#StopAsianHate: Chinese diaspora targeted by CCP disinformation campaign

Chinese diaspora communities continue to be an ‘essential target’ of Chinese-state-linked social media manipulation taking place around the world. Chinese-state-linked accounts are running a multilingual, cross-platform campaign aimed at stoking the fears of these communities by drawing false equivalences between anti-Asian racism and increased speculation about Covid-19 laboratory-leak theories. This campaign illustrates the Chinese Communist Party’s common tactic of using accusations of racism to deflect criticism.

The #StopAsianHate hashtag was started by Asian-Americans in March in an effort to end racially motivated attacks and discrimination. It has been trending ever since. There’s no doubt that this hashtag represents a legitimate movement to raise awareness of the issue of anti-Asian violence. The Covid-19 pandemic has seen a rise in anti-Asian violence, both in Australia and internationally. One of the most prominent incidents was the deadly shooting of six Asian-American women in an Atlanta spa, which is being investigated as a hate crime.

However, the fast-changing nature of social media makes even legitimate online movements vulnerable to co-option. The same hashtag is now being used to smear Hong Kong doctor Li-Meng Yan, who has published three controversial articles claiming that the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 was artificially created in a Chinese laboratory.

Yan’s case is complicated. Her claims have been widely criticised as misleading, and Harvard social media researchers have described her work as an example of ‘cloaked science’ intended to manipulate the media. At the same time, prominent US right-wing figures have been amplifying her claims, including Republican strategist Stephen Bannon and Chinese dissident Guo Wengui, who has been targeted in the past by Chinese state information operations but also leads his own sprawling network peddling disinformation.

A search of the hashtags #StopAsianHate and #LiMengYan on Twitter between April and June 2021 returns over 30,000 tweets and retweets from more than 6,000 suspicious accounts. All posted the same set of hashtags, memes, English phrases (such as ‘Stop Asian discrimination’, ‘Yan limeng is rumor led to discrimination against Asian Americans’ and ‘Let Yan limeng disappear from America’) and Mandarin phrases (such as ‘闫丽梦公开承认“亚裔歧视”是由于其造谣病毒来源于中国实验室而引发的!’, which roughly translates as ‘Yan Limeng publicly admitted that “Asian discrimination” was caused by the rumor that the virus originated from a Chinese laboratory!’).

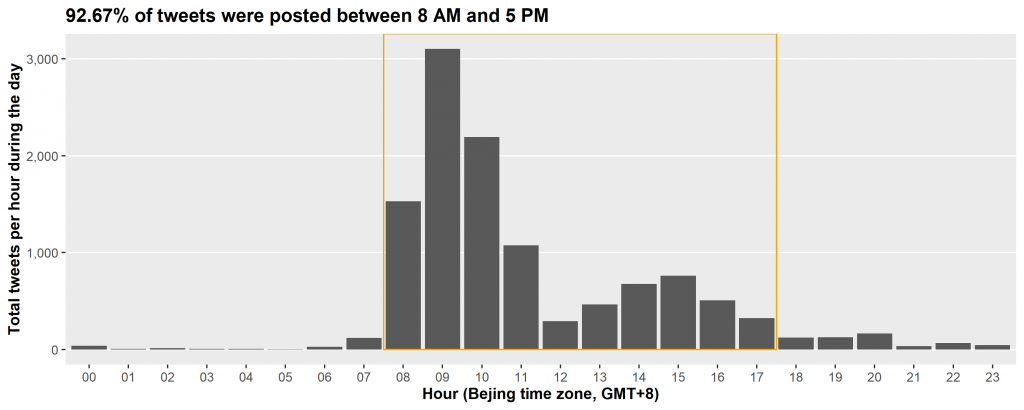

While accounts espousing a variety of different ideologies have amplified these hashtags, several features of this network suggest that these accounts are being operated by actors based in the People’s Republic of China, where Twitter is banned. For example, posting patterns for these accounts neatly match Beijing business hours.

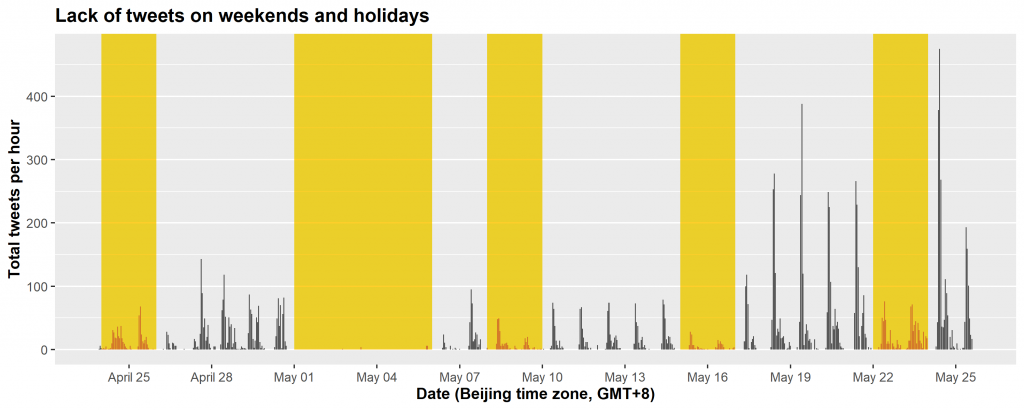

In addition, there was less campaign activity on weekends and almost none during the Chinese national Labor Day holiday from 1 to 5 May.

Similar behavioural features were observed in a 2020 Twitter-attributed Chinese state takedown dataset.

