Projecting power with the F-35 (part 4): offshore bases

In previous pieces in this series I discussed the range limitations that are inherent in the design of tactical fighter aircraft. This includes the F-35A currently being acquired by Australia to constitute the core of its air combat force for a long time to come.

While aerial refuelling can increase a fighter’s time on station, there are limits on how much it can increase range. Even with tanker support the maximum achievable range for the F-35A is between 1,000 and 1,500 kilometres. Moreover, the number of F-35As that can be kept on station at those ranges is extremely small—sustaining just two fighters on station at 1,500 km would likely consume the Royal Australian Air Force’s current enabling capabilities.

One way to address these limitations would be to operate from airfields away from the Australian mainland. But it can’t be just any airfield. A minimum runway length of 8,000 feet, or almost 2.5 kilometres, is required to safely operate the F-35A. A shorter runway could be used, but then ordnance or fuel may need to be sacrificed to reduce the take-off weight and, as we have seen, fuel is crucial.

In addition, lots of pavement is required for the aircraft to stand on while they are maintained, refuelled and armed. A 2002 RAND Corporation study determined that a squadron of fighters required around 12,000 square metres of ramp space. Runway and pavement size requirements increase substantially if large aircraft like tankers and early-warning aircraft are also operating from the base, as does the required pavement strength. There’s also the need for substantial fuel reserves.

Gaining access to existing military airbases helps, as at least some of those things are already available. The risk with foreign airbases, of course, is that access is always at the owner’s discretion. Fortunately, Australia has a couple of airfields of its own that could help at Christmas Island and at the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. The latter has an 8,000-foot runway that supports the P-3 Orion maritime patrol aircraft, which has recently retired from RAAF service. According to Defence’s Integrated Investment Program, the runway is being upgraded to support the larger P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft. In June, Defence released a tender for works to strengthen and widen the runways, taxiways and aprons at an estimated cost of $200 million. No improvements to support fighter operations appear to be planned.

Figure 1: 1,500-kilometre range ring from the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

From the Cocos Islands, the F-35A could conduct strike operations in the vicinity of the strategic Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra at its extreme range of 1,500 km, assuming it had access either to air-to-air refuellers (potentially operating out of a mainland base) and/or a long-range strike missile. But maintaining a sustained presence would not be possible. Any operations over the Malacca Strait would be improbable, and they would be impossible over the South China Sea.

To project further north, Australia would need to rely on bases like Malaysia’s Butterworth that Australia has access to through an arrangement with the Malaysian government.

