South Korea seeks closer strategic links with Australia

Little noticed publicly in either Australia or South Korea, Seoul has taken steps in recent months that suggest intent to forge closer strategic links with Canberra. The trend has accelerated under Korea’s new administration and should be factored in to Australia’s defence strategic review as an opportunity to strengthen our regional security and economic relationships.

During the June NATO summit attended by President Yoon Seok-yeol (who met with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese), Korean Prime Minister Han Duck-soo reportedly said: ‘Our priorities in values and national interests are changing’ and ‘I am not convinced that we are going to be affected much by China’s complaints.’

China’s demands irk Korea. Recognising Chinese power, proximity and major trade and investment interests, Korea will think hard before offending it, evidenced by Yoon—clumsily—not meeting US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in person in Seoul following her visit to Taiwan. And Korea will also not formally join the Quad, although Seoul is positive towards both it and possible cooperation with AUKUS.

But China’s recent aggressive military exercising and demands to limit operations of a US THAAD anti-missile battery in Korea (which, on its deployment in 2016, provoked tough Chinese economic sanctions) will strengthen already high levels of anti-China sentiment in Korea. It may lead to toughening of Seoul’s Indo-Pacific policy and greater willingness to engage substantively with Western powers and others concerned by the risks in China’s actions.

Like Australia, Korea faces a darkening geoeconomic and strategic outlook. Policymakers in the new Yoon administration will be weighing:

- renewed belligerence by North Korea, with resumption of nuclear testing considered imminent, perhaps aimed at development of tactical nuclear weapons

- sharpened US–China strategic competition, with growing possibilities for miscalculation and pressures on Seoul to abandon its policy of ‘strategic ambiguity’

- concerns that any military action in the region will disrupt Korea’s sea lines of communication and could cripple its economy

- related concerns that a resumption of Chinese economic coercion could include China throttling exports of rare earths and other critical minerals to Korea’s critical semiconductor industry

- fears that America’s (and Europe’s) preoccupation with the Ukraine war will weaken their attention to East Asian challenges, a view given more substance by Washington offering no new market access under its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

- widely shared worries about a return of Donald Trump—or a Trumpian figure—to the White House in 2024, again undermining confidence in Korea’s US alliance, and ‘America first’ policies that weaken the US commitment to a robust Indo-Pacific posture

- Korea’s inability fully to surmount its historical differences with Japan, bolstered by Japanese frustrations with Korean policy, which continues to truncate critical trilateral US–Japan–Korea defence and intelligence cooperation.

In short, Korea, like Japan, feels increasingly vulnerable and faces multiple challenges to its interests. But Korea is not sitting idle. It is building its already significant defence manufacturing industry—now a major export earner—to encompass not only ground force equipment but space, cyber, longer-range ballistic missiles, ballistic missile submarines, drones, fighter aircraft and a light aircraft carrier.

These capabilities help address the growing North Korean nuclear and conventional threat, and in particular respond to the North’s apparent effort to develop a battlefield nuclear weapon, an indication that the North hasn’t given up ambitions to blackmail the South, if not force a reunification on the North’s terms.

And the defence build-up goes well beyond that, enabling Seoul to play a much larger regional security role. The posture involves development of means to project power well beyond the Korean peninsula and to enhance deterrence against a more assertive China, even if the US alliance weakens. Korea has a long historical memory.

So where does Australia fit in? Australia has been a key member of the United Nations Command for Korea since the Korean War, and although this commitment has been small, it has been consistent. After the central US role, Australia’s probably the most significant. It has provided the basis for annual exercising with both countries in South Korea and a window into contingency warfighting and evacuation planning.

Until now, though highly valued by the US, the Australian commitment hasn’t been similarly valued by the myopic Korean military. But, driven by Yoon’s initial foreign policy advisers who have strong links with Australia, and a deteriorating regional and global security outlook, this view may be changing.

