Leaders’ summit shows the Quad has grown up

Four years ago, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue was something only officials, not ministers, could engage in and there were studious denials that the grouping had anything to do with China’s use of power and economic coercion. Official statements were bland and actions were few.

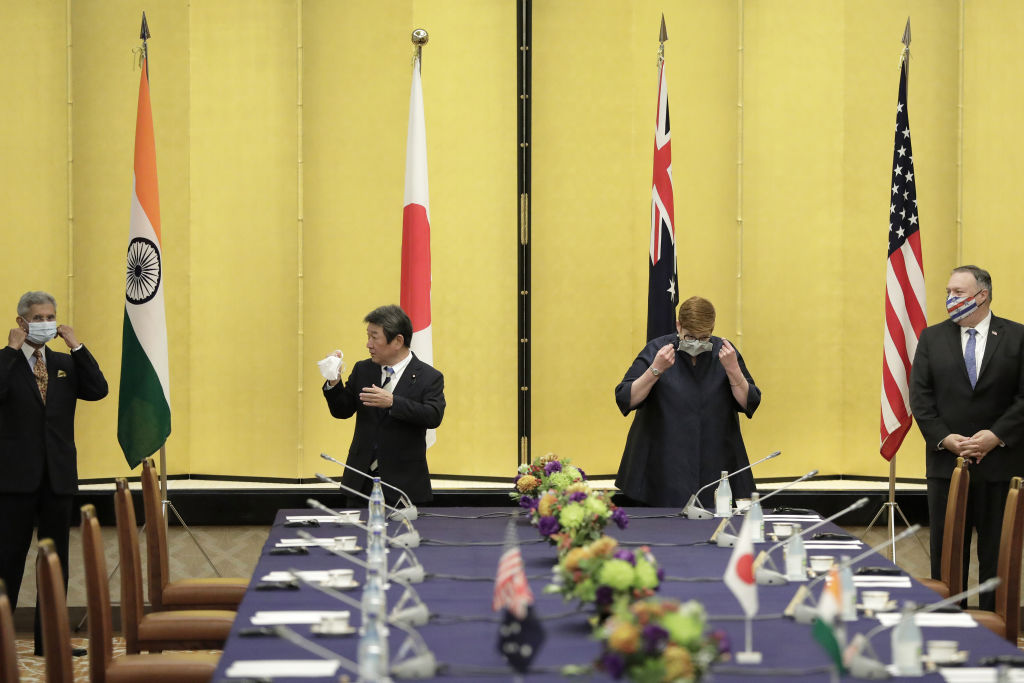

Since then, things that simply couldn’t happen according to received wisdom have kept happening. The Quad moved from a forum just for officials to a foreign ministers’ forum in late 2019. Last year, India’s Malabar naval exercise broadened to include Australia, making it a key naval exercise for the four Quad partners. And more foreign ministers’ meetings have been held since that start in 2019. This is now an agreed ‘forum architecture’, so beloved of students of international security forums and institutions.

The biggest development has happened at speed under the new US administration. President Joe Biden used his first call with Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping to give priority to ‘preserving a free and open Indo-Pacific’—a concise statement of what the Quad is all about. And now, just two months later, he and the prime ministers of India, Japan and Australia are getting ready for a Quad leaders’ meeting on Friday morning, Washington time.

This is happening because the Quad is a grouping that makes more and more sense as the strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific develops.

The momentum for India, Japan, the US and Australia to cooperate on security, economics, technology and public health comes partly from global interconnections, and partly from the converging assessments each nation is making about the behaviour and actions of China under Xi.

The leaders are driven by Chinese actions—that familiar list of military aggression in the South and East China Seas, around Taiwan and on the India–China border; acute human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet; and economic coercion, cyber hacking and political interference in other nations, combined with the expulsion or arbitrary detention of foreign nationals. Add in Beijing’s continued failure to be transparent about either the origins of the pandemic or the efficacy and safety of Chinese Covid-19 vaccines.

But Narendra Modi, Yoshihide Suga, Scott Morrison and Biden are also responding to very strong public sentiment in each of their countries.

This is a symptom of China’s soft power collapsing across much of the world.

That’s shown in a deluge of surveys, including the October Pew Research survey showing unfavourable views of China at historic highs across the developed world, Singapore’s ISEAS think tank’s February ‘State of the region 2021’ survey showing even higher concern about China ‘not doing the right thing’ after the experience of 2020, and the most recent Pew assessment of views in the US on China, released last week.

These surveys tell us that populations across the Indo-Pacific, in Europe, North America and Australia, are ahead of their governments—and certainly many in their business communities—in appreciating the implications for their security, wellbeing and prosperity of the way China is behaving and acting under Xi.

Beijing almost certainly discounts these populations’ views. As we see with the National People’s Congress, the Chinese government is advancing its strategy for growing and using power and influence through a combination of hard power, the attraction of making money from China’s large market and a plan to dominate the sources of future technological and economic power. That’s enabled by a supportive network of advocates in the political, business and academic elites of other nations, which Australian journalist Rowan Callick has described well in his recent paper for the Centre for Independent Studies, The elite embrace.

Domestically, the CCP is adept at controlling and directing public sentiment, using its own elites, security agencies and, increasingly, high-technology surveillance and social media management. So maybe it’s simply assuming that keeping foreign elites onboard will be enough to enable the continued pursuit of its ‘China dream’ of a Sino-centred world, with China under continued party-centred control.

That assumption misunderstands how much of the rest of the world works. Governments in India, the US, Japan and Australia must respond to their populations, in ways that China’s autocrats can’t get to grips with.

We are a world away from 2007, when furious diplomatic démarches from Beijing resulted in officials quickly disowning the idea that the Quad would do anything meaningful.

Quad leaders now know that actions they take that reduce the influence of aggressive Chinese power will be welcomed and rewarded domestically. And a practical agenda for the Quad that has this effect also, conveniently, can address some core policy directions of each of the leaders. It’s not often that a multilateral grouping can so effectively combine national and joint interests.

Look at the agenda for Biden, Morrison, Suga and Modi: accelerating vaccine production and rollout, finding practical approaches to increase economic cooperation in ways that reduce supply-chain vulnerabilities, and identifying common actions on climate change that have the by-product of advancing the economies and high-tech industries in each of our countries.

Each of these topics is a net good for each of our leaders, and each is given energy and urgency by China’s actions over recent years, and in the new five-year plan that’s now being signed off by the National People’s Congress.

The combined weight of the Quad partners can be a defining good, achieving multilaterally what each nation couldn’t alone—an idea at the heart of Biden’s interim national security guidance.

Vaccine production and rollout is an example. The US has developed what open scientific data tells us are some of the safest, most effective Covid-19 vaccines—the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is a single-dose shot, for example, reducing the scale and challenge of mass vaccinations. India, as a medicines-production superpower, has the horsepower to make these at speed and scale. And the combined financial and logistical capacity of the Quad partners, along with their strong relationships across South and Southeast Asia all add up to a package that will make a difference to the safety and wellbeing of a major chunk of the globe. Progress here works directly with Morrison’s South Pacific step-up, and with each of the partners’ Indo-Pacific strategies.

The Quad forum is not the sum of all things, although it is complementary to other groupings that also have a role in enhancing positive cooperation that reduces nations’ vulnerabilities, whether to pandemics or coercion. The G-7 and the Five Eyes come to mind, as do NATO, a renewed EU–US partnership and a revitalised US alliance network.

However, the Quad is developing as a working forum for leaders to generate momentum on practical actions. Having to cooperate without all the traditional sherpas, summitry and bureaucracy of other forums is one of the defining positive effects that Covid has brought us.

The Quad is now much broader than the ‘security dialogue’ that restarted in 2017, and its utility will increase given the world we are living in. This may be what Beijing is most anxious about—a multilateral grouping that is action oriented and agile enough to provide new challenges to how China wants the world to work.

For all the reasons that Beijing desperately wants the Quad to fail, it is in our interests to have it grow, prosper and demonstrate its own positive agenda.