The forthcoming ASEAN CT summit

This weekend Malcolm Turnbull will host the leaders of the ASEAN countries attending the ASEAN–Australia Special Summit. The summit draws from the 2016 Defence White Paper and the 2017 foreign policy white paper, both which underlined the importance of ASEAN and the Indo-Pacific region to Australia’s security and prosperity.

Southeast Asia is the key to the Indo-Pacific because it links the Pacific to the Indian Ocean and straddles the world’s busiest trade route. This strategic geography explains the government’s aspirations for closer, broader Australia–ASEAN relations (see for example Graeme Dobell’s advocacy for Australia becoming a full member of ASEAN).

The special summit will include two sub-summits: a business summit and a counterterrorism (CT) summit. The goal of the former is to capitalise on the massive economic growth that ASEAN countries have experienced over the past few years by enhancing business relations between Australia and the ASEAN region. The region is home to more than 600 million people with a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion, and ASEAN economies have been growing at an average rate of 4.6% per year.

The CT summit, which—disappointingly but unsurprisingly—will only be open to officials, is meant to build on the 2016 ASEAN–Australia Joint Declaration for Cooperation to Combat International Terrorism. Its declared goal is ‘enhancing regional connectivity and cooperation to combat terrorism and violent extremism’.

Clearly, Marawi was a game changer. That a small band of dedicated Islamists was able to take over the city and withstand the Philippines army’s assault underlined the potential for Marawi to become ‘the region’s Raqqa’. There was also evidence of Islamic State (IS) financing.

It’s important, however, to put the Marawi battle in context and to recognise that what appears to have sparked the conflict had more to do with local politics and the approach adopted by President Rodrigo Duterte. This has led to questions regarding IS involvement in igniting the insurgency.

There are justified concerns about violent extremism taking root in the region and in Australia, but before adopting security measures that could substantially undermine basic human rights, such as Indonesia’s draft CT law, there’s a need to define and properly assess the threat.

First, it’s estimated that up to 1,000 people from Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines travelled to the Middle East to join IS. This compares with the EU, which has a combined population of more than 300 million—about half of Southeast Asia’s population—yet saw more than 5,000 of its citizens travel abroad to join IS.

Second, democracy is in decline in the Indo-Pacific, civil–military relations are uncertain and authoritarian regimes pervade the region. This means that there’s a need for caution in supporting CT practices across the region. That’s because human rights issues aren’t always on the minds of regional policymakers, who may use the threat of terrorism to suppress dissent.

Indonesia’s newly established National Cyber and Encryption Agency (BSSN) is a case in point. The agency’s budget is unknown and its statutory power isn’t clear. The agency reports directly to the president and is empowered to wage war on cybercrime, online radicalisation and fake news. That gives it considerable powers that could potentially be used to suppress civil society activities.

Third, several of the CT initiatives adopted by ASEAN member states are weak if not illusory: they may sound attractive, but their implementation moves at a snail’s pace. There’s a history of mistrust between many of the states, which makes cooperation—particularly in the security field—problematic.

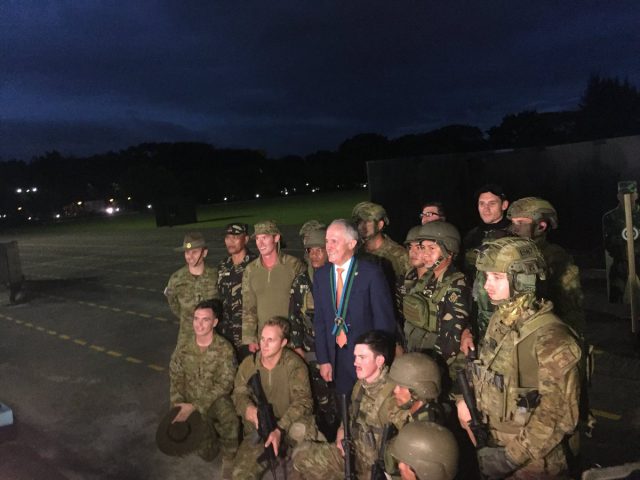

Since the battle for Marawi and the demise of IS, concern over terrorism has remained high in Australia and across Southeast Asia. At the June 2017 trilateral meeting on security between the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, ministers agreed to step up CT intelligence and information sharing and adopt further measures to curb terrorist financing.

There’s evidence that IS is seeking to establish a presence in our region. In the post-caliphate period, IS is likely to do that through online platforms and virtual planning. It’s notable that Southeast Asia now has the world’s third-largest population of internet users. Southeast Asians spend more time than anyone else on the mobile internet. Thais, for example, spend around 4.2 hours per day on the web, and Indonesians 3.9 hours, whereas Britons spend 1.9 hours.

Nevertheless, by blocking internet usage or adopting more aggressive security measures, the ASEAN member states aren’t really addressing the factors that breed violent extremism. We’re missing key motivators, which are increasingly linked to socio-economic and political disillusionment. It’s notable that the ASEAN countries (and Australia) have done little to stop the Myanmar government’s actions against the Rohingya, which some Islamists have highlighted in their calls for action.

The CT summit is an opportunity for Australia to not only enhance its security relationship with its ASEAN neighbours, but to make sure that new CT measures are consistent with basic human rights and dignity. Security is important, but we must remember that political oppression, social dislocation and economic insecurity spur violent extremism.