Russia’s revenge

Empires never fall quietly, and defeated great powers always develop revanchist aspirations. That was the case for Germany after World War I: a humiliating peace agreement and the offer of former German territories to the country’s weaker neighbours helped to lay the groundwork for the awful revisionist adventures of World War II. And it’s the case for Russia today.

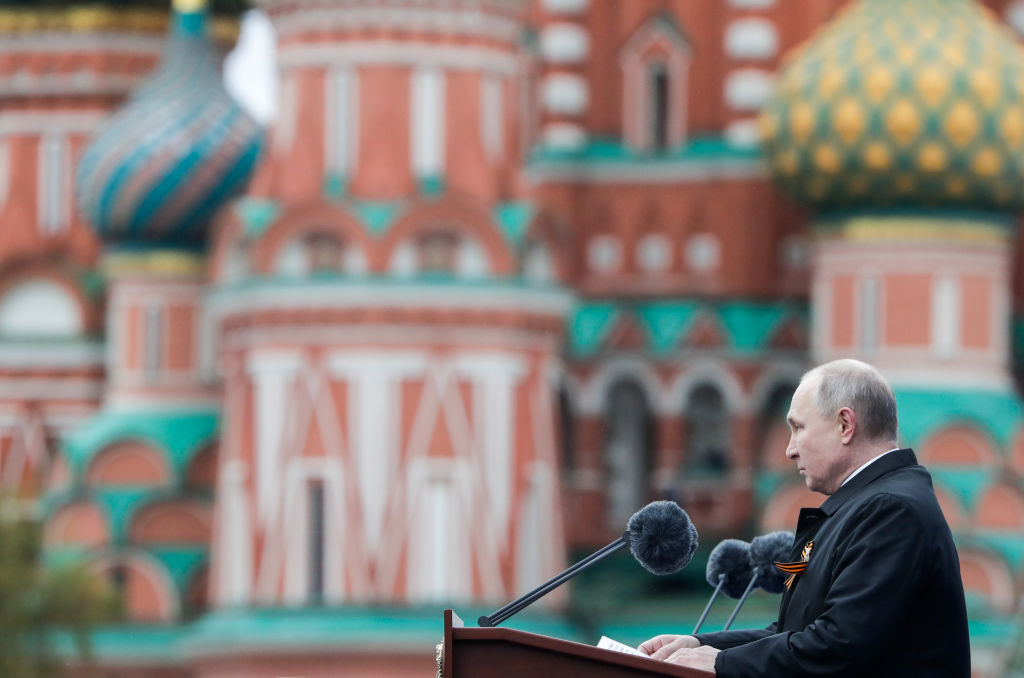

In 2005, Russian President Vladimir Putin called the Soviet Union’s collapse ‘the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the [20th] century’. So, under the pretext of protecting ethnic Russian minorities outside Russia’s borders, he’s attempting to reverse it.

Ultimately, Putin seeks a return to the post-war order, with a new Yalta-style agreement enshrining Russia’s recovery of the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. In his view, this approach is essential to ‘peaceful development’. Through its heroic victory over fascism—which the West seeks to diminish with its ‘historical revisionism’—Russia earned its place in the top echelon of the global power hierarchy.

Of course, in practice, Russia already maintains a sphere of influence. It does so, for example, by sustaining ‘frozen’ conflicts in former Soviet republics, from the clash between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh to the dispute over Transnistria, an unrecognised breakaway region of Moldova.

Russia also intervenes to help Kremlin-friendly governments quell domestic dissent, such as in Belarus and Kazakhstan. And it has brought most of the former Soviet republics into the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization, under which it keeps military bases in Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. Tajikistan is also home to Russian military bases, as are Abkhazia and South Ossetia, secessionist regions of Georgia that Russia recognised as independent sovereign states after its 2008 invasion, which effectively ended Georgia’s bid for NATO membership.

