Jewish settlements on the West Bank have grown dramatically in terms of both area and population. Netanyahu explicitly promised during the recent election campaign to begin annexation of the West Bank. US President Donald Trump, whose administration moved the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and reversed nearly 40 years of US policy by recognising Israel’s authority over the Golan Heights, may well support further Israeli annexation.

Much of the world has grown weary of the conflict. Quite a few Arab governments, worried about Iran or internal threats more than Israel, are prepared to work with Israel quietly, and in some cases openly. Splits within the Palestinian leadership are exacerbating persistent divisions on what to ask of Israel and what to accept.

The Trump administration may well unveil a peace initiative in this context. But its proposal is unlikely to deal with the territorial, political and refugee issues that are central to the creation of a Palestinian state. A Trump plan is more likely to focus on offering economic incentives to Palestinians in an effort to encourage them to compromise. It is unlikely to succeed.

The most likely future is thus one of drift. Palestinians will continue to have limited autonomy in parts of the West Bank and Gaza. At some point (one we have neared, if not reached), the potential for a viable Palestinian state will cease to exist.

All of this poses a risk to Israel as well. There is an unresolvable tension between Israel remaining a Jewish state and a democratic one if it continues to exercise political control over millions of Palestinians who are not Israeli citizens. Avoiding this choice and maintaining the status quo will frustrate Palestinians and increasingly isolate Israel in the region and the world (especially if annexation occurs).

Some will argue that this assessment is too bleak. I hope they are right. But even if they are, the benefits of progress between Israelis and Palestinians will not spread. Closely associated with the territory-for-peace paradigm was the belief that, by ushering in peace between Israel and its Arab neighbours, an Israeli–Palestinian settlement would enable the region to flourish. But resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict will not end the civil war in Syria or the slaughter in Yemen, curtail Iran’s nuclear ambitions, restrain Saudi Arabia’s leaders, or ameliorate the repression and corruption that are commonplace throughout the region.

So even if the Israeli–Palestinian conflict were to end, the Middle East’s problems would not. And there is no reason to predict the Israeli–Palestinian conflict will end. It is time for a paradigm shift in how we think about the Middle East, not because a better diplomatic model has presented itself (it has not), but because the current paradigm is increasingly at odds with reality.