President Trump: four scenarios

At ASPI’s recent State of the Region Masterclass (PDF) I detailed some “alternate futures” for the Trump administration. In truth no-one, not even Trump himself, can be sure how his presidency will evolve. The future is unknowable, which is why using scenario tools that consider a range of alternate futures can be useful when considering Australia’s options for dealing with Trump.

Two key considerations will shape the long term character of the administration. The first is the extent to which Trump shapes a foreign policy of engagement with friends and allies or one which takes a relatively more isolationist bent. The signals are confused. Trump has certainly been critical of key allies, claiming they don’t carry enough of the security burden, but the President’s engagement with Shinzo Abe, Theresa May, Justin Trudeau and Malcolm Turnbull (hard going though that phone call was) all suggest a warming towards traditional allies. The Germans must be worried after Merkel’s awkward meeting—this is one key relationship that isn’t improving. Trump had an equally rocky start with China, but now Washington has reasserted its support for the One China policy which may allow for a more productive meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping. Trump’s comments about wanting to build a productive relationship with Putin are naïve considering the strategic differences between the two countries. For much of the rest of the world, the administration’s views are unknown. Trump harbours a suspicion—not without some foundation—that the outside world just sponges off the US.

The second key consideration shaping the character of the administration is whether it will stabilise into a more normal pattern of business or if Trump’s plan is to deliberately stay unstable. Again, there are contrary signs. Secretaries Mattis, Tillerson, Allen and National Security Adviser, Lieutenant General McMaster—the key national security players—look like reassuring professionals. But Trump was elected precisely because he ran a disruptive campaign; he’s continuing that approach with rallies and social media focused on his support base.