But a prized piece of Russia’s sphere of influence might be slipping away. The focus of the current standoff between Russia and the West over Ukraine reflects the country’s size and strategic value. But there’s also a historical and emotional component to Putin’s commitment to keeping the country in the Russian fold.

As Putin told a boisterous crowd after annexing Crimea in 2014, Ukraine represents the Orthodox Christian kingdom of Rus, the basis of Russian civilisation. Crimea has ‘always been an integral part of Russia in the hearts and minds of people,’ he said, and Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, is ‘the mother of Russian cities’. More recently, he has repeated his longstanding claim that ‘Ukraine is not even a country’; the ‘greater part’ of its territory ‘was given to us’.

Whether Putin’s version of history is accurate is immaterial. There is hardly a country that hasn’t reinvented the past to serve the needs of the present. What matters is his commitment to the goals he is pursuing—and the context in which he is pursuing them.

Putin is clearly willing to go to great lengths to keep Ukraine out of NATO. What he may not have accounted for, however, is that the stakes are also high for the United States, whose global reputation has been severely eroded recently, not least by the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan and the country’s subsequent takeover by the Taliban.

Allowing Russia to make a mockery of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum (to which Russia is a signatory) guaranteeing Ukraine’s territorial integrity would upend the European security system and deal a death blow to America’s global standing. Why would South Korea, Taiwan or Japan trust American security guarantees against China’s designs in East Asia? Why would Iran sign a new nuclear agreement with the US?

Although US President Joe Biden has ruled out direct military intervention, a full-scale invasion—or even a ‘minor’ one aimed, say, at creating a territorial corridor between Russia and Crimea by annexing land in eastern Ukraine—could well trigger a resolute American response. Even if it didn’t, and Russia managed to defeat Ukraine’s military—the third largest in Europe—pacifying the country wouldn’t be easy. An invasion of Ukraine could turn out to be as damaging for Russia today as the invasion of Afghanistan was for the Soviet Union in the 1980s.

Putin might have realised this by now, and thus may welcome a face-saving diplomatic solution to the crisis he has created. But the standoff will nonetheless have a lasting impact. After all, Putin has already reaffirmed that Russia is a revisionist power capable of disrupting the security arrangements Europe built in the aftermath of the Cold War.

In particular, the crisis has exposed the divisions in the transatlantic alliance. Plagued by a ‘double addiction’ to US security guarantees and Russian gas, and weighed down by the ghosts of its history, Germany has avoided a commitment to a NATO response. In fact, most European countries were unhappy with the sanctions imposed on Russia after the annexation of Crimea, and still disagree with the US about what should trigger new sanctions. And none of America’s European allies is eager for Ukraine to join NATO anytime soon.

The origin of Russia’s resentment towards NATO enlargement can be traced to February 1990, when US Secretary of State James Baker assured Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would expand ‘not one inch eastward’. In September of that year, as part of the Two Plus Four Agreement that permitted German reunification, the Soviets consented only to NATO membership for Germany. Robert Gates, who became CIA director the following year, admitted that the Russians were ‘misled’. As a result, while Leningrad was almost 2,000 kilometres from NATO’s eastern edge at the end of the Cold War, St Petersburg is now less than 100 miles away.

When the current showdown ends, the US should reconsider plans for NATO’s expansion. As George Kennan, the architect of America’s Cold War ‘containment’ strategy, predicted in 1997, NATO’s eastward expansion inflamed Russia’s ‘nationalistic, anti‐Western and militaristic tendencies’; restored ‘the atmosphere of the Cold War to East–West relations’; and drove ‘Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to [the West’s] liking’. This, he believed, could turn out to be ‘the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post–Cold War era’.

The US needs to take Russia more seriously. Dismissing the country as a ‘regional power’, as President Barack Obama did, is dangerously counterproductive. For all its weaknesses, Russia is a power to be reckoned with, and its legitimate concerns must be respected.