The Abbott strategic trifecta (2): Japan as ‘strong ally’

According to Tony Abbott, Japan is Australia’s ‘best friend in Asia’ and a ‘strong ally’ . These are important elements of what this series calls the strategic trifecta—alliance, interests and values—which the Prime Minister has invoked in placing Australia beside Japan and the US in the East China Sea confrontation with China.

In elevating Japan to ‘strong ally’, Abbott is adding to what John Howard built when he created a strategic partnership with Japan and put the trilateral leg into the US–Japan and the US–Australia alliances.

This column seconds Robert Ayson’s view that Abbott’s words take the Australia–Japan relationship to a new level:

Earlier this year, when the Gillard Government’s White Paper was published, we read that the ‘defence and strategic partnership between Australia and Japan has been strengthened in recent years’. An almost instant relic, the Gillard era document also made an early reference to ‘Japan, a US ally’. We will need to watch carefully to see whether Mr Abbott’s comments have changed the logarithm to ‘Japan, a US and Australian ally.’ Certainly the new government’s approach to Japan has treated it as if it were at the very least an informal ally deserving Australia’s unstinting support.

The nature of hackdom is to immediately ask questions, so where should we locate some hesitancies or uncertainties in this new concept of Australia as a strong-staunch-stout-ally of Japan?

If Australia is a ‘strong ally’ of the US and equally in Abbott’s words, a ‘strong ally’ of Japan, what’s the difference between the levels of ‘strongness’ of the two alliances? The unwavering, almost automatic loyalty that Australia has given the US for 70 years doesn’t transfer to this new ally. To further complicate the equation, what will Australia do for its strong ally Japan that it won’t do for its ‘strategic partner’ China? Bear in mind that this strategic partnership with China was given formal expression only in April along with the prize of an annual bilateral China–Australia summit. ’Strategic partnership’ has joined ‘relationship’ as one of those international relations terms that can conceal as much as it explains—Beijing has been teasing and tempting Canberra with the strategic partnership lure for years.

‘Japan alliance’ presumably trumps ‘China strategic partnership’, yet the complications keep on compounding as these relationships are related to ’interests and values’ in Abbott’s trifecta (which will be the topics of the next two columns).

In seeking hesitancies or uncertainties, mark intelligence as one area where the level of ‘strongness’ will tend to the scrawny. I always defer to the ever-reliable Derek Woolner, but both eyebrows lifted when he mused here last week that future revelations from National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden might ‘create an impression that the Five Eyes intelligence community is actually a regional eight (Japan, Singapore and South Korea colluding with the members of the Anglosphere)…’

Such an impression would underestimate the culture, history and tightness of the Five Eyes system that connects the US, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. And putting Japan and South Korea in the same sentence as the term ‘intelligence community’ takes you immediately to the venom that bedevils dealings between Seoul and Tokyo.

Plenty of intelligence gets shared between Australia, Japan and the US. But this doesn’t equate to full membership of the Five Eyes family. In support of this assertion, consider the judgement of Joel F. Brenner, who has sat in the top echelons of US intelligence, dismissing the idea of widening the circle of allies in the Five Eyes club:

The Five Eyes nations share a common language, common legal traditions, and united wartime experiences. They also work side-by-side in in one another’s agencies. These arrangements have no parallel and are based on a century of deep trust and experience. It is unrealistic to imagine that Germany and France would suddenly be admitted to the club.

If Germany and France can’t make it to full club membership, then neither can Japan. The reference to deep trust and experience brings us to a lot of history between Australia and Japan. Australia knows plenty about Japan but strategic trust is a relatively recent arrival. For more than half of Australia’s first century as a nation, Japan dominated Australia’s military nightmares (even during WWI when Japan was a British ally). The creation of ANZUS as the formal express of the US alliance was as treaty-level reassurance that the Japan terror would never return.

The moment when Australia started to have the confidence to express some levels of strategic trust in Japan arrived during the Fraser Coalition and the Hawke Labor governments. Both governments expressed their backing for the idea that Japan had earned the right to become a permanent member of the UN Security Council. If this moment of confidence is placed around 1980, that means Australia has shifted over three decades from strategic confidence through strategic partnership to the Abbot moment of alliance.

Abbott will certainly have lots of pain from China over that ally comment. Nearly as interestingly, however, he might have some work to convince his own electorate, especially when the next leg of the trifecta—interests—steps onto the paddock. It’s quite a change in the Japan narrative as presented to Australians: from the number one economic partner with the peace constitution to the number two economic partner that has become an ally.

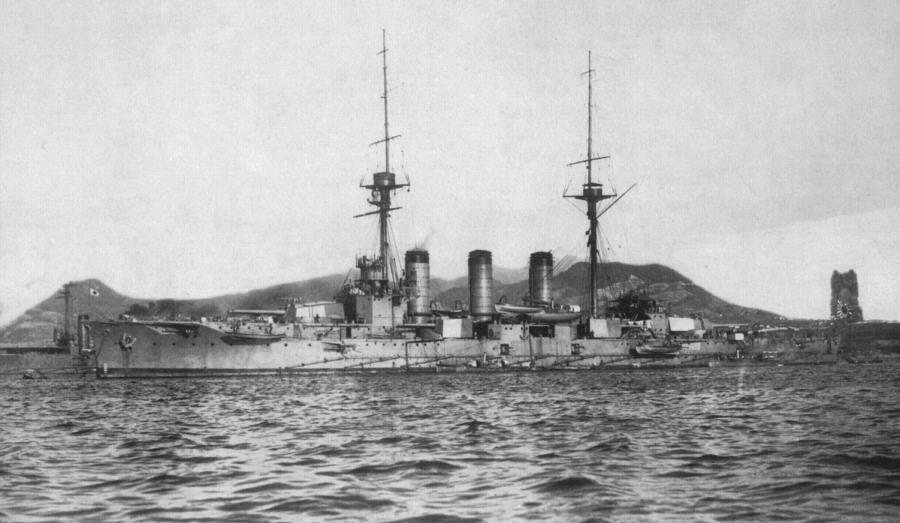

Graeme Dobell is the ASPI journalist fellow. Image via Wikimedia Commons.