From the bookshelf: An Australian diplomat who loved the Arab world

The Arab world ‘has too much history and not enough geography’.

Savour that vivid phrase as the essence of Bob Bowker’s fine memoir of life as an Australian entranced by a Middle East that is crammed full of ‘memories and mythologies’.

Bowker is the ‘dean’ of an exceptional group of Australian diplomats who dedicated their careers to understanding the region. The dean description is from Nick Warner, a Canberra wise owl of foreign policy, defence and intelligence, who says Bowker throws much light ‘on the history of our relationship with the Middle East, where we have gone wrong and right, and what we should do now’.

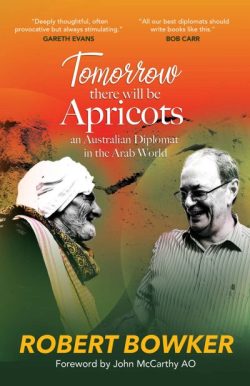

The book title gives a taste, in several senses: Tomorrow there will be apricots: an Australian diplomat in the Arab world. Bowker explains that the apricot prophecy is a Syrian saying similar to the scoffing English expression, ‘Pigs might fly.’

The hope for apricots, he writes, ‘captures an unquenchable, droll optimism which, together with the deep appreciation of culture and hospitality, ranks highly among the virtues that define what it means to be Arab. It also reflects an abiding scepticism towards the pretensions of those in positions of authority.’

Bowker offers a two-part book in 300 pages. The first half traces his career as a Middle East specialist in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which he joined as a diplomatic cadet in 1971. The second part, titled ‘Reflections’, is an analysis of the big issues confronting the region.

The two-in-one package offers a fine blend of the personal and the policy, describing a near-50-year journey: 37 years with DFAT and then 12 years as an intelligence analyst with the Office of National Assessments and an academic at the Australian National University.

‘Being an Australian diplomat in the Arab world was more than a career: it was an adventure,’ Bowker writes. ‘In many ways it was my life.’

He notes how former prime minister John Howard labelled himself a cricket ‘tragic’ because he was tragically in love with cricket. Bowker embraces the hopelessly-in-love thought, titling the first half of the book ‘The career of a Middle East tragic’. It’s notable that the book starts with that light-hearted reference to Howard, because one of the great policy fights of Bowker’s career was Howard’s shifting of Australian policy on Palestinian self-determination to lean towards Israel. The diplomat notes he was ‘trumped by the Prime Minister’ and ‘went down in flames’.

A great scene in this flameout has Bowker locked in a shouting match with the prime minister’s foreign policy adviser at the annual conference of the Zionist Federation. Howard was sitting only metres away, preparing to address the conference dinner.

The breach is an example of Bowker’s observation that the policy choices the Middle East has to live with are between bad and much worse.

Tragically in love with the Middle East in all its tragic complications, Bowker offers great yarns, finely told. He has an ear for the telling quote and the eye for a good scene.

Heading off for his first overseas post as a third secretary, only seven months after joining the department, he records the three pieces of advice given him in the conversation that amounted to his consular ‘training’: ‘Never take possession of a corpse. Never take possession of a mad woman. Use your common sense. And that was it.’

At his second post in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, his struggle learning Arabic is illustrated by his regular visit to a roadside stall: ‘I later realised that when I thought I was asking, in terrible Arabic, for a freshly cooked chicken, I was actually asking for a fresh wife. The stall owner didn’t seem to mind.’

Bowker’s ‘colloquial Levantine Arabic’ had many uses beyond talking to taxi drivers. To impose some ceremonial pain on Sudan’s president for atrocities by his tribal proxies in Darfur, the ambassador gave ‘my speech on presentation of my credentials in Arabic’.

In a gem of a chapter titled ‘Touring Tobruk by moonlight’, Bowker captures Libya’s ‘blend of chaos and impenetrability under the Ghaddafi regime’ by describing his scouting trip, as the non-resident ambassador, for a prospective visit by the Australian defence minister to a war cemetery.

Two Libyan minders drive him from Benghazi in a car that ‘sounded very sick indeed’ to tour a range of war cemeteries—British, French and German—but can’t find the Australian site until the moon is out. At the end, the minders have an animated discussion about the report they must file ‘on why the ambassador chap had been scoping out the port area and surrounds of Tobruk, especially the high ground overlooking the harbour, quizzing the local about the layout of the urban area, and doing so in execrable Arabic’.

When they got back to Benghazi at 0130, one of the minders ‘shook my hands and planted kisses on both my cheeks. When you are kissed by a Libyan security official, you know it is time to go home.’

