How China views the Ukraine crisis

Beijing may be 6,500 kilometeres from Kyiv, but the geopolitical stakes for China in the escalating crisis over Ukraine’s fate couldn’t be higher. If Russia invades Ukraine and precipitates a drawn-out conflict with the United States and its Western allies (though a direct military confrontation is unlikely), China obviously stands to benefit. America will need to divert strategic resources to confront Russia, and its European allies will be even more reluctant to heed US entreaties to join its anti-China coalition.

But if US President Joe Biden defuses the crisis by acceding to some of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s demands, China will likely end up worse off strategically. While Putin will reap the benefits of his coercive diplomacy, and Biden will avoid a potential quagmire in Eastern Europe, China will find itself the sole focus of America’s national security strategy. Worse still, after Putin has skilfully exploited the US obsession with China to re-establish Russia’s sphere of influence, the strategic value of his China card may depreciate significantly.

For Putin, capitalising on Biden’s fear of being dragged into a conflict with a secondary adversary (Russia) in order to extract critical security concessions is a risky but smart move. But ordering an invasion of Ukraine—and thus effectively volunteering to be America’s primary geopolitical adversary, at least in the short to medium term—is hardly in the Kremlin’s interest. Crippling Western sanctions and the high costs of fighting an insurgency in Ukraine would almost certainly weaken Russia significantly and make Putin himself both domestically unpopular and more dependent on Chinese President Xi Jinping.

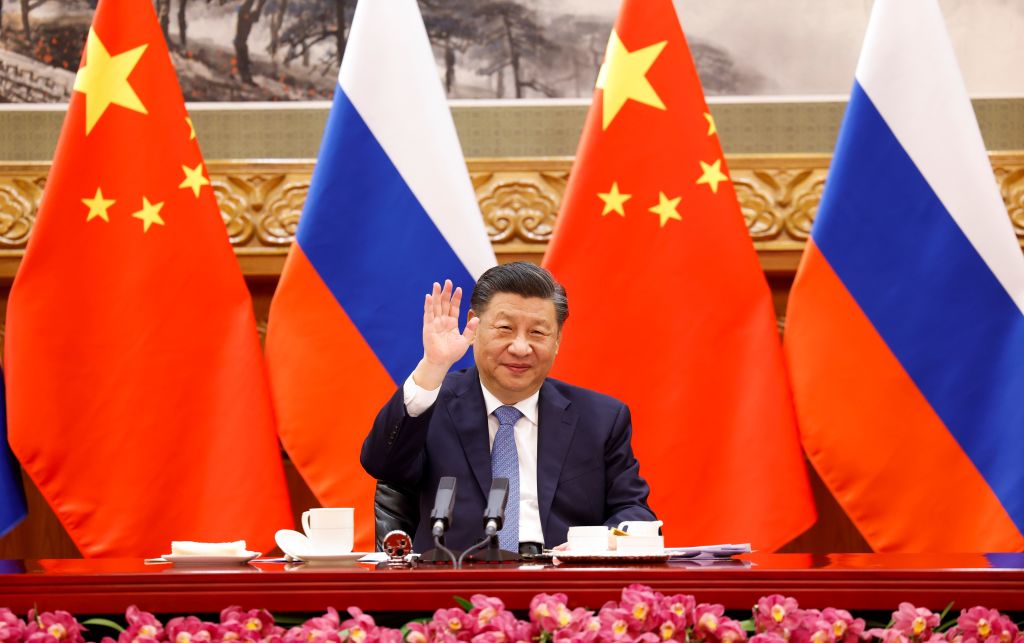

Intriguingly, despite the high stakes for China in the Ukraine crisis, the Chinese government has been extremely careful about showing its hand. While the heightened tensions dominate Western media headlines, Ukraine receives scant coverage in the official Chinese press. Between 15 December (when Putin and Xi held a virtual summit) and 24 January this year, the People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, carried only one article about the crisis—on the inconclusive talks in mid-January between Russia and the US and its NATO allies. Editorials or commentaries voicing Chinese support for Russia also are notable by their absence.

Even more intriguingly, the summary of the Putin–Xi summit released by the Kremlin claimed that Xi supported Putin’s demand for Western security guarantees precluding NATO’s further eastward expansion, but the Chinese version, published by the official Xinhua news agency, contained no such reference. Instead of explicitly endorsing Putin’s position, Xi’s statement was vague and general pabulum about ‘providing firm mutual support on issues involving each other’s core interests’.

The pattern continued when Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi spoke to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on 27 January. Western media characterised Wang’s statement on Ukraine as an expression of support for Putin. In fact, Wang planted China’s diplomatic stake squarely on the sidelines, saying only that ‘Russia’s reasonable security concerns should be stressed and resolved.’

Chinese reticence on Ukraine suggests that Xi is carefully hedging his bets. To be sure, Putin’s aggressive diplomacy is serving Chinese interests, at least for now. Should he decide to invade Ukraine and divert US strategic focus away from China, so much the better.

But, assuming that Xi doesn’t know the Kremlin’s real intentions vis-à-vis Ukraine (it’s doubtful that Putin has shared them with his Chinese counterpart), he is prudent not to show his own cards either. Any expression of unequivocal Chinese support for Putin’s demands could leave China with little wiggle room. At worst, goading Putin down the path of war could be construed in some circles in Moscow as a diabolical Chinese plot to use Russia as a strategic pawn in the Sino-American cold war. Alternatively, should Putin choose to pocket face-saving gains in order to avoid a potential disaster, China would look foolish for having backed the Kremlin’s unattainable demands.

Strategic uncertainty aside, China’s rulers know that explicitly supporting Putin will almost certainly antagonise the European Union, which is now China’s second-largest trading partner. In Chinese policymakers’ strategic calculation, it is vital to prevent the US from recruiting the EU into its anti-China coalition.

Ukraine’s independence and security are crucial to the EU, and Chinese efforts to aid and abet Putin would trigger a European backlash. At a minimum, the EU could make China pay by restricting technology transfers and expressing more diplomatic support for Taiwan. In particular, the EU’s Eastern European members, which have fewer trade ties with China but are most threatened by Russia’s aggressive stance, are in a much stronger position than large member states to play the Taiwan card as retaliation against China. Few in the Chinese leadership are likely to consider that a risk worth taking.

China’s leaders are realists and know that they can do little to influence the outcome of the crisis in Ukraine even if they choose to intervene publicly. With Putin holding most of the cards in the ongoing standoff, China’s diplomatic support is unlikely to alter the strategic calculus of the principal protagonists in Washington, Brussels or even Moscow. Its influence will increase dramatically only if Putin rolls the dice and invades Ukraine, because he will then need Chinese economic support to lessen the impact of Western sanctions.

But for now, all this is speculative as far as Xi is concerned. Although a superpower, China is temporarily reduced to being an onlooker, watching both anxiously and hopefully on the sidelines as the Ukraine crisis unfolds.