History shows the West’s sanctions on Russia could backfire

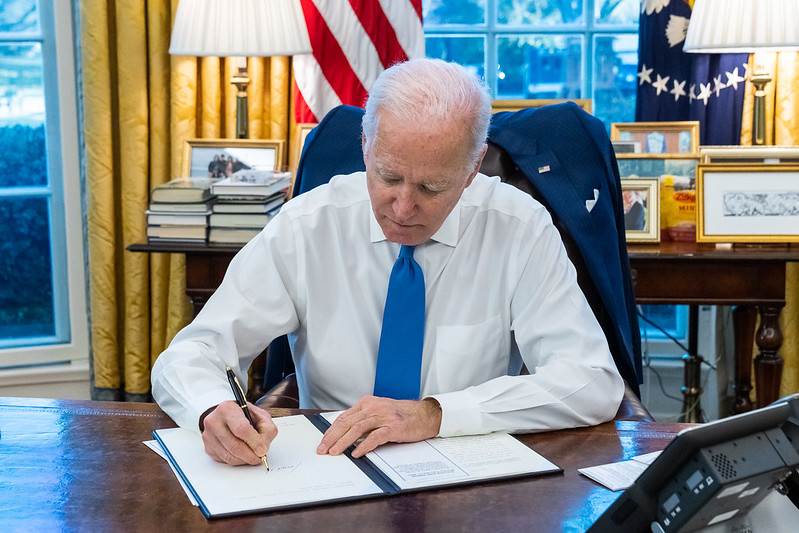

President Joe Biden announced last week that the US will tap into its emergency oil reserves to minimise the blowback to the US economy from its sanctions on Russia. That move will go some way to alleviating the pressure on petrol prices, but more is needed, and the Biden administration has also been seeking to ease sanctions on Iran and Venezuela.

Venezuela and Iran are the only two oil producers with significant spare capacity to compensate for the suppression of Russian supplies, if only US sanctions policy would allow.

Over recent years, the US has been seizing oil tankers from Venezuela and Iran on the high seas and auctioning off their contents, with the proceeds going to a fund for US victims of terrorism.

The ‘economic weapon’ hasn’t been used so forcefully against a major power since the 1950s when the Soviet Union was the target of comprehensive US sanctions.

However, both Iran and Venezuela have suffered a similar intensity of international economic blockade and are witness to the failure of what former US president Donald Trump termed ‘maximum pressure’ economic sanctions to achieve their geostrategic objectives. Trump aimed for regime change in both nations but achieved it in neither; in fact, conservative clerics have strengthened their control of Iran.

The capacity of sanctions to cause lasting economic harm to the target is beyond dispute. A study based on a new database of sanctions going back to the 1950s found that comprehensive sanctions destroyed an average of 77% of the bilateral trade between the countries imposing sanctions and their targets.

Moreover, trade takes a long time to recover—an average of eight years—after sanctions have been lifted. When sanctions are lifted, businesses in the countries imposing them remain reticent, while businesses in target countries have become used to exclusion. The study also found evidence of trade weakening ahead of the imposition of sanctions.

The average sanction regime lasts for six years, but there is wide variation. The study (published late last year) found the Arab League had imposed sanctions on Israel for 66 years while the US had maintained sanctions against North Korea for 58 years and Cuba for 54 years. The damage to trade is greater for sanctions that last longer than five years.

In theory, economic sanctions impose hardships on both the elites and the broader public on whom rulers of target countries depend for their legitimacy and, as a result, translate into political pressure for those leaders to abandon their course of action. To have this effect, there must be a clear objective and the targets must believe that the sanctions will be removed if they comply.

In practice, sanctions often become a form of long-lasting punishment short of military action with no clear remedial agenda or timetable for review.

The success or failure of sanctions can be difficult to gauge. The longevity of the communist government in Cuba is often cited as evidence of the failure of US sanctions policy, but the pain that Cuba has suffered may have discouraged other leftist governments in Latin America from expropriating US property.

While sanctions clearly encouraged the military in Myanmar to step back from absolute power in 2011, the threat of them did not stop it seizing power again 10 years later.

It used to be said that the imposition of sanctions on Russia over its annexation of Crimea may not have persuaded it to withdraw, but discouraged further incursions into Ukraine. That is obviously no longer the case: the threat of far-reaching sanctions delivered no restraint to the actions of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Another study using the new database attempts to measure the success of sanctions by comparing their stated goals with determinations by the authorities imposing them on whether they had been achieved. Excluding sanctions that are still in force, it found that 42% of sanction measures fully achieved their goals, while 16% partly achieved their objectives. If sanctions still in force are included, the success rate (full or partial) drops to about 30%.

Since 1950, 44% of sanctions have been intended to defend democracy or promote human rights, while 20% were aimed at preventing or ending war. Over the past 20 years, combatting terrorism and supporting human rights have become more popular goals than preventing and ending war.

The use of sanctions has accelerated over the past 15 years. From 1990 through to 2005, between 200 and 250 sanctions regimes in place around the world, about a third of which were levied by the US. The US share rose to almost 50% under the Trump administration, with the total numbers in force peaking at 550.

Trump was sharply critical of the Middle East wars that followed the 2001 terrorist attacks in the US. In his major foreign policy speech ahead of the 2016 US election, he declared that, unlike other candidates for the presidency, ‘war and aggression will not be my first instinct’. Rather, he said, ‘financial leverage and sanctions can be very, very persuasive, but we need to use them selectively and with total determination’.

The US has increasingly imposed financial sanctions, which ban the use of the US dollar in dealings with a nation, rather than simply embargoing trade. These measures are routinely extended to third parties—a bank from a third country facilitating a trade with a sanctioned nation will itself be banned from transacting in US dollars.

The reason sanctions often fail to achieve their objectives is because the targeted leaders use them to rally nationalist sympathy. And, when economic objectives collide with those of national security, the latter will usually prevail.

This dynamic is clear in Australia. China’s economic coercion of Australia has indeed provoked a change of Australian government policy but not in the direction China may have wished; national security concerns are now paramount in managing the bilateral relationship.

Moreover, economies are flexible: pressure in one part gets compensated elsewhere. If trade is curbed, domestic demand can rise instead. Sanctions on Iran had a severe effect. The economy contracted by 9% over 2018 and 2019, though the ground had largely been made up by 2021. Sanctions mean Iran has had no real growth in purchasing power for the past decade, but everything hasn’t stopped: business continued.

Sanctions, combined with government incompetence, were much more damaging in Venezuela, where the ‘purchasing power’ measure of national output has collapsed 66% since 2016. However, Venezuela’s economy was always more narrowly based and less sophisticated than Iran’s.

Russia’s economy has the size, diversity and sophistication to adjust, although there will be some undoubted hardships and oligarchs will rue the loss of their London pads and Mediterranean yachts.

A larger question is raised by Cornell University’s Nicholas Mulder, the author of a penetrating new history of the use of economic sanctions between the First and Second World Wars. Economic sanctions were employed by the members of the League of Nations in pursuit of internationalist goals: they believed the ‘economic weapon’ as they termed it (and the title of Mulder’s book) could be used to make nationalist wars obsolete.

Instead, they compounded the effects of the Great Depression and fuelled the rise of nationalism in Germany, Italy and Japan, which sought to achieve self-sufficiency to defeat economic embargoes through conquest of supplier nations. ‘Blockade phobia’ was a propelling force towards World War II. Mulder cites Adolf Hitler declaring in 1939: ‘I need Ukraine so they cannot starve us out like in the last war.’

Sanctions designed to discipline nations departing from globally accepted norms may speed the breakdown of global comity rather than prompt its restoration.