Writing of his time in Syria in the 1970s, Bowker recounts a local quip: ‘Saudi Arabia exports oil, Iraq exports dates, Egypt exports jokes and Syria exports trouble.’ The three-line description of then-president Hafez al-Assad is a miniature masterpiece of disdain: ‘His smile was like moonlight on a tombstone’; Assad had a ‘penchant for delivering historical lectures’ and dominated meetings with ‘his awe-inspiring bladder control’.

Bowker’s sad conclusion is that the Assad family—Hafez and now his son Bashar—has become a regime that outlasted the country. The bedrock of Bashar’s rule is its brutality, he writes, and father and son always avoided ‘questions about the appropriate relationship in Syria between state and society’.

In his reflections, Bowker considers the department that made his career, lamenting how the role of Australia’s diplomats in Canberra has changed, ‘and not for the better’.

DFAT, he argues, gives priority to trade and consular crisis management ahead of the research and thinking needed for effective foreign policy planning and advocacy. Policy is ‘created in ministerial offices, with DFAT seen more as an implementing agency for those outcomes. This is a deeply problematic direction for any government, or government department, to take.’

DFAT no longer debates with itself and the rest of Canberra through dispatches and cables: ‘The final decade or two of my time in the department saw a shift to reporting by cable that was prone to be concise rather than nuanced. It was directed in its brevity towards immediate briefing needs, rather than the evaluation of trends and their consequences for Australian interests.’ Under the Howard government, he notes, the lengthy dispatch from a post became a thing of the past: ‘By the time I retired it had become almost unthinkable to reflect on broader issues, let along to challenge policy settings, in cable traffic.’

Bowker tackles three core questions in his reflections:

1. ‘How do you build peace between two peoples—Israelis and Palestinians—with compelling national rights, human rights and historical narratives, but who have a clear imbalance of power?’

2. How does one connect the present, the past and the politics of Palestinian identity? This is an intellectual who 20 years ago wrote the book Palestinian refugees: mythology, identity and the search for peace. As a diplomat, he offers the answer (‘if there is one’) of negotiating on interests, because beliefs are ‘organic, structural and fundamentally non-negotiable’.

3. How does the Arab world confront its demographic fate (a Middle East population of 724 million people by 2050) and its economic and social challenges while preserving its Arab and Islamic identity? ‘None of the current leaderships of the major Arab states and Iran have answers to the problems of legitimacy and governance,’ Bowker writes. His fear is that governments will ‘grow more authoritarian, transactional and violent in their instincts and behaviour’. Defending privilege and predictability, rulers have found that repression works for them, arguing that ‘freedom is more likely to produce chaos and division rather than bread and social justice’.

The Arab outlook, Bowker observes, feels like being on the bridge of the Titanic smelling the ice. It took the Titanic a long time to sink, though, and the modern Arab world has no way to stop the drivers of change, which are ‘generational and societal as well as political’.

On the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Bowker declares that the two-state approach pursued since the 1990s ‘is dead’. He pointedly calls it a two-state ‘approach’ because no solution is in sight.

If the two-state approach is mired in fundamental conundrum, he argues, the path to justice is by ‘building a foundation for Palestinian rights and dignity among Israelis’.

Israel can facilitate a new, more positive future for Palestinians and Israelis, he says, without raising existential questions for Israel: ‘The absence of sovereignty is a legitimate grievance for Palestinians, but in practice it is the absence of dignity and economic security that matter much more.’

If the two-state option is dead, as Bowker avers, then Palestine’s dream of independence must fade. As The Economist wrote recently, the Palestinian diaspora has ‘begun to call for a one-state solution, where Jews and Arabs between the Jordan rivers and the Mediterranean would live together in a single democratic state—and where Arabs would have a slender overall majority’.

For Israel and the Arab world, demography should meet democracy, and history must reconcile with geography.

In a piece for The Strategist two years ago, Bowker wrote that ‘the convenient fable of a two-state solution’ has to be challenged: ‘A one-state approach would require mobilising political support for a fundamental rearticulation of the political, security and social apparatus and identity of Israel.’

Bowker concludes that the fun and frustrations of his life as a Middle East tragic have forced acceptance of key realities.

Middle East policy is not a morality play, he writes. Expediency shapes decisions: ‘The logic of strategy is not always consistent with the logic of politics.’

Diabolic complexity rules. The nature of the Middle East is for problems to linger and become more complex, Bowker writes: ‘We must accept that views, interests and values within Arab societies are more likely to differ from our own: any apparent synchronicity of views should be cause for caution, as well as celebration.’

The final sentence of this tragic’s meditation on his life’s works reads: ‘And, despite almost 50 years of exposure to the Arab world, I remained free of tribal delusions, except where Collingwood is concerned.’

Ah, the Melbourne conundrum of the Collingwood Football Club—the one passion running through this fine book that (in the tribal view of this reviewer) does not bend towards truth and logic.