Science, not fiction: modern batteries for modern submarines

When we expressed concern about the Royal Australian Navy’s plan to fit the first of its new Attack-class submarines with an outmoded lead–acid main battery system in over a decade’s time, former RAN submarine engineer Paul Greenfield rejected our key arguments.

There are a number of issues raised by Greenfield that we’d dispute. More importantly, it’s at the policy level that his critique should be rejected, and workable solutions should be developed to overcome the valid problems that he highlights.

Greenfield rejects the idea of fitting a light-metal main battery in the Attack class at this stage primarily because of his concerns about the danger to the crew of fire triggered by lithium-ion batteries. We believe those safety issues can be resolved.

He also raises the difficulty and risk involved in modifying a design already optimised for the older technology. Unfortunately, the speed of technological change precludes adherence to such a linear approach.

Four factors lead us to conclude that current planning is very likely to deliver a submarine that is obsolescent.

First, we aren’t discussing current levels of technology, practice and performance but those that are likely to exist or to be obtainable for conventional submarines 10 to 15 years from now.

Second, significant advances are now being planned by submarine builders around the world. While there are different levels of commitment and progress, this process is well established and is being funded to produce results.

Third, the technological advances for this transformation of submarine design aren’t dependent on military requirements or defence industry economics. They are being propelled by a transformation in the management of energy more broadly—and that research provides a range of options and alternatives to sustain progress in submarine development.

Finally, despite these likely advances, the intention is still to deliver HMAS Attack to the RAN towards the end of this period of transformation with completely outmoded and outperformed lead–acid batteries.

We acknowledge the absolute importance of safety, but we believe from the direction of technical development that the safety risks of light-metal batteries in submarines can be managed.

Historically, the effectiveness of lead–acid submarine batteries has been constrained by their limited performance spectrum. They frequently operate at the extremes of their capacity, suffering performance degradation through the process and hence reduced safety margins.

