Decision to bring China’s military into the South Pacific in the hands of Solomon Islands PM

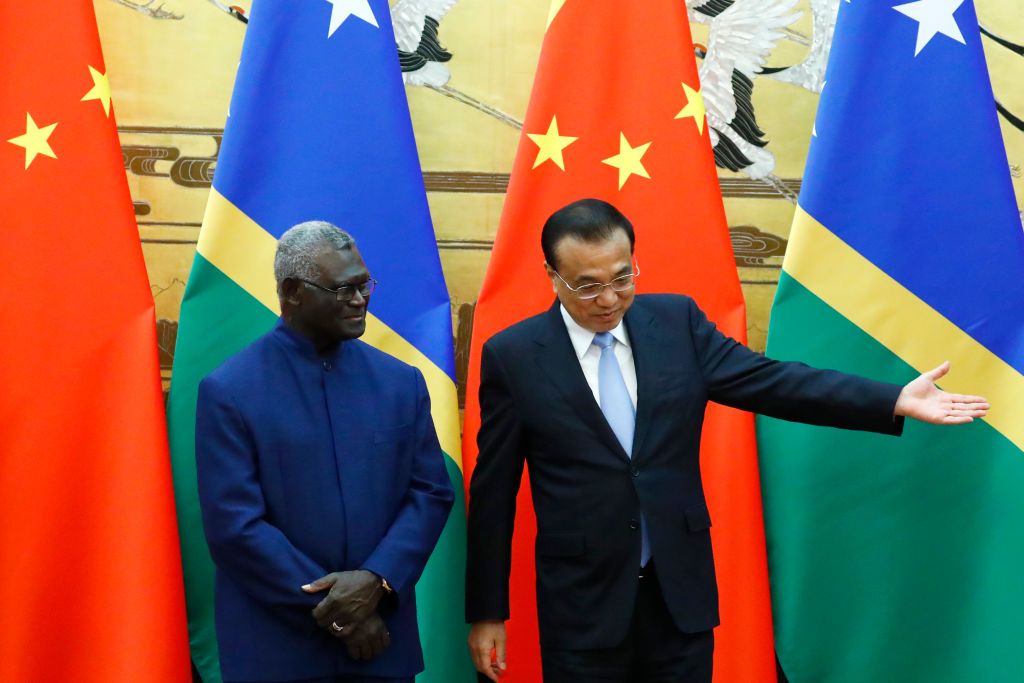

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare has a Chinese-government-proposed text for a security agreement between his country and China, which is apparently being considered by his government.

The draft agreement leaked to the media is a short, broad document with some specifics about a process for the Solomons to request Chinese police, armed police and People’s Liberation Army assistance to deal with unrest. That’s a disturbing picture, given the authoritarian nature of Chinese enforcement functions like the oddly named People’s Armed Police and the brutal work we’ve seen the Chinese police, paramilitary and military do on the streets of Hong Kong, in Xinjiang and in Tiananmen Square.

But the bigger issue for every person in every one of the 18 member nations of the Pacific Islands Forum is the other bit of the draft agreement, which says:

China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of the Solomon Islands, make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands, and the relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in the Solomon Islands.

That’s a very broad, loose set of permissions for Xi Jinping to use his forces to operate in and from Solomon Islands. And it’s straight from the Beijing playbook: create new forms of activity and then normalise and increase them in accordance with Chinese interests.

A core issue is that South Pacific leaders have been hoping that strategic competition wouldn’t come to them in any way other than a contest to give them things. And we’ve had statements from leaders like former Vanuatuan foreign minister Ralph Regenvanu showing this sentiment: Chinese interest is good for us because it means we get better offers from our other partners.

Like Australians until the Huawei 5G decision back in 2018 and some business figures even now, some have been happy to take Chinese cash and downplay the downsides, particularly if they’re longer term and the benefits are more immediate.

But the prospect of a routine Chinese navy and army presence in Solomon Islands shows that this transactionally savvy approach to get better deals is coming to an end, and the nasty end of direct military and strategic competition—tension and perhaps even conflict—is coming in the form of Chinese power, which will no doubt be opposed by Australia and its allies and partners in the South Pacific.

Australia’s task now is to support those who already see these implications—like Solomon Islands opposition leader Matthew Wale and other figures across the Pacific, along with voices in Honiara calling for greater honesty and openness in government like Reginald Ngati.

It also means shifting the views of those who still think the possibility of a standing PLA military presence in the region is scaremongering by Australia or others. I’m certain plenty of voices in the Solomons and other Pacific states understand this, even if particular leaders like Sogavare know but don’t care because of other priorities (in an echo of Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews on the Belt and Road Initiative saying he wasn’t responsible for national security or foreign policy, just jobs in his state).

Would a new treaty signed by Pacific states committing to no such military presence by China or other authoritarian powers help? Probably not. The Pacific Islands Forum’s Boe Declaration already commits to a region of ‘peace, harmony, security, social inclusion and prosperity so that all Pacific people can lead free, healthy and productive lives’ and rejects foreign interference. Providing a place for China’s military to project power from inside the region would certainly clash with these principles.

And as we know with space and cyber treaties, the simple fact is that two kinds of states sign these agreements: ones that do what they sign up to—like the Pacific Islands Forum states and partners like the UK, US, France and New Zealand—and those, like Russia, China and North Korea, that sign hoping others feel bound while happily breaking any obligations themselves, just as Xi did when he tore up his obligations under the Sino-UK treaty on Hong Kong with his brutal crackdown in 2019.

It’s understandable for South Pacific governments, businesses and people to welcome economic and even political competition, including from China. However, the draft agreement’s clause on ship replenishment and logistics support ‘according to China’s needs’ would bring a very different type of competition—real military competition—into the heart of the South Pacific.

It is not in the interests of South Pacific peoples to have the region become a place of military competition, tension and conflict. Even if some leaders don’t want to act on this, other voices should be listened to. And Australia’s job is to speak frankly and keep our word, to show that we are part of the Pacific family and are as deeply against our region becoming a place of actual military tension as any of our Pacific partners are.

Let’s think through events like the targeting with a military-grade laser of an Australian P-8A Poseidon aircraft by a PLA Navy guided-missile destroyer on its way to Tonga just weeks ago. This type of event would become routine behaviour and interaction in the South Pacific.

The single biggest factor that can either bring this reality into being or prevent it is whether the Chinese military is given permission by any government in our region to establish places to base and operate from.

The bad news is that China’s economic leverage can make it hard for a small state to refuse. Australia has had a hard time shifting from our decades-long, wilfully blind dash for Chinese cash, and has only done so grudgingly in recent years as the security implications of an aggressive China under Xi became too obvious to ignore.

The good news here is that, short of a war like Vladimir Putin’s in Ukraine, China can’t unilaterally impose a standing military presence in our region. Such a move would require an active choice by one of our Pacific partners—a choice any government should make not in isolation but by listening to its own people and to every other member of the Pacific family.

If, after careful consideration of all angles around this draft agreement, Sogavare’s government decides not to invite an authoritarian state to establish an armed presence in Solomon Islands, we should remain alert but not alarmed.