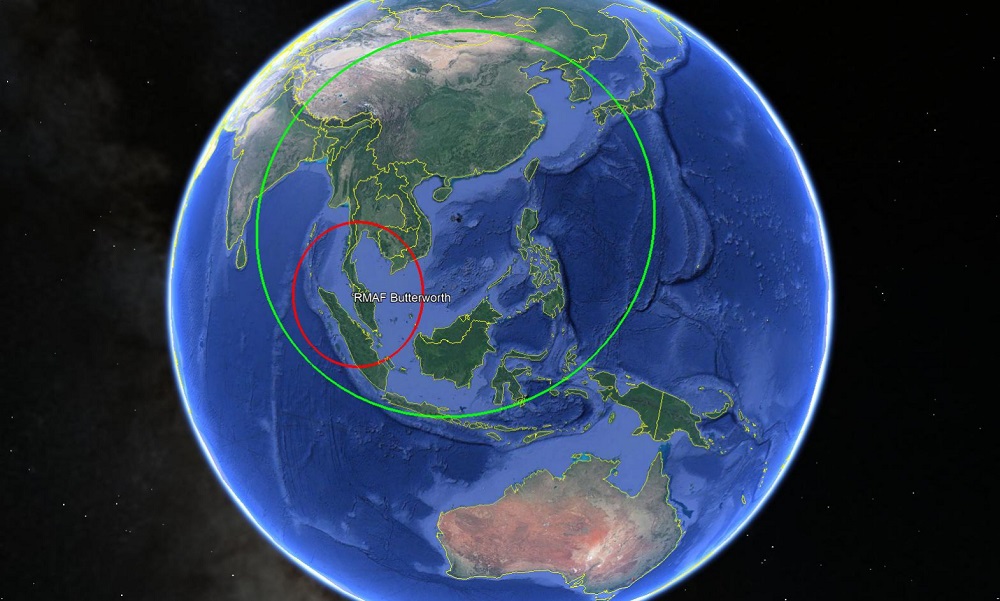

Figure 2: 1,000-kilometre range ring from Butterworth, Malaysia, and 3,000-kilometre range ring from Hainan, China

Butterworth puts the entire Strait of Malacca inside the F-35A’s unrefuelled range. It doesn’t get the F-35A very far into the South China Sea, although extending its range to 1,500 km through air-to-air refuelling would help.

Of course, in a contingency Malaysia might not feel that hosting Australian air combat operations was in its interests. The other big disadvantage is that Butterworth is within range of Chinese intermediate-range ballistic missiles. A 2017 report by the US Center for a New American Security argued that such weapons have the ability to ‘devastate’ US forces in Asia and the Pacific as they are sufficiently precise to target runways, aircraft hardstands and fuel depots. Currently Australia has no ability to defeat such a threat.

And there’s the rub. The further north we operate, the further inside China’s anti-access/area-denial zone we get. Of course, it’s hard to imagine a scenario where Australia would be operating so far from home without being part of a coalition with the US. But even the US is facing the same challenge presented by Chinese capabilities—its fighters are out-ranged by Chinese missiles and its defences could be overwhelmed.

Airfields will be even more critical to any contingencies in the South Pacific. Just as operations in World War II in the Pacific were focused on gaining or denying access to airfields, so they will be in any future conflict. But runways 8000 feet long are in short supply in the South Pacific. Those that do exist are international airports, not military airbases.

While the US military built many airfields across the region during the war, they were made for the aircraft of that time. Consequently, they are only 5,000–6,000 feet (1.5–1.8 km) in length and have very limited pavement. Many are in poor condition.

Manus Island in Papua New Guinea shows the potential advantages and disadvantages of offshore airbases in the South Pacific. Australia is currently working with PNG to upgrade the naval base at Lombrum on Manus. There’s also an airport on Manus at Momote, originally established as a WWII airbase. As the figure below suggests, air combat operations from Momote would close the gap between PNG and the US forces based at Guam.

In a worst-case scenario in which US power in the western Pacific had been severely weakened and China sought to physically isolate Australia from the US (essentially a key element of Japanese strategy in WWII), airpower based at Momote could interdict any Chinese attempts to project force into the southwest Pacific. If China does have intentions to establish military bases in countries like Vanuatu, Momote would in turn isolate them from China.

Figure 3: 1,000-kilometre range ring from Manus Island, Papua New Guinea

However, the runway at Momote is only about 6,000 feet long. Upgrading air combat operations will take a lot of concrete for runway extensions and aprons as well as fuel and munitions storage, particularly if larger aircraft will be operating from there. If just strengthening and widening the Cocos runway is set to cost $200 million, upgrading Momote to support air combat operations will cost many times more.

While China has demonstrated its ability to lay a lot of concrete on islands quickly, it’s not something that the Australian Defence Force can do overnight. If it’s something we think is important, we’ll need to build it well in advance of any contingency. As with all offshore bases, partners’ interests and sensitivities need to be heeded at both the local and national levels.

Depending on the threat, many other assets would need to be deployed to protect the airbase, such as ground-based air defence and other land forces. This would bring Defence’s amphibious capabilities into play. Fuel may need to be delivered by the navy’s tankers. Protection and supply elements could need more F-35As and the navy’s major surface ships to protect them en route.

While offshore airbases could help project Australian power further forward, they would likely require substantial infrastructure investment well in advance of their military use and, potentially, the deployment of a substantial joint force to sustain and protect them.