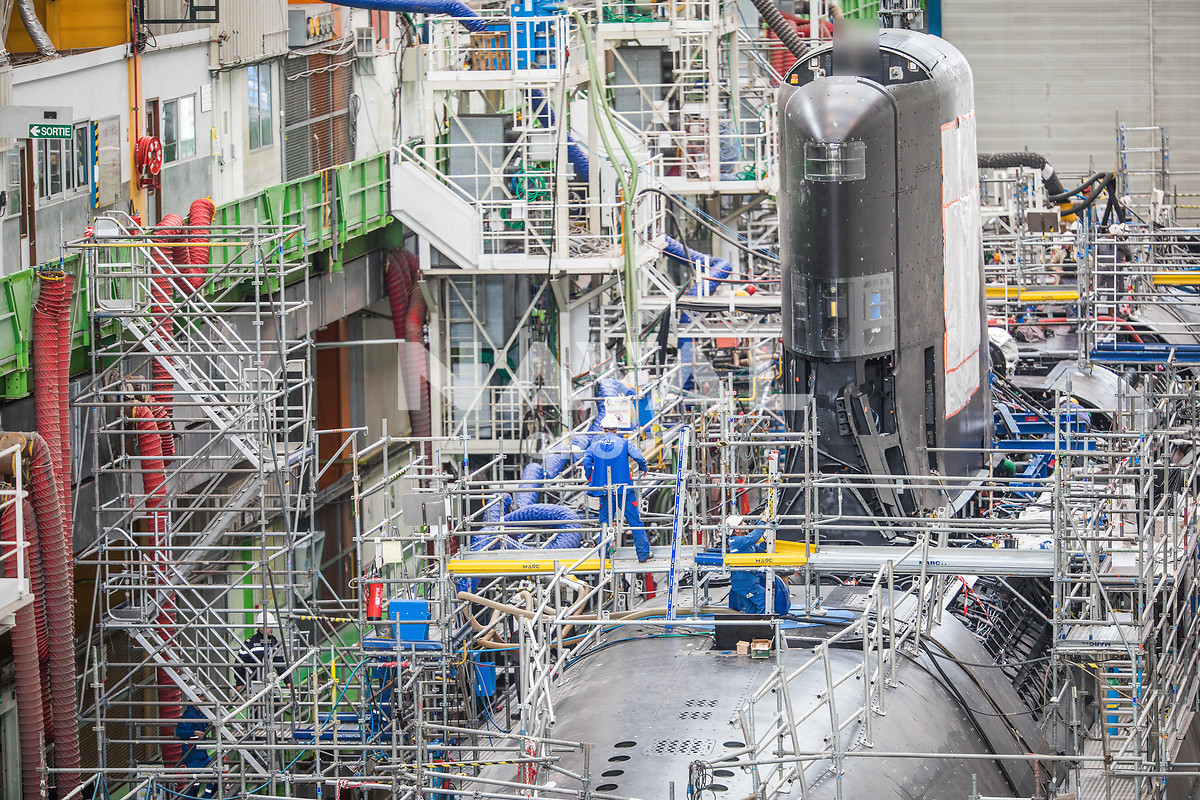

In contrast, the superior energy capacity and performance of light-metal batteries provide increased safety margins in all modes of operation. Naval Group regards lithium-ion battery technology as inherently safer than its lead–acid counterpart. This judgement is reinforced by South Korea’s decision, after 30 months of comprehensive study and evaluation, to use lithium-ion main batteries in the KSS-III batch 2 submarines. In East Asia, two designs of small, special-purpose submarines with light-metal power systems have recently been launched.

These vessels will be in the water for up to a decade before HMAS Attack, but data on their operation will be but a fraction of that gained from the increasing use of light-metal batteries in most areas of economic activity. Major automotive companies indicate that 50% of their models will be electric powered by 2030. Electricity grid stabilisation batteries are increasing rapidly in size and number.

Such developments, and the spread of domestic and small business storage, will provide both the operating experience and the market power to support investment in research and development that will accelerate the rate of evolution of battery technology significantly.

We have not attempted to second-guess the battery chemistry that might come to be preferred for submarine usage. The development of options will be driven by the demand of an expanding market. Automotive experience is relevant for the design of submarine power systems—the battery cells to be used for the KSS-III batch 2 submarines are those used in the latest version of the BMW i3 electric vehicle.

It seems, unfortunately, that HMAS Attack will be delivered with a lead–acid main battery. Designing the future submarine so that it incorporates nothing that hasn’t already been to sea in a submarine is one of the program’s primary risk-reduction strategies.

The already long development schedule for the first of class is driven by a determination to avoid what happened with HMAS Collins, whose construction began with detailed design still underway. These acquisitions strategies leave few options for innovation, even though completion of the design for the Attack is still some years away.

However, we agree with Greenfield that energy storage capacity and performance in Australian submarines must be improved. We believe that the best option for achieving this with the Attack class is to run a parallel design for a light-metal battery system to be fitted in the second of class—similar to the approach adopted by South Korea for the KSS-III batch 1 (lead–acid) and batch 2 (lithium-ion) submarines—with lead–acid and lithium-ion battery modules of the same weight fitted into the same overall volume.

Management and funding of this task need not be a responsibility of the submarine program, or even of the navy. There’s a joint-force requirement to understand the implications of emerging energy technologies if the Australian Defence Force is to remain operationally effective.

Deployed operations are enhanced by new systems requiring electrical energy. There will be an increasing need to recharge unmanned systems and for sufficient energy to sustain the ‘I’ in AI in a more complex and networked battle space.

Such developments seem ubiquitous and unstoppable, yet the ADF and Defence have no integrated mechanism to comprehend and respond to the energy demands of modern combat. A central agency—an ADF operational advanced energy centre—should be established to oversee the development of advanced energy capture and management, including identifying energy requirements and preparing options to solve problems such as the pathway for installing light-metal batteries in the Attack-class submarines.