In defence of surface ships

Recent analysis (PDF) and commentary by ASPI (echoed elsewhere) has questioned the wisdom of the Government’s intent for a new fleet of surface ships. These concerns boil down to the presumed vulnerability of such vessels to future anti-access/area denial systems, including shore-based missiles and the increasing numbers of submarines that will soon prowl the waters to our north. If, after all, surface ships are just ‘floating targets’ is it prudent to invest in them?

Such criticisms miss two important themes related to naval ships, or more specifically Major Surface Combatants (MSC, i.e. blue-water vessels such as frigates and larger ships).

First, the received wisdom of the ‘increasing vulnerability’ of MSC isn’t clear-cut. Indeed, there are solid grounds for assessing it’s the submarine’s lot that will worsen due to the decreasing efficacy of its key virtues of stealth and torpedos.

As noted most recently by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, the future ocean environment will likely to be one where all naval assets are more easily detectable. This will be due to the prevalence of distributed advanced sensors linked to sophisticated data processing capabilities.

Such developments will be much more adverse for submarines. Ships have always been detectable, relying hence on electronic warfare, defensive weapons and armour for protection. This trend is continuing, with advanced defensive systems such as lasers and rail-guns now rapidly maturing and potentially able to outmatch increasing threats. But submarines will always depend on stealth due to their comparatively slow speed, limited manoeuvrability and near absence of defensive weapons and armour. Thus more transparent oceans will likely not make surface ships much more vulnerable, but submarines may become much more detectable, and destructible, than at any previous time.

Further, in the competition between ship and submarine, the essential weapons advantage of the latter has been its torpedoes and the lack of effective defence against them (MSC have a variety of electronic, missile and gun defences to protect against submarine-launched missiles).

Torpedoes, however, are becoming a much less certain proposition as ‘hard kill’ defensive systems (essentially anti-torpedo torpedoes) approach technological maturity. Will a submarine still triumph when neither its missiles nor torpedoes have surety of killing a target? Especially when launching its weapons, in an ocean of distributed sensors, will provide the flaming datum that accurately discloses its location?

These issues aside, the second and more important theme regarding MSC is their demonstrable delivery of more capability at lower cost than other assets. As such, even if MSC do prove more vulnerable than submarines in the future, they are a worthwhile investment regardless, to achieve the best value for money.

While the main criticism of surface ships is their supposed vulnerability in high-end conflict between sophisticated adversaries, their contribution to national security isn’t properly assessed through such narrow contingencies. Instead, it’s in their support to the full range of tasks in which navies engage.

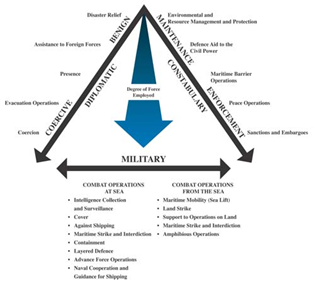

The position of a range of naval thinkers, and also that of the Australian Maritime Doctrine (AMD), is that navies fulfil three broad roles: military, diplomatic and constabulary (see diagram below, from AMD p. 100). In these roles, the constabulary (such as border protection), diplomatic (such as port visits) and lower-end military tasks (such as intelligence gathering) are far more common than all-out war between major powers.

Regarding these roles, the AMD observes that submarines have their greatest value in the (very rare) high-end combat operations and more common intelligence collection and special forces delivery tasks. This is due to their inherent stealth and the lethality of their armament of torpedoes and missiles.

These same characteristics also make them ill-suited to more common tasks. Their powerful weapons are inappropriate to counter smaller vessels or lower level threats, such as anti-piracy or border protection operations, and the reliance on stealth limits their applicability to diplomatic or constabulary activities.

Conversely, MSC clearly are able to address the full range of maritime roles. As diversely-armed (from machine guns to missiles) assets not relying on stealth, they can visit ports, fight piracy and support border protection. With powerful offensive and defensive capabilities, they can still effectively conduct high-end military roles to collect intelligence, deliver special forces and fight adversary ships and submarines.

When viewed then from the broader capability perspective, MSC fulfil more roles, more ably, across more probable scenarios, than submarines. And in doing so at around $39 billion for a number of Frigates and Offshore Patrol Vessels , instead of up to $50 billion for up to 12 submarines—clearly MSC deliver better value for money.

Indeed, the question that might be asked isn’t so much should Australia acquire MSC, but rather should we invest so much in submarines when ships deliver more bang for buck. A fleet with more MSC would provide a larger, more flexible, and capable Navy and thus a more secure Australia. It may also provide a sufficient body of shipbuilding, upgrade and maintenance work to sustain a broader Australian naval industry. All these issue deserve due consideration before we overly critique the decision to acquire more surface ships.