From the bookshelf: the AIF in Battle

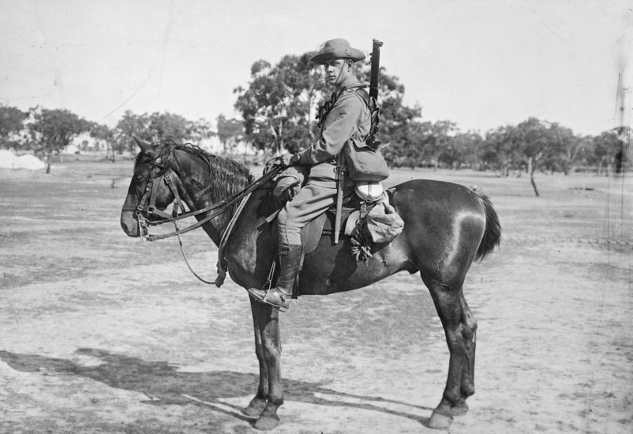

Generations of Australians have been told that the Australian Light Horse Regiments, which distinguished themselves from the Sinai to Syria during the Great War, were not Cavalry. They were Mounted Infantry.

Jean Bou, an historian who teaches at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at ANU, addresses this matter of Australian military history and martial culture early in this fine book of which he’s the editor: The AIF in Battle: How the Australian Imperial Force Fought 1914-1918. His conclusion will surprise some. Bou explains:

‘Writing just a few years after the end of the First World War, Henry Gullett, the official historian of Australia’s involvement in the Palestine Campaign wrote of the Light Horse that they “were mounted riflemen, or in other words, mounted infantry, and their horses were intended merely to give them the greatest range of activity as a mobile body.” This brief passage … has proven remarkably durable.’

The major difference between mounted infantry and cavalry of the day was equipping the troops with sword or lance for deployment as shock troops at the charge. At Beersheba, the Light Horse did charge, of course, but the bayonet was the offensive weapon.

Pursuing Ottoman forces into Palestine, the commander of the Australian Mounted Division, Britisher Major-General Henry Hodgson, advocated issuing swords to his troops. Appreciating the success of Indian cavalry with the lance in early 1918, the Desert Mounted Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Harry Chauvel, agreed. Several brigades of the Light Horse then became cavalry, sweeping the enemy back into Syria and contributing substantially to Allenby’s victories.

This is a deceptively impressive book: seemingly far too brief for its aspirations in covering the AIF in European and Middle Eastern theatres, on land and in the air. But Bou’s ambitious editing has crafted a comprehensive guide to the First AIF in the cauldrons of battle, as it struggled to transform from a militia into a force capable of waging war on an industrial scale. And while The AIF in Battle is written primarily for an academic constituency, it repays reading by a far wider audience of those interested in the evolution of Australian arms from 1914-18.

Let’s be clear: from Gallipoli through Pozieres to Mont St Quentin, the soldiers of the First AIF set a standard which is still there to challenge our fighting men and women today. That the First AIF distinguished itself in battle’s not in doubt. The performance of the Australian Corps in 1918 on the Western Front, alone, is testament to the crack nature of our troops.

But Bou and his collaborators range across the vast landscape of the Great War, examining in detail the differing contributions of Australian warriors—from artillery to the air; trench raiding or mining operations; unit structures to the emerging Australian commanders—in a comprehensive assessment of the growth of the Australian military as well: its strengths and weakness and its ultimate battlefront success.

Some stories are already threads in the fabric of our military history. Others such as Aaron Pegram’s account of trench raiding to instil aggression and maintain tactical agility throw new light on Australian small unit discipline in the frustrating and dangerous static warfare of the Western Front.

Similarly, the origins of close air support are discerned in Michael Molkentin’s chapter, ‘Over the Western Front: Air Power and the AIF’, as the emergence of the Australian Flying Corps, under the command of the Royal Flying Corps, made its presence felt in photographic reconnaissance; close support for Allied armies and as an instrument of strategic destruction. Like Britain’s other dominions, Australia supplied air crew in significant numbers, as we were to do again in 1939-45. A high price was paid for empire loyalty and commitment.

Molkentin notes: ‘The dominions made a notable contribution to the empire’s effort in the air, with at least one in five of those killed in Britain’s flying services hailing from British settler societies.’

David Horner’s chapter on the Australian commanders is among the best. The pre-war reliance on a defence based primarily on militia units was soon demonstrated to be completely inadequate in modern warfare, something the Americans had learned in the war of 1812. Hard lessons were learned from Gallipoli to Fromelles to Bullecourt. The carnage earned widespread dissatisfaction with a British High Command apparently indifferent to casualty lists.

Pressure from William Morris Hughes’ government saw more Australian commanders promoted and names such as John Monash, Talbot Hobbs, Charles Rosenthal, and John Gellibrand were at last acknowledged in reports as they assumed higher command posts.

Horner’s final assessment is instructive: ‘The existence of a multitude of competent Australian commanders by 1918 was an outcome that could only have been dreamed about when the AIF had been formed four years earlier. With this reservoir of expertise the 2nd AIF in the Second World War was led by experienced Australian commanders from the first day. Few of them had to learn their trade on the job.’

Unquestionably true and extraordinarily valuable in the defence of Australia a generation later, this truth underlines the cultural significance of the First AIF in the creation of an Australian defence doctrine that endures to the present. Bou and his colleagues are to be commended for an incisive analysis of the First AIF and its finest hours on the battlefield.