Jimmy Carter: a man of humanity

Former Democratic US President Jimmy Carter, who is spending the last stage of his life in home hospice care at the age of 98, will be most remembered not only for his humanity and humility but also for his handling of two highly troublesome foreign policy issues that dominated his tenure in office (1977–1981). The Iranian revolution and its outcome confronted him with a humiliating crisis, and his efforts in bringing about a peaceful resolution of the Arab–Israeli conflict failed to secure a just peace for the Palestinians.

Soon after assuming office, Carter was seriously challenged by transformative changes in Iran—one of the pillars of Pax Americana in the Middle East. The pro-Western monarchy of Mohammad Reza Shah was besieged with a revolutionary uprising, resulting in its overthrow and replacement by an Islamic government, led by the Shah’s key religious opponent, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The new leadership declared Iran an Islamic republic with an anti-US stance for its support of the Shah’s autocracy and vehement opposition to Israel for its occupation of the Palestinian lands, especially Jerusalem as Islam’s third holiest site.

Initially, Carter sought a modus vivendi with the Islamic regime, but the situation was compounded by a group of Khomeini’s militant supporters overrunning the US embassy in Tehran and taking 53 of its personnel hostage in November 1979. As Khomeini used the development for consolidating power and punishing the US, the ‘hostage crisis’ lasted 444 days or the entire remaining term of Carter’s presidency. The episode, which resulted in a total breakdown of relations between the two sides, proved very humiliating for Carter.

As a man of strong Christian faith with a committed stance for peace, Carter pursued all non-confrontational means to secure the release of the hostages, but when those efforts failed, he ordered a military rescue attempt, called Operation Eagle Claw, in April 1980. The mission ended with US helicopters crashing in the Iranian desert, which enabled Khomeini to claim it as punishment from God and could not have been more harmful to Carter. A further option was to go to war with Iran, but that was infeasible given Carter’s dedication to peace and the risk involved for the hostages.

Although both Carter and Khomeini were devotees of two Abrahamic faiths, Khomeini was not for turning as an Islamic revolutionary. After having demonstrated his power against the United States and making Carter appear as a ‘weak president’ in the eyes of the American public, Khomeini finally released the hostages on the eve of the swearing-in of Carter’s Republican successor, Ronald Reagan, on 21 January 1981.

Carter went on to further redeem himself as a very faithful and humane Christian in the service of the needy in the US and abroad. As for Khomeini, his legacy of an Islamic regime ever since his death in 1989 has progressively endured US enmity and sanctions and faced US public discontent. The regime is currently beset by widespread public unrest, with troubling times ahead.

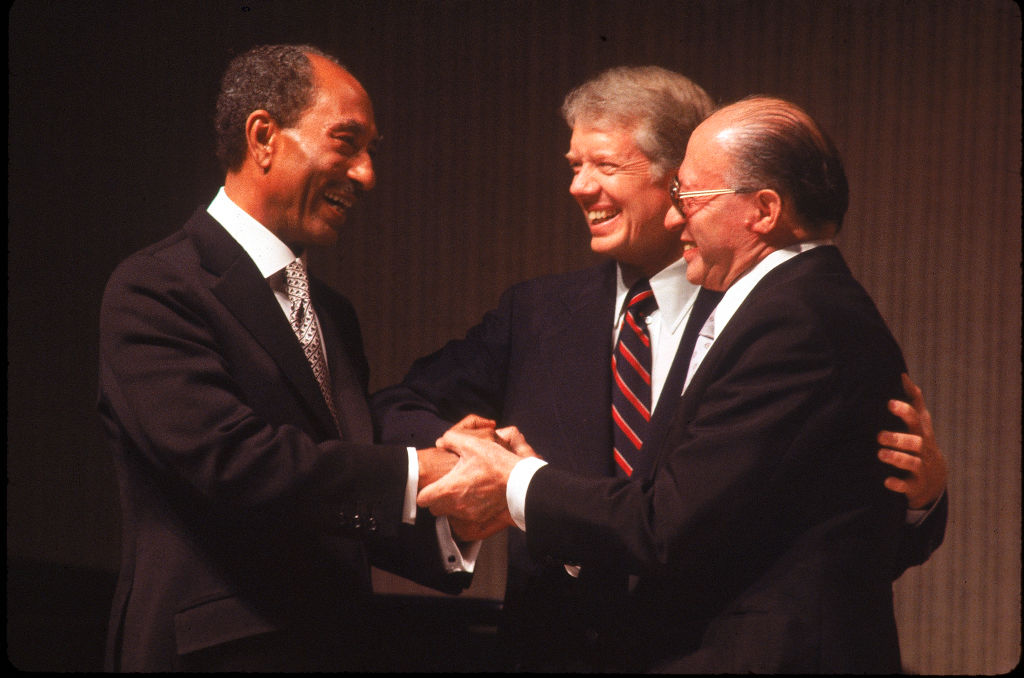

The other foreign policy issue where Carter sought to do good, but could not achieve entirely what he wanted, concerned his role to secure the right of the Palestinians to self-determination and an independent state of their own. He managed to bring together Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat at Camp David in 1979 to negotiate peace to end the Middle East conflict. The outcome, in which he played a critical and impartial mediation, was the signing of two Camp David accords. One was to establish peace and normalise relations between the two sides. The other was to create an independent Palestinian state within five years out of the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, which Israel had occupied since the 1967 Arab–Israeli War.

Israel implemented the first accord, which involved its withdrawal from Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula in 1982 in return for Egypt’s formal recognition of Israel and establishment of relations between the two sides. The peace treaty that the former foes signed still holds. Jordan concluded a similar treaty with Israel in 1994, and more Arab states have since followed suit.

However, Israel reneged on the second accord, to Carter’s total disappointment. In his book The blood of Abraham, published in 1985, he castigated Israel for it. Abhorred by Israel’s repressive treatment of the Palestinians in the continued occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem and blockaded Gaza, Carter came to view Israel as an ‘apartheid state’. He stood by the support of the international community, including Israel’s main ally, the United States, for a two-state solution as the best option for a lasting and just peace.

When Carter departs, he will be remembered in history as a man of great humanity and peace, despite his presidency having been seriously undercut by Middle Eastern vagaries. He will be missed in a world that badly needs more of his kind.