Graph of the week: safety in numbers

I liked Phil Radford’s piece on cyber security and the cloud this morning. In particular, I liked the parallel between cyber security and anti-submarine warfare (ASW), having spent a fair chunk of time in Russell Offices doing operations analysis calculations and modelling on the topic.

Phil’s point is that, given a limited amount of defensive resources, there’s a higher degree of safety to be had if targets congregate together behind the defences available than if they take their chances individually. That’s certainly true in ASW, and the effort of researchers to quantify the advantages of convoys is one of the great success stories of operations analysis.

It’s easy enough to describe the potential pros and cons of a convoy system in qualitative terms. Working in favour of grouping ships together to escort them through submarine infested waters is some straightforward geometry: the area of a circle grows like the square of the radius, while the perimeter is simply proportional to the radius. To see why that matters, have a look at the photograph below. Given the same spacing of ships, by doubling the radius of the group, you can get four times as many ships within the defensive perimeter. But the perimeter itself has only doubled—meaning that a defensive escort of warships need only be twice as large to remain equally effective. That’s the good news.

Caption: An aerial view of a convoy in the Atlantic, 1941. Two escorts can be seen in the foreground. (Photograph courtesy IWM)

The bad news working against the convoy is the fact that it’s easier to locate a large group of ships than a single ship in an expanse of the ocean. The question then becomes which factor is the dominant one—can submarines find and attack convoys with greater efficiency than the defenders can protect them?

The answer, both theoretical and observational (based on the brutal results of the Battle of the Atlantic 1940–43), is that the convoying system works. Here are the facts and figures that explain why. (Wonks can find more detail here. Seriously mathematical wonks should track down this book.)

Firstly, the chance of a submarine randomly finding a convoy does increase as the convoy gets larger, as we’d expect. But the increase is modest compared to the number of ships involved. In WWII the most important factors were visual sightings of the ships (or their smoke) and radar contacts, both of which require the submarine to expose part of itself above the surface. Neither of those factors gives a big increase in detection probability—the sighting of smoke for a 64 ship convoy is possible from about 37 km, compared to a little less than 10 km for a single ship. That’s a handy increase (from the submarine’s point of view) but doesn’t offset the huge increase in the number of ships.

These days a submarine would be much more likely to keep its head down and rely on passive sonar; listening for the noise the ships make. Again as we’d expect, a group of ships makes more noise than a single ship and is able to be detected from further away—but not that much further away. A symphonic orchestra of 100 players is louder than a single instrument, but it’s only about four times as loud, not 100. So it is with radiated noise and sonar detection. Because sonar conditions vary enormously, there’s no single number that can be ascribed to the advantages of convoying, but a submarine listening out for sonar contacts will make many fewer detections if the ships are grouped than if they’re well spread out. (Again for the wonks out there, a convoy of 50 similar ships will have a signature about 30 to 35 dB above a single ship.)

Of course, there’s one other important factor. Even if the convoy is harder to locate, once contact is made, it offers a much more ‘target rich environment’ than isolated vessels. We’d expect the losses experienced during an attack to grow with the convoy size—the question is whether those losses outweigh the advantages? Two factors will tend to work against that—firstly, a target rich environment can overwhelm the submarines weapons payload (schools of fish and flocks of birds also work this way) and, of course, the defences can concentrate.

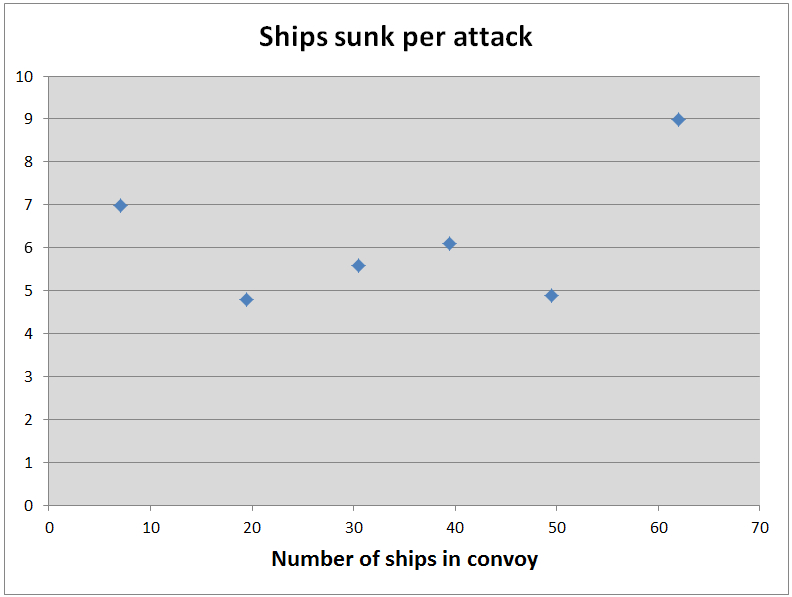

Here’s the WWII data from the Atlantic theatre for 1941–42. The convoying effect is dramatic—there’s very little increase in the loss rate as convoys go from 20 to 65 vessels. (Final wonk alert: the correlation between convoy size and sinkings is only 13%.) In fact, if it wasn’t for the effect of the data for very large convoys, which tended to be slower and take longer to form up (both of which played to the submarine’s advantage), there’d be effectively no extra losses with convoy size.

There’s a lot more to the story of the ASW battles of the past than these simple observations, but the moral of the story is clear—there is safety in numbers, despite larger targets seeming more enticing, and being able to focus defences works. Just how well this translates into the cyber world is an interesting question, but thanks to Phil for this little trip down memory lane!

Andrew Davies is a senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist.