Solomon Islands and Kiribati switching sides isn’t just about Taiwan

Kiribati and Solomon Islands switching diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China is about more than the Chinese Communist Party’s relentless campaign to isolate Taiwan. Certainly, it’s important to PRC President Xi Jinping to undercut the 24-million-strong democracy that is Taiwan—because it represents a vibrant alternative model of governing the 1.4 billion people under CCP rule, and because further isolating Taiwan from the international community is part of his own ‘maximum pressure’ campaign that he mistakenly seems to believe will push the people of Taiwan towards merging with mainland China.

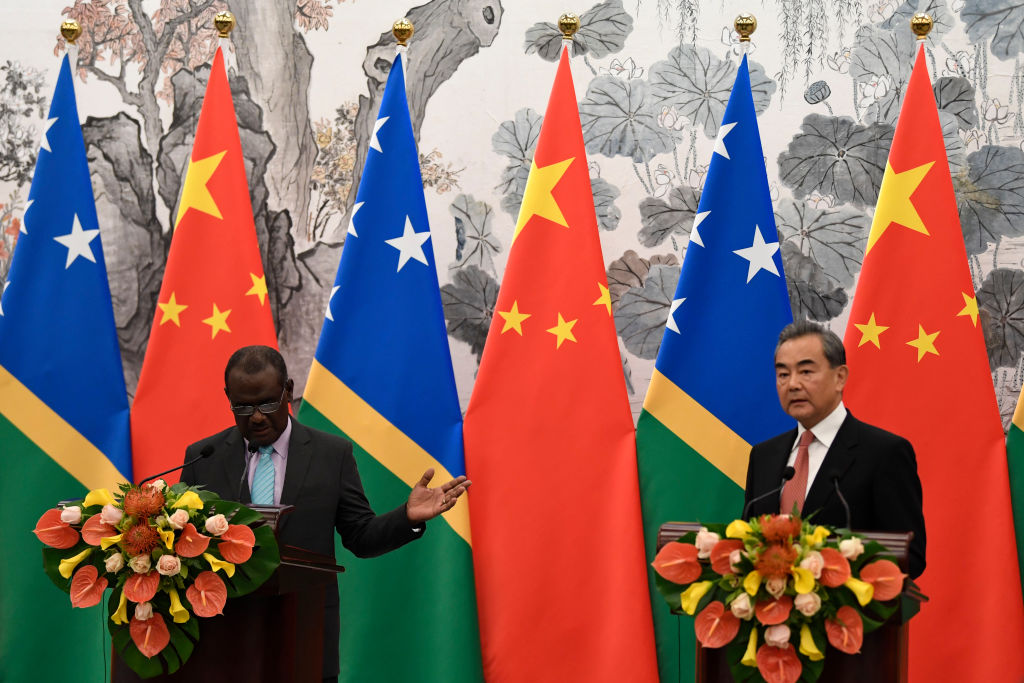

But we’ve put too much attention on the tussle for diplomatic recognition in the South Pacific and not enough on understanding Xi’s other motivations for spending $730 million on buying the Solomons’ change of mind and promising a sum to Kiribati that’s icing on this eyewatering amount.

What else is Xi buying with his money and promises of mutual respect? Here’s the iceberg of interests behind the cash and the flag-recognition switch.

Xi’s China Dream is about remaking China’s place in the world, and that means changing the system of international governance to be more accepting of his authoritarian model of rule (as the European Commission noticed in March this year when it stated that the Chinese state posed a systemic risk to the liberal democratic system of governance operated by the EU and by the broad set of international institutions).

Collecting more UN votes from small island governments supping on loose Chinese money helps here—and it’s pretty cheap buying. It means more chances to frustrate others’ agendas at the UN, more supportive voices for Chinese initiatives, and a greater ability to vote down unpleasant reporting or resolutions critical of the one-party state.

This can help across a range of issues that the Solomons and Kiribati are probably not at the front of mind on—like cyber norms and space treaty proposals. Fortunately, the leaders of Kiribati and the Solomons are representatives of their societies, so they are almost certainly not about to join in various nonsensically supportive statements about how well Xi’s security apparatus is treating the 13 million citizens in Xinjiang as it engages in cultural genocide there.

