Singapore after Lee Kuan Yew

The world’s media and international leaders have responded to the passing of Singapore’s former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew by recounting his eventful life and lauding his remarkable achievements. There is no need—or space—to enumerate them here; the coverage has been ample.

The world’s media and international leaders have responded to the passing of Singapore’s former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew by recounting his eventful life and lauding his remarkable achievements. There is no need—or space—to enumerate them here; the coverage has been ample.

I’ll focus on whether key elements of the Singapore he constructed, and which have served Singapore well in its rise, will suffice in meeting the challenges faced by the country now that his guiding hand is no longer there.

One can be reasonably confident that Singapore will continue to be an economic success story. The economy developed under his tutelage is diverse, with strengths in finance, electronics and information technology, pharmaceuticals, transport, select heavy industry, international education and tourism, a breadth of capabilities which equip it to weather pressures from abroad in any particular sector. Economic policy is in the hands of some very smart people in the economic ministries, central bank and regulatory authorities.

The most difficult economic pressures are likely to come from within. There has been growing resentment, among ordinary Singaporeans, about the sharp disparities of wealth that now characterise Singaporean society. They feel that the cake is not fairly distributed.

Exacerbating this has been the influx, in accordance with government policy, of a class of well-paid expatriate professionals with expertise deemed to be of value to the evolving economy. These expats are seen by many aspiring Singaporeans as a threat to their own job prospects.

Crucial to the economy has been the highly regulated importation of what can be legitimately described as an underclass of low and semi-skilled foreign workers, who keep the factories humming, the construction sector profitable, the landscaped city neat, and thousands of Singapore families comfortable through their service as domestic workers.

The pay rates and rights of this army of strictly temporary workers are significantly less than those of the rest of the workforce. While this does not appear to trouble most Singaporeans, their numbers, the resulting downward pressure on wage rates and the additional congestion in an already overcrowded island, suggest the current structure of the workforce is not sustainable over the longer term.

Singapore’s array of sovereign wealth funds and large government-linked companies, fostered by Lee and staffed at the top by favoured officials, dominate the commanding heights of the economy. There is questioning though about whether they crowd out true private enterprise.

The political structures erected by Lee will also be tested in coming years. Elections are conducted meticulously, which has enabled the Government to portray Singapore as a democracy. The media is largely government-owned and compliant, rendering the workings of government opaque and opposition voices neutered.

Lee Kuan Yew and other members of his leadership group have been quick to resort to defamation suits against political opponents, leading to predictable convictions, large fines, and even bankruptcy and ineligibility to run for political office. Everyone just knows that stepping out of line in such a small and tightly controlled society can affect your prospects in life.

For many years the populace have acquiesced in this authoritarian rule, in a tacit compact under which the ruling People’s Action Party, in return, provided law and order, increasing prosperity and a largely meritocratic system. All these are substantial benefits, but a more sophisticated electorate is now seeking more.

With Lee Kuan Yew’s demise, people will continue to be wary of criticising the ruling caste and its omniscient policymaking, but perhaps not so fearful. The emerging fissures on a range of economic and social problems, and on political reform, will require careful management.

Up till now the national leadership has made some modest if tardy responses to public concerns, and it will need to enhance its political skills if it is to maintain its position as demands inevitably grow for a more open and fair political system. Political will and ruthlessness in the employ of the instruments of state, as practised by Lee, will not be sufficient. And a tightening of control and a circling of the wagons by the ruling clique would be the wrong response at this time.

Singapore’s international standing will be affected by Lee Kuan Yew’s demise. Integral to its standing have been its economic strengths, its well-resourced (if untested) military, and its competent and disciplined policies in a whole range of areas. But crucial has been Lee Kuan Yew himself: his long experience in government, his astute understanding of regional and international affairs, and his willingness to offer hard-headed and incisive commentary.

Other international leaders, not least our own on occasions, have been beguiled by Lee. He has presented a contrast with certain other Asian leaders, some from countries more important than Singapore, who were not so eloquent in English or so coherent or persuasive.

Singapore’s current Prime Minister and Lee Kuan Yew’s son, Lee Hsien Loong, is an impressive interlocutor himself, but cannot have the stature of his father or inspire such awe. Lee’s aura will linger on though, and continue to influence perceptions of Singapore for a long time to come.

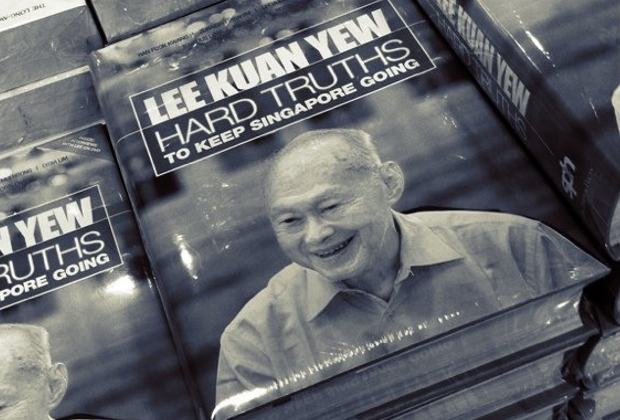

Miles Kupa served as Australia’s High Commissioner to Singapore from 2005 to 2008. Image courtesy of Flickr user chinnian.