From the bookshelf: ‘In the dragon’s shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese century’

Southeast Asia is a region of crucial strategic importance to China. The Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea are choke points for much of its international trade. The mainland states of Southeast Asia have been closely connected with China for centuries. And Southeast Asia is one area on its periphery where China is not encircled by another great power.

With the rise of China as an economic and political power in recent decades, Southeast Asia has become a critical economic partner for China, as well as a target for China’s political influence, as well documented by Sebastian Strangio in his recent book, In the dragon’s shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese century.

Strangio began his career as a reporter at the Phnom Penh Post in Cambodia, and has since traveled and reported extensively across the 10 nations of ASEAN.

With some flair, he weaves stories of the rich history of the region, with a discussion of recent trends and defining issues. Recurrent themes through his country profiles are mutually beneficial economic cooperation, Chinese attempts at regional domination, pushback by regional countries and the waning influence of the US.

Nowhere in the world is China’s rise more visible than in Southeast Asia, according to Strangio, due to the reality of proximity. For centuries, they were bound together by trade, tribute, movements of people, and cultural and technological diffusion. And with China’s economic renaissance, China and Southeast Asia are now tied ever more tightly together, thanks to a ‘collapse of the distance’ between the two. A network of highways, rail lines and special economic zones is breaking natural barriers with mainland Southeast Asia. And there’s a similar collapsing of distance at sea as China has built-up a world class navy.

Southeast Asia is also home to sea lanes which are critical for China’s booming trade, especially imports of crude oil. This is the basic strategic driver of China’s occupation of the South China Sea, writes Strangio, rather than claims of historic rights and traditional fishing grounds.

For Southeast Asia, China’s proximity has always been a mixed blessing. The lure of prosperity coexists with fear and trepidation about what a powerful China will mean for the region’s future, especially in light of the deterioration in US–China relations. In some countries, it has reawakened memories of China’s support for communist insurgencies during the Cold War and the vexed question of its relationship with the region’s ethnic Chinese communities, according to Strangio. And China has mirrored its construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea by damming the upper Mekong River, giving Chinese dam engineers the power of life and death over large swathes of the downstream Mekong nations.

China is not popular in Southeast Asia, and is its own worst enemy with its imperious attitude, writes Strangio. The general Chinese message to the region is that it can flourish within a Chinese orbit or languish outside. In short, China believes that Southeast Asian states should defer to its wishes. While all great powers tend to behave that way (‘great state autism’), in China’s case it may be worse as it also reflects the nature of its one-party, authoritarian system that leaves very little space for civil society. One disturbing trend has been Chinese outreach to the ethnic Chinese populations in Southeast Asia to enlist their support, which risks reawakening old fears about dual loyalties on the part of ethnic Chinese, notably in countries like Indonesia.

Nevertheless, a prosperous and stable China is in the best interests of Southeast Asia, which has good reason to maintain healthy relations with its big neighbour. China has become a vital economic partner to every nation in the region, and has been more helpful than the US for dealing with Covid-19. Despite the risks and challenges of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, it is very attractive to the region’s poorer countries for kickstarting their economies. The reality of geographic proximity makes China something that Southeast Asia can’t ignore or wish away.

Thus, despite their immense goodwill towards the US, Southeast Asians are reluctant to sign up to any American-led alliance or coalition of states aimed at containing China’s power. Indeed, many Southeast Asians are concerned that the US often sees its relationship with the region mainly through the prism of its great-power competition with China. The depiction of the US–China competition as an all-or-nothing struggle between democracy and dictatorship has failed to gain much traction in Southeast Asia, argues Strangio.

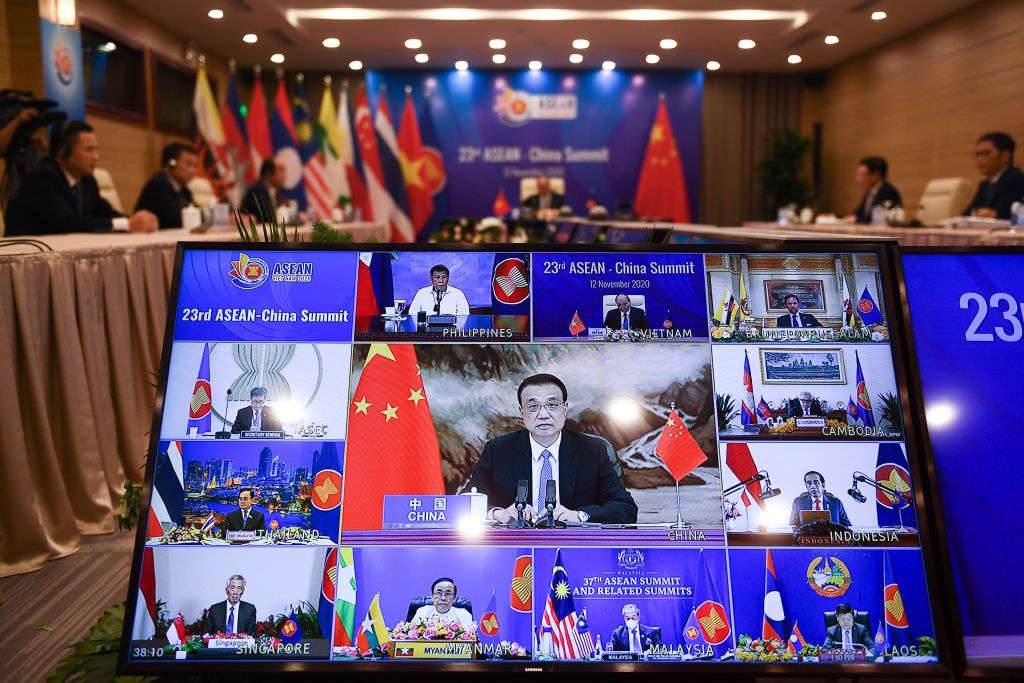

In this informative and readable book, Strangio concludes that the emergence of a more powerful and belligerent China poses the most serious foreign policy challenge that the Southeast Asian region has faced in a generation. One issue that could have been developed further is the future of ‘ASEAN centrality’—the notion that regional security and economic cooperation revolve around ASEAN.

In reality, ASEAN now seems less effective and cohesive than ever. It is being fractured by China’s adoption of Cambodia as a client state. Mainland ASEAN states are becoming more economically integrated with China than with other ASEAN states, and are thus drifting away. ASEAN’s perennial weak point, its inability to solve problems in its own backyard, has been highlighted once again by the political crisis in Myanmar. And ASEAN’s biggest member Indonesia is clearly more preoccupied with national interests and demonstrates very little regional leadership.