The switch of allegiance and the money also buy symbolism and provide opportunities for military engagement and presence. They send a message about rising and falling influence beyond the Taipei–Beijing tango. They say Australia’s Pacific step-up hasn’t yet stepped up enough—Beijing is still acting to increase its influence. All the diplomatic noises from Canberra about this being a sovereign matter for Honiara and Tarawa can’t hide the fact that it’s a loss for Canberra in the region as well as for its Taiwanese friend and partner.

For the United States, the reversal is bad news too, given the pressure no doubt also on the Marshall Islands and Palau, both of which still recognise Taiwan. As the RAND Corporation has noted, these states and their maritime territories are ‘a power projection superhighway running through the heart of the North Pacific into Asia [that] effectively connects US military forces in Hawaii to those in theater, particularly to forward operating positions on the US territory of Guam’.

The biggest issue, though, is below the surface—literally. Xi’s cash splash is about what the South Pacific has in abundance and what his China Dream is demanding: resources. Australia has been slow to wake up to more than the Chinese state’s broad influence-building in our near region. We’ve taken far too long to realise what Beijing already has. The massive exclusive economic zones of states like the Solomons and Kiribati are increasingly valuable sources of all kinds of resources, not just fish, but all the other plant and animal life in the water column, and all the natural resources on the sea floor and under the sea. There’s copper, gold, zinc, nickel, cobalt and magnesium, to give you the idea.

Small Pacific island states are future ‘blue economy’ resource-owning superpowers, and, as the recent Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ communiqué shows in its many references to the ‘Blue Pacific Continent’, they know it.

Beijing wants to be first in the queue for exploiting these riches to feed its growing economy, and it will want to shape South Pacific states’ underdeveloped frameworks for doing so. The risk is that Beijing’s interests in getting hold of these resources over the next decades will outweigh its desire to help South Pacific states manage them as responsible stewards. Think, for example, how Beijing prioritised building military facilities on reefs in the South China Sea over the cost of the mass destruction of marine ecosystems caused by China’s dredging and crushing of coral reefs as part of the bases’ construction.

The blue economy is the South Pacific’s path to prosperity and independence from foreign donors. But that prosperity will be short-lived if the water column and undersea riches are overexploited because those with the ability to access and harvest them prioritise their own consumption over the responsible management of fragile ecosystems.

So, what should Australian policymakers be thinking about when they look back over the past week or so?

On Taiwan, the lesson is that Beijing is working as hard and fast as it can to change the status quo, making it time for Australia and other international partners to reassess and deepen our own engagement with Taiwan. Given Xi’s actions, what do we want to change in the status quo?

Our interests with Taiwan include supporting it with its continuing Pacific island partners like Nauru, Palau and the Marshall Islands. But Taiwan is becoming much more valuable beyond this too—as a government and community on China’s doorstep that, like the people of Hong Kong, are on the front line in the global contest between digital authoritarians and democracies; as a high technology partner for Australia and the US in that contest; and as the owner of a large piece of strategic geography that complicates China’s projection of military power through the ‘first island chain’.

Australia needn’t change its formal policy on Taiwan to do a whole lot more. Canberra could simply take a leaf out of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s book. He didn’t change the overarching constitution to grow his ability to use the Japanese military; he just reinterpreted it and so changed policy underneath it.

One example is establishing direct working contacts between Australian and Taiwanese defence and national security agency officials. This makes sense for Australia now in the new environment of strategic competition between the US and the Chinese state because our Taiwanese colleagues know things about the Chinese state that we don’t, and we have insights for them too.

On a planet where all kinds of natural resources are under pressure from population growth and the effects of climate change and overexploitation, Australia needs to look way beyond its long-term focus on maritime surveillance and fisheries protection in our security, research and institutional engagement with our Pacific family on the blue economy.

Continued focus on fisheries, as ministers Marise Payne and Alex Hawke have shown recently, is essential. But it’s insufficient. Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama is ahead of the curve here and has proposed a 10-year moratorium on seabed mining in the South Pacific. He should have our support, but it will take much more than that.

Can you step up underwater?