Like other Chinese-state-linked information operations, the campaign has worked across multiple US-based platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Reddit, Google Groups and Medium. Images and phrases used in the campaign have also appeared on non-US-based platforms such as TikTok, VK and a Russian amateur blog site.

The extent of posting on new multi-language platforms indicates a marked development in capability and coordination. And the use of racism suggests efforts to leverage issues that the targeted audience is already emotionally engaging with. After rallies were held by Asian diaspora communities in March 2021 against racially motivated attacks, posts in this disinformation campaign called for similar real-world demonstrations at Guo’s residence in New York City to ‘Protect Grandma’, a reference to a 76-year-old Chinese grandmother who fended off an unprovoked assault. It’s unclear whether these Guo-targeted demonstrations happened.

President Xi Jinping has highlighted the importance of the Chinese diaspora as part of fulfilling the ‘China dream’. China’s top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, has similarly written that maintaining the support and sentiment of these communities and countering perceived threats are a ‘pressing need’ for the CCP. Even if lab-origin theories remain unsubstantiated, a belief that Beijing might have withheld evidence of a lab leak would threaten the CCP’s standing abroad and could influence domestic opinions in China.

If the goal of this new social media campaign is to deny these lab-leak theories, or to convince audiences that rising anti-Asian violence is due to Yan and her alleged co-conspirators Guo and Bannon, then this network is not particularly sophisticated, or convincing. Alternatively, by criticising the trio’s efforts to spread narratives about the origins of Covid-19, the network may be deliberately amplifying Yan’s claims and drawing attention away from more informed and balanced voices. This would benefit Beijing’s interests by associating lab-origin theories with fringe conspiracy theorists and undermining these hypotheses among mainstream audiences.

The origin of Covid-19 is a highly politicised issue for the Chinese government, and the state’s propaganda apparatus is deploying its full suite of statecraft to influence international opinion on the matter. Chinese diplomats and state media have overtly pushed conspiracies that Covid-19 originated in the US, and these claims have been amplified on social media by patriotic individuals and inauthentic accounts.

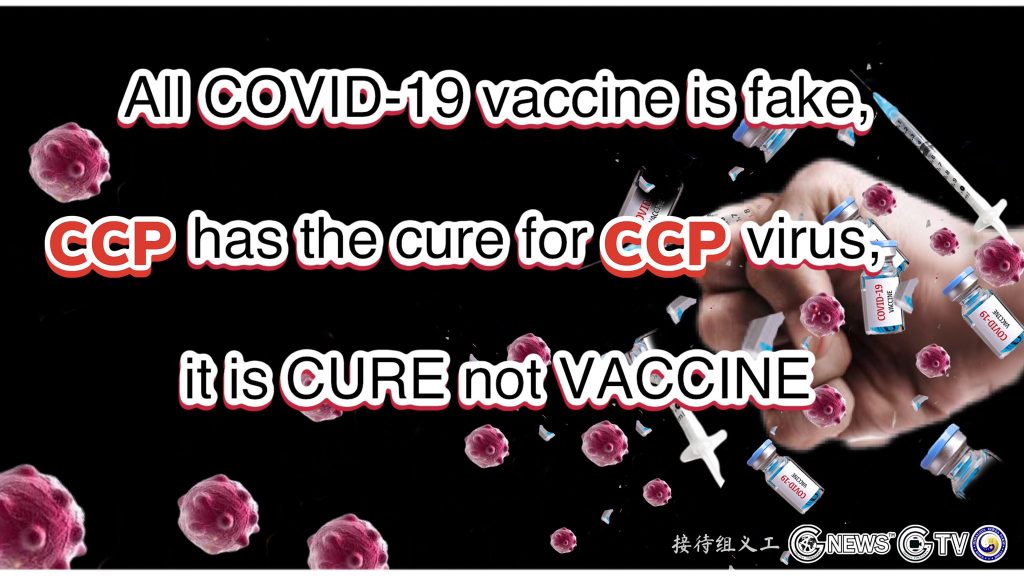

Removing inauthentic Chinese-state-linked assets from social media platforms may limit the reach and impact of CCP propaganda, but these disinformation campaigns have proved to be highly resilient in terms of their capacity to maintain a consistent presence on mainstream US-based platforms. The lack of accessible and credible Chinese-language information on US-based social media networks leaves a vacuum that disinformation can fill. For example, searching for #LiMengYan and #UnrestrictedBioweapon on Twitter between April and June 2021 also returned a separate anti-vaccine and anti-CCP campaign targeting Chinese diaspora run by accounts that could be linked to Guo, based on his logos ‘GNews’ and ‘GTV’ appearing on images.

In Australia, the Senate Committee for Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade published a list of recommendations in February to support diaspora communities, including reviewing the government’s approach to communicating essential information to those communities. The government should consider developing initiatives to contest disinformation and establish forums for consultation with community leaders as part of a broader strategy to tackle foreign interference.

Previous ASPI research recommended greater funding for Chinese-language media in Australia to provide alternatives to Chinese-state-influenced media outlets and the highly controlled WeChat messaging app. New funding and support could facilitate partnerships between Chinese-language factcheckers at national broadcasters with budding Chinese community media.

Chinese diaspora communities find themselves caught between increasingly well-resourced CCP propaganda and disinformation campaigns and the spectre of systemic racism that still looms large in their host countries. One of the ongoing challenges for all governments around the world will be finding ways to protect and support Asian communities from the concurrent threats posed by entrenched racism and foreign interference.