Graph of the week: if you want it on time, keep it simple

Late last year, I gave some early impressions of the Australian National Audit Office’s Major Projects report. Today I’ll have a closer look at some of the data in the report, which will bring us back to another of ‘Gumley’s Laws’. This time the subject is the impact of developmental work on project delivery. (The previous Gumley’s law post was on over-programming in the Defence Capability Plan.)

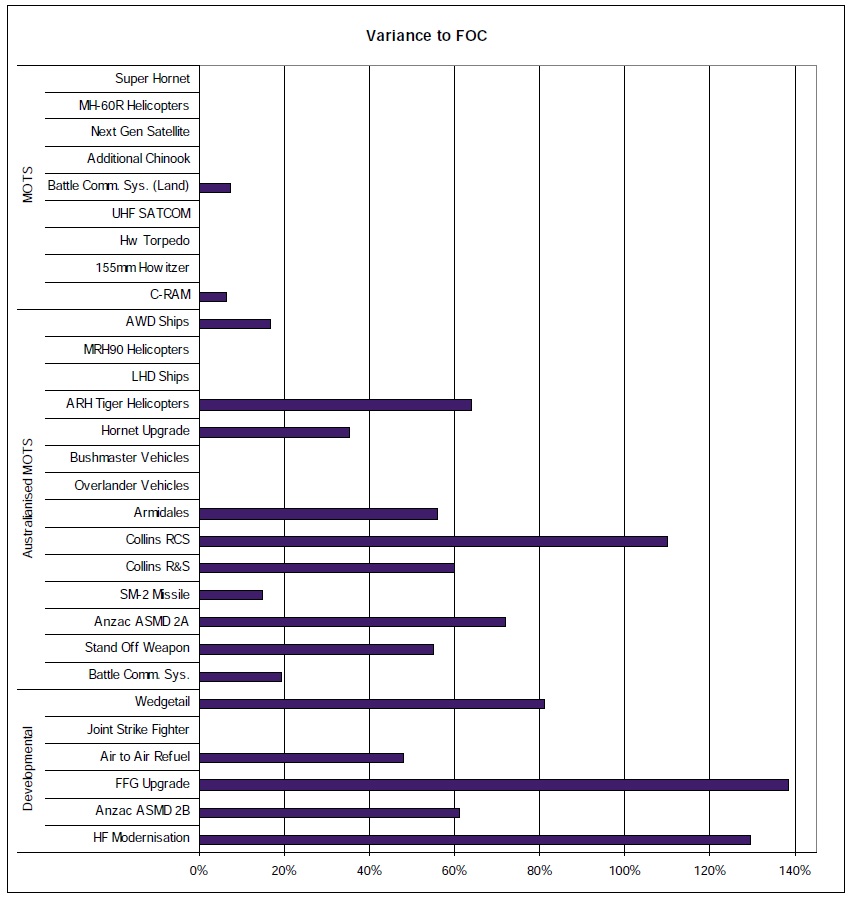

First, the data. The figure below is taken from the ANAO report and is DMO’s breakdown of the delay in projects delivering Final Operating Capability to the ADF. The projects are split into three categories—military off-the-shelf (MOTS), ‘Australianised MOTS’ and ‘developmental’.

The figure is a stark illustration of the penalty paid for developmental work. None of the developmental projects have been delivered without a 40% overrun in schedule, and the average is 92%—almost double the planned time. Note that the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is excluded by the DMO as ‘not applicable’ because it’s ‘should ultimately become MOTS when it enters production line delivery’. But it certainly doesn’t buck the trend—on original plans the RAAF were to have their first operation squadron in 2012, but will now have to wait until 2020.

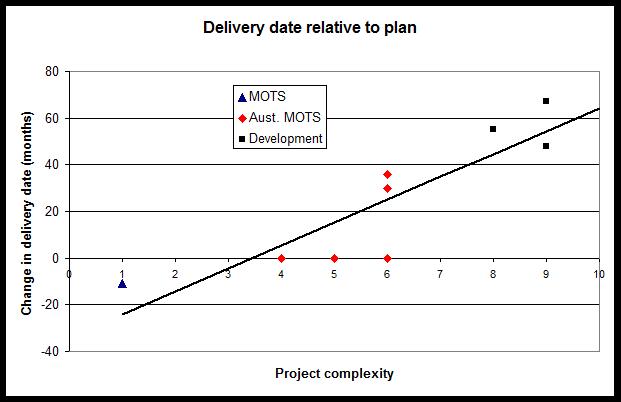

The breakdown into three categories is very coarse, but previous data sets had more fidelity, which allow us to estimate the effect of project complexity on schedule. The figure below is drawn from earlier ANAO reports, when the DMO gave a project complexity figure on a scale from 1 (simplest off-the-shelf) to 10 (most complex integration and development). While the data set is fairly sparse, it suggests the expected delay in project delivery is about 6–10 months per degree of complexity compared to an OTS purchase. And that’s about right when we compare it to the delays in delivering projects like the Collins class submarines and the F-35.

Gumley’s laws include two observations pertinent to this. The first is that:

Off-the-shelf acquisition of products that are technically mature is the only reliable way of avoiding cost and schedule risk. (Gumley’s 1st law)

That rule (which should be self-evident) has a natural corollary that Gumley also identified:

Deviation from MOTS increases risk, cost, and schedule and should only be pursued when there are no MOTS systems with acceptable performance. (Gumley’s corollary to Law 1)

I’d go further than that. If we combine Gumley’s first law with Augustine’s observation that ‘the last 10% of the performance sought generates one-third of the cost and two-thirds of the problems’, I think the corollary should take Augustine into account and read more like this:

Deviation from MOTS increases risk, cost, and schedule and should only be pursued when there are no MOTS systems with performance within 10–20% of that sought and when the extra performance is judged to be critical.

Gumley’s second law is a less obvious, but no less important observation:

Combining two MOTS systems is not MOTS. (Gumley’s 2nd law)

It’s important because it’s much easier to conceive projects that involve taking two separate MOTS components and integrating them —even ones that are themselves mature and fully functional—than it is to deliver them. Some examples from Australia’s experience include the lengthy process of integration of the AGM‑142 missile onto the Royal Australian Air Force’s F‑111 fleet and the much delayed FFG frigate upgrade. In both case all of the subsystems were well-understood, but the interplay between them was anything but straightforward to manage. The FFGs re-entered service years later than expected and the F-111 managed to fire its first AGM-142 just over a year before the airframe was retired. (A quick mea culpa: my fingerprints will be found on that sorry saga.)

Perhaps the most egregious example was the failed attempt to modernise the Super Seasprite helicopter, which required the integration of flight and combat systems, weapons and sensors sourced from multiple suppliers. The net result was a $1.4 billion investment for no capability return at all.

Gumley’s second law also has a corollary:

‘Australianised MOTS’ is an oxymoron.

Or, to put it simply: ‘if you change it, it isn’t MOTS’. Again, the data bears this out. The ‘Australianised MOTS’ projects in the ANAO chart above have an FOC delivery variance of just under 50% above the planned figure—not as bad as the developmental projects, but a long way short of the MOTS projects, for which the average slippage is closer to 2%.

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist.