The road to Tokyo, via Washington DC

Recently, commentators have argued that Australia should seek closer defence ties with Japan. In his AFR column, Peter Jennings suggested that to consider China’s reaction to such ties would be to ‘let China think their disapproval can veto our foreign policy aims’. Paul Kelly adopts a similar tone in The Australian, suggesting that critics of deeper ties are ‘radicals…[who] seem to want a fundamental shift in our foreign policy…aspiring to a realignment towards China’. Both authors present a false dilemma which disparages those concerned about Australia’s creep toward a strategic alignment with Japan. Despite their suggestions, it’s possible to condone limited defence cooperation with Japan and also be cautious about risks posed by ever-deepening ties.

First, consider just how quickly tensions between Beijing and Tokyo have intensified. After Japan nationalised the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in September 2012, Chinese military planes began flying directly towards them. In December 2012, a Chinese aircraft breached Japanese airspace and took photos of the islands. In January 2013, a Chinese frigate activated its fire-control radar on a Japanese vessel—the naval equivalent of pointing a pistol at someone. In November 2013, China announced an Air Defence Identification Zone, essentially claiming sovereignty of the airspace over the disputed islands. Recently, there were reports of Chinese planes flying dangerously close to Japanese aircraft (as close as 30 metres in one case). If that trend continues, a violent confrontation seems a question of when, not if.

The most salient issue in this discussion is the strength of the US–Japan alliance, and on this subject there should be no foregone conclusions. If this alliance remains healthy, and if China’s aggression toward its neighbours doesn’t increase, then closer ties between Australia and Japan aren’t needed. Let’s agree to build submarines together, but keep it at that. The US can use its alliance to influence and support Japan, and we can avoid needlessly antagonising China.

But America’s reluctance to confront China raises questions about its regional security role. The US talks about its national interest in preventing unilateral changes to the status quo, but it has done little to prevent such changes in Asia. China still controls the Scarborough Shoal (which it seized from the Philippines in 2012), and its recent decision to station an oil-rig in Vietnamese waters attracted only verbal condemnation. Yes, the US challenged the ADIZ and has flown intelligence aircraft over the oil-rig and the Scarborough Shoal, but those are pretty low-risk moves. The US hasn’t yet devised a low-risk strategy to counter China’s more direct aggression, which explains why Beijing may see the ‘Scarborough model’ as a template for further revanchist behaviour.

President Obama has stated that America’s alliance with Japan would apply in a Senkaku Island scenario but, as with any alliance, there’s some uncertainty about whether—and how—that commitment would actually be fulfilled. The US and Japan don’t see eye-to-eye on every issue. The US has previously tried—unsuccessfully—to dissuade Prime Minister Abe from particular actions, such as the nationalisation of the Senkaku Islands and visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, that Beijing perceived as provocative. It’s quite possible that the US, wanting to avoid conflict with China, might provide only logistical support to Japan in a conflict over the Senkaku Islands. In America’s current Asia strategy, it seems the protection of the US–China relationship is a higher priority than the protection of the international order and status quo. As Secretary of State Kerry said, ‘there is no U.S. strategy to try to push back against or be in conflict with China’—hardly a reassuring talking point for US allies facing an aggressive China.

If the US decided not to fight alongside Japan over the Senkakus, there’s little doubt that Australia would also sit on the sidelines. Australia’s defence relationship with Japan should be guided not by a sense of democratic affinity or disdain for China’s repressive political system, but by our national interest. Some might argue that if US allies stick together, then the US will be more inclined to support them. That’s possible. Alternatively, the US might decide that regional countries can balance China without direct US assistance. That’s true for Europe and Russia, but not for Asia and China. But given America’s current war-weariness and a growing resentment of ‘free-riding’ allies, the possibility can’t be discounted.

Under different circumstances, I’d support a closer relationship between Australia and Japan. If Chinese aggression continues to escalate, and if America fully commits to using diplomatic and military means to coerce China into accepting an international society governed by rules and laws, then even a military alliance between Australia and Japan might be wise. But under current conditions, and without greater demonstration of American commitment, there’s no compelling reason for the development of even closer defence ties with Japan.

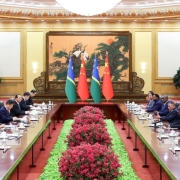

Iain Henry, a Fulbright Scholar, is a visiting PhD student at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. His research focuses on perceptions of reliability within alliances in the Asian region. He tweets at @IainDHenry. Image courtesy of Twitter user @JohnKerry.