The bomb for Australia? (Part 1)

In this three-part series, I examine the counter-arguments that proponents of Australia obtaining nuclear weapons need to address before the nation contemplates such a move.

A heavyweight trio of Australia’s strategic and defence policy analysts has opened a debate on the possibility of Australia acquiring nuclear weapons. Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith documented the increased strategic risk to Australia based on a critical assessment of China’s capabilities, motives and intent.

Paul took that further in The Australian, canvassing the idea of investing in capabilities that would reduce the lead time for getting the bomb to give us more options for dealing with growing strategic uncertainty. North Korea’s nuclear advances and diminishing confidence in the dependability of US extended nuclear deterrence add to the sense of strategic unease.

Andrew Davies inferred Hugh White’s support for the idea and implied that both Paul and Hugh had been too coy to take their analyses to the logical conclusion. Hugh has been the preeminent Australian analyst advocating an independent recalibration of our position vis‑à‑vis the China–US tussle for strategic primacy in the Asia–Pacific.

In reply, Hugh politely, gently but firmly rejected the implication that he’s a closet supporter of Australia taking the nuclear weapon path. He neither advocates nor predicts that Australia should or will go nuclear. He professes uncertainty about the role of nuclear weapons in shaping Asia’s emerging strategic landscape, highlights the importance of getting the decisions right on conventional capabilities first, and points to the choices and trade-offs that would then have to be made between the security benefits and risks of a weaponised nuclear capability.

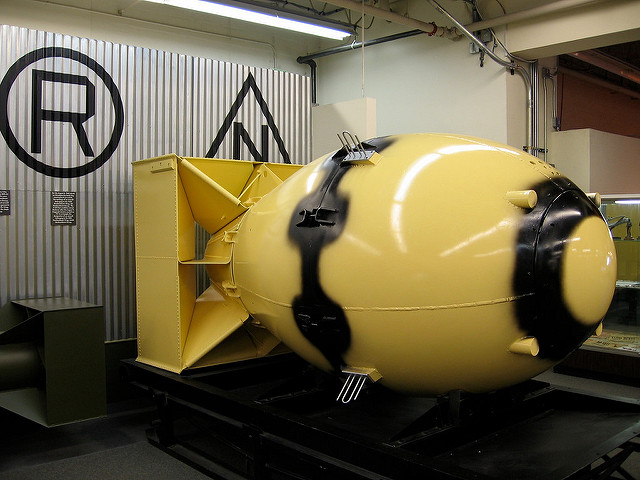

Who will call out the nuclear emperor for being naked? Nuclear weapons haven’t been used since 1945—Hiroshima was the first time and Nagasaki the last. Their very destructiveness makes them qualitatively different in political and moral terms, to the point of rendering them unusable. A calculated use of the bomb is less likely than one resulting from system malfunction, faulty information or rogue launch.

On the other hand, the non-trivial risks of inadvertent use mean that the world’s very existence is hostage to indefinite continuance of the same good fortune that has ensured no use since 1945.

Curiously, Hugh, Paul and Andrew don’t explore the roles that nuclear weapons might play, the functions they would perform, and the circumstances and conditions in which those roles and functions would prove effective. This is a crucial omission. The arguments I canvassed in a review of the illusory gains and lasting insecurities of India’s nuclear weapon acquisition apply with equal force to Australia, albeit with appropriate modifications for our circumstances.

In short, the nuclear equation just does not compute for Australia.

Consistent with the moral taint associated with the bomb, the most common justification for getting or keeping nuclear weapons isn’t that we’d want to use them against anyone else. We’d only want them either to avert nuclear blackmail or to deter an attack. Neither of those arguments holds up against the historical record or in logic.

The belief in the coercive utility of nuclear weapons is widely internalised, owing in no small measure to Japan’s surrender immediately after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet the evidence is surprisingly clear that the close chronology is a coincidence. In Japanese decision-makers’ minds, the decisive factor in their unconditional surrender was the entry of the Soviet Union into the Pacific war against Japan’s essentially undefended northern approaches, and the fear that the Soviets would be the occupying power unless Japan surrendered to the US first. Hiroshima was bombed on 6 August 1945, Nagasaki on 9 August. Moscow broke its neutrality pact to attack Japan on 9 August and Tokyo announced the surrender on 15 August.

There’s been no clear-cut instance since then of a non-nuclear state having been bullied into changing its behaviour by the overt or implicit threat of being bombed by nuclear weapons.

The normative taboo against the most indiscriminately inhumane weapon ever invented is so comprehensive and robust that under no conceivable circumstances will its use against a non-nuclear state compensate for the political costs. That’s why nuclear powers have accepted defeat at the hands of non-nuclear states (for example, Vietnam and Afghanistan) rather than escalate armed conflict to the nuclear level. Non-nuclear Argentina even invaded the Falkland Islands in 1982 despite Britain’s nuclear arsenal.

Australia’s nuclear breakout would also guarantee the collapse of the NPT order and lead to a cascade of proliferation. Each additional entrant into the nuclear club multiplies the risk of inadvertent war geometrically. That threat would vastly exceed the dubious and marginal security gains of possession. The contemporary risks of proliferation to, and use by, irresponsible states in volatile conflict-prone regions, or even by suicide terrorists, outweigh realistic security benefits. A more rational and prudent approach to reducing nuclear risks to Australia would be to actively advocate and pursue the minimisation, reduction and elimination agendas for the short, medium and long terms identified in the Report of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament—an Australian initiative that was co-chaired by distinguished former Australian and Japanese foreign ministers.