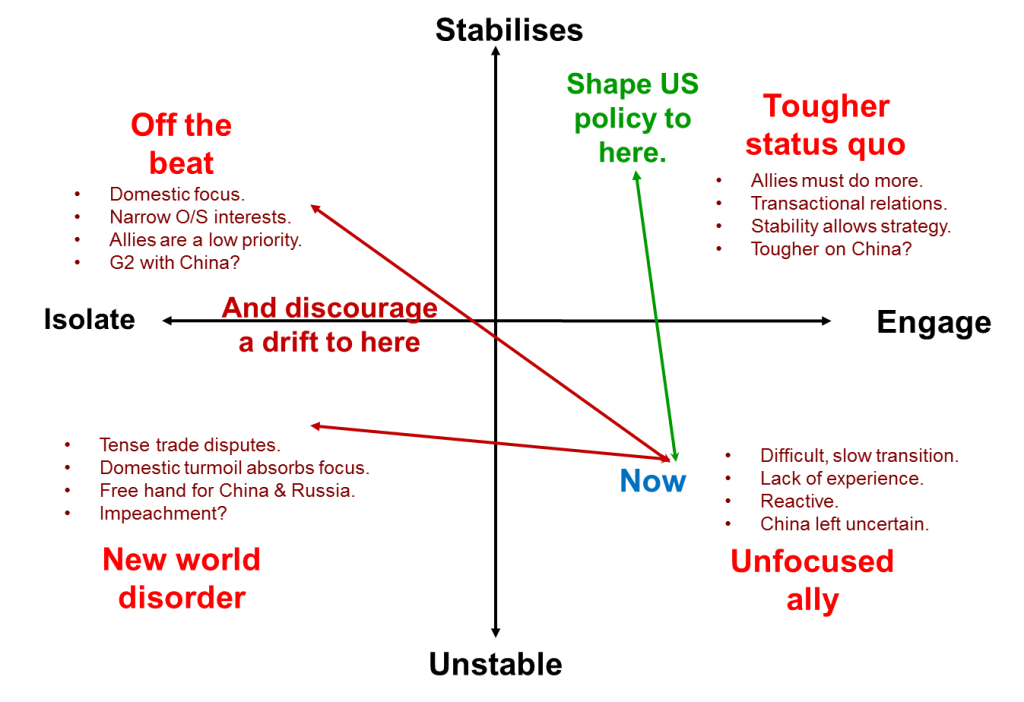

The intersection of those key driving forces—engagement or isolationism; organisational stability or disorder—point to four possible futures for the Trump administration. Right now the Presidency is unstable but it’s still engaging key partners. Think of this scenario as the world of the Unfocused Ally. The administration’s lack of focus means that it faces a difficult and slow transition to office: it took 50 days before Trump’s Cabinet met and literally thousands of political appointments are yet to be made. Key administration figures are starting from a very low knowledge base about international affairs. An Unfocused Ally will be reactive, unpredictable and keep friends and rivals constantly guessing about Washington’s next move. The One China policy? The two-state solution? Don’t expect finesse.

It’s possible that Trump will grow into the job. If the administration becomes more stable and engages allies, its approach will evolve into a Tougher Status Quo. We’ll see greater expectations of allies. Secretary Mattis recently delivered this message to NATO: ‘It is a fair demand that all who benefit from the best alliance in the world carry their proportionate share of the necessary costs to defend our freedoms.’ In this world Washington will be more transactional, more inclined to judge allies by their last military contribution to Coalition efforts and less motivated by the idea of historic alliances. Greater stability means that over time the administration may be less reactive and better able to develop strategic approaches to key relationships. Trump may develop a tougher policy towards Chinese adventurism than Obama—not that that’s saying much. In fact Beijing would probably prefer a consistent but tougher Washington than remaining in a cloud of confusion about the President’s next Tweet.

Moving over to the left hand side of the scenario diagram, an administration that becomes more isolationist and more stable in delivery becomes the cop Off the Beat. With a dominant domestic focus, this is an America in which traditional allies would lose relevance. China, Russia and Iran would look to consolidate attempts to dominate their neighbours. Japan, Germany and Australia, among others, must rethink their own security postures, assuming that the US would be less supportive. Trump might see this environment as a great place to practice the Art of the Deal internationally. Can he cut a deal with China? ‘You get Southeast Asia and we get trade protectionism.’ That would be a worrying place, but would enable the President to play to the voters that elected him.

The final scenario is New World Disorder, in which the administration swings to isolationism and sustains—or deepens—its instability. Just as Lenin understood, disorder can be a deliberate but risky tactic. Trump’s campaign was essentially an insurgency against the American political establishment. A number of his key staff, like senior adviser Steve Bannon, will continue that approach. There’s no point worrying about appointing hundreds of administration officials if the broader aim is to govern with a tiny cadre of ideologues in the White House. In the New World Disorder allies would struggle to gain attention. The administration might act on its rhetoric to ramp up trade disputes and Russia, China and others would have a freer hand for their strategic objectives. The administration would use instability as a tactic to sustain its anti-Washington voter base, but surely Congress would fight back. Impeachment may lie ahead as Trump struggles to accept that running a country is different to running a tight family business.

We shouldn’t pretend that Australia can shape much of that, but our interest is to do what we can to push the administration towards the stable and engaged scenario of the Tougher Status Quo and away from the isolationist scenarios. We can do that by making sure Malcolm Turnbull builds an effective relationship with Trump. We’ll have to do more in terms of alliance cooperation (our own strategic interests demand this), but rather than wait for America to set the price Canberra should design its own agenda for doing more together.

Is that what Australia will do? The signs are mixed. Unlike many world leaders Turnbull hasn’t yet gone over to Mar-a-Lago for a round of golf. He may calculate that there’s nothing in it for him domestically to get too buddy-buddy with Trump. A well-organised chorus of useful idiots in Australia are counselling Turnbull to distance himself from the US and embrace the world’s Chinese future. Too much of that and Trump might decide that isolationism is the right way to handle flaky allies. That, folks, would be neither great nor beautiful.