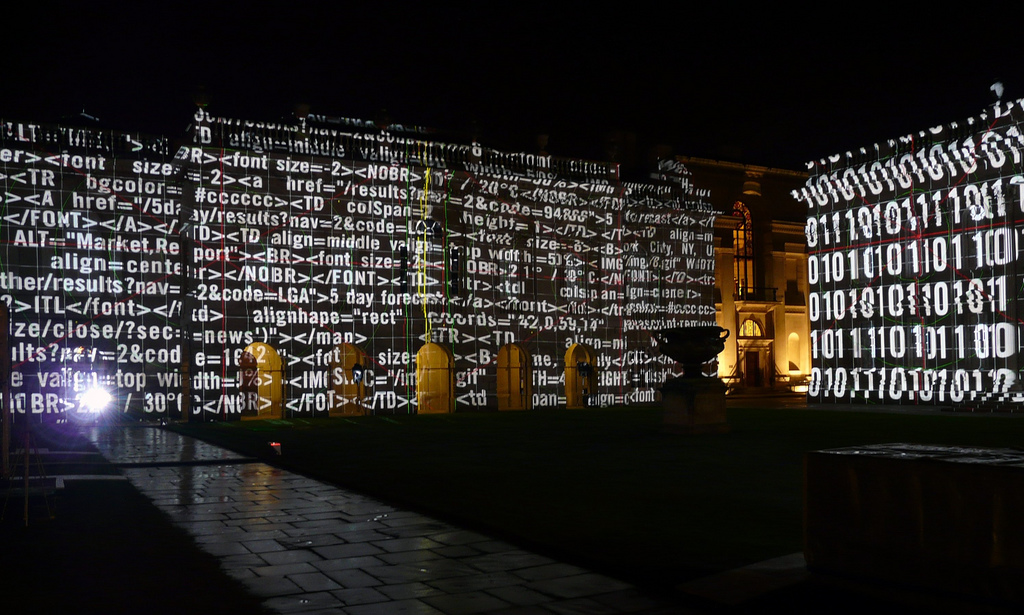

International cyber security: a divided road

In the globalised, interdependent world in which we live our modern lives, the keystone that keeps much of our economies, infrastructures, lines of communication, defence, security, intelligence and social capital enabled is the cyber domain. Due to its international nature, this domain has created intimate interdependencies between states and also new avenues for states to achieve their policy objectives. Furthermore, as the domain empowers individuals, non-state actors and the private sector, a large-scale cooperative approach between a large number of stakeholders is required. And as technology develops in quantum leaps, questions remain about how we, as interdependent actors, will manage the cyber front.

The Budapest Conference on Cyberspace 2012 was the second international conference in a process begun by the UK Government in 2011 in London to begin a dialogue on international shared principles in cyberspace and to outline an agenda for a secure, resilient and trusted global digital environment. What became abundantly clear through the course of the Budapest conference was the divergent intellectual paths that countries are now taking in regard to this issue, and how distinct ‘camps’ are being established in the debate.

Broadly speaking there are two approaches that have been established for the challenge of creating increased cooperation in cyberspace. The first is to develop formal international laws and/or treaties through state-dominated organisations, most notably the United Nations. This line of action is one endorsed most prominently by Russia and China. The second approach is to develop a range of commonly accepted principles (norms) of behaviour which frame discussion and debate, which are more inclusive, provide more options and more gradually change mind-sets and behaviours. Those in this camp are countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Korea and most European nations.

There was palpable tension in the air in Budapest between these different positions, and this was echoed in William Hague’s opening remarks: ‘This is the growing divergence of opinion and action between those countries seeking an open future for the internet and those who are inching down the path of state control.’ Led by the European nations there was much time spent discussing the human rights aspects of cyber security, based on the premise that internet freedom is a fundamental right, especially by a highly animated President Toomas Ilves of Estonia, who proclaimed that: ‘They [China and Russia] will want to impose their authoritarianism on us, let’s not let them do this.’ This prompted the Chinese speaker who followed, Huang Huikang, Legal Advisor to the Chinese Foreign Minister, to ‘wonder if I am in the wrong place to attend a conference on cyberspace, it seems that I could be in Geneva at a human rights meeting.’ This underlined the feeling that many Chinese representatives had that they were being unnecessarily lectured to and underlining the divisions that exist between these two camps, a tension that was not settled by the end of the conference.

Resolving the divisions between the two camps is going to be a bumpy road ahead and there will have to be a great deal of work done on confidence building measures to lower the atmosphere of mistrust. One initiative announced by the UK government was of their plans to invest £2 million (AUD$3.14 million) to create a Centre for Cyber-Security Capacity Building which will look to increase collaboration, capacity building, good governance and skills sharing so that in an attempt to close the gap between those countries who understand the nature of the problems and how to respond and those who simply cannot keep pace. It is certain that more innovative initiatives like this need to be examined by a range of stakeholders, including the public and the private sectors to ensure that advice provided is balanced and processes are not state dominated.

The ‘elephant in the room’ was clearly the fact that there is so much malign cyber activity currently on-going, both state and non-state led, which outpaced much of the discussion going on. Therefore, whilst states discuss the principles upon which a framework for the ‘rules of the road’ in cyber space might be arranged, both the technology and techniques used for negative purposes are accelerating far beyond the boundaries of international discussion, and this challenge means that nations need to begin thinking outside of the conventional pathways for solving this issue. Much of the frameworks upon which the discussion are taking place, appear to an observer, as very similar to those which took place around Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) in the 20th century, yet the technological advances taking place in those areas were at a far slower rate of development than those in the cyber domain, and the frameworks provided for stemming the proliferation of WMD are just not up to the task of bounding the use of cyber space, especially when the technology being discussed does not fall under the primary control of the Government.

The internet has been harnessed by the public and private sector in a way which has far outstripped Government’s ability to keep up, therefore, to now impose governmental boundaries on its use is highly problematic, and could stem economic innovation. What is certain is that this is only the beginning of a protracted international dialogue, and once we arrive at the next conference in Seoul in October 2013, we shall see how much further the divided road has become.

Tobias Feakin is a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Image courtesy of Flickr user tz1_1zt.