The rise of China—a view from Singapore

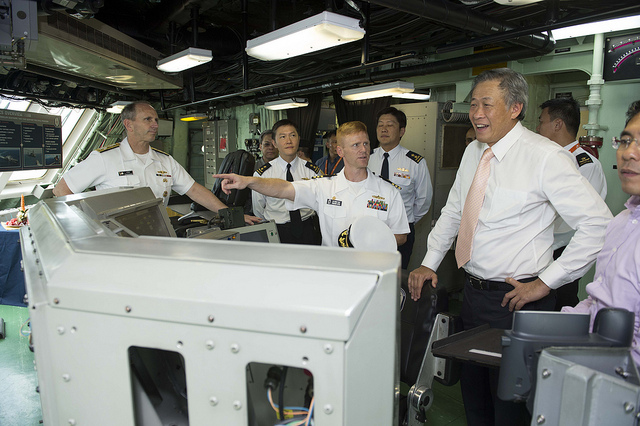

Australia’s regional foreign policy seems to have recently veered in the direction of closer support for Japan and away from a more neutral approach to the rise of China—presumably the result of a yet unannounced shift on the part of the Abbott Government. This has been the subject of a fair bit of debate, including an excellent piece by Robert Ayson here on The Strategist and by Hugh White in the Fairfax media the next day. To test the views of another country with a strong interest in the north Asia dynamic, I recently had the opportunity to speak at length to Singapore’s impressive Defence Minister, Dr Ng Eng Hen, to find that he and his Government have a far more nuanced view of the situation than that expressed by many Australian politicians.

Firstly, he explained that the rise of China is a simple fact and that the country is now a global power whose size, aspirations and strength needs to be accommodated and that everyone is going to have to adjust to this new reality. Despite having a very close military relationship with the US—particularly after a 1990 basing agreement—Singapore sees absolutely no need to chose sides over matters such as regional territorial disputes. When pushed on what appears to be Beijing’s aggressive style, he declined to do any finger pointing, instead saying that issues of territoriality in places such as the South China Sea involve a number of parties. Additionally, he took the view that Asia in particular owes China a debt of economic gratitude for saving the region from the worst effects of the global financial crisis.

In this way, Singapore is able to play a constructive role in regional affairs, especially through the influential forum the Shangri-La dialogue. This was a 2002 Singaporean initiative and has become an extremely useful forum, where parties are able to meet and exchange views publicly—but also more importantly in absolute privacy. By declining to pick sides, Singapore is in the enviable position of being seen as a regional honest broker and seemingly has no difficulty balancing this with close relations with both Washington and Beijing.

Even regarding China’s declaration in November of an expanded Air Defence Identification Zone—which was strongly criticised by Australia—Singapore chose to stay out of it. The position of Dr Ng is that many countries have ADIZs and that they are defensive in nature. Contrast that with Australia’s rapid jumping onto the Japanese bandwagon.

The different approach now being taken by Australia might be explained by the fact that many members of the incoming Abbott Government have a clear fondness for the policies of the Howard years, including for foreign affairs. After 9/11 and the War on Terror, the doctrine of the Bush administration was crystal clear—you are either ‘with us or against us’. The line being pushed by Washington was that no one could remain neutral in the ongoing struggle—and of course Australia enthusiastically signed up. In that situation the choice was seen as a very simple one: basically one between Goodies v Baddies.

To apparently apply the same simple rules to the rise of China might not be the most productive way to go. This is especially the case if at some future point the US is no longer interested in providing an overarching security umbrella. After all, there was a time in Australia’s not-too-distant past when senior political and military leaders had convinced themselves that as part of the British Empire we would always be protected by a larger power. When Britain had to choose between this region and a threat much closer to home, it didn’t take policymakers in London very long to figure out where their true interests lay. This is certainly a lesson that Singapore has not forgotten.

Kym Bergmann is the editor of Asia Pacific Defence Reporter and Defence Review Asia. His full interview with Dr Ng can be read here. Image courtesy of Flickr user US Pacific Fleet.