Aside from the common interests of the two countries, Korea eyes a potential significant defence market. Korea’s Hanwha Defence is building K9 self-propelled howitzers for the Australian Army in Geelong, and is bidding for the major contract to replace the army’s infantry fighting vehicles with a vehicle designed to meet Australian conditions. If it wins the contract, defence links could become much stronger.

But Korea, short of key resources, is also looking to Australia for secure supplies of hydrogen as it transitions from a fossil-fuel-dependent economy and away from Australian-supplied coal and liquefied natural gas. Australian rare earths and critical minerals will help reduce Korea’s vulnerability if China reimposes economic sanctions on Korea.

Hence outgoing President Moon Jae-in’s unexpected visit to Australia at the end of his term last November to engage potential suppliers and investors, particularly for critical minerals. A big resources trade delegation quickly followed in March, and an Australia–Korea Business Council delegation, focused specifically on these priorities, was welcomed in Korea in June.

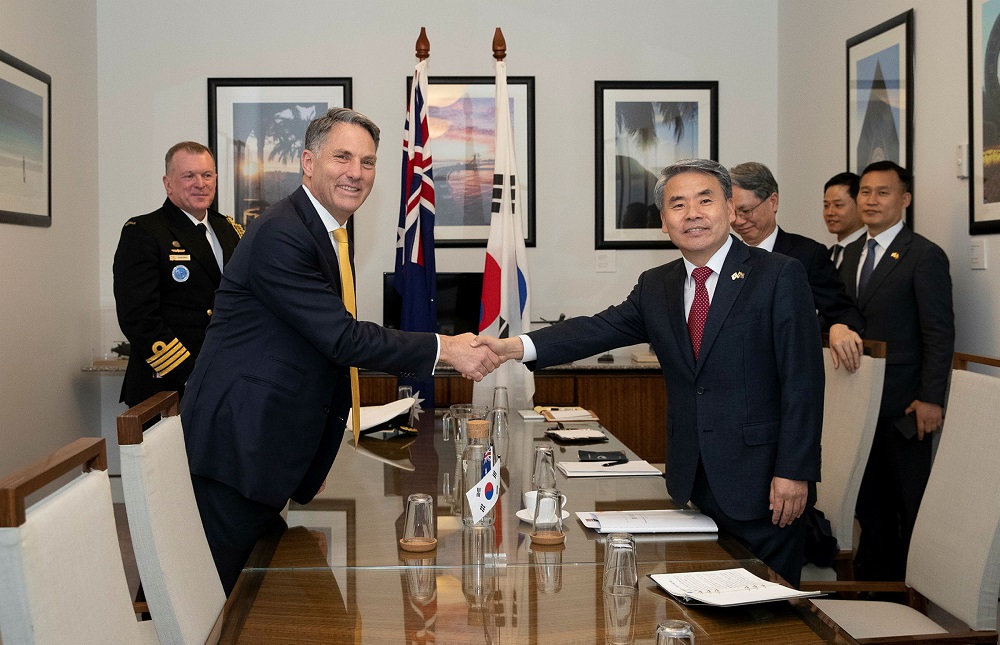

In turn, this was followed in July by a visit from Korea’s minister for defence acquisition, Eom Dongwhan, accompanied by a delegation from key defence manufacturers. Only three weeks later, in early August, Korea’s defence minister, Lee Jong-sup, visited both Canberra and Hanwha’s new Geelong plant, meeting with Australia’s defence minister, Richard Marles. These visits came early in the life of both new governments, indicating priority on both sides. The visits were not part of the routine structure of consultations between defence and foreign ministers, suggesting a wish to quickly build stronger defence links—and for Korea to promote its defence exports.

Australia’s defence strategic review should look closely at this pattern. Korea has a sophisticated defence industry, while its strategic priorities align increasingly closely with Australia’s. Until now, the opportunities in this new alignment have largely been overlooked—by both countries—but growing regional tensions suggest a rethink is timely.